What Is in a Name

Posted on March 11, 2015

Students demanding a name change for Saunders Hall used their voices, signs and symbolic nooses in a demonstration in front of the building on the Monday morning following the Jan. 30 rally. They had the support of 84 faculty and graduate students who work in Saunders. (Photo by Claire Hannah Collins/DTH)

In advance of a trustees report, students of color spill their anger about enduring honors to white supremacists.

They have a new name for Saunders Hall.

Nowhere is it required or even suggested that you find a cause and speak up about it, that you stand close to where Davie and his band picnicked and said, yeah, this is the spot, and say, “Yeah, this is my spot, too,” and yell out your anguish. It is perfectly acceptable to study, to inquire and prepare, to befriend and be quiet for four years. To demand is merely an option.

While hearing may not be a choice — what with banners and press coverage — listening is another option. A gathering of 100 or so people, joined by another 50 who have marched from the Pit for dramatic effect, can see all the groups of three or four keeping their distance, taking little detours on their way to lunch on Franklin.

On the next-to-last day of January, members of the Real Silent Sam Coalition blocked a chilly wind with 20 yards’ worth of bed sheet that read, “Can You Hear Us Now?” Because, they said, the trustees and South Building and not-of-color Carolina either hasn’t heard or hasn’t listened.

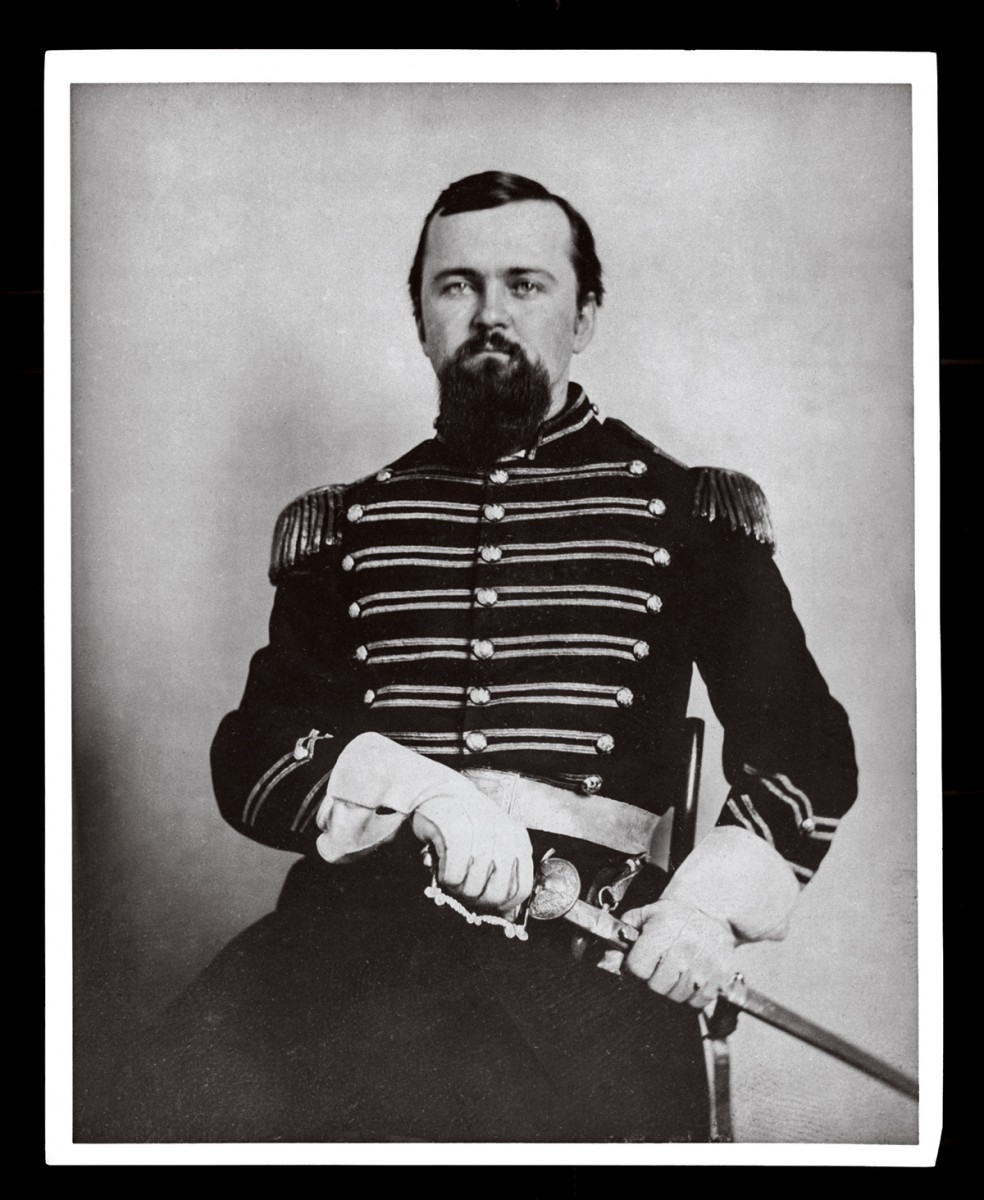

Williams Saunders (class of 1854) (Photo courtesy of the North Carolina Collection)

They had three demands: that freshman orientation include “material addressing the history of racialized violence on campus”; that the monument to UNC’s Confederate war soldiers don a plaque “explaining how it commemorates a history of white supremacy”; and that the name William Saunders (class of 1854) be taken off the building that houses the departments of geography and religious studies and be replaced with one that has positive meaning to black students who say this is the wrong kind of remembrance for the leader of the Ku Klux Klan in North Carolina. [The trustees are expected to discuss the issue at their March meeting.]

Historically, this is a tough sell. The argument that to cover over the past is to be doomed to repeat it is powerful. Better to keep poignant symbols for succeeding generations — as Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist Edwin Yoder ’56 wrote in a letter to The Daily Tar Heel, “in the recognition that we too are imperfect beings with faults of which we may not be aware.”

Yoder also wrote this, familiar where Saunders is concerned: We don’t have concrete proof that Saunders was a leader, even a member, of the Klan. Even if he was, he was a man of his time, many say, and his time — Reconstruction — brought waves of shock to the status quo.

Men and women of the current time — rocked by Ferguson, by brazen ugliness on certain social media, by what they perceive as a racist tilt to the scandal involving UNC’s former African and Afro-American studies department — say that “white supremacy knows no time.”

Saunders Hall

‘Second-class status’

“We absolutely refuse to be complacent about these issues any longer,” said Erika Baker, a senior who spoke for the Real Silent Sam Coalition. For several years, the group has cut Sam a break, insisting on some additional language for the soldiers’ memorial that includes the perspective of people of today, who could have been slaves during the war, could have labored under Jim Crow when the statue was erected. But they have backed off a demand that it be taken away, turning their attention to what the University considers a high honor — a building naming — and what they see as an insult without nuance.

At a smaller rally at Saunders three days later, sophomore Charity Lackey wore a symbolic noose around her neck and said, “This is what Saunders would do to me.”

Shock value aside, this time the group portrayed its grievance in a broader context. Some members spoke of being marginalized at UNC, of serving as statistics kept in back pockets to show how diverse the University is while they get the cold shoulder and feel like less than full participants in the Carolina experience.

“The stigma of my second-class status has not been erased from this campus,” said Ashley Winkfield ’14.

Eighty-four faculty members and graduate students who work in Saunders Hall are behind the effort to rename.

The University has confronted its racial past before, such as when it removed the name of Cornelia Phillips Spencer from an award for women after closer scrutiny of her public writings revealed that she acted against the interests of black people in the campaign to reopen the University in 1875.

But Carolina never has taken a person’s name off a building for nefarious behavior.

Duke University quietly erased the name of Charles Aycock (class of 1880) from a campus building last June. Remembered as the “education governor,” Aycock supported schooling for blacks as well as whites, but he also said rather revealingly in a public speech in 1904: “Let us cast away all fear of rivalry with the negro, all apprehension that he shall ever overtake us in the race of life. We are the thoroughbreds and should have no fear of winning the race against a commoner stock.”

East Carolina University’s trustees agreed in February to take Aycock’s name off a campus dorm. ECU plans to create a space elsewhere on campus where figures from its past, including Aycock, will be recognized and their personal histories explained.

With the focus on Saunders, Aycock dorm at Chapel Hill may be off the hook for now, but Aycock’s is one of 10 names — all of them on campus building nameplates — identified by the UNC Library’s Virtual Museum of University History as having ties to white supremacy.

The unexpected classmate

Novelist Zora Neale Hurston attended a playwriting seminar at UNC in early 1940. (Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Zora Neale Hurston, who was born in the racially turbulent late 1800s and died on the eve of the civil rights movement, authored four novels — including the acclaimed Their Eyes Were Watching God in 1937.

Hurston studied at Howard University, where she founded the student newspaper; Barnard College, where she was the lone black student; and Columbia University.

And at Carolina, too, very briefly, where in 1940 she would have been shown the back side of the door if her attendance hadn’t been kept on the down-low.

In 1939, she found herself invited to the present-day N.C. Central University in Durham to start a drama department.

In January 1940, she made her way to Chapel Hill to give a talk to an arts group on the subject of creating a Negro folk theater. That was no secret, covered by The DTH and other newspapers. By those accounts, it was a lively evening. Hurston’s biographer, Valerie Boyd, wrote: “In a wide-ranging and animated talk, Hurston ridiculed the white man’s idea of good food, discussed the Negro’s love of drama, and contrasted black and white attitudes toward religion.” Boyd quoted her as saying, “You have a mistaken idea that we’re more religious than you … we’re more ceremonial than you. We’re not half as scared of God as you.”

Paul Green ’21, UNC’s stage giant, was there. He immediately invited Hurston to sit in on his playwriting seminar. She said, “I think that is one of the most pleasant things that has ever happened to me, and I think I’ll benefit by it.”

One student in the class called her the star of it. Another made it clear she didn’t want Hurston, because of her race, in her class. Green told the complaining student: “We’re certainly going to miss you.”

Hurston left the Durham school in March; she and Green continued to talk excitedly about collaborating on a play, but it never happened.

The Real Silent Sam Coalition has put forth Hurston’s name as a replacement for Saunders’. (Five buildings on the campus carry the names of African-Americans: The Kennon Cheek/Rebecca Clark Building, once the University laundry and now headquarters of UNC’s housekeepers, honors workers advocacy organizer Cheek and longtime Chapel Hill-Carrboro community activist Clark. One of the newer South Campus dorms is named for George Moses Horton, a Chatham County slave who visited the campus and sold poems to the students for use with their sweethearts and who later authored the first book published by a black man in the South. The undergraduate admissions office, originally Navy Hall and then the Monogram Club, was renamed for Roberta and Blyden Jackson, the first tenured black faculty members. The University’s Center for Black Culture and History bears the name of beloved faculty member and adviser to the Black Student Movement Sonja Haynes Stone. John Turner, former dean of the School of Social Work, is honored on the school’s Tate-Turner-Kuralt Building.)

In apparent reference to Saunders’ appearance before a congressional committee investigating the Ku Klux Klan, the words “I DECLINE TO ANSWER” are chiseled on his tombstone. (Photo by Adam Jennings)

‘I decline to answer’

Born in 1835, William L. Saunders entered UNC in 1850, graduated with honors four years later, and earned his law degree in 1858. He volunteered for war service in 1861 and rose to the rank of captain, then major, then colonel.

The woman he married in 1864, Lucy Martin Plummer, died a year later, and Saunders never married again. He became interested in public affairs in the late 1860s. Later, he was chief clerk of the state Senate and edited newspapers in Wilmington and Raleigh. He was secretary of state from 1879 to 1891, during which time he gained renown as a historian, producing 30 volumes on North Carolina’s colonial and early state periods.

Collier Cobb (class of 1882) taught geology at the University for 41 years, and he became a big William Saunders fan. In a glowing biography in the University Magazine in 1907, Cobb wrote: “Toward the close of the Reconstruction period, when Colonel Saunders was doing so much to rescue the state from the ruin and degradation that threatened her, he was sought by the United States authorities, as he was said to be the Emperor of the Invisible Empire, another name for the Ku Klux Klan.”

Saunders took off fishing to contemplate his anticipated arrest. A friend found him and told him that some people had raised enough money for him to flee to Europe. But he faced the arrest and was taken to Washington to appear before Congress’ Joint Select Committee on the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States.

While in town to testify, Saunders stayed in the home of Alfred Moore Waddell, a congressman from North Carolina. (Waddell is noted as one of the principal architects of the Wilmington race riot of 1898, in which a mob of whites burned a black-owned newspaper, killed an undetermined number of blacks and drove thousands more out of the town. Waddell was subsequently elected mayor after he threatened to “choke the current of the Cape Fear River” with black bodies.)

By Waddell’s account, Saunders was asked “hundreds of questions.” His reply to all of them is chiseled at the bottom of his tombstone in a churchyard in Tarboro: “I decline to answer.”

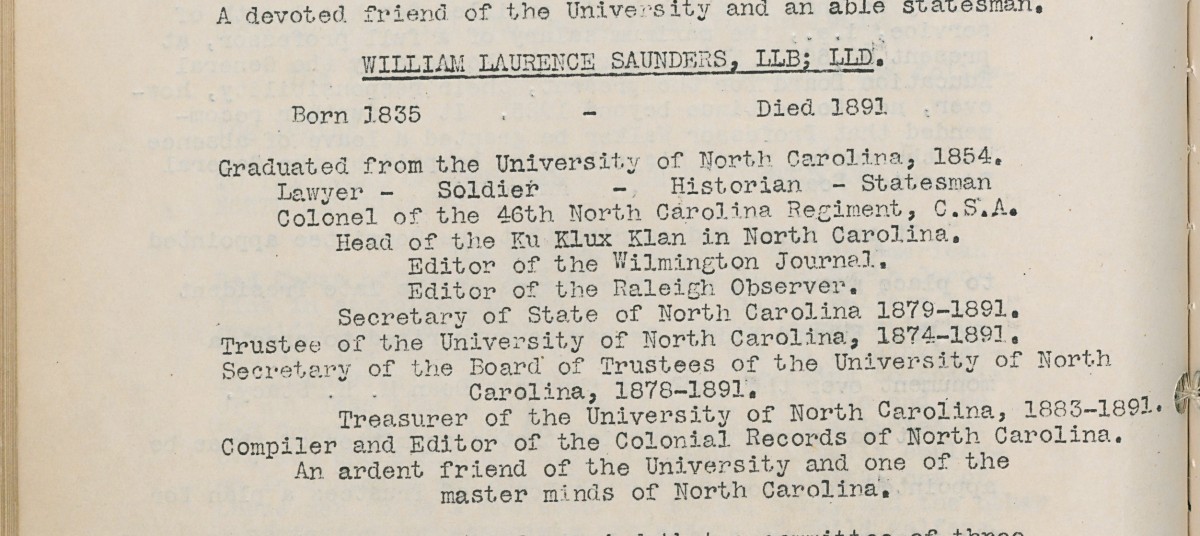

Some people aren’t satisfied there’s enough evidence that Saunders was the Klan leader. But the trustees accorded him the building name in the face of a biography printed in their meeting minutes that said he was. (Courtesy of Wilson Libary)

Waddell would address the Alumni Association on “The Life and Character of William L. Saunders” one year after Saunders’ death in 1891, in which Waddell said Saunders was a man “who knew how to guard his secrets and protect his honor.”

Waddell went on: “He loved the grey walls of these old buildings, and the refreshing shade of these magnificent oaks with an hereditary as well as with a personal affection, and in the evil days that followed the war the silence and desolation which reigned here grieved him sorely, and stimulated him to the task of restoring the University to her ancient prestige.”

Saunders was a University trustee from 1875 until he died. He received an honorary degree in 1889; he also held master’s and law degrees from UNC.

In 1920, the trustees approved naming a residence hall for Walter Leak Steele (class of 1844) and another for Saunders, but after Steele dorm was built, funding fell temporarily short, and Saunders’ name was put on the classroom building a few yards south of Steele on the University’s second major quadrangle.

As to whatever else Saunders did with his time, he played things closer to the vest than did Spencer or Aycock or Alfred Waddell; if he rode in the night in a hooded robe, he didn’t boast about it. Yoder in his recent letter echoed others over the years: “Saunders’ relationship with the KKK rests on hearsay, and shaky hearsay at that.”

But one fact is not in dispute. When the trustees approved naming a building for him, the biographic sketch committed to the meeting minutes read in part, “Head of the Ku Klux Klan in North Carolina.”

— David E. Brown ’75

In addition to Saunders, Aycock and Spencer, the UNC library’s Virtual Museum of University History identifies seven people for whom buildings on the campus are named as having ties to white supremacy. They are Julian Shakespeare Carr (class of 1866), Josephus Daniels (1885), John Washington Graham (1857), J.G. de Roulhac Hamilton (1932), Cameron Morrison, John J. Parker (class of 1907) and Thomas Ruffin. View details on these people at museum.unc.edu/exhibits/names.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.