Reading Between — and Along — the Lines

Posted on April 29, 2020

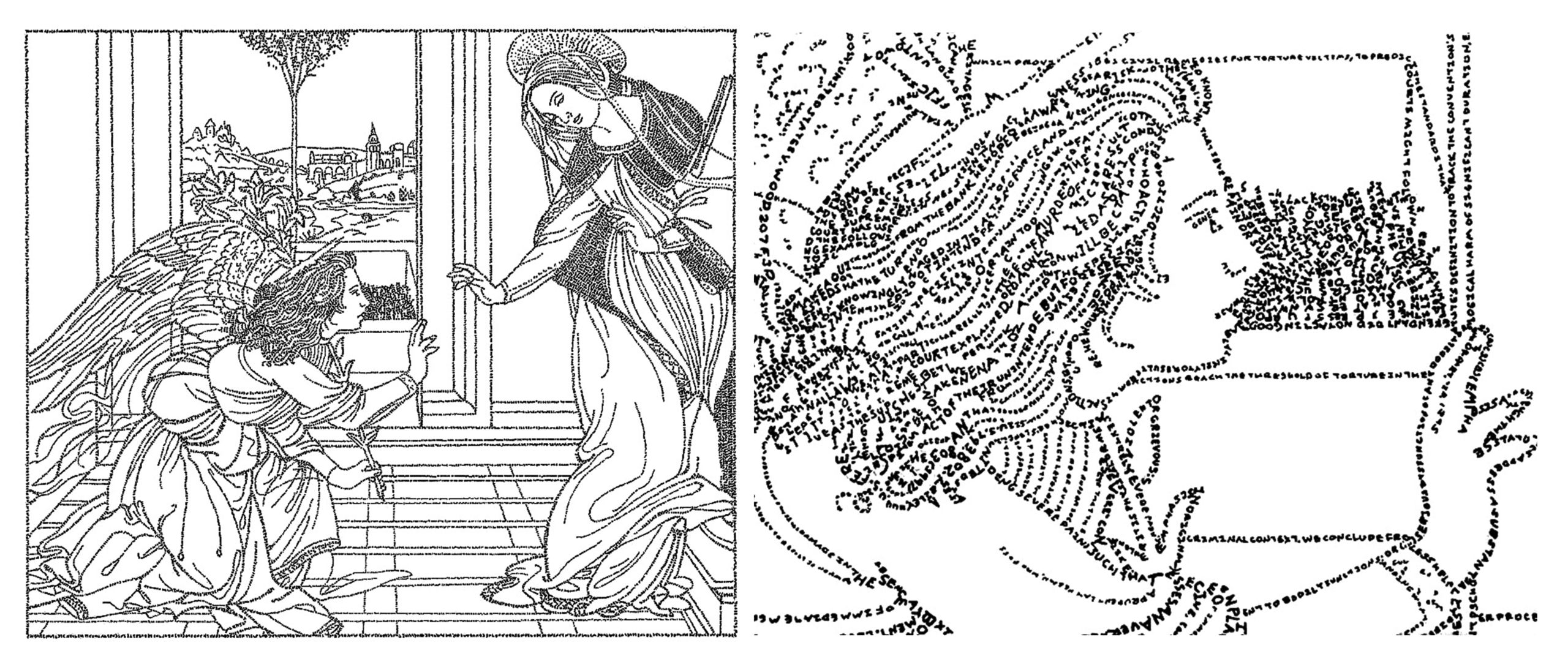

Michael Klauke ’86 (BFA) contrasts images and the tiny words that create them. In Good Faith was inspired by Botticelli’s Cestello Annunciation, the archangel Gabriel telling Mary about the coming Christ child; the words come from legal memos on ways to justify torture of terrorism suspects.

Michael Klauke ’86 (BFA) is a visual artist. But his fascination — and his artistic expression — is with words.

Glance at Klauke’s In Good Faith, and it appears to be a line drawing of Botticelli’s Cestello Annunciation — depicting Gabriel’s revelation of the coming Christ child to Mary, who responded: Yes, may it be done.

Michael Klauke ’86 (BFA)

But look closer.

Those lines actually are tiny words, and the words are ugly — taken from legal memos to President George W. Bush in 2002 on ways to justify torture. Yes, it may be done.

Klauke is fascinated by the contradictions that accompany a phrase such as “in good faith,” the divergent ways that words are interpreted and manipulated. He employs a technique called textual pointillism — images made from thousands of words — for visual renderings of his musings on those contradictions.

Most of his works are familiar portraits or cultural images, with a new context — sometimes complementary, often contradictory.

“I pick people or subjects that I find interesting,” Klauke says. As for selecting the text, “in a lot of ways it’s intuitive. Just something that jumps out at me or catches my imagination. Usually I want it to relate to the subject, but in some, I want it to be counter to the image.”

His inspiration for using text for images sprang from trauma.

“When the 9/11 attacks occurred, a local gallery asked several artists around town to do what they called a reaction to the event, and I really wanted to do something positive,” the Cary resident recalls. “I did a drawing called Beyond Words, with the word ‘GOD’ in big block letters. The G was the word ‘Judaism’ written hundreds of times, the O was ‘Christianity’ and the D said ‘Islam.’ I was trying to do something that would bring people together.

“I looked at it, and I thought, ‘Wow! If I can make a big word out of a bunch of little words, maybe I can make images out of a bunch of little words.’ ”

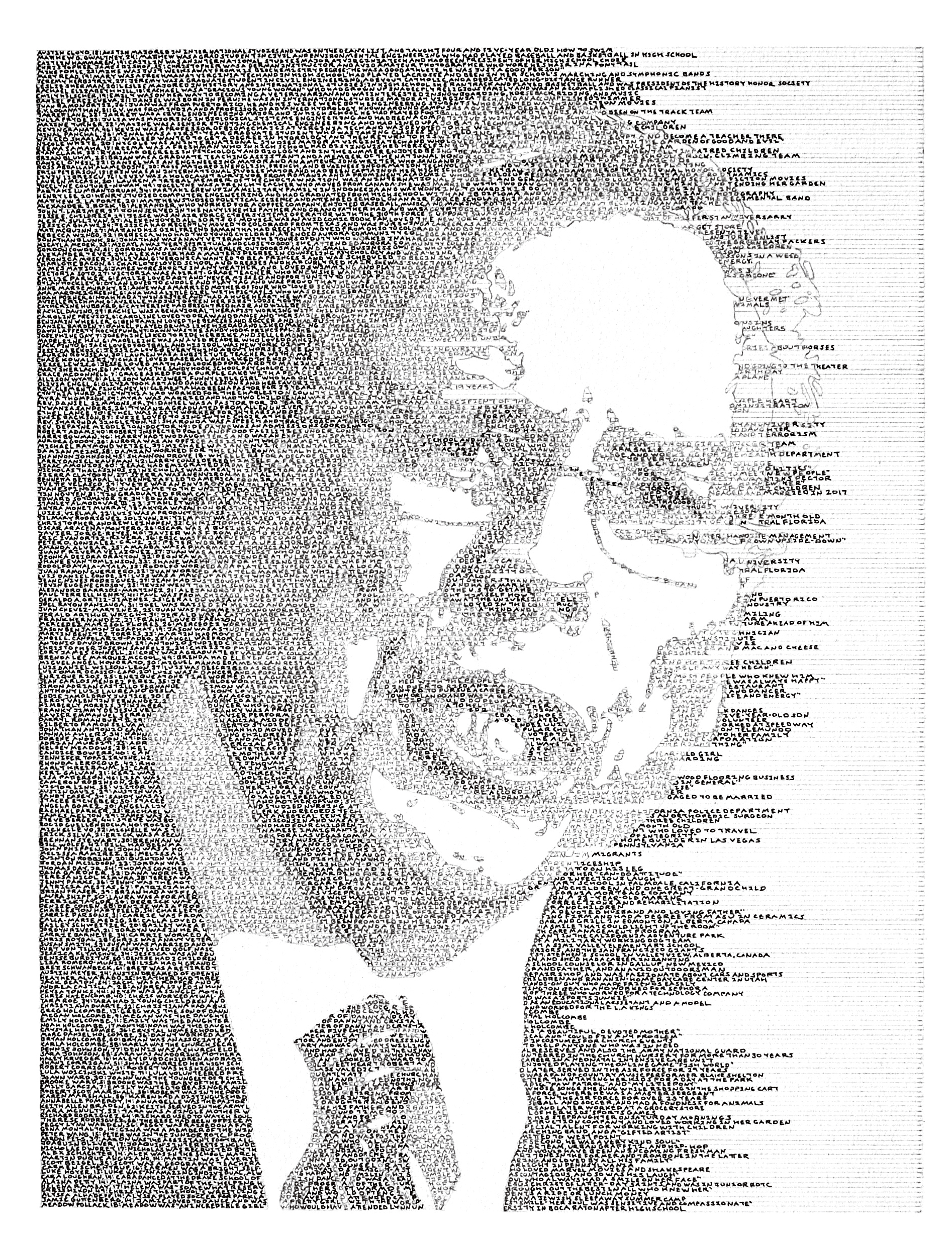

Klauke’s portrait of Malcom X is created from words recalling his account of transcribing the dictionary while in prison.

He does much of his thinking on long walks, followed by two months or so of decision and design — and a cramping right hand.

His portfolio includes Malcolm X, rendered from dictionary entries for every letter from A through X — inspired by Malcolm’s account of transcribing the dictionary in a prison cell. He depicts Barack Obama with words from American writings and speeches, mostly aspirational.

There’s also a scene from West Side Story, using Hamilton lyrics. (Think “immigrants,” if you like. Or think “white people portraying people of color,” and then the reverse. It’s up to you, Klauke says.)

For a recent exhibition at CAM Raleigh, he created a video in which every word in the Book of Revelation flashes by, 20 per second, stark white in a pitch-black room. Again, a bit jarring — an ancient prophecy rendered with the feel of a rushing, technological apocalypse.

Klauke says he selects his subjects “usually for positive reasons.” But there are exceptions.

NRA leader Wayne LaPierre is depicted from information about victims of mass shootings, unfinished like lives cut short.

He rendered NRA leader Wayne LaPierre from the names and brief profiles of victims of mass shootings — the portrait unfinished (as were the victims’ lives) on the right margin.

Klauke also did a pre-inauguration portrait of Donald Trump, called A Man is as Good as His Word, and the words are from demeaning tweets Trump posted. Klauke entered that one in an exhibition at Lake City, S.C. — and braced for the reaction.

“Everybody who saw it was a Trump supporter — and loved it,” he recalls. “They don’t see his words as horrible things. It’s just him fighting back.”

When he’s not creating art, Klauke works amidst it — in the registration department at the N.C. Museum of Art. He grew up in North Palm Beach, Fla., and has lived in Cary since 2005 with his wife, Laura, and son, Jackson.

And he’s finding new ways to play with words. His latest is an experimental epic poem, Achilles Once Again Visits the Republic of Korea, which turns Homer’s Iliad into an absurd tale by running it through iterations of Google Translate.

But Klauke’s favorite work is neither absurd nor contradictory. It’s a portrait of Jackson, at age 9, using text from children’s books and Harry Potter. It captured a special moment, Klauke says, when he was “starting to realize that [Jackson] was growing up.”

He also rendered Jackson as a baby, using a letter he wrote to him about “how his mother and I met.” Klauke says he’ll complete the triptych when Jackson turns 18.

“I tend to be very sentimental,” he says.

— Eric Frederick ’81

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.