8 Points. 17 Seconds.

Posted on Jan. 12, 2024An improbable Tar Heel comeback 50 years ago against Duke changed how basketball is coached. It also taught us the meaning of hope.

By John Bare ’87 (’92 MA, ’95 PhD)

Some of us believe we can always come back.

— Dean Smith, in The Charlotte Observer

The game between Carolina and Duke on March 2, 1974, had it all. Hometown pride and a crosstown rival. A dustup between guards. Four seniors playing their last home game. Carolina ranked No. 4 in the nation. And most of all, an Aesop-worthy moral about the power of hope. “Isn’t this fun. You guys are going to win the game,” Coach Dean Smith told his players at the very moment surrendering fans were exiting Carmichael Auditorium.

Then the 1974 men’s basketball team rewired our thinking about what’s possible, creating a totem that coaches and fans grabbed hold of and never let go. As seasons passed and box scores faded, the legend shimmered, fueling pursuit of desires beyond the sporting life, affirming that hope removes limits and that the Buddha was right when he said, “Our life is shaped by our mind; we become what we think.”

“I went from a complete disbeliever to a rah-rah guy in the matter of 17 seconds,” said Dave Hanners ’76 (MAT ’82), a sophomore guard on the squad. “After ’74, I always thought we would win.”

During the game, with a minute left and Carolina trailing, Woody Durham ’63 — who would become the iconic radio voice of Carolina football and basketball for decades to come — offered a benediction on the Tar Heel Sports Network. “It looks like Duke may be about ready to pull off a stunning upset here,” he told listeners.

The Heels were down 8 points with 17 seconds left in the game. That’s when they spun hope out of despair. Senior forward Bobby Jones ’74 sank two free throws to make it a 6-point game. Carolina disrupted consecutive in-bound passes and scored both times. Carolina fouled. Duke missed from the line, leaving enough time for one last play: Mitch Kupchak ’76 to Walter Davis ’77 for the buzzer-beater — a bank shot sportswriter Ron Green ’78 would years later rate as “the biggest basket in the greatest comeback in ACC history.” (Timeline, page 49.)

During the timeout to set up the last shot, Smith sent in Kupchak, a sophomore, to throw the pass to Davis, a first-year. “I believed in our coach prior to that,” Kupchak said. “After that, all of us would have walked off a cliff if he told us to because we believed him so much. The game was a life lesson, to never give up. There’s always hope.”

That mysterious something

Eyewitnesses to the game in Carmichael included a future UNC athletic director (Dick Baddour ’66 (’75 MA)), a first-year high school coach (Roy Williams ’72 (’73 MAT)), a telegenic alumnus with an English degree just months away from signing with ABC Sports (Jim Lampley ’71) and a Teague dorm president making his debut keeping statistics for Coach Smith (Freddie Kiger ’74 (’77 MAT)). TV viewers included a writer and future Tony Award-winning musician and UNC English professor (Bland Simpson ’70), a future author and soon-to-be first female sports editor at The Daily Tar Heel (Susan Shackelford ’76), and a Rocky Mount teenager bound for Chapel Hill basketball glory (Phil Ford ’78).

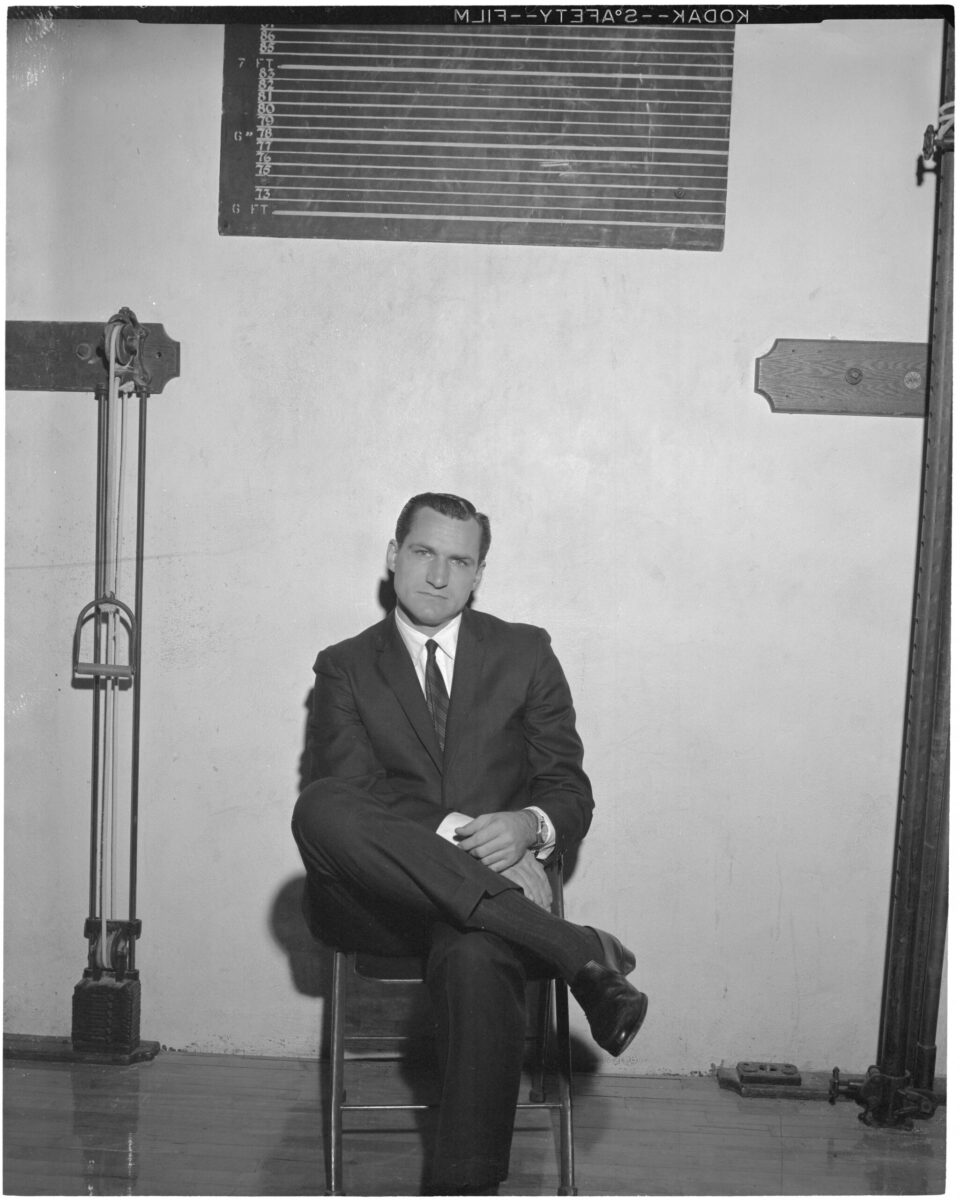

John Kuester ’77: “The stuff I remember is looking at Coach Smith’s eyes and looking at him during each timeout and hearing what he was saying and thinking, ‘Oh my, this man is amazing.’ ” (Photo: UNC Library)

Any complete video of the game is lost. No matter. Even those who saw it weren’t sure what they saw. “My memory from sitting behind the basket and being excited was that Walter hit the shot from out near the half-court line,” Lampley said. “That is not true.” Sportswriters variously marked Walter’s shot from half court, 40 feet, 35 feet and 28 feet. Today, Carolina sports information staff estimate the shot was from 25 feet.

What is certain in players’ memories is Smith’s wizardry, what one sportswriter called “that mysterious something that produces miracles.” Players’ recollections affirm the poet Maya Angelou’s observation that “people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

“The stuff I remember is looking at Coach Smith’s eyes and looking at him during each timeout and hearing what he was saying and thinking, ‘Oh my, this man is amazing,’ ” said John Kuester ’77, a first-year guard in 1974 who went on to a pro career.

Smith’s comeback magic had been evident just a couple of months before, in January, at Duke’s Cameron Indoor Stadium. With three seconds left and the game tied, Duke had the ball. Overtime appeared certain. Then Jones made a steal and scored on a walk-off layup.

Forty-two days, 39 minutes and 43 seconds later in Carmichael, Jones was fouled rebounding a Kuester miss. Duke was up 86-78. During a timeout, Smith instructed his players on what to do to win. “Guys,” Coach Smith said to the team, “I want you to understand that 17 seconds is an eternity in college basketball.”

Jones’s free throws made it 86-80. Running the defense Smith had called in the huddle, Davis then stole the in-bound pass and hit Kuester for a layup. Carolina called timeout — and Woody found hope. “It’s 86 to 82, and hold everything,” he told his radio audience.

Duke mishandled the inbounds pass and turned the ball over. With Carolina in possession, Jones rebounded a Davis miss and scored. Smith called timeout, his squad within 2 points. “It was amazing. It’s almost like he could see it happen before it happened, and he made us believe in it,” said Davis.

During the sequence, players watched the impossible turn possible. “It’s almost as if he planned to be down eight,” Kupchak said. “He wasn’t making it up on the fly. It was in his mind, and it was already planned out, and he just had to walk us through it.”

Legends benefit from what-ifs. Here’s one: At some point late in the game, Hanners would have been on the floor but for a knot in the drawstring of his warmup pants. “Coach Smith called my name,” Hanners said. “I couldn’t get the knot undone.”

When Hanners started yanking off his pants, knot and all, he stopped when he felt his basketball shorts coming off with the sweats. “That was it,” Hanners said. “Then coach called for John Kuester.”

“It didn’t take me two seconds to get my sweats off,” Kuester said.

And so it was Kuester, who’d made just eight shots all season, missing the baseline jumper with 17 seconds left that led to the foul giving Jones the free throws that started the comeback. Following the free throws and the buckets from Kuester and Jones and Duke’s miss from the line, Carolina trailed by 2. Carolina and Duke called consecutive timeouts.

“It was worry, wonder, prayer. There were three seconds left. There was enough time for people to offer supplication. Was Walter’s shot an answered prayer? Maybe,” said Mike Davis ’74, a child of Rhode Island (state motto: “Hope”) who transferred from Southern Illinois University to UNC to get a close-up look at Dean Smith’s teams and was in Carmichael covering the game for The DTH.

Then it was Kupchak to Walter for the shot to take the game into overtime. “I was about five rows up under the basket on the right edge of the aisle. I remember just being stunned,” former athletic director Baddour said.

“Un-be-lievable!” Durham, who died in 2018, yelled into his mic, defining the moment.

“It kind of elevated my dad’s legacy early on at Carolina,” said Woody’s son Wes Durham, who was 8 years old at the time and watching from high up in Carmichael’s stands. “I think it’s his greatest call.”

“Flashbulb memories”

With rational analysis pointing to a Duke win, with fans exiting, with 17 ticks left on the clock and Carolina needing four possessions to force overtime, and the possibility of a 3-point shot more than a decade away, Smith’s method and manner lifted his players.

“Coach was relaxed when we came to the sideline,” Jones said. “Coach Smith had a smile on his face. He was having fun. He conveyed that to the team. I don’t remember what he said. I remember how he said it. There was no pressure. No yelling. No cursing. We were going to execute what he told us and what he practiced.

“I think it reflects hope.”

“[It was] one of those moments in Carmichael where I thought the roof was going to collapse from the noise. I thought, I’ll never see anything like this in my life. And I haven’t.” — Freddie Kiger ’74

At home in Rocky Mount, Ford, a high school senior who would be joining the Tar Heels as a freshman in the fall, wanted to avoid watching his Carolina pals take the loss. He went outside to wash his dad’s car. When he came back in, Ford found the TV still tuned to the game and watched the Tar Heels win in overtime. Ford became a believer. “That comeback let me know that with Carolina basketball, we’re never out of it,” Ford told the Review. Twelve months later, he would lead the Heels to an ACC tournament title and become the first freshman to win tournament MVP.

Three years after the game, Harvard researchers published findings on “flashbulb memories,” moments burned into our brains due to “a high level of surprise, a high level of consequentiality, or perhaps emotional arousal.”

“You felt it in your molars, the music, the stomping, the cheering,” said Mike Davis. TV viewers experienced the electricity, too.

“You felt it in your molars, the music, the stomping, the cheering,” said Mike Davis. TV viewers experienced the electricity, too. (Photo: UNC Library)

“When Sweet D hit that shot, I came flying out of the chair and screaming and looking around for anybody to come into the room. I went around the entire house trying to find someone to hug,” said sports writer Shackelford, who was a sophomore at the time and watched the game at her home in Raleigh.

Decades later, neuroscientists would take scans of the brains of people watching basketball games and discover that when a series of plays defies expectations, pupils dilate and the brain experiences more intense activity. Our minds grab hold of these moments and never let go. “I’m 70 now. Those last 17 seconds are frozen. They’re there. One of those moments in Carmichael where I thought the roof was going to collapse from the noise,” Kiger said. “I thought, ‘I’ll never see anything like this in my life.’ And I haven’t.”

When Walter Davis’ shot dropped, nonbelievers who’d departed Carmichael heard the cheering and reentered the building. “I remember everything from that game,” said Williams, who in March 1974 was a rookie head coach at Owen High School in Black Mountain and a rookie husband. He and his wife, Wanda Williams ’72, seven months married, got tickets from Smith and sat nine rows from the floor in the east stands. “It was strange. I was sitting across from the bench,” Roy said. “The shot was made at the far end. When Walter took the shot, I was directly behind him and in line with the basket. When he shot it, I’d like to tell you it looked like it was going to go in. But when he shot it, I was holding my breath and praying. After that shot went in, I thought, ‘Oh, my gosh.’ People started coming back in.”

Watching the 1974 game, a contest with 27 lead changes, Carolina fans sloshed from cortisol sorrow to dopamine mania. “What a buzz it was. Nobody wanted to leave,” Mike Davis said.

On Friendly Lane, off East Rosemary Street in Chapel Hill, Simpson and members of Southern States Fidelity Choir, a five-piece band that was a regular at Cat’s Cradle, ran an extension cord to a black-and-white TV and watched the game in the yard. “None of us had ever seen anything like it, and we knew in the moment we had just seen a Tar Heel miracle — ‘the stuff,’ as the Bard says, ‘that dreams are made on,’ ” said Simpson, now an author and a UNC Kenan Distinguished Professor of English and creative writing. “After the game ended, we all stayed outside, whooping, hollering, toasting the moment. An older neighbor, who kept a large garden, came busting out of his house all charged up too and started pulling weeds, joyously throwing them up in the air and shouting right along with us.”

Linnea Smith ’76 (MD), Dean Smith’s widow and a psychiatrist who focused her research and advocacy on childhood trauma and maltreatment, rarely commented publicly on Carolina basketball. For her, this game was different. “There are people studying positive emotions, happiness and joy — and this is another category above that, which is more profound and encompassing: awe,” Smith said in an interview. The 1974 game is one of her favorites, she said, and it sticks with us because “it was unexpected, beyond the normal range. The wonderment, the awe, make this a particularly strong memory for those who saw it.”

What it was, was hope

Buoyed by awe, fans experienced “moral elevation,” which primes us for hope. “Hope is not wishful thinking,” said Chan Hellman, director of University of Oklahoma’s Hope Research Center.

It’s something more. Hope is our ability to grasp what’s required to reach our goals plus the wherewithal to take the actions needed to get there. In her 2023 book, The Power of Hope: How the Science of Well-Being Can Save Us From Despair, Carol Graham, an economist at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C., quantifies the effects of hope. Her research shows that with hope we work harder, work smarter and achieve better outcomes.

Others, having nothing to do with sports, saw that, too, and saw it as a teaching tool. In the late 1980s, a Navy commander based in Norfolk asked Baddour for video of the last 17 seconds. The officer, Baddour said, showed it to inspire civilian managers working under immense pressure to finish repairs on the USS America aircraft carrier. CEOs made similar requests. “They wanted to use it in their work to demonstrate that when all seems lost, there’s hope, that here’s what teams can do,” Baddour said.

What we may all take from the game is that we can become so captivated by our desire to accomplish something that we no longer imagine any alternative result. It comes down to focus. When prospects of failure occupy our minds, hope dims. When we achieve a state in which nothing intrudes on a commitment to make something happen, hope grows.

Coaches used the game to instill hope in players when a win seemed impossibly out of reach. “Every coach knows about it, about how Coach Smith was so great with time and score,” Roy Williams said. “From a coaching viewpoint, it meant something to thousands of people who happen to be in the coaching profession.”

Tony Barone, an assistant coach for Duke in 1974, was head coach at Creighton 15 years later when he told a sports writer, “I don’t think anything has ever come close to it. I’ve got a copy of the film, and I’ve shown it to the team every year I’ve been at Creighton. You can tell a kid it’s never over ’til it’s over, but those are just words. When you show them proof, it’s a lot different.

“Funny thing is, they don’t believe it even when they see it.”

Even Duke players took lessons from the game into their future careers. Kevin Billerman was a Duke guard who set a school record with 14 assists during the game and tangled with Carolina senior guard Ray Hite ’74 in the first 2 minutes of the contest. He was confident Duke would win until teammate Pete Kramer missed a free throw with 3 seconds to play, giving Carolina a chance for a game-tying shot.

“That’s something you dread after being up eight,” Billerman said. “Opportunity to beat a top-five team at their place on TV. That was a tough row to hoe.” Recalling the last play in regulation, Billerman said Duke head coach Neil McGeachy, thanks to diligent scouting, correctly predicted Carolina’s in-bound play and drew up the right defense in the team huddle. “We messed up the play,” Billerman said.

Billerman carried lessons from the comeback into his half-century of coaching. “The things you can learn from Dean Smith and his program are immense,” said Billerman, who’s now the head coach at Ravenscroft School in Raleigh. “The way he fouled and kept telling his team they were in the game: ‘We’re going to win this game.’ You heard all about it. That becomes part of your coaching philosophy: We’re still in this. Let’s go do this.”

Parents even found inspiration for childrearing. While a student in the 1980s, Diane Sutton ’87 could frequently hear the roar of the crowd in Carmichael from her Connor dorm window. Even though she graduated more than a decade after the comeback, she was aware of the game and later used it as a parenting tool. “I’ve shared the play-by-play of the last 17 seconds with my kids multiple times,” said Sutton, founder of VisionPoint Marketing in Raleigh. “Before they saw the ’74 game clips, they didn’t believe that a team could overcome an 8-point deficit in 17 seconds. After that, the adage of ‘never give up’ was more than a supportive message. It became a rally cry.”

What they may all take from the game is that we can become so captivated by our desire to accomplish something that we no longer imagine any alternative result. It comes down to focus. When prospects of failure occupy our minds, hope dims. When we achieve a state in which nothing intrudes on a commitment to make something happen, hope grows.

Any complete video of the game is lost. No matter. Even those who saw it weren’t sure what they saw.

“The more improbable we take an outcome to be, the less likely we are to hope for it — the improbability easily swamps the possibility,” Andrew Chignell, a professor of religion and philosophy at Princeton University, wrote in the January 2023 issue of The Philosophical Quarterly. “But other things are not always equal: Sometimes we hope against hope for things that we take to be extremely unlikely — just barely possible — by fixing our focus in a way that sidelines the long odds. Often this happens when and because the desire is very strong.”

The Hope Research Center’s Hellman said legends, such as the 1974 game, are models of hope that stir us to believe we can succeed, even in unfavorable conditions. “Think about the essence of these legends, overcoming obstacles when all seems lost,” he said. “One thing I really like to consider in these folklore is the idea that hope is a social gift. That is, legends only become legends because of the group’s presence. Hope doesn’t happen in isolation; it happens in relationships.”

Through social connections, we discover “collective hope,” which Hellman said is “the shared belief we can set goals and cast a vision of the future, that together we can find the pathways and navigate barriers, and there is a shared energy toward the pursuit of this vision. Having an identity toward a team is an emotional bond. When the team wins, I win; when the team loses, I lose. Therefore, the telling and retelling of the story enhances the commitment toward the legend and gives a sense of belonging — the social gift.”

“Identity fusion”

The hope born out of the 1974 comeback wasn’t just inspirational talk, or as Hellman put it, “wishful thinking.” For it to mean something, for it to carry the power of a legend and not the whimsy of a fluke, it had to produce ripple effects. It had to reveal itself again, at another moment when all seemed lost. It had to give coaches and players the belief they could control their fortunes. Just one year later, the hope from 1974 rippled.

In the opening round of the 1975 ACC tournament, Carolina was down 8 points to Wake Forest University, with less than a minute to play. Sports writers were chirping about a Carolina loss and queuing up at the Wake Forest locker room for interviews. Then, out of the blue, “UNC did it again,” Jack McCauley wrote in Winston-Salem’s The Sentinel, revisiting the tale of 8 points, 17 seconds and wondering what it felt like for Wake Forest assistant coach McGeachy, who’d been the Duke head coach in 1974.

Jim Braddock ’83, a member of UNC’s 1982 national championship team, said the 1974 game is “one of the most spectacular comebacks I’ve ever seen.” He said Smith used the game as a teaching tool. “When I got to North Carolina, we watched that film,” he said. “Those comebacks were not coincidence. We would watch those come-from-behind games on film and go out and spend time on those situations at the end of practice.”

Such methods built belief. Smith curated demanding, precise practices that sewed inside players a protective lining of poise. “It’s the mental part of it,” Williams said. “If you’ve done something several times, you’re prepared. You believe.”

Wes Durham said his father, Woody, believed UNC should have marked the spot on the Carmichael court where Walter Davis made the game-tying shot. Not because it was a buzzer-beater shot from long range, Wes said, “but for what got the team to the shot. All the things that Coach Smith talked about as a team were exemplified in that process.”

To survive, of course, a legend needs fans to continue retelling the story. And in turn, the retelling does something for us, Shackelford pointed out. “We sit around the dinner table and share these stories because sports represents our core cultural values, and one of those is that we fight to the very end,” she said. “We share stories that feature teamwork. We share stories that represent hope.”

It turns out the 1974 game did teach us about hope — and fastened us together. Sharing brain-jangling experiences does that. Researchers call it “identify fusion.” It’s the reason the battle of Waterloo, as the saying goes, was won on the playing fields of Eton. And it’s how Walter Davis, Braddock and Sutton’s kids all end up members of the same tribe. What’s more, the gatherings touch our hearts. During these “collective events at which emotions run high,” according to research published in the journal Nature in 2022, our heartbeats synch. Yep, fans in Carmichael found their hearts beating as one on March 2, 1974. It’s what happens when people fall in love.

In those 17 seconds, we found hope. We fell in love. We didn’t want to leave. We wanted to hold on forever. The legend remains fixed in the minds of those who saw the comeback and those who produced it, their philosophical reflections — the bearing of Coach Smith — having melded to the visceral experiences — the verve of the pep band – to form an inviolable Tar Heel alloy.

But one detail stands out for most Carolina fans, a flashbulb-popping detail still easily retrievable from the amygdala’s memory bank. Reflecting on the game and its deeper meaning, UNC statistician Kiger, sitting in a Franklin Street eatery, slides his chair back from the table, throws his arms up and says, “Just flat out, we didn’t want to lose to Duke.”

John Bare, a writer and photographer based in Concord, is the author of My Biscuit Baby, a novel set in Chapel Hill.

TIMELINE

“Ba, ba-ba-ba-ba … ba-ba-ba-ba,” senior forward Bobby Jones ’74 sang into the telephone, the melody of a Carolina fight song clear in his mind on the 50th anniversary of the feat Sports Illustrated called the “gold standard for miracle comebacks.”

“During one of those timeouts in regulation with 17 seconds left, the UNC pep band played the North Carolina song,” Jones said. “Being from Charlotte, it always made me really proud to hear that song. I always felt proud to represent North Carolina. When I heard it during the timeout, it made me think, let’s do this for North Carolina.”

Here’s how they did it, second by second.

1:00 (UNC 78, Duke 84)

Duke rebounds a UNC miss and brings the ball up the court leading 84–78. Duke calls a timeout. Radio announcer Woody Durham: “It looks like Duke may be about ready to pull off a stunning upset here of the nation’s fourth-ranked basketball team.”

0:51 (UNC 78, Duke 84)

Duke in-bounds the ball. Carolina fouls Duke guard Tate Armstrong.

0:45 (UNC 78, Duke 84)

Armstrong misses the free throw. UNC rebounds; senior Darrell Elston misses a jump shot. Duke rebounds, makes outlet pass to Armstrong, who’s fouled by Elston on layup attempt.

0:23 (UNC 78, Duke 86)

Armstrong hits two free throws. Duke players on the bench “standing up cheering like crazy,” Tar Heel junior Ed Stahl told The Charlotte Observer. Duke 86, Carolina 78.

0:17 (UNC 82, Duke 86)

Duke fouls senior Bobby Jones. He makes two free throws. Duke 86, Carolina 80. Duke makes a poor inbounds pass. Walter Davis grabs the loose ball, feeds first-year guard John Kuester for a layup. Duke 86, Carolina 82.

0:13 (UNC 84, Duke 86)

Duke mishandles the inbound pass under Carolina’s basket and turns the ball over. Carolina inbounds. Kuester misses a shot but Jones rebounds and scores. Duke 86, Carolina 84.

0:06 (UNC 84, Duke 86)

Duke inbounds pass. Kuester immediately fouls Duke’s Pete Kramer, a 58 percent free-throw shooter.

0:04 (UNC 84, Duke 86)

Kramer misses the front-end of the one and one. Junior Ed Stahl grabs the rebound and Carolina calls time out. Duke 86, Carolina 84.

0:03 (UNC 84, Duke 86)

Duke Coach Neil McGeachy calls a timeout and correctly predicts what play Carolina would run, according to Duke guard Kevin Billerman. Other accounts said he told his players Carolina would try to pass the ball to the 6-foot, 9-inch All-American Jones under the basket. Dean Smith sets up a play for first-year Walter Davis to receive the inbounds pass.

Kupchak passes the ball to Davis at half court. He takes three dribbles, pulls up 25 feet from the basket with a Duke defender lunging at him and banks in the shot as the buzzer sounds. Duke 86, Carolina 86.

0:00 (UNC 86, Duke 86)

Carolina wins in overtime. Final score: Carolina 96, Duke 92.