University Day With Andy Griffith

Posted on Sept. 26, 2012by Jim Hughes

Forgotten in all the coverage of the passing of Andy Griffith ’49 in July was a performance I consider one of his finest and most unforgettable, when he was just playing himself.

The occasion was University Day, Oct. 12, 1978, and Griffith had come home to Chapel Hill to receive the Distinguished Alumnus Award and deliver the traditional University Day address. It’s safe to say there hasn’t been one like it before or since.

I was in the back row of Memorial Hall, covering the event for the old Chapel Hill Newspaper. It was a little after 10 that morning when Andy took the dais, stood there a moment to soak up the applause, beamed that unmistakable Andy Taylor smile and addressed the overflow crowd with his signature Andy Taylor line:

“I ‘preciate it,” he said. The audience roared. “Who says you can’t come home again?”

And then he dove into a 15- or 20-minute monologue, consisting entirely of old jokes and stories, one right after the other, tired old chestnuts that were already on life support when Old East was new, old cornpone stories he said he’d borrowed from George Lindsay, who played Goober on The Andy Griffith Show and was by then a regular on Hee Haw, the country humor TV show.

He told the one about the Avenging Truck Driver: “There’s this truck driver. Out on the highway. Goes into a cafe and orders the blue-plate special. And these three Hell’s Angels come in and eat up his meal: steak, eggs, coffee, everything. The truck driver doesn’t say anything, gets up, pays the check and walks out. Hell’s Angel says to the waitress: ‘That ain’t much of a man there is it?’ And the waitress says: ‘Yeah, and he ain’t much of a truck driver either. He just ran over three motorcycles.’ ”

He told the one about the Half-Bright Watermelon Salesmen: “These two old boys, wanted to make some money, so they bought up a load of watermelons. Paid 50 cents apiece for ‘em. Took ‘em downtown and sold ‘em two for a dollar. And when they got through they was counting up their money and one old boy says, ‘We ain’t got no more money than we had before.’ And the other one says: ‘I told you we weren’t gonna make no money until we got ourselves a bigger truck.’ ”

He told the one about the Old Lady and the Train Robbery: “This old lady’s on a train headed west and bandits stop the train and make everybody climb out. And one of the bandits calls to the old lady: ‘Give us your money, lady.’ ‘Don’t have any,’ she says. ‘C’mon, lady, don’t make me search you.’ And she says, ‘I don’t have any money.’ And so the bandit frisks her all over, up and down her whole body, and says, ‘All right, lady, where’d you hide it?’ And she says, ‘I told you, I don’t have any money, but if you’ll do that again, I’ll write you a check.’ ”

He went on in that vein for another few minutes, but I had stopped taking notes and had focused on the audience. The hall was packed with professors and deans and doctors and assorted University bigwigs, a group as solemn and serious and loaded-up-with-learning as you’d ever want to meet, decked out in their finest academic regalia — caps and gowns and brightly colored sashes — and after the second or third joke he had them all in the palm of his hand. They were completely out of control, rolling and rollicking and giggling like school kids, slapping their knees and their neighbor’s backs and generally comporting themselves with the same aplomb and sophistication as the front row of the Blue Collar Comedy Tour.

Then, with perfect timing, the jokes stopped and Andy turned serious. “I want to tell you something,” he said. The room grew silent. “As we were walking up the lane here to this wonderful hall, I don’t know about you, but I was moved. It was all I could do to fight back tears. And the reason was I knew I was going to walk up on this stage, and this is the stage where the first time in my life I was ever in a play.

“I have to tell you something. It’s very, very moving. This is a special place. I haven’t been back here that much. Not much at all.” His voice broke, but he managed to pull it back together. “I guess the last time was when I did that monologue out on the football field, and that was a right good while ago.” The big grin came back on his face. “Guess what it was.”

He seemed to gather speed, as if to hasten his exit from the stage. He spoke briefly about what the University meant to him and the lessons he’d learned from a few favorite professors and then remembered and thanked a short list of people who helped start him on his way. The last of these was my boss, Orville Campbell ’42, owner and publisher of The Newspaper.

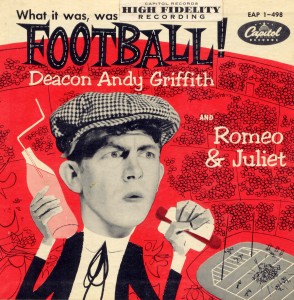

Campbell’s role in Andy’s career has been largely unreported, but I can tell you it was a major one. Campbell was among the first to see the potential of some of Andy’s routines, like What It Was, Was Football and his countrified version of Romeo and Juliet. In 1953, he signed Andy to his Chapel Hill-based Colonial Records label and cut an LP. Within a year, Capitol Records bought the rights and took the record national. Shortly after that, Andy did What It Was, Was Football on the Ed Sullivan Show — the highest rated TV show in the country — and his career took off from there.

Campbell came up to me at my desk the next morning after my story ran. He was in an expansive mood. I wish I’d written the whole conversation down. But I remember he told me the record went gold in less than a year, and his first royalty check was for something like $200,000 — an immense sum back in the early 1950s.

I’ll never forget what he said after that: “I took that check and went down to my banker and everybody else I owed money to and I told ‘em all they could kiss my ass.”

Jim Hughes ’70 of Raleigh is a senior editor at Metro Magazine, where portions of this story originally appeared.

More online…

- Andy Griffith, Favorite Son of All Tar Heels, Dies at 86

News report from July 2012 - Carolina alumni share their thoughts on the GAA’s Facebook page following the death of Andy Griffith in July 2012

- Fanfare for the Uncommon: Carolina has dressed up Memorial Hall as its ambassador for a daring performing arts venture. Andy Griffith ’49, Richard Adler ’43 and Maxine Swalin are the first recipients of the inaugural Carolina Performing Arts Lifetime Achievement Awards. From the November/December 2005 issue of the Carolina Alumni Review.

- News article about Griffith’s University Day appearance, from the October 1978 University Report.