The History Superstore

Nick Mueller came to Carolina to finish preparing to teach history.

Soon afterward came a monumental distraction.

by David E. Brown ’75

Just inside the entrance, you are greeted by a man past 90 years old who endured that winter in the Ardennes Forest. The next day, a different man, a medic who earned two Bronze Stars in Italy. Their backdrop, hanging from the ceiling, is a C-47, the plane that dropped paratroopers behind the lines at Normandy. On the floor is a Higgins boat that dropped the infantry in the surf.

This is the warmup to a fascinating, often agonizing tour of the time and the places where the American experiment in democracy was threatened like never before or since.

You step off the platform onto a Pullman car, in the footsteps of a boy who might have been leaving home for the first time, riding off into the unknown to confront the unimaginable.

Down in the warehouse district of New Orleans, where a modest idea hatched over drinks in a backyard gazebo grew into the dominant feature of this part of town, and grows yet, artillery thunders, sirens wail, smoke billows, the floor shakes. A Sherman tank that was right here yesterday has been driven elsewhere today.

PT-305, which looked like this during the war, soon will ply Lake Pontchartrain near the museum. See video and a graphic of PT-305 restoration and video of “Aircraft Return to Flight” at alumni.unc.edu/WWII-museum. (Photo courtesy of National World War II Museum)

Veterans walk the hallways, not so much to be thanked for their service as to share it. By next year, it’s expected, the last operational PT boat will roar across Lake Pontchartrain with museum visitors on deck.

There is an old joke: What do you do with a history degree — open a history shop? In Nick Mueller’s case, a superstore.

The teaching career he planned when he left Chapel Hill with two advanced history degrees, a master’s in 1964 and a doctorate in ’70, was all blown up over the next 20 years in the course of an ambitious academic foray into the Europe he’d seen as a child and an improbable dream nurtured with a colleague and neighbor, the author Stephen Ambrose.

As the vets of World War II depart — the last will be gone in about 20 years — the National World War II Museum rises in the city where Mueller and Ambrose taught and, more poignantly, where Andrew Jackson Higgins developed and tested the beach landing boats used at Normandy and in North Africa, Italy and all the Pacific landings. In 1964, Dwight Eisenhower called Higgins “the man who won the war for us.”

Ambrose endowed the museum with thousands of artifacts that veterans had given to him over the years and thousands more oral histories he’d collected from them. Then he barely got to see it off the ground before he died in 2002. Mueller has shepherded it since it opened in 2000 with 265,000 square feet over six acres — headed now toward 330,000. They courted Ted Stevens and Daniel Inouye, war veterans who led U.S. Senate appropriations for many years from opposite sides of the aisle. The professors drew in two others with passions for the war efforts: Tom Hanks, who supplied Hollywood production values; and “greatest generation” champion Tom Brokaw.

Plagued with funding problems, the museum had missed opening deadlines three times. A 23-member board dwindled to eight or nine as people gave up. Mueller did not. Nor did he when Hurricane Katrina laid waste to the city. Now, a modest walk but a world away from the famed French Quarter, the museum has been rated for three years by TripAdvisor as New Orleans’ No. 1 attraction.

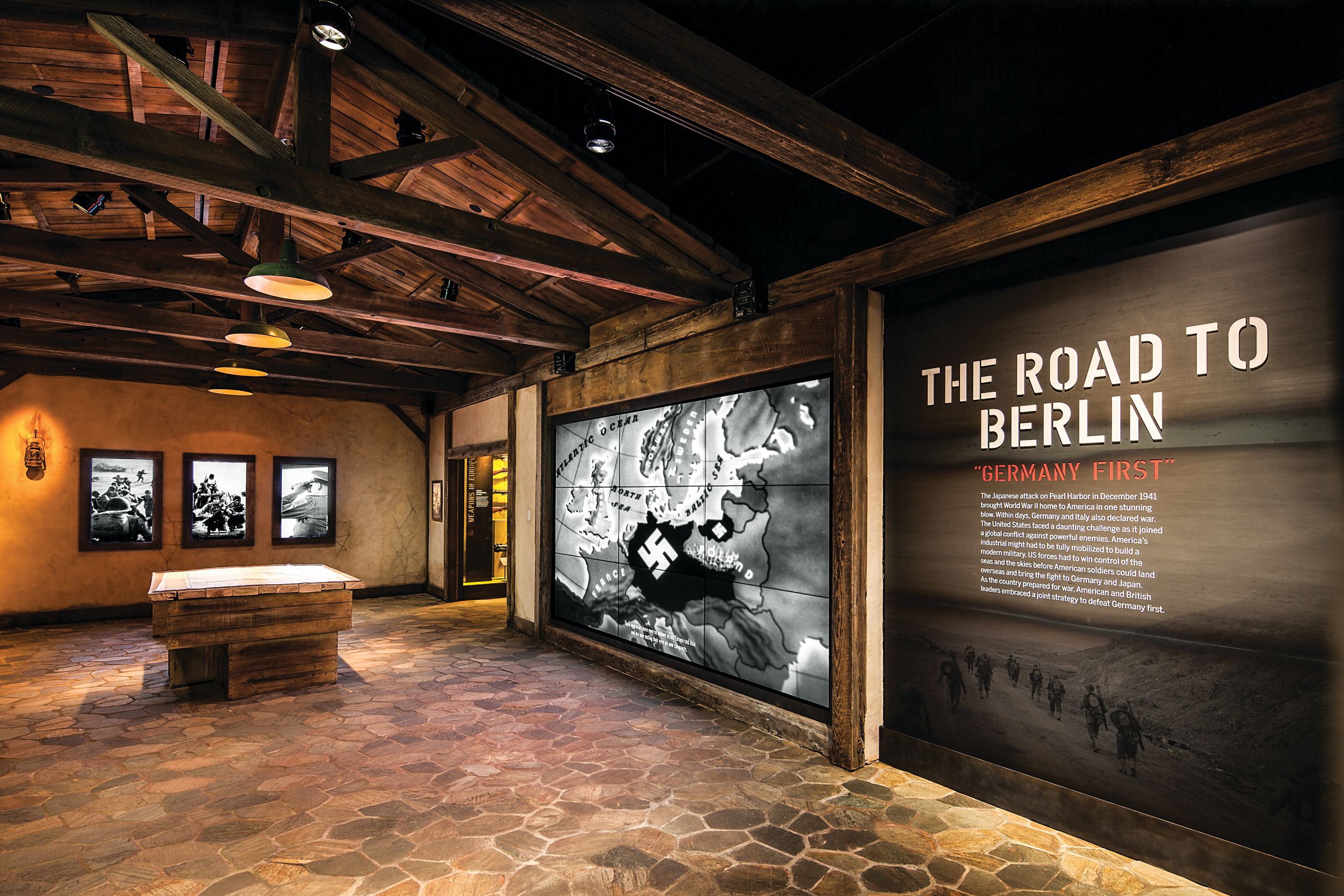

The museum visitor’s journey starts on a rail car in which the windows are video screens that portray leaving home for war. It continues, below, on a long, winding walk through the European campaign; more recently, a similarly structured Pacific campaign gallery has opened. (Photo by Jonathan Bachman/AP Images for the Review)

An epic moment

Every war since has brought cries of “why?” World War II’s question was simply “how?”

Someone in administration at Carolina once commented about the student body in the early 1940s, as neutrality began to wither away: “The number of deferments asked is none.” There was resistance, to be sure. Pearl Harbor took care of much of that. Before long, the University was researching malaria, developing war materiel manufacturing processes, testing gas masks. Students and faculty left to join the sacrifice; a Navy training program turned Chapel Hill into a war town.

The visitor’s journey continues on a long, winding walk through the European campaign; more recently, a similarly structured Pacific campaign gallery has opened. (Photo by Jonathan Bachman/AP Images for the Review)

That tells you something. The wisdom of Vietnam and the Middle East conflicts will be debated forever. WWII was all-in.

It was Ambrose’s idea to start a museum focused just on the Allied landings in Normandy in June 1944. It was Mueller, a specialist in European diplomatic and intellectual history, who helped Ambrose broaden his scope.

“It’s not just an amphibious assault,” Mueller said. “I said, ‘Steve, you can’t talk about the landings just as invasions.’ This is an epic moment. This is really what I wanted visitors to understand about this.”

A study of the Holocaust Museum in Washington helped Mueller focus not on things but on narrative. “How do you do a history museum without any artifacts? They had a compelling way to tell the story, [and] they were doing it with images around the principle of less-is-more. Military museums up to that point, the artifact was king. So what the Holocaust Museum showed us all was that the story is everything.”

Mueller, who as founder and then CEO has had his hands in the details, says he feels a “tremendous responsibility to tell it right.”

“It’s a time when everything was at stake for the preservation of the country that we still have as a result of the Allied victory in World War II. My feeling is, both from training and conviction, that this will be one of the biggest events in the world forever. People have high expectations as to how you tell that story.”

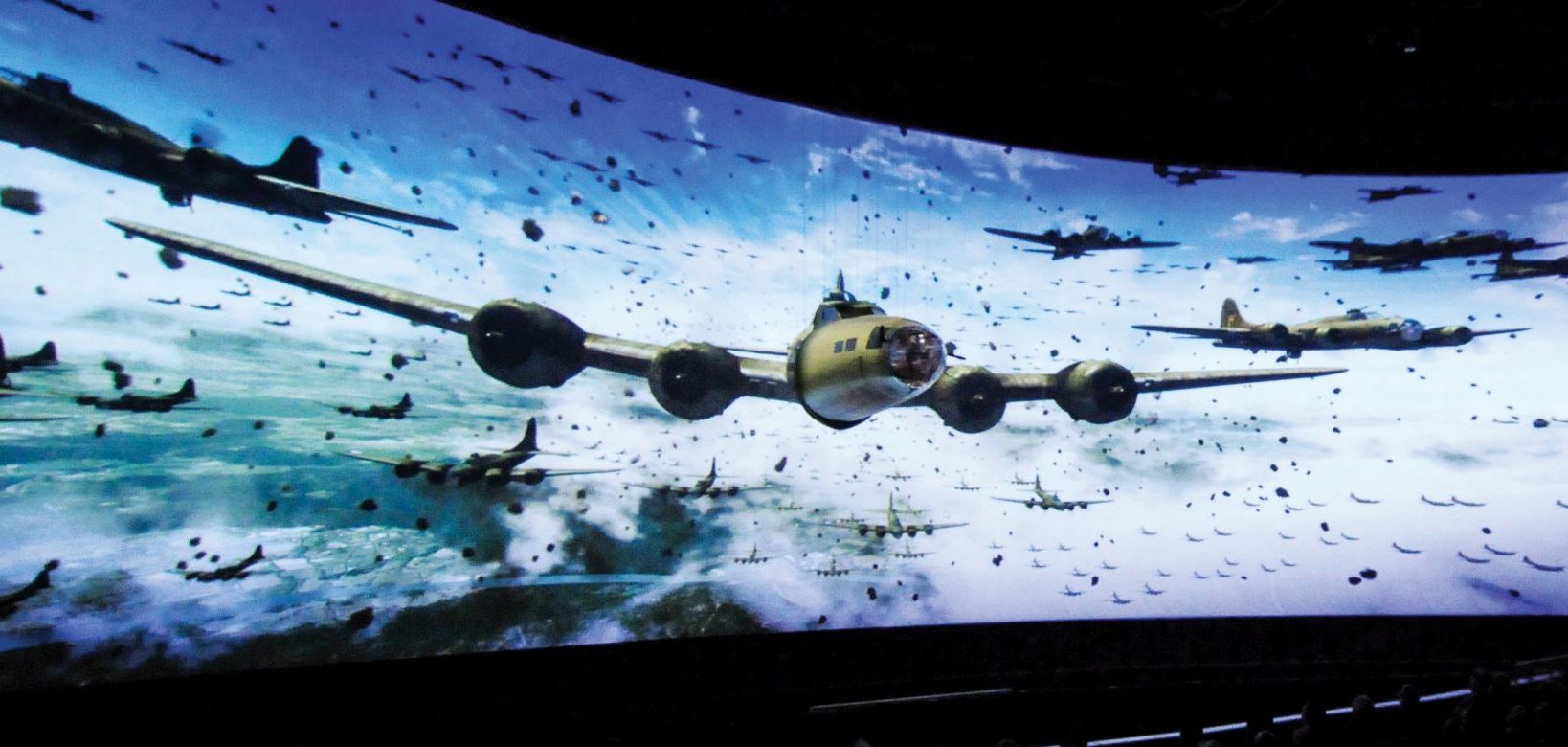

A $5 upcharge gets the visitor into “Beyond All Boundaries,” a 40-minute extravaganza produced by Tom Hanks and his friends at Universal Studios that attempts to capsulize the war through film and special effects. The extra is well spent, and the notice that it may be too intense for young viewers is no joke. See a video for “Beyond All Boundaries” at alumni.unc.edu/WWII-museum. (Photo courtesy of National World War II Museum)

European summers

Mueller’s father immigrated from Germany to Brooklyn, N.Y., in 1923. He was a professor of church history.

“He was crazy about America through his father and grandfather before World War I,” Mueller said. “Our house was filled with scholars and historians — pretty famous, because he was.” His father came of age between the wars; he wrote a manuscript that was confiscated by the Nazis in 1936.

His father took him to Germany, Austria and Switzerland at 14, a trip that would inspire important developments for both the University of Innsbruck and the then-nonexistent University of New Orleans.

“My dad would drag me off to every monastery and library because that’s where he wanted to go. He created in me a love of history and just a general intellectual curiosity. He just had an amazing sense of curiosity and wonder about the world. So I just grew up surrounded by that.”

Mueller started at Stetson University in Florida as an English major, but Europe was pulling on his coat. Without the money for a whole year, he made it to Vienna for a summer.

“To study art history and philosophy and history in the heart of central Europe with field trips to some of the best professors in Europe, it just blew my mind. I said, ‘Well, my dad wasn’t so dumb picking an academic career.’ ” That’s when Mueller decided on graduate school, and Carolina was at the top of his list. He got a couple more years in Europe between his graduate degrees.

He started teaching at what then was Louisiana State University at New Orleans, an ambitious commuter school.

Unless you’re fascinated by humidity, you do not want to be in New Orleans in the summer. “The chancellor was ready for anybody to try anything that would provide more opportunities for our students,” Mueller said. “I said, ‘I’m gonna take 200 students to Europe if you’ll give me the green light and about 25 faculty and offer 50 courses in a six-week summer school.’ And everybody thought I was crazy.”

He started in Munich in 1973, then moved the program to Innsbruck.

“When you combine intense academic instruction that doesn’t always sit in the classroom but is walking in the streets and in the museums and the art museums and the monuments and the battle sites, history comes to life in a way that it’s almost impossible to replicate. It becomes life-changing for people, I think, both intellectually and maturity-wise, and you also become very aware of the many different cultures that are compressed around you.

“We told professors, ‘You can’t just teach your regular course. You’ve got to be out in those cities.’ We kept classes small so professors could travel with their students.” He expanded the program from history to studies in business, art, music and science. By the early 1980s, it became an exchange — Innsbruck students were studying America in New Orleans in the winter. Mueller, who had moved into administration after teaching for 11 years, managed both sides.

“It was Nick’s engaged personality and efficiency that had such an impact on the partnership,” wrote Anton Pelinka, the first Innsbruck professor to teach at New Orleans, in an essay about Mueller’s career. “World politicians have visited Innsbruck, thanks to Nick Mueller and the trans-Atlantic cooperation he initiated between the two universities. He helped immunize this friendly university and city partnership from the political ups and downs.”

Now in its 42nd year, the Innsbruck program has hosted more than 10,000 students.

“I was chasing my own passion, my own dream,” Mueller said, “to give people the same kind of experience I had.”

Mueller was in the habit of stopping by Ambrose’s house on the way home from work. In about 1990, UNO asked Mueller to lead development of a research park on Lake Pontchartrain. That’s about the spot, Ambrose told him one day in his gazebo, where he wanted to start a D-Day museum. (Photo courtesy of National World War II Museum)

A big idea starts small

Mueller and Stephen Ambrose first bumped into each other in 1971, when Mueller was on the recruiting team to bring Ambrose back to UNO after some academic wanderings.

He “was my best friend of 30 years,” Mueller said. Ambrose included a chapter about Mueller, titled “Dearest Friend,” in a short book he wrote about friendships, in which he acknowledged that he’d taken Mueller’s direction on his D-Day, Band of Brothers and biographies of Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, and Lewis and Clark.

Five years or so into the summer school, Mueller was gaining experience organizing field trips, and he began to work on Ambrose to take on tours of Normandy and the Rhineland. “I told him, ‘It’s gonna change everything about how you look at history and look at World War II.’ We were about three years into this conversation, and I looked at him and said, ‘Steve, you’re afraid you’re gonna run into a German you might like.’ He said, ‘OK, I’ll do it.’ And it was an amazing experience for him and for all of us who were involved in this.”

These were high-end, two-week tours that included appearances by the likes of the sons of Eisenhower and German Gen. Erwin Rommel.

Ambrose started running into veterans, collecting their oral histories, and his friend watched as he moved away from writing presidential biographies and foreign policy books and toward D-Day and soldiers’ stories. Vets started sending him stuff like a helmet with a bullet hole in it — “I want you to have it because my kids don’t care about it.”

“His whole office was covered with parachutes and weapons and stuff.”

At this time — about 1990 — UNO administration had asked Mueller to lead development of a research park on 30 acres on Lake Pontchartrain. That’s about the spot, Ambrose told him one afternoon, he had in mind for a D-Day museum.

“He had talked for years about the fact that Congress, despite his influence with a lot of leading senators and House members, had never done anything on a museum to World War II or D-Day or anything, and he thought it was a scandal, and he told them all they ought to do something, and they all said it was a great idea but we’ll never get around to it.

“So he just said to hell with ’em — we’ll just do it right here.” On the research park land, the only sandy beach on all of the lake, the place where Andrew Higgins tested his landing craft.

Ambrose said $1 million. Mueller said four. The UNO chancellor liked the lakefront site, but business leaders who Ambrose and Mueller had formed into a board of directors wanted it downtown.

“Ten years later and 30 million later, we were downtown at the advice of our board. They were smarter than we were. We’d already designed the whole building on the lakefront.”

By 1994, they had created an Academy Award-nominated documentary and had acquired 100,000 artifacts for $300,000 from a museum in Normandy that went out of business.

They pitched their tent amid decrepit warehouses between the river and downtown; they bought one of them.

The European and Pacific campaign galleries are rich in artifacts — and in lighting, sound and wartime film that change the atmosphere around every corner. Visitors are given a “dog tag” in the form of a chip-embedded card that enables them to follow the experience of an individual war participant at listening stations. (Photo courtesy of National World War II Museum)

The senator’s blessing

After two missed deadlines for opening — and this was then just a D-Day museum — Mueller, still a vice chancellor at UNO and trying to go back to teaching, was approached with the chairmanship.

“Most of the board had resigned by this time. Everybody was giving up. They knew we had the building, but they didn’t believe we’d ever raise the money to get open. We’d never had the wisdom to hire a professional staff, which was part of the reason why we never met any goals or deadlines.

“I was kind of the last man standing. The chancellor said he’d give me 75 percent of my time to do the museum if I’d take it on for a couple years.” Mueller gradually had acquired the business, organizational and fundraising skills to do it, but he’d already sacrificed 20 years of teaching and research.

Then, on the day before the opening on the anniversary of D-Day in 2000, Sen. Ted Stevens took a private tour. He pulled Mueller and Ambrose into Mueller’s office and said, “You’ve left out my war.”

Stevens, chair of defense appropriations at the time, had served in the China-Burma-India theater. Sen. Daniel Inouye’s war, in the Mediterranean, was missing, too.

“He says, ‘Will you guys consider changing your mission and doing the whole war?’ Mueller said. “He said, ‘If you do, I’ll help.’ Steve thought we were done. He was ready to go back to his writing and be done with it. He and Stevens were friends, so he couldn’t say no.”

Stevens promised some funds from federal earmarks, and he got something else equally valuable: In 2004, Congress designated the museum the country’s official World War II museum.

“Whether it was a Honduran resort [they bought one together] or starting a summer school somewhere else in Europe to complement Innsbruck, Nick would plan budgets, cash flow, marketing,” Ambrose wrote in his memoir, three years before he died. “I would express skepticism until midway through the second drink, when it became obvious to me that Nick could pull it off, and damned if he hasn’t made it happen.”

“The board decided to make a run at it,” Mueller said. “Now, instead of talking about a 30 million-dollar museum, we’re talking 200 million.”

All the major airborne players in the war, except the B-29, hang in a separate gallery or in other parts of the museum. On a series of catwalks, visitors can get close to the planes and study their specs and roles at interactive stations. (Photo courtesy of National World War II Museum)

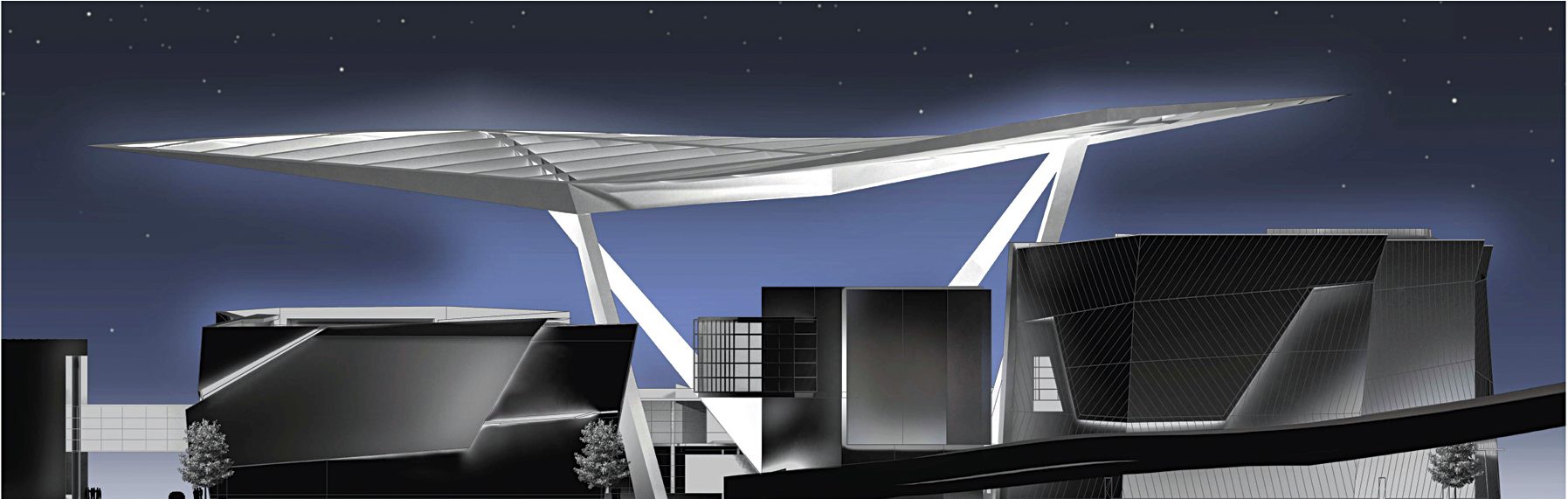

This is the architect’s vision of the finished campus, which includes a massive canopy that ties it together from a central courtyard. See the “Architectural Fly-through” video of the National World War II Museum and more images of the museum master plan and phases at alumni.unc.edu/WWII-museum. (Image courtesy of Voorsanger Architects)

And, oh yeah, Katrina

In August 2005, a year and a half after the “national” designation, it looked like the good times, as they say in the Big Easy, were rolling. That’s when the epic disaster of Hurricane Katrina rolled into town. Flood waters didn’t reach the museum. Neither, for a long time, did any people.

“This was one year after we announced a several-hundred-million-dollar campaign,” Mueller said. When the executive committee of the board met in November — in Dallas — “my job was to present them with some scenarios; do we go forward or not? There were a lot of people who said maybe we should just scrap it all. Other people said give us a plan — how are we going to get through the year, even. We got back open by the end of October. There was nobody here but National Guard.”

By then half the staff had been laid off. The choices ranged from scrap it, go back to just D-Day or to full speed ahead. Mueller recommended one of the middle scenarios: Cut out two planned buildings and proceed.

“I told them, I said look: This was important before Katrina, it’s important after Katrina. It’s even more important. Because it’s going to take a tremendous amount of strength and ingenuity and courage to go forward, and that’s what this whole museum’s about. It’s telling the story of what Americans can do when they pull together. So I said, ‘Let’s demonstrate some of the spirit that we’re trying to describe with the people in World War II.’

“I said look — it’s not Omaha Beach — nobody’s shooting at us.”

The USS Tang was the most effective submarine in the war. Though it’s impossible to portray the sub’s cramped quarters for about 30 people who see this show at one time, the video and special effects used to re-create its gut-wrenching final mission make it another must-see. (Photo courtesy of National World War II Museum)

The education mission

Like any good architecture, the museum’s exterior speaks differently to each person. While visitors last summer entered through the original old warehouse to dodge construction, the surrounding new structures are imposing, looming over the street at odd angles, evoking a fortress or warships seen from the waterline.

“The look of these buildings — the angles — everything’s off,” Mueller says of the designs of the internationally renowned Bart Voorsanger. “Everything has this kind of fractured look. That was intentional. The whole world was off balance, is what Bart would say. He wanted to show that it was fractured but yet there’s great strength and beauty in the architecture of each building.”

A visitor to the museum today traces the Allies’ European campaign and the Pacific war through artifacts and film in separate galleries, watches and feels a 50-minute “four-dimensional” film history of the war produced by Hanks and Universal Studios and gets close to warplanes and ground vehicles.

Construction is underway on a new gallery on the massive manufacturing effort and the rest of the war at home in America, designed to further underscore the sacrifice.

By next year, much of the complex will be shaded by a giant covering to be called the Canopy of Peace. Expensive? Yeah.

The museum got about $32 million from its friends in Congress before federal earmarks dried up. Louisiana gave about $75 million. The rest of the $260 million raised to date is private. That’s all capital; the museum has a $40 million operating budget and 300 employees (supplemented by 50 to 100 volunteers working on a given day).

It will need about $100 million more. The homefront exhibit under construction now is to be followed by an education and outreach wing and a new pavilion designed to examine the world the war helped create, including how the impact of the war played out elsewhere in the world.

Staring at his 77th birthday, Mueller last summer started preparing to delegate the helm. The Hall of Democracy will be his last hands-on involvement, and to him the museum is very much incomplete without the ability to reach its resources from anywhere.

Already it is training teachers from across the country, their time in New Orleans fully funded with an obligation to go back and train other teachers.

The board of directors is committed to digitizing everything in the collection — hundreds of thousands of artifacts, 8,500 oral histories, 150,000 photos — and to creating the software and content management systems to enable effortless navigation.

“We’re at an interesting time in history — we’re seeing the passing of the World War II generation,” said Kenneth Hoffman, education director for the museum, who’s been on the job since it opened. “It’s going to shift from being living history to just history. A lot of what we’re going to be doing in the future will be how to engage young people, to look for new ways for them to get into our archives. Nick is very interested in developing college-level programs.”

“We’re not trying to be a research institution,” said Mueller, who added that they have hired a senior World War II military historian and other scholars and have seven people traveling the country to gather the last available oral histories.

“We’re trying to provide access whether you’re coming here as a visitor or you’re in Dubuque or Denver or Portland, Maine, and you want access to the best knowledge and information. We’re at a pivot point from trying to be the best museum on World War II in the world to being the best source of knowledge and information on World War II in the world.”

Remaining relevant

Life seemed pretty good for Mueller as he prepared to escape the oppressive New Orleans summer for a month at his cabin in the North Carolina mountains.

He got a crown of sorts in May when, along with Hanks and Brokaw, he received the French Legion of Honor. The medal, created by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1802, is the French government’s highest honor. It brought to mind Steve Ambrose’s tours of the country that germinated the idea for the museum.

Mueller’s goal now is to finally get to teach in the European summer school whose faculty he was too busy building to join. Once he’s detached from the museum, those who come after will wrestle with keeping the war relevant. It’s been easy up until now. He sees veterans coming in with their children and grandchildren, many of whom — given the way the war played out on many fronts — knew they were among the random lucky to come back. They might not have talked about it much at home. Here somebody else does the talking.

“They don’t have to carry the burden of the story,” Mueller said. “We do that.”

David E. Brown ’75 is senior associate editor of the Review.

Explore the National World War II Museum

via its extensive website.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.