Reaching Through B.A.R.S. to Build Better Lives

Posted on July 29, 2021

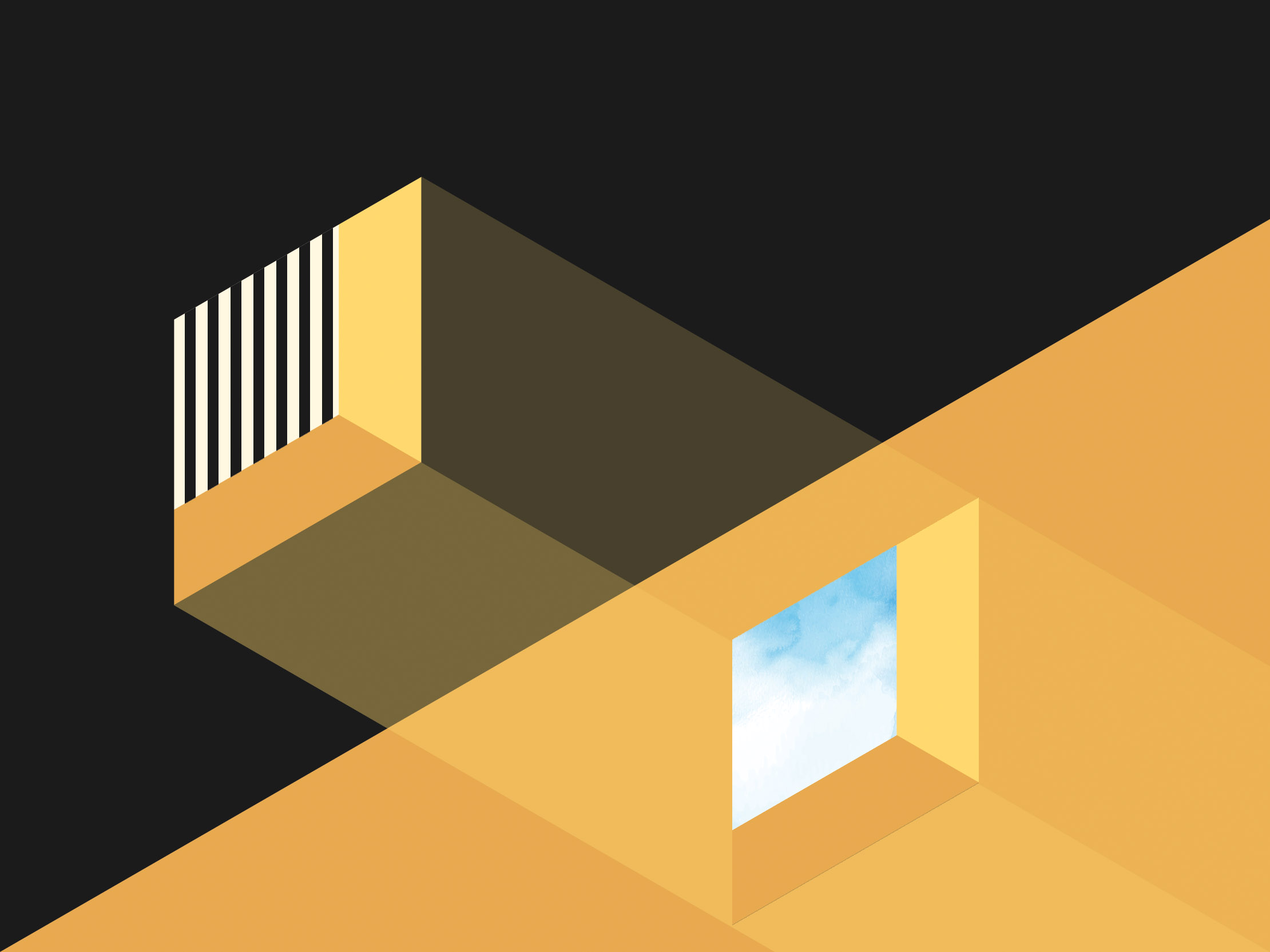

B4’s volunteers helped residents see a life beyond detention, such as visiting the UNC campus and creating plans for when they were released.

Gratitude prompted Mike O’Key to share an experience other people might hide. As a kid — 11 years old, going into seventh grade — he was incarcerated, spending a lot of time isolated in a cell with bars on the window at the C.A. Dillon Youth Development Center in Butner.

But once every week or two, a group of UNC students would come in, bringing snacks, playing games, teaching the residents about Black history and skills such as how to balance a checkbook and interview for a job. The students tried to get the residents to believe that getting caught up in the juvenile justice system did not mean they had to stop moving forward with their lives. As Black men who had faced racism and other barriers, the mentors told the residents in various ways: “This is what I’ve been through. This is how I handled it. You can do it, too.”

The mentors were volunteers from UNC’s B4 — Building Bonds, Breaking B.A.R.S. (Barriers Against Reaching Success) — founded in 2008 and aimed at interrupting the school-to-prison pipeline. Rey Cosmos ’12, Jeremy Martin ’14 (MSA), Javonie Hodge ’12 and Dr. Bo Chigozie Nebolisa ’13 spent a year jumping through the necessary hoops to turn their club into a recognized Carolina student organization, finding an entree into the juvenile justice system and learning not just the institution’s rules but how to truly mentor.

“They weren’t in a hurry,” said Sandra Browning McKeown, then the clinical chaplain at Dillon, who helped the mentors get access to the facility. “There was a sense of ‘this is important and urgent, but it’s important enough to get it right.’ ”

They crafted a detailed proposal outlining their short-term plans and how the organization would survive after their own graduations.

“It wasn’t about egos, about ‘watch us do something great,’ ” Browning McKeown said. “It was about finding a way to make an ongoing difference in the lives of young Black men.”

The most important thing they did was show up, without fail.

“They made us feel seen when everyone else turned their backs on us,” O’Key said.

“A big responsibility”

The mentors built a curriculum that focused on African American history, hoping to instill not just knowledge but also pride in the residents, and in spring 2010, they walked into the prison-like facility. They unfolded chairs in the facility’s chapel and placed them in a circle. They sat and waited as residents, dressed uniformly in khakis and flip-flops, were brought in one at a time.

The UNC students taught about slavery, emancipation, Jim Crow and the civil rights and Black power movements. They broke into smaller groups for animated conversations that tied that history to what was happening at the time.

“They made us feel seen when everyone else turned their backs on us.”

—Mike O’Key

But that was only part of the work. The mentors also organized book drives, trying to reinforce the importance of education and to build the facility’s library. They recruited more volunteers, including future leadership — a particular challenge: Going into a youth prison can be too intimidating for some, Cosmos said.

“Also, just the work of being a mentor is a big responsibility,” Cosmos said. “Consistency is key when you’re trying to be a mentor, especially to incarcerated youth who’ve already dealt with a lot of people coming in and out of their lives.”

B4’s core volunteers became so trusted that they were allowed to take a van full of Dillon residents to UNC’s campus and to the International Civil Rights Center & Museum in Greensboro.

“That was my first time on any college campus,” O’Key said. “It was them saying, ‘This is very much your space, too,’ and I’d never heard that message, that this was an option.”

The B4 mentors created folders of resources and next steps for each resident released. They gave out their personal contact information and wrote letters of reference.

“We got to know the kids, and we got to know their stories,” Cosmos said. “A lot of them either grew up in a single-parent household or didn’t grow up with their parents at all. I think they could tell that we genuinely wanted to be there with them. They could feel the love that we had for them.”

“An act of solidarity”

The Dillon facility closed gradually — Browning McKeown left in 2015 — and its operations shifted to the Edgecombe Youth Development Center in Rocky Mount, much farther from Chapel Hill, so B4 moved its efforts to the Durham County Youth Home.

B4 now has female mentors as well, since women are allowed into the Durham facility. Its most recent co-presidents, senior Brit Burns and Landon Bost ’21, continued to grow B4, looking for ways to reach vulnerable young people who had not become entangled in the system. Unable to visit the facility during the pandemic, they have refined the curriculum as they wait.

“It’s such a privilege just to be able to go to college and do things we might take for granted,” Bost said. “Once you get into that system, the school-to-prison pipeline, it’s hard to get out.”

Once every week or two, a group of UNC students would come in to the youth detention center, bringing snacks, playing games, teaching the residents about Black history and skills such as how to balance a checkbook and interview for a job. The students tried to get the residents to believe that getting caught up in the juvenile justice system did not mean they had to stop moving forward with their lives. As Black men who had faced racism and other barriers, the mentors told the residents in various ways: “This is what I’ve been through. This is how I handled it. You can do it, too.”

Joseph Jordan is director of UNC’s Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History, where the program is based, and faculty adviser for B4. He said that while the mentors are trying to have an impact on the youth, the experience is important for the mentors, too.

“They don’t see this as a charitable engagement,” Jordan said. “They see it as an act of solidarity with the communities they came from.”

The mentors often are only a few years older than the residents. They come from small towns and big cities. They’ve had friends or family members who were incarcerated. They know that slight changes in their own circumstances might have made all the difference in their options.

“I always knew that a lot of times the environment is a big factor to how someone will grow up,” Bost said. “Some people, instead of being empathetic to people who had harder challenges growing up, put the blame on them. We’re just being empathetic.”

Their empathy, age and race have mattered.

“When it comes from somebody closer to the kids’ age teaching and showing them stuff, they respond differently,” said Mario Clark, detention counselor supervisor at the Durham facility. “They’re more attentive, more enthusiastic to get into it.”

The benefits of B4

There are no data to measure the program’s value to either the mentors or former residents, but there are examples of achievement.

Among the early mentors, Cosmos is an artist in Arizona; Martin is pursuing a doctorate in politics and policy at the University of California-Berkeley; Hodge is in finance; and Nebolisa (who also earned his master’s in public health in 2017 and his medical degree in 2018, both from Carolina) is a doctor.

O’Key was released from Dillon when he was in 10th grade and finished high school. He earned dual bachelor’s degrees in environmental design and public administration from Auburn University in 2019 and a master’s in city and regional planning from Cornell University this year. He serves on the N.C. Governor’s Crime Commission’s Juvenile Justice Planning Committee and is participating in research at UNC about how to improve the juvenile justice system.

O’Key said he’d like to use his experience at the federal level, maybe with Housing and Urban Development or the Department of Education. He’s headed to a doctoral program at Stanford to continue studying urban planning, focusing on school district boundaries. He had been admitted to UNC’s doctoral program but said he wanted to keep challenging himself in a new place.

“When I step back, I see myself on this trajectory to be this really cool changemaker in North Carolina,” he said. “But it feels a little bit siloed when the issues that I care about happen on a national scale. Going to Stanford keeps me from being siloed, but it doesn’t close the door on North Carolina. I can easily go to Stanford and come back to North Carolina.”

— Janine Latus

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.