We Go Back a Ways

Tim Sullivan ’85 wants you to discover who you are, where you came from and how you fit into the whole human family.

by Sandra Millers Younger ’75

Sometimes ignorance is bliss. Before I discovered Ancestry, I felt totally justified rolling my eyes at my husband’s outlandish claim that his family had descended from the legendary Indian princess Pocahontas.

“That’s ridiculous,” I’d tell him whenever the subject came up.

He’d shrug. “Mom says it’s true.”

“I don’t care what your mother says. You are not related to Pocahontas.”

Finally, I decided to find out once and for all. Late one night, after my husband had gone to bed, I logged into Ancestry.com and started building his family tree. It was easy really. All I had to do was enter the names I knew, and hints popped up suggesting more names, from previous generations.

Pretty soon I was back in colonial times. Just a few more clicks took me all the way to the early 1600s. And suddenly there they were, the “it” couple of Jamestown, Va. — English colonist John Thomas Rolfe and Princess Pocahontas Matoaka “Rebecca” Powhatan.

I couldn’t believe it. The family story I’d scoffed at for decades was true. And I owed the 10th-great-grandson of Pocahontas an apology.

Tim Sullivan ’85 can’t get enough of stories like this. During his 10-year tenure as CEO of Ancestry, the company has grown into a global corporation valued at $1.6 billion and “guided by a very human and personal mission: to help people understand who they are and where they come from.”

Anecdotes from Ancestry’s users document the priceless value of piecing together family puzzles. Imagine finding a portrait of the mother you never knew because stricter times forced unmarried women to give up their babies. Or a ship manifest documenting your great-grandparents’ arrival on Ellis Island. Maybe the names of long-lost aunts, uncles or cousins, written in swirly longhand on the faded pages of 100-year-old census rosters.

It doesn’t seem far-fetched to suggest that such fundamental discoveries could change the way people think about themselves, their family members, perhaps even the world.

While maximizing Ancestry.com’s business potential, Sullivan and a dedicated global team also are asking big questions about human potential, past and present. What can we learn from the lives of those who came before us? What might be possible if we all understood more clearly how we fit into the universal and timeless human family?

“We try to have a bold vision and modest aspirations,” Sullivan said. “We believe there can be much social benefit by people understanding they really are part of something larger than their immediate family.”

Measuring discoveries

Like any well-run company, Ancestry.com tracks its numbers, and the numbers are impressive:

- The world’s largest online community of family history enthusiasts, Ancestry hosts more than 60 million user-generated family trees, containing more than 6 billion profiles, plus 200 million photographs, scanned documents and stories.

- More than 2 million Ancestry.com subscribers also pull from the company’s ever-growing acquisitions of historical documents — 15 billion digitized and indexed records ranging from U.S. census reports to Chinese temple rolls.

- The company employs more than 1,400 people globally, 1,000 of them at the corporate headquarters in Provo, Utah; next year, the business plans to move into a new $35 million campus under construction closer to Salt Lake City.

- All this activity and growth boosted company revenues from $225 million in 2009 to $620 million in 2014.

But Ancestry tracks another metric unique to its mission: Sullivan calls it “moments of discovery.”

“Yes, we measure page views and revenue and profitability and all those things,” he said, “but we also measure discoveries. We ask: How many discoveries per subscriber have we delivered this month? And that’s ultimately a value proposition” that attracts customers.

Sullivan is quick to credit previous generations of Ancestry leadership with transforming the company from its 1983 origins, as a small publisher of genealogical books and newsletters, into a major online repository of historical records.

Ancestry employs more than 1,400 people globally, 1,000 of them at the corporate headquarters in Provo, Utah. They plan to move into a $35 million campus under construction closer to Salt Lake City.

But there’s no question he’s made his mark over the past decade. Since Sullivan’s 2005 arrival at Ancestry’s current headquarters in picturesque Provo, a leafy contemporary campus snugged up against the magnificent Wasatch Mountains, both the company and global interest in online family history research have exploded.

Once the narrowly defined province of professional genealogists and amateur family historians — think Aunt Ruth, keeper of the family Bible, or Cousin Larry with his shoebox full of faded snapshots — the pursuit of family stories has gone mainstream, a phenomenon made possible by the Internet and related technological advances.

“By investing in technology, we’ve found ways to make something that was incredibly hard and difficult massively easier,” Sullivan said. “And that has expanded the universe of people who might someday find it interesting to spend a few hours on the Web researching their family history.”

To serve these curious family detectives, Ancestry has amassed a prodigious online library of acquired digitized records while creating a robust social network that encourages users to share information gleaned from personal family records and photographs. Powerful proprietary search tools help subscribers sift through towering haystacks of data to find specific bits of information.

Ancestry’s partnerships with private and government archives in the U.S. and abroad have yielded unprecedented access to musty, sometimes disintegrating stacks of records, logbooks and microfilm, which Ancestry scans, indexes and stores safely for posterity in massive databases measured in petabytes (1 petabyte = 1,000,000 gigabytes). These efforts continue to pick up steam as Ancestry expands internationally. Thirty percent of subscribers now log in from outside the U.S.

The company’s trove of family stories also has grown through acquisitions of firms with complementary databases, such as Archives.com, Fold3, FindaGrave.com and RootsWeb. Last year, Ancestry partnered with FamilySearch, keeper of the official Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints genealogy database, containing 1 billion records from 67 countries.

To broaden interest in exploring this unprecedented compilation of family history resources, the company has sponsored a number of relevant television programs, including Finding Your Roots on PBS and Who Do You Think You Are? on The Learning Channel. And you’ve no doubt seen a few of their tantalizing online ads: “George Clooney related to Abraham Lincoln!” for instance.

In late 2012, Ancestry.com launched Newspapers.com, a powerful site optimized to display old newspapers dating from the late 1700s in an easy-to-read, easy-to-search format. Filters and thumbnails help users quickly sort through millions of newspaper pages — and highlight, clip, print, download or save.

A major addition to Ancestry’s suite of companies, Newspapers.com has unlocked a vast and historically rich resource previously available only in dusty library stacks and basement “morgues,” where newspaper companies file their own past issues.

New methods of ancestry research rely on a lot of manual work, including microfilm scanning and page-by-page data entry of scrapbooks.

In less than three years, the site has grown from 25 million to nearly 100 million pages. By partnering with repositories of these old papers — including UNC — Newspapers continues to aggressively expand its database, adding millions of newly digitized pages each month.

Since early 2013, Newspapers has digitized 2,700 reels of Wilson Library’s microfilmed newspaper records, totaling 2.5 million pages. The next step is to pursue permission to add pages published after 1922, which are not yet in the public domain and may be protected by copyright.

Meanwhile, in San Francisco, a world-class team of scientists is tackling the mysteries of family history with different tools. AncestryDNA offers low-cost, leading-edge DNA testing capable of pinpointing an individual’s ethnic and geographic origins.

“That’s the new thing we’re doing, and it’s kind of exciting,” Sullivan said. “People who have never been able to research anything about their family tree, we’re going to be able to start telling them amazing things about their ancestors. We’re going to connect them to third or fourth or fifth cousins who have researched those ancestors, and they’re going to meet some of those people.

“It’s almost like we’re defining tribes for people,” he continued. “Today, people have hundreds, and soon they’ll have thousands, of genetic cousins they can connect with.”

More than 700,000 people have taken the AncestryDNA test, and Sullivan envisions a database of tens of millions. “It’s such early days for the DNA test.”

A student entrepreneur

Sullivan’s personal story began in Loudonville, N.Y., a tiny town near Albany. His horizon began to broaden when he followed his older brother to The Hotchkiss School, a boarding school in Connecticut. As a senior at Hotchkiss, Tim was nominated for a Morehead Scholarship, and he turned down Harvard to accept it.

When Sullivan arrived as a freshman in fall 1981, he had every intention of becoming a doctor like his father. But on the advice of a former Loudonville neighbor, Dr. Stuart Bondurant ’50, who had become dean of UNC’s School of Medicine, Sullivan spent his four years on campus exploring far beyond premed courses.

Bondurant’s suggestion: Create the best possible educational experience by seeking out the best teachers on campus, regardless of subject matter. “That’s a pretty powerful lesson to begin to learn as a freshman in college,” Sullivan said, “that it isn’t all handed to you, that you’ve got to be a student entrepreneur.”

By his sophomore year, Sullivan had pivoted to liberal arts, especially interdisciplinary and “creatively classified” courses. He ended up majoring in political science and never took a single business course.

Sullivan’s Carolina experiences also introduced him to media, sparking an interest that governed his eventual career choices. He co-founded the University’s student-run television station and went on to co-produce the Morehead Foundation’s first promotional video.

Clearly Sullivan took Bondurant’s advice to heart and squeezed the juice out of his Chapel Hill experience.

And: “It was where I met Jane. That’s at the top of my list.”

Kinston native Jane Bowen ’86 and Sullivan married soon after graduation and settled in the Triangle for a few years. Jane taught school, while Tim joined three other Carolina grads in starting a corporate video company.

To his surprise, Sullivan discovered that he loved the back-end tasks of running and growing the business even more than shooting video and writing scripts. It was enough to propel him toward business school. This time, he said yes to Harvard and emerged two years later with an MBA.

A cultural shift

Still interested in media, Sullivan landed a job with Disney — in Hong Kong. It was a long way from Loudonville, but leaving the Northeast for North Carolina had whetted a lifelong appetite for adventure, which Jane shared. Over the next few years, the couple had two children, and Tim advanced to managing director of the Asia Pacific region for Disney Home Entertainment.

In the meantime, the media landscape was changing.

“When I graduated from Carolina in 1985, there was no Internet,” Sullivan said, “but by 1999, there was an Internet, and it was starting to really appear to be a game changer.”

Eager to explore the new media, he took a job in Los Angeles with a small online company soon to become known as Ticketmaster. Looking back, Sullivan sees his departure from Disney as a leap of faith.

“I think I had two people working for me on day one of the new job, and I didn’t really know what I was doing.” He learned fast. After only a year, Ticketmaster acquired an Internet dating site, and the Sullivans moved to Dallas, where Tim became COO and, a year later, CEO of Match.com.

It’s almost hard to believe, now that online dating has become ubiquitous, but only 15 years ago it seemed like a sketchy, even dangerous way to meet potential romantic partners. Sullivan helped engineer a cultural shift in the way couples find each other.

“It was very disruptive. We were creating a new behavior.”

Sullivan knew the success of Match.com would depend on “doing two things exceptionally well” — building a product that really could match people based on their interests, and destigmatizing the idea of meeting prospective dates online.

“So we focused on spending dollars in clean, bright places like television, to help impart that sense of legitimacy to the category. That was the intent, and it was a very effective strategy. Little by little, people began thinking of online dating as a natural thing to do. Once that stigma was removed, the business just took off.”

Sullivan looks back on all he’s accomplished with gratitude and humility. It’s a deep, centering perspective he nurtures during his daily commute, a scenic hourlong drive from his home high in the mountains near the resort village of Park City down through stunning forested canyons and meadows to his office in the valley far below.

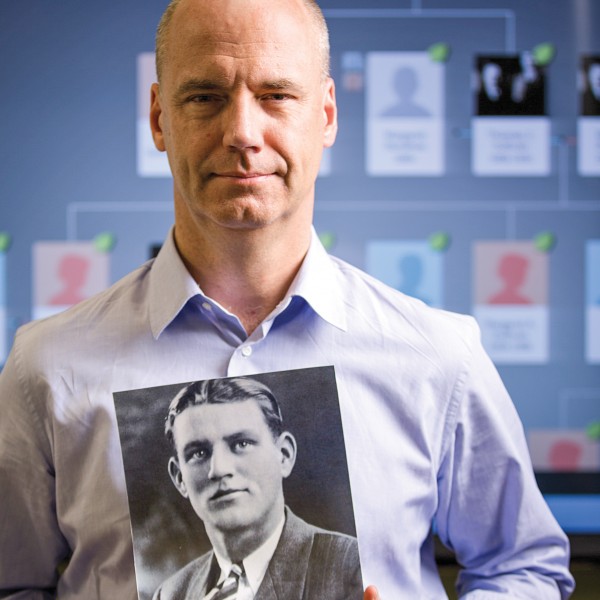

His grandfather — in the black-and-white photo — was an electrician; his dad was a doctor. When Sullivan came to UNC, he thought he’d study medicine, too, but he pivoted to liberal arts.

He’s happiest about having found a way to balance his success between career and family. With their daughter, Lindsey, who just finished her sophomore year at Carolina, and their son, Thomas, following the family tradition at Hotchkiss, Tim and Jane are living into a new chapter of their own family story.

“We are adjusting to the reality of having no kids at home,” Sullivan said. “We have a chocolate lab and a Great Dane puppy that are trying to fill the space.”

But the Sullivans also are enjoying the chance to spend more time in North Carolina again now that Lindsey’s there. Tim’s seat on the Morehead-Cain Foundation Scholarship Fund board also takes him back to Chapel Hill.

Partnerships and potential

Ancestry also is involved with UNC through two research projects managed by University entities. The company commissioned and funded a study by the Odum Institute, completed in November, that found that family history enthusiasts are significantly more likely to engage in volunteer work, civic activities and charitable giving.

In addition, Ancestry is partnering with the School of Education’s Learn NC program to give K-12 teachers classroom access to its databases. The idea is to pique students’ interest in history by enabling them to discover their own family stories.

“We would just love for Ancestry.com to be a tool educators could leverage,” Sullivan said.

His corporate agenda also calls for continuing the company’s global expansion, enhancing the user experience to make family history research more fun for more people, and, perhaps most important, growing AncestryDNA into “the largest personal genomics company on the planet.”

“I have loved working for Disney, where you’re delivering emotional magic through your entertainment products, and working for Match.com, where you’re truly helping people find their soul mates. But I frankly can’t imagine doing anything else that has the potential Ancestry still has after my nine years here.

“The bigger it gets,” he believes, “the more everyone will understand how they fit into this picture of humanity.”

Sandra Millers Younger ’75 is a writer in Lakeside, Calif., and founder of and master story strategist at Strategic Story Solutions.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.