Reverse Engineering

Posted on Nov. 16, 2023Force, friction and backlash: This is the story of how Carolina lost its nationally renowned engineering school. Will it come back?

By George Spencer

Call it the last waltz.

In January 1937, The Carolina Inn hosted the Engineers Ball complete with mechanically “revolving prisms, oscillating spectra, mirror reflections, and vari-colored lighting effects,” according to The Daily Tar Heel.

Swing band Freddy Johnson and His Orchestra performed. They might have played Tommy Dorsey’s recent hit “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You.” The melancholy ballad would have been fitting. The ball marked the last time Carolina engineering students — yes, Carolina — would take the dance floor at UNC.

The next year, as a result of a bitterly contested decision by the legislature and the governor and years of public wrangling, any waltzing done by engineering students would happen in Raleigh at the N.C. State College of Agriculture and Engineering, which also had a robust engineering program.

What’s likely known by only a minority of today’s alumni, UNC lost one of the South’s best engineering schools — and almost all of its 268 students, 17 professors and accompanying equipment — giving Carolina the dubious distinction of being one of the few top research universities in the nation without an engineering school.

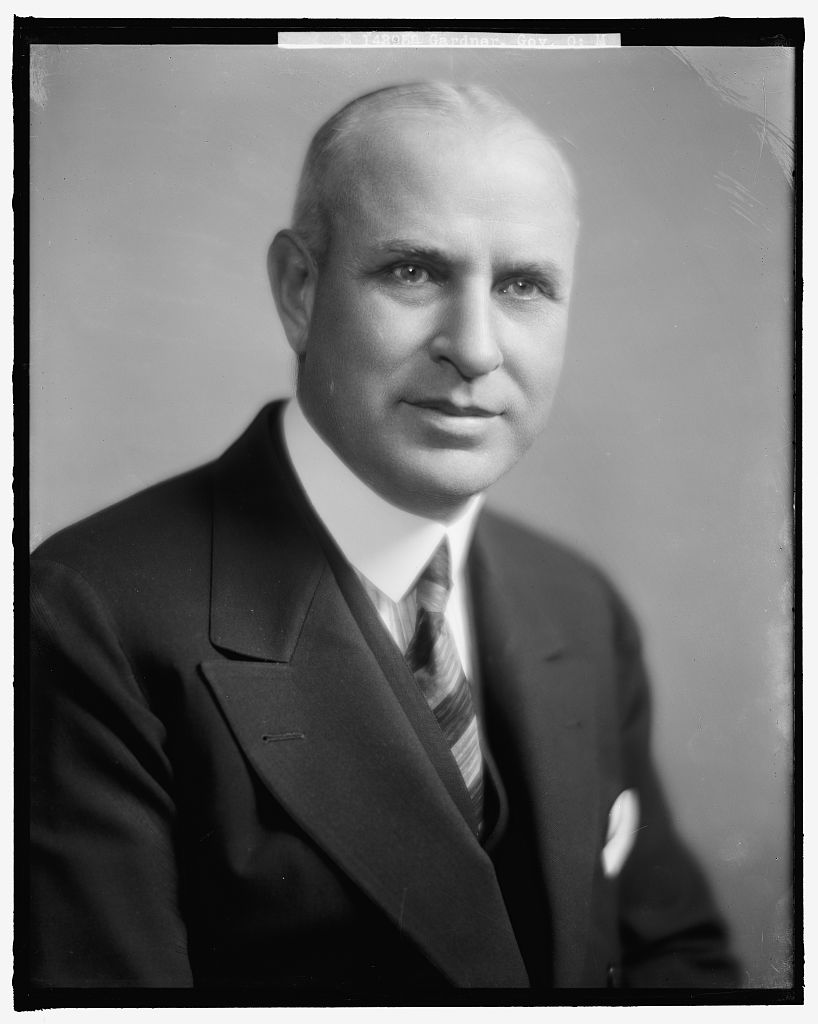

Carolina’s governor, O. Max Gardner (class of 1906) wanted to create a single state-run school of engineering that would be “first rate, like a Southern counterpart of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.” (Photo: Library of Congress)

But the move didn’t happen without a bitter fight. It was the most contentious part of a dramatic higher-education plan by North Carolina’s then governor, O. Max Gardner (class of 1906): the establishment of the North Carolina university system, a change forced by the Great Depression’s brutal financial impact on the three state-funded universities. Costs had to be severely cut. In the end, State College’s business school was also deemed a money-wasting duplication. It would be closed, its faculty and students shipped to Chapel Hill.

A bold goal for engineering stood at the heart of Gardner’s plan. He wanted to create a single state-run school of engineering that would be “first rate, like a Southern counterpart of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,” according to his biographer, Joseph Morrison.

For seven contentious years, from 1930 to 1936, alumni, students and supporters of State College and Carolina would fiercely debate the wisdom of creating a consolidated system, a far-sighted decision whose profound impact on economic development continues to echo nearly a century later. But back then, tempers focused on the fate of both schools’ engineering departments and required the reluctant UNC President Frank Porter Graham (class of 1909) to acquiesce and eventually lead the fledgling system. In the face of the Depression’s misery, neither school wanted to give up its prestigious engineering program, which at the time symbolized the South’s progress.

On what may have been a slow news day — Christmas Eve 1930 — Gardner proposed his vision. At the time no statewide public university system existed. There were three state schools — UNC; N.C. State College of Agriculture and Engineering, which would become N.C. State University; and the N.C. College for Women in Greensboro (now the University of North Carolina at Greensboro). Each was independent and received separate funding.

To make his vision a reality, Gardner, a New Dealer, needed a strong leader who could stand up to and overcome resistance to consolidation from Chapel Hill and Raleigh. His search led him no further than Graham, whom he had championed months earlier to become the new UNC president, now called chancellor. Gardner would later recall that he knew Graham “with his fair sense of justice and fair play would be the ideal man to weld consolidation. … I knew that if we did not have the right man as President [of the UNC System] that consolidation would fail.”

To look at them, the two were an unlikely duo. The governor was broad-shouldered, standing 6 feet 2 inches, and outgoing. He had achieved the unheard-of feat of being captain of the football teams at both UNC and State College, where he earned his undergraduate degree, and foes and friends alike would wonder whether he favored one school more than the other. Graham was 5 feet 6 inches, weighed 125 pounds and had an unassuming manner that belied his shrewd leadership and negotiating skills. He would later be dubbed a communist by his foes for his liberal views and earn the nickname The Fighting Half-Pint of Chapel Hill for overseeing controversies concerning sports, education and politics.

Both Carolina and N.C. State College offered majors in fields such as mechanical, electrical, chemical and civil engineering. Both schools had loyal alumni who were powerful and influential. Both schools wanted to keep their engineering programs.

Unlike Gardner, Graham was a Carolina man through-and-through. He had been senior class president, head cheerleader, editor of The Tar Heel (later renamed The Daily Tar Heel) and, after studying law at UNC, taught history at the University for 15 years.

Gardner got his way. In March 1931, when the consolidation law was enacted, Graham found himself in a most unenviable position. He had been UNC president for less than two years when a new 100-member board of trustees chose him to become the first president of the nascent university system. For the good of the state and the unified system, he faced a wrenching task — shuttering Carolina’s engineering school.

But State College alumni were suspicious of Graham. If he became president of the system, “we shall absolutely be in [his] power, and I see no future for us,” warned Raleigh native David Clark, who was a leader of the state’s powerful textile mill industry and had two engineering degrees from State College.

Both schools offered majors in fields such as mechanical, electrical, chemical and civil engineering. Both schools had loyal alumni who were powerful and influential. Both schools wanted to keep their engineering programs. State had built a national reputation in the 42 years since it held its first classes in 1889. Carolina feared the loss of its engineering program, which traced its origin to 1819, might weaken its science and math departments.

“The perfect storm of things took place in Chapel Hill from 1930 to 1936. Overseeing the consolidation, particularly moving the engineering school, was probably one of Graham’s most difficult policy decisions to bring about,” said William Link, author of Frank Porter Graham: Southern Liberal, Citizen of the World. “Higher education in that period was very politicized.”

A fateful car trip

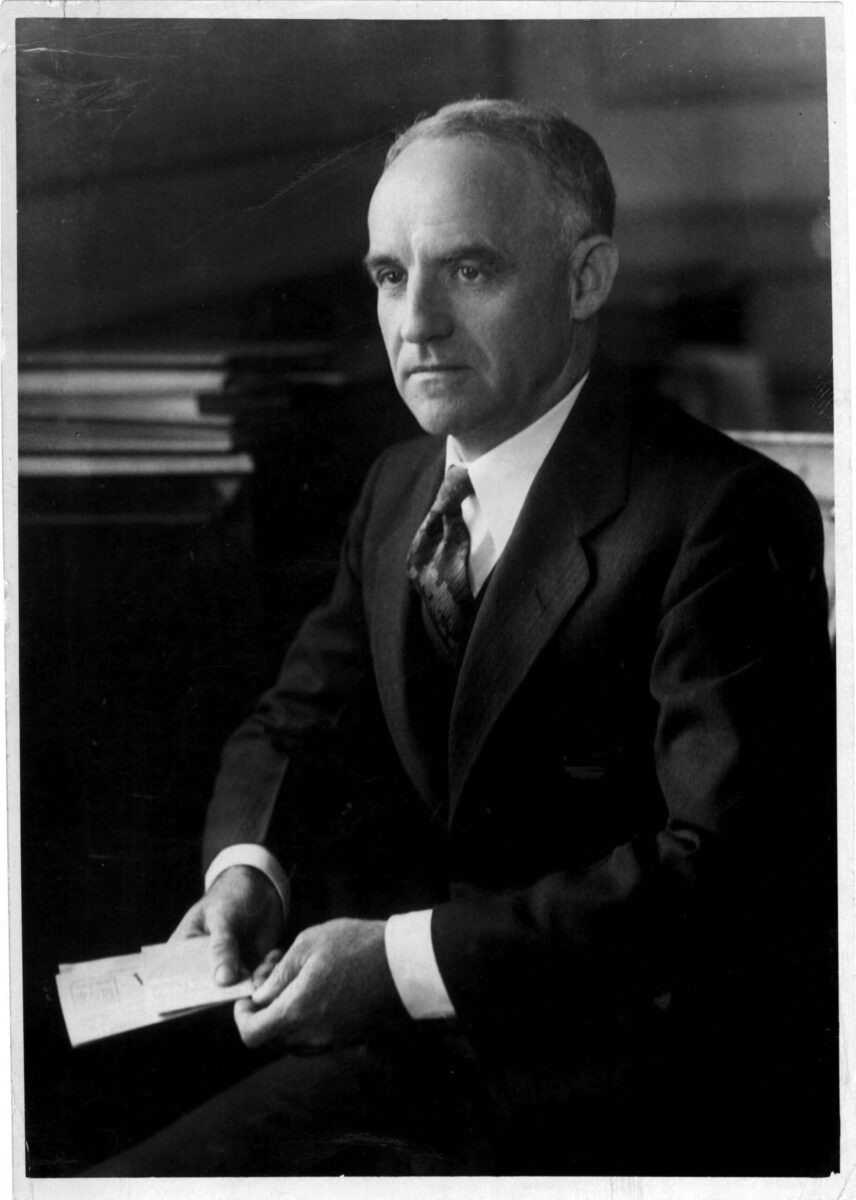

For the good of the state and the newly unified university system, Frank Porter Graham (class of 1909) faced a wrenching task — shuttering Carolina’s engineering school. (Photo: NC Collection, UNC)

In November 1930, just five months after being elected UNC’s president, Graham first heard about Gardner’s plan to ask the legislature to consolidate UNC’s and State College’s engineering schools. Graham’s head must have spun. After all, State College’s tradition and reputation was that of a vocational school. How could it take one of UNC’s crown jewels?

But the Depression was just beginning to ravage North Carolina, and major cuts were needed at the state’s public universities. In the coming year, 1931, more than 50 North Carolina banks would fail. Farm income would collapse. The state’s textile mills and furniture makers would lay off hundreds of workers. State tax revenue would plummet. The legislature had already started to slash State College’s funding, which would ultimately be cut 40 percent between 1929 and 1932. UNC’s appropriations would be gutted 54 percent between 1929 and 1933.

In December 1931, Graham and Gardner took a fateful car trip together after the Duke-Carolina football game. Gardner had counted the votes in the General Assembly. He told Graham the legislature would substantially favor consolidation. UNC would lose its engineering school.

“People talked about trimming fat,” Graham would recall later. “There wasn’t any fat.” Under these financial circumstances, fighting the state on consolidation would have been “suicidal,” Graham said.

But that November, Graham was still unco

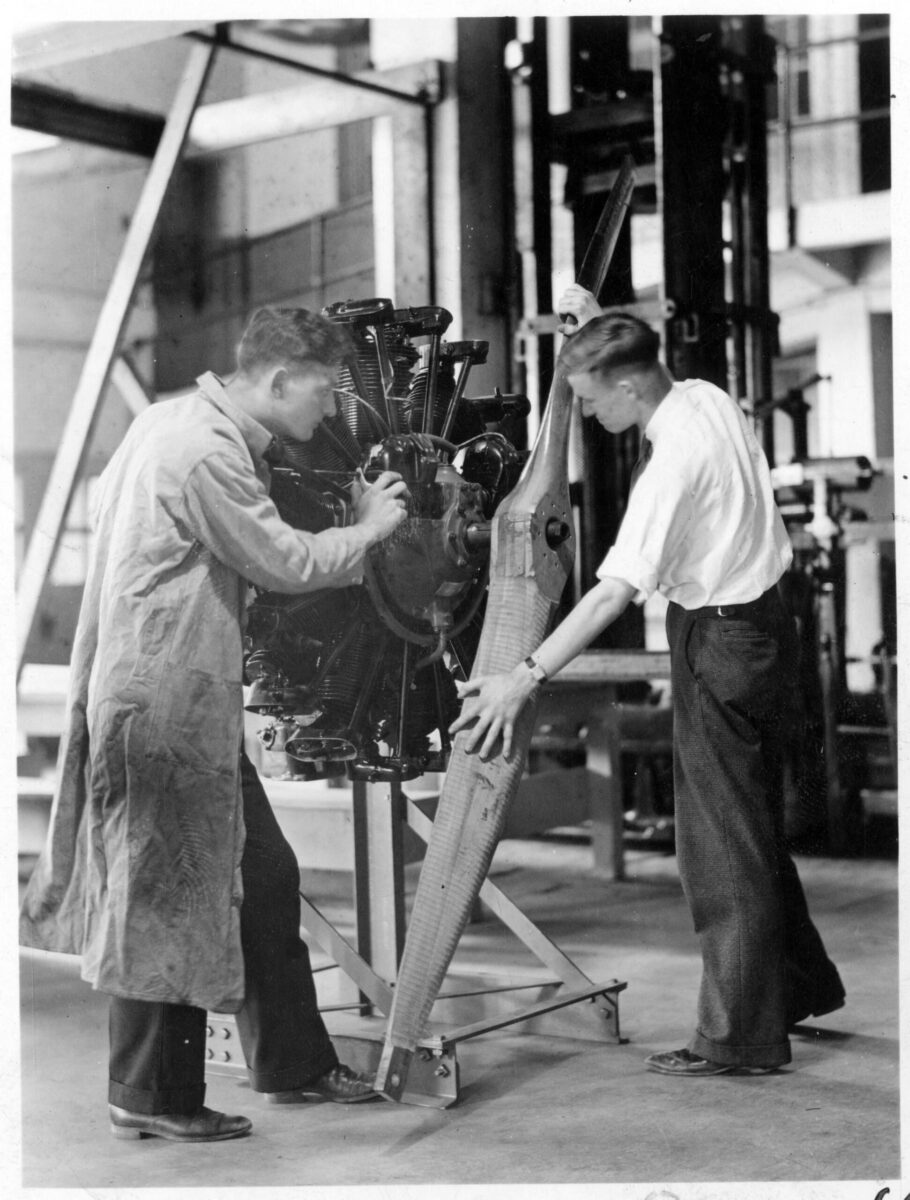

nvinced that UNC had to surrender its engineering program. With 37 staff, professors educated at Harvard University, MIT and Virginia Polytechnic Institute (since renamed Virginia Tech), and 268 graduate and undergraduate students, the school was robust, though smaller than State College’s program, which had about 700 students.

In December, the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C., delivered a report to Gardner, who had asked the research group to find ways to make North Carolina’s government more efficient. The report, the most comprehensive ever made up until that time of state and county governments, called for across-the-board streamlining, notably at the universities. Overlaps in their spending were obvious. Both State College and UNC had business and engineering schools.

That month, Graham and Gardner took a fateful car trip together after the Duke-Carolina football game. Gardner had counted the votes in the General Assembly. He told Graham the legislature would substantially favor consolidation. UNC would lose its engineering school.

Graham shuddered when he heard the news, Gardner recalled. Perhaps with a subtle tone of menace in his voice, he suggested to Graham, “It would be unfortunate if the University was opposed,” according to Graham’s biographer, Warren Ashby, author of Frank Porter Graham: A Southern Liberal.

The ever diplomatic Graham denied he would stand in the way of the legislature. He noncommittally said, “I simply have many questions. One thing I am certain of: If it is not wisely handled, it will split the state wide apart.”

When Gardner asked him how that might be avoided, Graham suggested a commission of higher-education and engineering experts study the matter and that the state merely heed their recommendations. The suggestion became part of the consolidation law the legislature would pass the next year, leaving the implementation of combining the schools up to Graham and the system’s trustees. It might have been that both men knew the report would shield them from criticism of loyal alumni from both schools, who might have claimed the two men had acted rashly or betrayed the interests of their alma maters.

Serving on the panel would require men “with no little vision and who are ‘hard boiled’ enough to ignore howls of and petty politics, even to run rough shod over a few personalities,” Gardner said.

Graham would later reflect he had approached consolidation as having “an open mind with a question mark.”

“Radical and revolutionary”

But the commission didn’t play along. The Survey Committee, appointed by the state’s Commission on Consolidation, released astonishing findings in May 1932. Its education expert, W.E. Wickenden, president of the Case School of Applied Science (now Case Western Reserve University), threw a bomb at the consolidation law. He recommended the engineering school be consolidated in Chapel Hill, ignoring the legislation’s unmistakably clear decree that the combined engineering school would be in Raleigh: “a unit of the University shall be located at Raleigh and shall be known as the North Carolina State College of Agriculture and Engineering of the University of North Carolina.”

The requirement wasn’t good enough for the committee. “In Dr. Wickenden’s judgment the outstanding school of engineering in the South is at Chapel Hill,” George Works, the University of Chicago dean who headed the Survey Committee, wrote in his written report to the trustees. “Wipe out the Chapel Hill school of engineering if you choose, but do not transfer it. The people of the state would hesitate a long time before disposing of the outstanding school of engineering in the South.”

There was another staggering surprise. The Survey Committee also recommended State College and Woman’s College in Greensboro be transferred to Chapel Hill or both be re-created as two-year junior colleges. Neither proposal had even been discussed when the state legislature debated the law in 1931.

Gardner learned about the proposals before they were made public and vaguely informed the press they were “radical and revolutionary.” Unwilling to let the panel derail his plan, Gardner commanded the Survey Committee’s members to say nothing publicly until he met with them. “It was all … Gardner could do to hold [his] tongue,” wrote David Lockmiller ’35 (PhD), a history professor at State College who wrote The Consolidation of the University of North Carolina, published in 1942.

The ever diplomatic Graham denied he would stand in the way of the legislature’s plans to shutter Carolina’s school. He noncommittally said, “I simply have many questions. One thing I am certain of: If it is not wisely handled, it will split the state wide apart.” (Photo: UNC Archives)

Inevitably, the report’s recommendations were leaked. “The report was received in shocked dismay everywhere except in Chapel Hill,” Ashby wrote. After calming outraged State College alumni, Gardner met with the committee in June 1932. The result? Bowing to Gardner’s back-room arm twisting, its report made no mention of the proposals to keep the engineering school in Chapel Hill or transform State College and Woman’s College into two-year schools.

Complicating matters, just a few months later, in November 1932, the UNC System trustees voted to keep the engineering schools at both UNC and State College.

In January 1933, Gov. John C.B. Ehringhaus (class of 1901, 1903 LLB) took office. He assured his friends at State College their school would “not become a red-headed stepchild of consolidation.”

Still, consolidation wasn’t assured. Because Graham, and ultimately the system’s trustees, had the responsibility of combining the schools, Graham’s response was to proceed with caution presumably until the animosity ebbed, and he could meet with trustees, the presidents of the three schools and faculty.

“I am going to go so thoughtfully and carefully and fairly that I know I am going to be disappointing to many people who expect miracles overnight,” he told a friend.

Yet another commission

In 1933, Graham assembled a group of North Carolina engineers and luminaries, including some who were opposed to moving the school to State College, to recommend where the engineering school should be located. He hoped they would reach overwhelming consensus, but they voted 6–5 in September 1934 to move Carolina’s engineering school to Raleigh.

Shaken by the narrow vote, Graham privately sought the advice of the presidents of Harvard, Columbia and Yale universities to gauge whether moving the engineering school to Raleigh was viable. When Graham asked Harvard President Lawrence Lowell if the plan would work, Lawrence replied he doubted it would. “Faculty, alumni and vested interests will attempt to block you at every turn,” Lowell told him.

At long last, in 1935, Graham revealed to newspapers and the trustees his personal decision. He came down wholeheartedly in favor of the merger. “By the logic of consolidation, there should be one engineering school and by the principle of the allocation of functions that one engineering school should be at the college of agriculture and engineering in Raleigh,” he said.

That May, UNC trustees voted 58–11 to accept Graham’s recommendation and rejected by a vote of 50–25 a motion by powerful trustee John Sprunt Hill (class of 1889) to quash the transfer.

The decision unleashed name calling from both sides. A 1935 editorial in The DTH opposed the move saying, “We see it as a dangerous threat by the textilists to wipe this ‘liberal center’ off its feet, because it will weaken us as the decreased appropriations have done.”

The Technician newspaper at State College made its case with numbers. It reported that each engineering grad at Chapel Hill cost taxpayers $1,862 compared with only $891 at State College. What’s more, it observed UNC graduated 20 engineers the year before compared with 112 at State College.

When The DTH dubbed State College “an admittedly second-rate school,” The Technician fired back saying its grads were “professional business men” whose careers would have suffered had they studied in “the admittedly inferior small-town atmosphere of the village of Chapel Hill.”

Harvard’s Lowell was prescient — the uproar continued.

The dean of UNC’s Engineering School, Herman Baity (class of 1917), who earned his PhD at Harvard, continued to advocate for keeping “professional” engineering at UNC and “technical” engineering at State College.

In 1936, trustee Hill led a fire-breathing, last-ditch assault against consolidation. A prominent Durham resident, whom the city’s Herald Sun newspaper called in a 1982 article “a gentle czar,” Hill built The Carolina Inn with his own money, started a bank and a credit union and chaired UNC’s building committee in the 1920s.

In a 24-page pamphlet — titled “A Study of the New Plan of Operation of the Consolidated University of North Carolina” and subtitled “Truth crushed to earth will rise again” — Hill made a case for keeping engineering at UNC. Comparing his “educational politician” opponents to “secret enemies” and “autocrats,” Hill said they “not only counted the chickens before they were hatched but counted the eggs before they were laid.”

Referring to State College’s reputation as a school for technicians, not well-rounded scholars, Hill sniffed, “No matter how high a bird may fly, it must come down to earth to get its living, and the quicker we face about and get our feet at State college on the solid rock of democratic service in the mills and on the farms, the better it will be for us in this rapidly changing world.”

Resentment had grown deep. In 1936, the General Alumni Association reported a survey of its members showed 70 percent opposed the move.

Carolina faculty also opposed the move. In May 1936, after debating for seven hours, they voted 80–19 to request UNC trustees reconsider their decision, the first time professors had rebelled against Graham. “You have offended so many departments,” a faculty member told Graham, “that you couldn’t get elected dog catcher.”

By now, however, the issue was no longer just the location of the engineering school. Graham and Gardner were convinced the entire consolidation effort — uniting the schools, closing State’s business school, moving engineering to Raleigh, establishing a system board of trustees and president — was at risk. “Frank [Graham] never did a braver thing than when he stood up against the strong opposition of his faculty and supported the transfer of engineering,” Gardner recalled. “If we had not won this fight, consolidation would have collapsed in its tracks then and there.”

Hill refused to quit, however. In a stormy 1936 session The News & Observer dubbed “the Battle of Greensboro,” Hill again failed to sway his trustee peers. His motion for reconsideration lost by an embarrassing 50–24 vote.

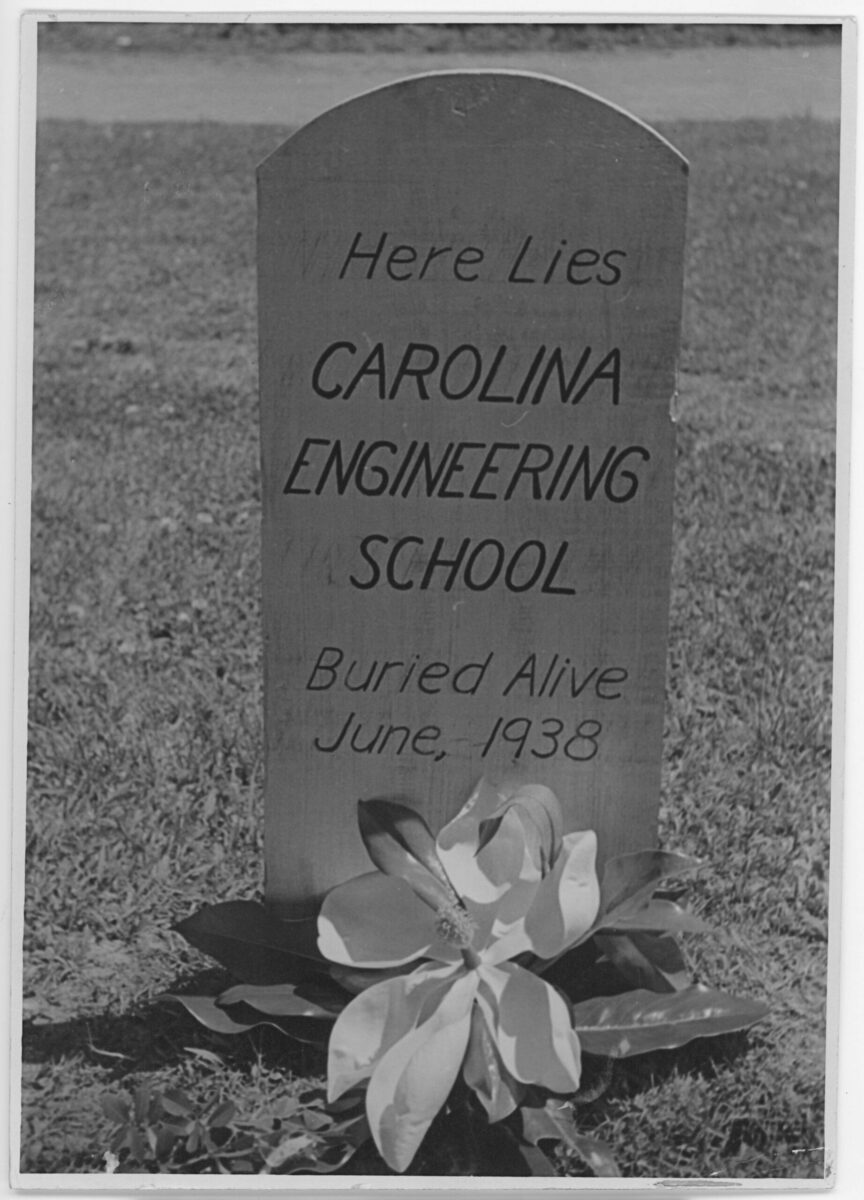

After all classes at Carolina’s engineering school were discontinued, someone erected a mock tombstone in front of Phillips Hall, where the program had been housed. (Photo: “FOLDER 0398: PHILLIPS HALL, 1920–1979: SCAN 8,” UNC COLLECTION P0004, NC COLLECTION ARCHIVES)

Victory belonged to Graham, and Garner’s vision he devised six years prior was vindicated.

Seeking to soothe sore egos, a June 1936 editorial in UNC’s The Alumni Review called on its readers to move on. “Deep understanding and loyalties are much needed,” it pleaded.

As part of the deal and with little fuss, State College closed its business school, and by 1938 almost all of UNC’s engineering professors and students had moved to Raleigh. Former UNC engineering dean Baity stayed and made his own mark in engineering at Carolina. His work in sanitary and municipal engineering was folded into UNC’s School of Public Health, where he led its department of environmental sciences and engineering until 1955.

Nearly 35 years after the engineering school was moved, Baity refused a request by Graham’s biographer Ashby for an interview. He admitted bitterness was the reason.

A badass strategy

Even today, the question remains: Was the decision to move the engineering department to State College the right one?

Graham’s biographer, Link, sees both sides of the issue. “As an educator and person concerned with what a university should be, it should have remained at Chapel Hill,” said Link, who is history professor emeritus at the University of Florida and the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. “But the other hat I wear is that of a political historian, and I think politically it was the smart move to make.”

The consolidation laid the foundation for the expansion of the UNC System decades later to include 16 public universities, Link said, and “was a main driver of modernization in the state.”

Today, engineering remains the most popular major at NCSU. Like Carolina, it is ranked as an R1 top-tier research university by the Carnegie Endowment for the Advancement of Teaching, one of only 146 such schools in the nation. Like UNC, it ranks in the top 1 percent of universities worldwide, according to the Center for World University Rankings. Surveys also routinely place NCSU among the nation’s best engineering schools.

In the end, some engineering survived at UNC, which operates the department of environmental sciences and engineering and, in conjunction with NCSU, the joint biomedical engineering department. Founded 20 years ago, the biomedical school has 50 faculty members and 600 graduate and undergraduate majors. Paul Dayton, chair of the joint biomedical engineering department, declined to be interviewed for this article.

For Joseph DeSimone, the goal now should be all about further cooperation, not bitterness. DeSimone taught chemistry at UNC and chemical engineering at NCSU before joining Stanford University’s chemical engineering department in 2020. And he’s one of only 25 people elected to all three branches of the U.S. National Academies — sciences, medicine and engineering. He believes there’s now enough room and money for both universities to have great engineering schools.

“Strategy is all about being different and compelling,” DeSimone said. “If I were king for a day, I would put a massive engineering building with a red banner on top of it in the center of Carolina’s campus, and I’d put a new cardiac hospital and research arm at N.C. State with a blue banner on top of it. It sounds impossible — that’s what so badass about it.”

A Six-Year Battle to Consolidation

UNC’s loss of its School of Engineering to N.C. State College didn’t happen overnight or without a struggle. Here’s how Carolina’s school was merged with what would eventually become the College of Engineering at N.C. State University.

1930

June 9: UNC Board of Trustees elects history professor Frank Porter Graham (class of 1909) president of the University.

November: Gov. O. Max Gardner (class of 1906) privately tells Graham about his plan to unite the three state-funded universities — Carolina, N.C. State College and the N.C. College for Women in Greensboro — to form the UNC System, which included merging the engineering schools at UNC and State College. December: Gardner publicly announces his plan.

1931

Feb. 13: Gardner’s university consolidation bill is introduced in the N.C. General Assembly. March 27: The N.C. Legislature passes the consolidation law, specifically directing the combined engineering school be located at State College.

1932

May: A committee of outside experts appointed by Gardner to study consolidation recommends keeping engineering in Chapel Hill, shocking and angering State College alumni. June 14: Gardner convinces the committee to relent and support consolidation. November: The newly appointed UNC System trustees vote to support keeping both engineering schools. Nov. 14: Graham is elected president of the new university system.

1933

Early 1933: Recently elected Gov. John Ehringhaus (class of 1901, 1903 LLB) reassures State College alumni the university will be the home of the combined engineering school.

1934

Sept. 4: An 11-member advisory commission of state experts appointed by Graham votes in favor of consolidation 6–5.

1935

Early 1935: Graham seeks advice on how to proceed from the presidents at Columbia, Harvard and Yale, one of whom warns consolidation will not work. May: Graham addresses the impasse publicly and affirms his support for moving Carolina’s engineering school to State College. May 30: The university system trustees vote 58–11 to approve Graham’s recommendation to combine the schools. An opposing minority report by powerful trustee John Sprunt Hill (class of 1889) is rejected 50–25. September: No new engineering students are allowed to register at Carolina.

1936

Feb. 13: General Alumni Association Board of Directors vote to survey Carolina alumni about moving the engineering school; 70 percent say they oppose consolidation. Early 1936: UNC engineering department Dean Herman Baity (class of 1917) and Hill campaign to overturn the trustees’ decision. May 12: In a rebuke to Graham, Carolina faculty vote 80–19 to request the system trustees reconsider consolidation. May 30: System trustees reject a second motion by Hill to keep engineering at Carolina by 50–24.

1937–38

All Carolina engineering courses are discontinued, other than sanitary engineering, which becomes part of UNC’s School of Public Health.

Staff and engineering equipment are transferred to Raleigh.

2023

Sept. 28: N.C. House Speaker Tim Moore ’92 confirms to the N.C. Tribune newsletter he is discussing the possibility of reestablishing an engineering school at UNC.

Classical Mechanics

During the 1800s, “engineering … was not considered a respectable collegiate pursuit,” according to The Making of an Engineer, a history of engineering education in North America. Those overseeing the construction of bridges, railroads and buildings wanted to hire the self-made engineers they had mentored on the job, not bookish types who had pondered classroom theories or studied Latin and literature.By the dawn of the 20th century the nation’s top engineering schools — MIT, West Point — were in the North. Before the Civil War, engineering education had taken root more slowly in the South, and the conflict slowed the region’s progress.

After the war, UNC was swamped with debt, had only a few students and was closed between 1870 and 1875. To finance public land-grant colleges dedicated to agricultural and engineering education, Congress passed the Morrill Act in 1862. But when the law took effect in the 1870s and 1880s, UNC lacked the financial wherewithal to take advantage.

UNC had another problem. “The classical atmosphere at Chapel Hill was perhaps a bit unfriendly to the new democratic ideal of higher education for the masses,” according to David Lockmiller ’35 (PhD), a history professor at State College and author of the 1939 book History of the North Carolina State College. “This attitude, real or imaginary, no doubt convinced many that the true hope for education in agricultural and mechanical arts lay in the establishment of a separate institution.”

In October 1889, the N.C. College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts opened to its first 50 students. (It was renamed in 1917, with the word Engineering replacing Mechanic Arts to better reflect the school’s academic prowess.) Students studied agricultural subjects and mechanical, civil and architectural engineering. They worked in blacksmith, carpenter and machine shops, and ran the school’s electric plant.

The Morrill Act required State College to deliver “classic studies,” but not until 1906 did the school offer modern language courses. Detractors at UNC regarded such inattention to the liberal arts as evidence of State College’s inability to offer engineers a well-rounded education. In 1935, arts and sciences courses made up 45 percent of the classes required for a UNC engineering degree.

“Engineering is becoming more intimately connected with law, economics, and psychology, which are better centered in a university than in a distinctly technical school,” the student editors of The Carolina Engineer magazine wrote in 1934.

UNC’s program had a better national reputation, but State College was a scrappy underdog. The school built a strong athletic tradition, with teams often called the “Red Terrors,” their spirit reflected by their fight song: “Scrap ’em, men, hold ’em fast/You’ll reach victory at last.”

The loss of Carolina’s engineering program was a bruising blow. But consolidation of the universities into a statewide system proved in the long run, most believe, to have been a smart move that helped make the state an economic powerhouse.

— George Spencer

Will UNC Engineering Rise Again?

The hurt feelings of the 1930s over consolidating the engineering schools at UNC and N.C. State College may have been buried long ago, but could the same animosity return in the coming years?

Maybe, if N.C. House Speaker Tim Moore ’92 can convince enough of his fellow lawmakers that reestablishing an engineering school at UNC is a good idea. In September, he told the North Carolina Tribune, a business publication launched last year to cover state government, that he has been talking to other state legislators about bringing back engineering to Carolina.

Moore believes North Carolina needs another engineering school to position itself to meet what is expected to be a growing demand for their skills, and Carolina is the proper place to house another institution. He has contacted members of the UNC System Board of Governors to gauge whether there is any interest in bringing engineering back to UNC, the Tribune reported. But there’s no word on whether anyone thinks so. The 2023–25 state budget did not include funding for a UNC engineering school, and Moore believes it will be some time before a school comes to fruition, if it ever does.

“It’s something I’m interested in,” Moore told the Tribune. “But I think it’s an idea that’s going to need to work its way through the process.”

Moore did not return calls for comment.

Speaking at the Oct. 6 meeting of the UNC Faculty Council, Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz acknowledged there has been discussion in the state Legislature about bringing engineering back to UNC. “There’s been talk of, ‘Why doesn’t Carolina have an engineering school?’ especially when we have a department of applied physical sciences,” he said. “I don’t expect that [engineering school] to come anytime soon.”

North Carolina has engineering schools at NCSU, the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, N.C. A&T State University, and Duke University.

Whether UNC regains its engineering school or not, if the past is any indication, one thing is certain: Expect a similar feud to erupt if Moore’s plan gains traction.

— Cameron Hayes Fardy ’23

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.