A Soldier’s Story

Posted on Nov. 8, 2018

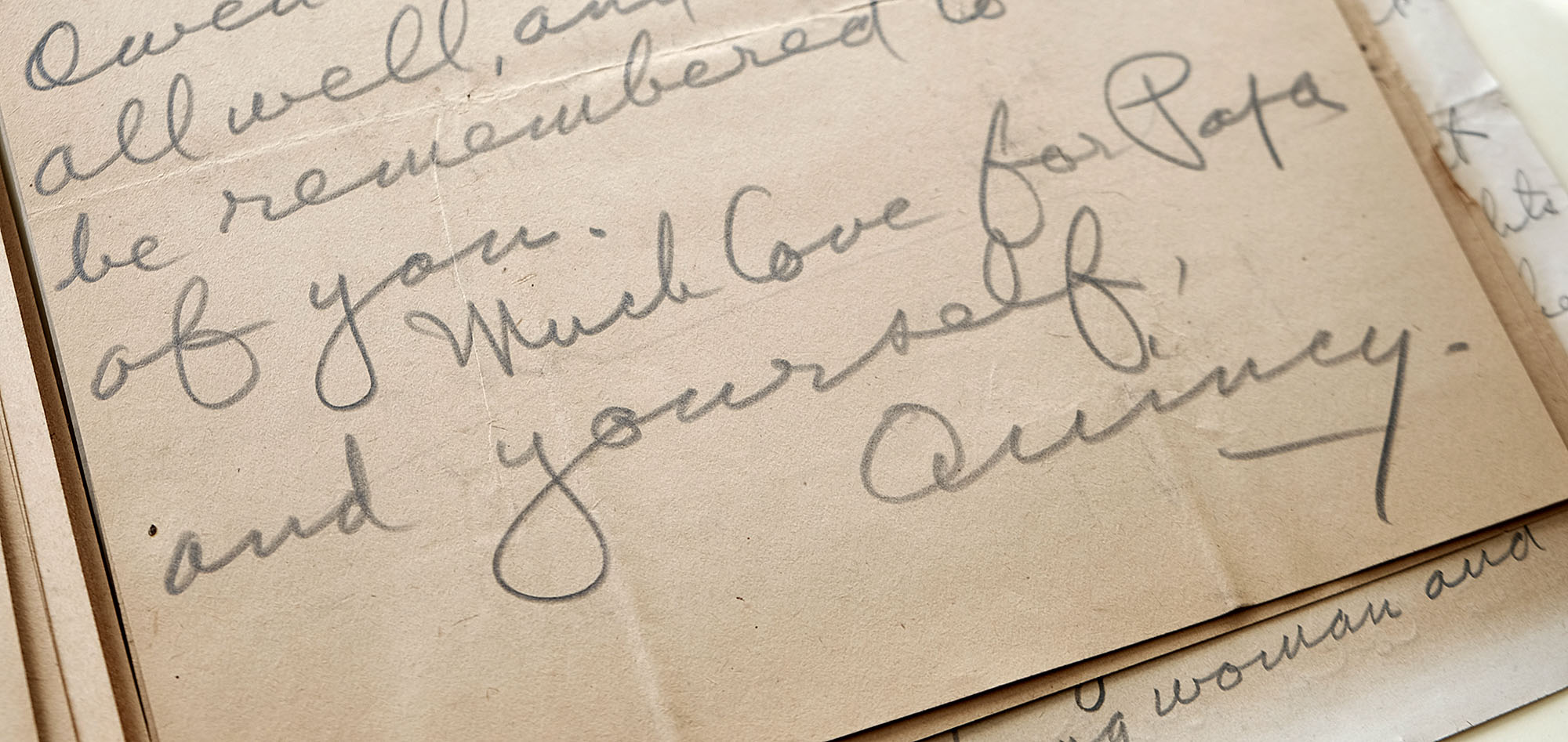

Letters written by Quincy Sharpe Mills (class of 1907) during World War I. (Photo by Grant Halverson ’93)

How opening a box of letters, photographs and journals, long housed in Wilson Library, has connected two alumni from across a century.

by Jeffrey R. Hoffman ’78

As a journalism student at UNC, Jeffrey R. Hoffman ’78 received the Quincy Sharpe Mills Memorial Scholarship one semester. At the time, the name attached to the award — a Statesville native and member of the class of 1907 — meant little to Hoffman. Decades later, curiosity led him to Wilson Library, revealing a journalist of such conviction that, in urging his newspaper readers to serve in what was then called The Great War, he heeded his own call.

As the world marks the 100th anniversary of the end of what we now call World War I — Nov. 11, commemorated in the U.S. as Veterans Day — Hoffman reflects on what Mills saw as his duty to defend democracy.

Words and War

A conservator at the Southern Historical Collection handed over a box of materials that essentially summed up the life of a man I never met but whose life had a great impact on my own. The personal letters and journals, sentimental objects, photographs and books provided intimate insight not only to who that person was but also how others loved and cherished him.

Connecting those artifacts and drawing upon a biography written in 1923 reveal the bravery of a fellow alumnus on a European battlefield in The Great War and the personal sense of service that led him there.

A chance connection

My first encounter with Quincy Sharpe Mills (class of 1907) was as a first-generation student at UNC’s School of Journalism (now School of Media and Journalism) when I received a much-needed scholarship bearing his name. Years later, a chance donation I made back to the Quincy Sharpe Mills Memorial Scholarship opened the doors that led me to the Southern Historical Collection, where I learned how the ordinary can lead to the profound.

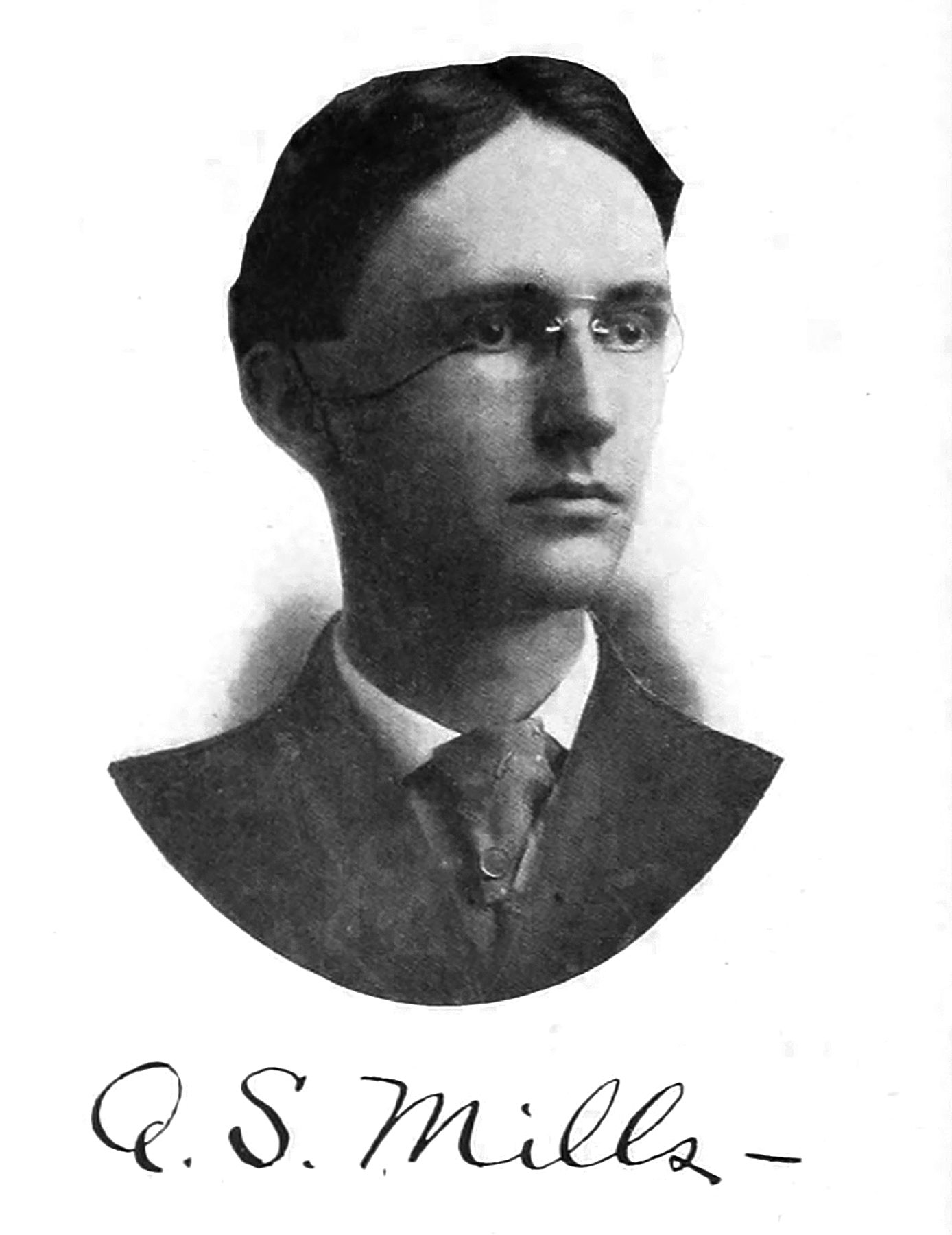

Portrait of Mills from the 1907 Yackety Yack.

Just how he came to be on a battlefield in France is deeply wrapped in Quincy Mills’ patriotic Scotch-Irish roots, his keenly developed sense of service and in the political and moral struggle the U.S. had about its role in the world 100 years ago.

The only child of Nannie Sharpe and Thomas Mills, Quincy heard countless stories about his ancestors. He knew of Capt. John Mills of the Continental Army, who with Gen. Nathaniel Greene chased Cornwallis from Cowpens to Guilford Courthouse. And of William Sharpe, a member of two North Carolina congresses in 1775 and 1776, when the state’s constitution was adopted. And of family members’ participation in the Civil War, the Spanish-American War and in North Carolina’s political and civic life.

Mills carried that spirit of service to his student days at UNC, being active in a number of clubs and associations, including the Dialectic Society — the literary and debate organization that remains the University’s oldest student organization. He also exhibited his love of journalism, serving as editor of Yackety Yack and editor-in-chief of The Tar Heel while also writing for The Charlotte Observer.

Degree in hand, he left North Carolina for New York in 1907, landing a job as a reporter for The Evening Sun, the afternoon cousin of The Sun, best known for its 1897 editorial response to a young girl asking if Santa Claus was real.

A call to arms

Rising rapidly, Mills covered politics at the local, state and national levels, becoming friends with John Purroy Mitchel, who was the city’s youngest mayor, elected at age 34, and with Theodore Roosevelt, who after his presidency remained a force in national politics. Roosevelt often was the target of Mills’ barbs in his editorials for The Sun, but Roosevelt’s strong endorsement of the Allies’ war efforts and his dislike for President Woodrow Wilson found frequent support from Mills’ typewriter.

RELATED COVERAGE

RELATED COVERAGE

Lt. Quincy Sharpe Mills at War

Based on his research and the 1923 book One Who Gave His Life, Jeffrey Hoffman depicts Mills’ war experience.

In Memoriam

Quincy Sharpe Mills is among 715 alumni in the GAA’s online Carolina Alumni Memorial in Memory of Those Lost in Military Service, a searchable database that stretches from the War of 1812 through all the American conflicts since.

At the Beginning

On the 100th anniversary of the start of World War I, the Review reported on its impact on UNC, “The Darkness Over There,” January/February 2015.

In all, Mills wrote 256 articles and opinion pieces calling for America’s involvement in the war, insisting that Americanism be forefront in the national conscience.

“Democracy, as understood and carried out in this country, to begin with, has required and does require the lives of its citizens when needed for its defense,” Mills wrote in an editorial dated July 14, 1916. “Ideal democracy is no whining beggar, supplicant to the passing benefactor; it does not exist simply by the good graces of the volunteer soldier. By the strength of its right to existence, that it may not perish from the earth, it unhesitatingly imposes the burden whenever needful.”

By January 1917, Mills’ concern for America’s future grew. “It is well enough to hope for a world in which there may be no more war,” he wrote in an editorial, “but it is well to bear in mind that, if American liberty be not preserved, the approximation of an ideal condition for mankind will not be rendered easier.”

He called for the need for men: “Guns must have pointers.”

His call for participation applied to himself. In summer 1915, he had volunteered for military training in Plattsburgh, N.Y., as part of Roosevelt’s Preparedness Movement, an effort supported by many national leaders to shore up military strength. Mills used his vacation time for the part-time training, which he repeated in 1916.

After America’s declaration of war on April 6, 1917, Mills was accepted for officer training at the Plattsburgh camp and wrote in his last Evening Sun editorial, published May 10, 1917, “That there be any other than a positive outcome of this struggle, that America should not play a heroic part in this struggle – both are unthinkable.”

The world of war

The war Mills joined was the world’s first truly global conflict, involving more than 50 nations and almost 70 million combatants. Military engagements stretched from Belgium, to the Middle East, to Africa and to the Indian and Pacific oceans. Before its end, 18 million military personnel and civilians were dead and 23 million wounded, a casualty rate of almost 26,000 a day during the 52 months of fighting.

By the time Mills arrived in France in February 1918, idealistic young Americans by the tens of thousands already had volunteered to support the Allies’ efforts. Many joined the American Field Service to drive ambulances, including notables such as Ernest Hemingway.

It was America’s entry into the war that provided the much-needed turning point leading to an Allied victory.

Letters to Mills’ parents all bore his bold signature.

Mills’ parents — mostly his mother — received almost daily correspondence from his time in Europe. These narratives often were long reflections on the war and his life in and out of combat. Many were filled with humor, some brooding about the war’s outcome, and others about family matters and missing home. With amazing alacrity his letters detail life in the trenches, the strain of bombardments and the dangers of being gassed, balanced with his observations of the intense beauty of red poppy fields and wildflowers in bloom.

On April 10, 1918, he wrote: “The trench rats are all you have heard them represented as being. I got so that I could sleep O.K. with them capering over my face and person.”

On April 14, he sent his mother photos of his life before his first taste of combat: “This inn is the one where we got the wonderful pommes de terre and chaud chocolat. We haven’t been able to get any food anywhere else in France to touch what was set before us there. We hope to return there later.”

Then on May 29, he wrote: “The bit of honeysuckle inclosed [sic] I picked in the yard of the house where Jeanne d’Arc was born. It grows in as great profusion there as around our old place at home.”

It seemed that Mills was grasping for normalcy and peace amid the chaos of war.

A farewell in advance

Upon his arrival in France, Mills wrote a letter not unlike that of many soldiers about to enter combat. In part it read:

“I would have you believe that whatever end I met, I met it with an even mind, constant in the conclusion that I would rather have gone out to this war and not come back than not to have gone at all. My chief regret, if I may not live to see the end, is that I may not witness the triumph of right over wrong in this the most terrible eruption of the forces of reaction in the history of man. That these forces can triumph is unthinkable; if they are to win, I would rather die now than witness the victory.”

It was a farewell to his mother, kept in a locker with his personal belongings.

Much of Mills’ story was captured in a 1923 book written by friend and Evening Sun editor James Luby. One Who Gave His Life contained many of Quincy’s letters and editorials along with a detailed family history. This book, along with the other items in the Southern Historical Collection, was donated by his mother in 1941.

Perhaps even more significant was his mother’s $10,000 bequest to establish the Quincy Sharpe Mills Memorial Scholarship. To date, more than 150 students have received more than $215,000 as a result of that gift. Hundreds more should benefit in the future; the endowment presently is valued at more than $300,000.

As my wife and I sat in that back room of the Wilson Library, reading his letters and holding the items he had held, we could sense Mills’ presence — and perhaps a bit of his playfulness. With ease, I photographed a number of documents for research and then found a photo of him in full uniform, a picture I wanted to duplicate. For that, my camera would not focus. At all.

Then I was a bit astounded. I learned that his closest friend in college was named Hoffman. And that the Quincy Sharpe Mills Memorial Scholarship was established in 1956, the year of my birth.

Perhaps Quincy Mills was poking me to tell his story.

Sometimes it’s simply hard to believe in coincidence.

Lt. Quincy Sharpe Mills at War

Based on his research and the 1923 book One Who Gave His Life,

Jeffrey Hoffman depicts what Mills’ war experience was like.

>>Over There

Early morning damp and mist greeted the soldiers as they dismounted from trucks that bumped along muddy, rutted roads crisscrossing what had been rich farmland. Stiff from a few days of much needed rest, the men milled about, waiting to be told what to do.

The town they left only hours before was far from the fighting. It seemed almost normal. Even with a language barrier, the locals shared food and laughter, and a few smiles were exchanged between the men and the young women who rode their bicycles close to get a look at these Americans.

Their lieutenant, Quincy Sharpe Mills, a native of Statesville, N.C., and a New York journalist of rising stature, was a little old for his rank. But his men and fellow officers loved his wit and personable ways. Gathering his platoon together, he told them to eat breakfast from their ration packs, then he conferred with other officers about expected orders and scrutinized the area nearby.

A lover of nature, Quincy Mills had spent much of his youth outdoors, hiking the thick green forests and mountainsides of North Carolina. As a college student, he and his friends were known to take long walks near campus in Chapel Hill, lost in the beauty of sun-draped trails and in their friendly debate of world events.

His present surroundings were much different. What he saw that day, near the small village of Épieds in France’s Champagne region, was more wasteland than farmland. Six years of shelling, trench warfare, and the feet of thousands of soldiers and draft animals advancing and retreating broke the land. Not much was left of the trees and farm fields. Quincy more than likely wondered what had once grown there – and what else may die there.

>>The Beginning of the End

As he looked over the area, Quincy thought about what the day may bring, weighing that reality against what had come before.

Two weeks earlier, his platoon in the 168th Regiment of the famed 42nd Rainbow Division had been part of Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing’s successful halt of a German assault near Chateau-Thierry. More than 300,000 American and French troops participated in some of the deadliest fighting of the war. Theirs was the first success of American troops led by an American general, and their efforts protected a direct path to Paris. Their fight, part of the Second Battle of the Marne, legitimately began the end of the war

But Quincy Mills knew there was much war yet to fight.

>>The Battle is Joined

Then it was time. Quincy Mills moved his platoon forward as part of the 42nd Division’s relief of the 26th Division, the New England Division, which was greatly diminished from stemming the German attack. Strangely, little fighting took place as the divisions swapped places. That day, July 26, 1918, the battlefield seemed to catch its breath as both sides gathered strength.

By mid-afternoon, the Americans were given the order to attack. There was no pretense about the price that would be paid by their lightly armed infantry moving against withering German shelling and machine gun fire. Casualties mounted, but the 42nd pushed ahead.

About 4 in the afternoon, after an hour of intense fighting, Quincy Mills, his platoon and the rest of Company G moved to a tree line next to an oat field. Raked with fire from across the field, the soldiers used what little cover they could find, mostly a few bits of trees that remained and small divots in the earth. Intensity of battle grew, and their company commander, Capt. Frank B. Younkin, was to have said, “We can do nothing but trust in God.”

>>Death and Victory

Next to the oat field, the men tried to burrow into the ground for more protection. Then came orders from battalion commanders — they were to advance across the open ground.

Concerned for his men, Quincy Mills ran ahead to seek the safest way across the field. He disappeared into the smoke of the battlefield, motivated by the brotherhood that unites all warriors. He tried to will a way to succeed.

Quincy’s men waited and about a half-hour later were heartened to see him coming back. He moved cautiously among the machine gun bullets and artillery shells that rained all around.

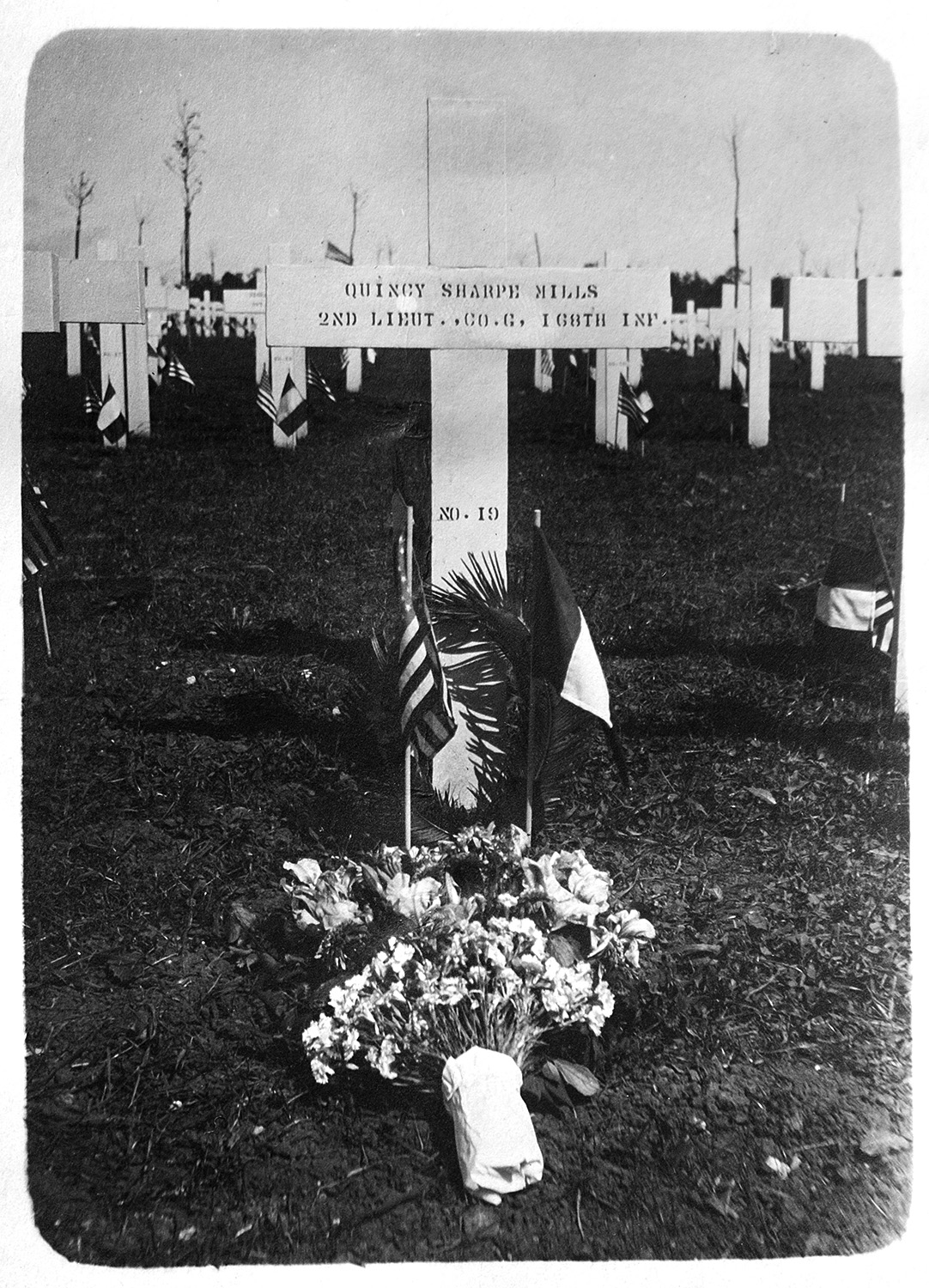

Yards from the scant protection of the tree line, a German shell exploded just feet from him as he ran for cover. Lt. Quincy Mills was hit, and along with a fellow officer nearby, was killed instantly.

Perhaps galvanized by the officers’ deaths, the American company moved across the field, eventually routing the Germans. Before advancing too far, the company’s chaplain and a few others returned to where the two officers fell and hastily buried them.

>>Epilogue

>>Epilogue

Seventy-two other members of the regiment were killed that day. Another 500 were wounded. And the War to End All Wars would cease less than four months later.

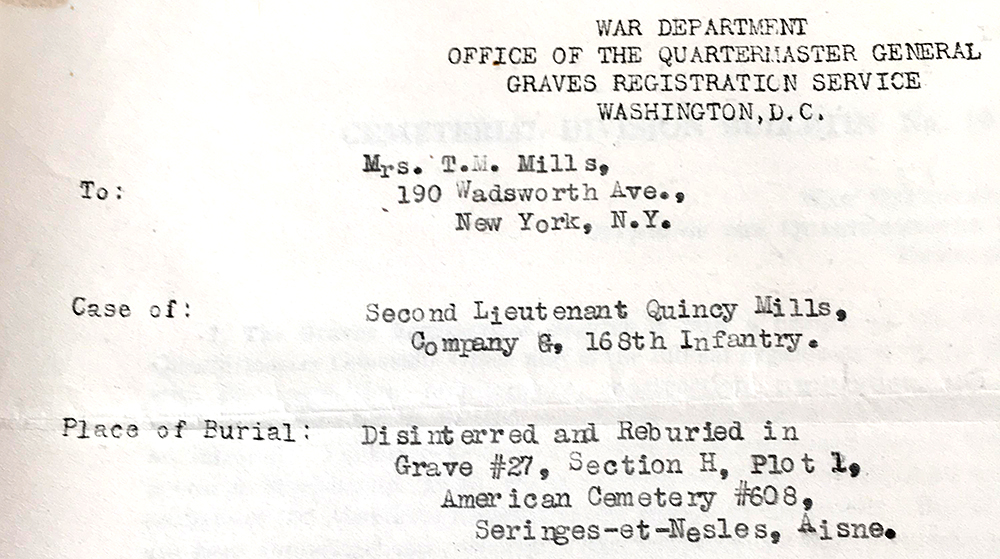

At the war’s end, Quincy Mills was reburied in the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery, about 14 miles from Chateau-Thierry, joining 6,011 other Americans who died during combat close by.

Death was not Quincy Sharpe Mills’ coda. In many ways, it led to an illumination of his life.