Room for Rant

Lewis Black ’70 thought writing plays was his future, until he realized it wasn’t.

by Claire Cusick ’21 (MA)

On a Friday evening in November, Lewis Black ’70 sat inside his tour bus parked on South Mangum Street next to the Durham Performing Arts Center. It was about an hour before he was due onstage for the Nov. 12 stop on his 2022 tour, which had begun in January in Denver, then hopscotched across the country to 60 stops from Maine to Michigan to New Mexico. He and his four-man support crew had driven from Marietta, Ohio, after the previous night’s show. Opening act Jeff Stilson hopped off the bus to head inside the theater. Black and his staff welcomed two visitors onboard.

Black, already dressed in a suit, sat at a small table scrolling through an iPad, reviewing complaints about everyday irritations that fans had submitted to him online, looking for ones to include in that evening’s show-after-the-show, which also would serve as a taping of his podcast, Lewis Black’s Rantcast. It’s a bonus performance for those in the audience. After he finishes an hour of his own material, he returns to the stage with the iPad, editing on the spot what he believes to be the funniest submissions and reading them with his signature indignation.

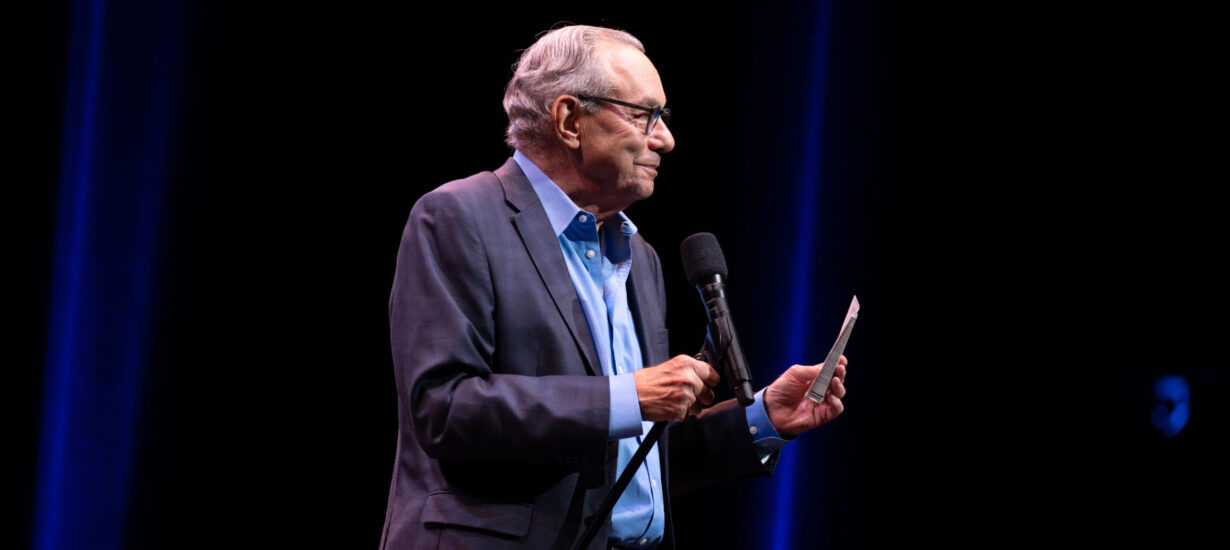

Lewis Black performs at the Durham Performing Arts Center, the closest stop to the UNC campus along his current tour, on Friday, Nov. 11, 2022.

At 7:45 p.m., the group left the bus, entered DPAC’s quiet backstage halls, its walls signed by previous performers, and wound around to a small dressing room. There, officials from Carolina Performing Arts waited to greet Black, offering him a bag of Carolina swag. In person, Black is polite and warm, still curmudgeonly, but not his unhinged stage persona.

Black’s longtime friend and fellow comedian Kathleen Madigan said he is not irate all the time. Just sometimes. “He’s probably nicer than me offstage,” Madigan said in an interview. “People don’t expect that out of him. He’s actually kind of the flip side of what he is on stage. But that is part of him, so it’s not like it’s made up just for stage. It just doesn’t come out 24-7.”

After Stilson finished his set and the intermission concluded, Black walked onstage to screeching death-metal music, which he allowed may have been a bit much to herald the arrival of “one aging Jew.” It was his first laugh of the night.

Catharsis

In Durham, and Austin where he had appeared 10 days earlier, Black began by explaining a nuance of comedy, a lesson he apparently believes is necessary in the current culture. If you are offended by a joke, he said, don’t laugh. It’s that simple. The comedian onstage is not attacking you, he explained. And if you think you’re being attacked, that is on you.

Black gave detailed instructions on how to handle such a situation, in case it happened that night. “In your head, say bye-bye,” he said. Then the joke will be gone. Jokes are contextual and ephemeral. Don’t worry about it, he said. The most effective way to let a comedian know you didn’t like their joke is to simply not laugh. “If it’s not funny, don’t laugh,” he said. “That’s your power.”

And don’t get riled thinking that comedians have any real influence, Black said. He has been railing against war, politicians, government and just about everything else for decades. “Since I’ve been doing comedy, [expletive has] just gotten worse,” he said. Let’s have a good time, he tells the audience.

He then dove into his bread-and-butter material. He took jabs at himself, and even his mother, who had died recently at the age of 104. She lived so long that the details of her funeral arrangements had become outdated, Black said. Someone had called to tell him the urn she had requested for her ashes was no longer manufactured. “She outlived! THE! URN!” Black yelled. The audience laughed.

Black is good at ranting. His talent is to say what many in the audience think privately. He expresses it better than they could have. His voice growls, his face grimaces, his fingers point. It’s as if the common-sense response to everything that’s stupid and unfair found its perfect grouchy oracle.

Jerry Seinfeld once told Black that Black’s fingers were the key to his whole career. “When your fingers get going, and they start working, they’re like little sparks of lightning,” Seinfeld said. “And it’s funny.”

Watching Black perform makes you laugh in relief at your complaints about common annoyances. Finally! Someone gets how trapped you feel stuck in traffic, how despairing you feel trying to decide whom to vote for, at the latest idiocy or injustice across your news feed. You feel heard. You laugh. It’s cathartic.

Black isn’t afraid to take on subjects that many comedians avoid, especially jokes that may invite hecklers and can provoke people — whose social guardrails may been removed by alcohol — into arguments. “Clubs are bars. It’s not a theater, where people are just gonna be polite,” Madigan said. “People are gonna heckle. People are gonna get thrown out. People are drunk.”

But Madigan has watched Black, whom she met at Catch A Rising Star in Chicago more than 25 years ago when she was the opening act and he was the headliner, do it well. “To try to bring what I would call harder topics into that is gutsy,” she said. “I always would just sit in the back of the room and watch and go, ‘I would never do any of that.’ I admire that he does. But I don’t have it. … I don’t want to fight with people.”

Black has performed intolerable irritation on Broadway and USO tours. He has won multiple Grammy Awards for comedy albums. He is so closely linked to his angry persona that when the creators at Pixar movie studios were pitching Inside Out, a 2015 Oscar-winning film about a child dealing with conflicting emotions, they first thought of anger — and pictured Black.

“We used Lewis Black as an example of casting when we were pitching,” director Pete Docter said in an interview promoting the movie. “But everybody else, we designed the characters without having particular actors in mind, and then only later we would listen to a list of people.” Black is set to reprise his anger role in Inside Out 2, scheduled for release next year.

Love at first sight

How a man from the Washington, D.C., suburbs became synonymous with one emotion was a circuitous one. Black visited Carolina sometime in the mid-1960s, when the Vietnam War and civil rights protests were raging and youth were questioning traditional gender roles and experimenting with drugs. He had spent his first year in college at the University of Maryland, living at home with his parents in Silver Spring, Maryland. But he wanted to transfer to another university to live the life he imagined that college students lived, he wrote in his 2005 memoir, Nothing’s Sacred. His visit to Chapel Hill was a side trip; Black was on his way to Durham, where he planned to apply to Duke University.

But standing on Franklin Street and gazing at Polk Place changed the plan. “I walked onto the campus of UNC, however, and that was all it took. It is as close as I had ever been to being in love at first sight,” he wrote in his memoir. “I had found the ideal campus for me. I decided at that moment that this was where I wanted to go to school. I felt like I was home — a wonderful home where my parents didn’t live, a home where there was adventure and drugs and sex.”

If his memories of Jubilee — the infamous campus music festival that peaked during his undergraduate years — are any indication, he checked off at least two of those three goals, as he told the Carolina Alumni Review in 2021. He still remembers the incredible music in 1970, such as B.B. King, Joe Cocker, Rita Coolidge, Chuck Berry and James Taylor. And in 1971, when Black was working on a postgraduate fellowship, Jubilee featured the Allman Brothers. “Get here,” he remembers telling friends at other colleges. “You’re not going to believe what’s going on here.”

Black returned to campus last spring to visit with students and share lessons from a career spent writing and performing. He also donated his papers and memorabilia to the Southern Historical Collection at the Louis Round Wilson Library Special Collections. It wasn’t his first time back; he kept an apartment on Franklin Street for years. Nor was it his first time interacting with students; pre-pandemic, he would come to the University to help students produce the Carolina Comedy Festival and perform as its headliner for more than 10 years in the early 2000s. In 2022, he told students in Professor Michelle Robinson’s American Studies class on comedy and ethics that having the library ask for his papers meant more to him than a Grammy. “Much more,” he said.

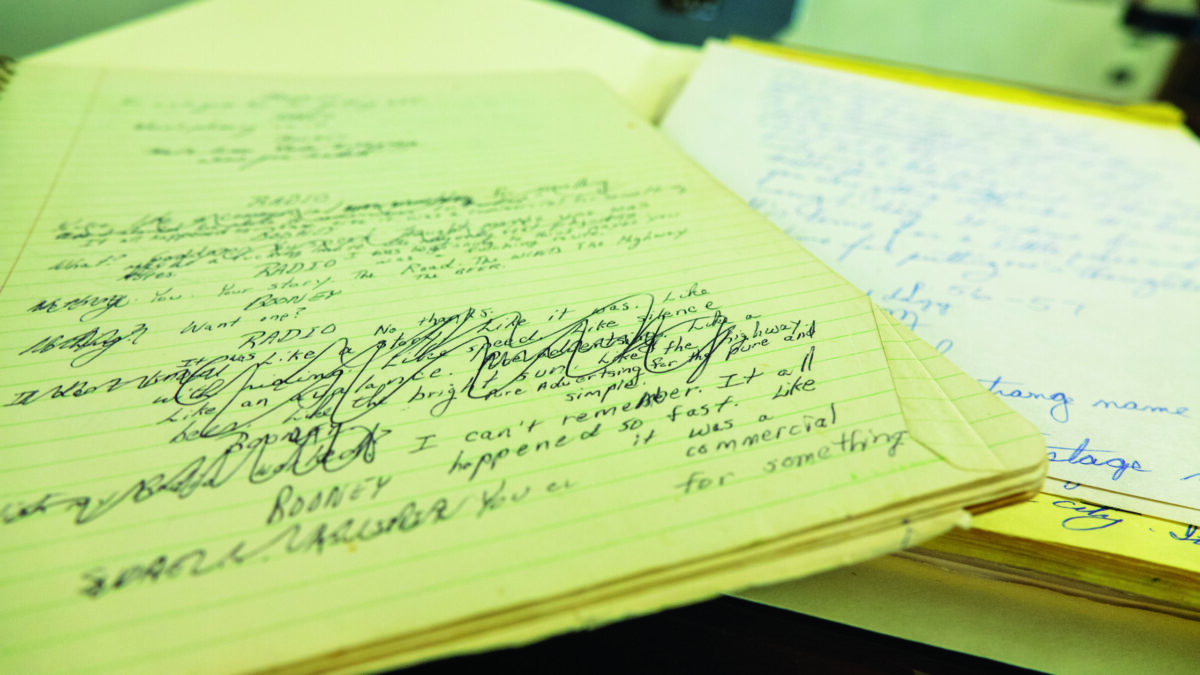

The Lewis Black collection contains more than 6,000 items, including scripts for television pilots and ephemera from his acting career. But the core of it is more than 40 plays, rough drafts and workshopped versions for each, from the decades Black spent pursuing a career as a playwright. Feast, a coming-of-age play that Black wrote while he was a Carolina student, sold out its run at the Great Hall at the Carolina Union and toured other colleges in North Carolina with help from a grant from the N.C. Arts Council.

Black still remembers the thrill he got when Feast received a standing ovation in Greensboro. “I turned to this friend of mine and said, it’s never gonna get any better than this,” he recalled. “I should have walked away at that point, but it was so much reinforcement that it was like oh, like wow, yeah, I can do this again.”

After he graduated from Carolina, Black was awarded a Shubert Fellowship for playwriting, and he stayed in Chapel Hill for a year. He graduated from Yale School of Drama and enjoyed some success as a playwright. The Deal, a dark comedy about business, was made into a short film in 1998. In 2011, his play One Slight Hitch was produced at the Williamstown Theatre Festival and then again in 2012 at both the ACT theater in Seattle and the George Street Playhouse in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

But by then, he had become more successful as a comic. His first attempts at stand-up were at Cat’s Cradle during his fellowship year in 1971. But Black said he was awful. He continued pursuing his career in theater and sometimes did stand-up comedy on the side for fun.

Convincing theater owners to read a play was akin to sending a message in a bottle, he said in an interview. But during a stand-up routine, the feedback is immediate. Back to that fundamental lesson of comedy: The audience either laughs or it doesn’t. “I really was doing it as a way to kind of get my writing out there,” Black said in an interview. “It had nothing to do with the fact that I believed that I would become a stand-up. I really wanted to be in theater. I wanted to be a playwright.”

An experience in Houston in the early 1990s finally broke him of that dream. The Alley Theater had told him they wanted to produce his musical, The Czar of Rock and Roll. He was asked to expand the one-act play to two acts. He also was asked to update the time references, because the play was about the Soviet Union, which had recently collapsed. There were more requests and more hassles. Black was asked to stay in Houston to work on them, but he didn’t have money to pay for a place to stay. He went to a local comedy club, Spellbinder’s, and auditioned with a 15-minute routine. The club hired him, and when its headliner dropped out, it hired him for the entire week.

“They’d only seen 15 minutes of work and did that,” he recalled. “And I went, what’s wrong with this picture?” He had busted his hump trying to make it in theater. “And now I walk into a bar filled with drunks … and they’re going to pay me the same amount as I was getting for my play, for one week.” They gave him a better place to stay and provided him with a car.

“And I went, that’s that. I can’t do this anymore,” Black said. “I can’t fight this. My joke has always been, working in the theater … for me, was a lot like working in an abusive orphanage.”

Lewis Black backstage in his dressing room before his performance at the Durham Performing Arts Center, the closest stop to the UNC campus along his current tour, on Friday, Nov. 11, 2022.

“I need you”

Reading other people’s rants is Black’s latest project. He’s the longest-running contributor to The Daily Show, outlasting its three hosts. His final Back in Black segment for the show during its Trevor Noah era took on young people who were signing up for retirement-club discounts (to save money) and taking advantage of early-bird dining (to save money) — seven minutes of jokes about the young and old and the ways the world has turned upside down.

“Are you [expletive] me?” he yelled. “Old people eating early is part of the social contract! Old people get to eat early, and in exchange, young people get to not watch old people eat.”

He enjoys reading other people’s rants. During the pandemic, when he was stuck at home, producing the Rantcast allowed him to stay in touch with his audience. “With my own comedy, I need an audience,” he said. “If you give me a rant, I don’t need an audience, I know exactly how to get the laughs on it.”

The rants from Durham ended up as part of episode 106 of the Rantcast. All were funny thanks to Black’s delivery. Submissions ranged from gripes about daylight saving time, to DPAC not serving mustard, to former N.C. Labor Commissioner Cherie Berry, to a diatribe anticipating family visits during the upcoming holidays. “Why do we do this?” Black read. “For once, can we just start the Thanksgiving season by saying … ‘I’m not coming, because you’re an idiot, and your pumpkin pie tastes like regret.’ ” That one got a big laugh from the DPAC audience and an appearance on Black’s Instagram feed.

When he was through, Black emoted a bit of vulnerability and kindness. Before leaving the stage, he thanked the audience several times. “You’re the primary relationship in my life,” he said. “I need you.”

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.