A Long Reflection

Posted on July 30, 2021His assignment on the healing end of history’s largest naval invasion became an extraordinary performance. Jack Hughes ’39 paid back his survival to his profession and his community.

by George Spencer

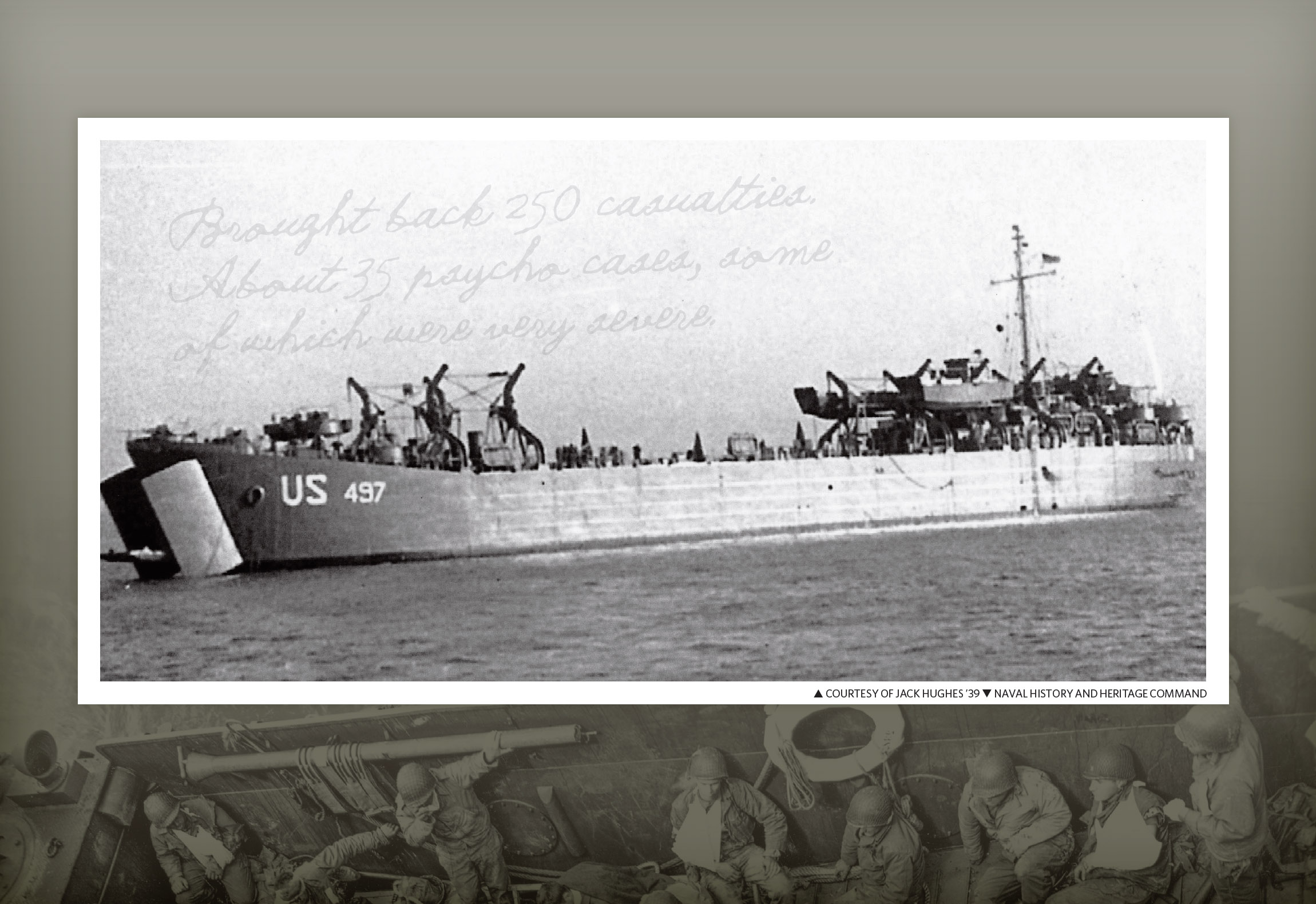

Dawn on D-Day found Lt. j.g. Jack Hughes ’39 perched on the bow of LST 497, a flat-nosed, flat-bottomed 328-foot tank landing ship, as it hammered and banged and humped its way to Omaha Beach, one of some 6,000 warships in Operation Overlord, the largest naval invasion in history.

Salt spray in his hair and buffeted by a stiff, chill wind, Hughes, 24, was a newly minted doctor. As the black of night became gray, he could just make out the cliffs ahead. Like 40 of his male relatives, he was doing his part.

“It wasn’t bravery,” Hughes insists. “It was a matter of ‘had to’ or learn German or Japanese and be in a slave labor camp. We did what we had to do.”

Hughes had come a long way from tiny Tabor City, flat against the South Carolina border. His father’s company made crates for locally grown strawberries. An industrious teen, Jack sold ice at the beach. He hawked Johnson tomatoes from his garden for a dime apiece. After high school, which he completed at age 15, he raised strawberries, but a year behind a plow gazing at the hindquarters of an old mule led him to tell his father, “You know, I don’t believe I want to be a farmer.”

Hughes is 101. He and his wife, Scott, 99, have been married for 21 years. Both are healthy in mind and body.(Grant Halverson ’93)

There wasn’t much excitement in town, especially on Sunday afternoons. “There were no movies. You didn’t have parties. You didn’t dance. The radio reception was terrible. You didn’t have anything to do but go to the drugstore for an ice cream cone, and that took 30 minutes.”

At Chapel Hill, he did the usual things. He went to dances in the Tin Can. He played poker and craps. When President Franklin Roosevelt came to campus in 1938 in his Cadillac convertible, Hughes stood in front of South Building as he rolled by. “I could have touched the car,” he remembers. “I don’t remember seeing him talk. My father was a Republican, so I might not have.”

He struggled with a chemistry test and considered dropping that as a major — until he remembered his time in the strawberry patch. “I swear I could feel those plow lines running around the back of my neck. I said, ‘Damn it, I ain’t going back to the farm.’ ” He would get his medical degree from Carolina, too, in 1941.

“ ‘Not to worry,’ we’d be fine”

An ocean away from that farm, his khakis pressed against the cold steel of the bow, Hughes found himself under orders from Roosevelt, now his commander-in-chief. Actually, he was disobeying orders. He decided his decidedly unheroic battle station — a windowless paint locker in the stern — was no place to be. Not this morning. At the tip of the spear of the campaign to free Europe from the Nazis’ iron heel, Hughes would take in everything the armada had to offer.

He was not that worried. There wasn’t going to be that much shooting. At a briefing, he had been told that “it would be duck soup for us and the Navy.” Here is how it would go down: At daybreak, 0550 hours, the battleships USS Texas and USS Arkansas and other warships would fire barrages at the 35 four-foot-thick concrete pillboxes on Omaha’s bluffs. Above the blanketing clouds, 1,350 U.S. heavy bombers — B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators — would bomb them to ashes.

Hughes is 101. He and his wife, Scott, 99, have been married for 21 years. Both are healthy in mind and body. He retired in 1988 after 38 years in private practice as a urologist.

His LST (to the sailors, Large, Slow Target) would plow onto Sector Fox Red on the five-mile-long Omaha Beach at 0800, 90 minutes after the first wave of troops. Its bow doors would swing open. A short ramp would slide out. Its cargo of 20 Army doctors, their portable field hospital and dozens of 155 mm howitzers would offload. A few wounded would come aboard, and off they’d go. Once troops got further inland, sure, they’d have trouble, the briefer said, adding, “ ‘Not to worry,’ we’d be fine.”

But at Omaha, none of the pre-invasion bombs hit their targets. None of the shells did any damage. Amphibious tanks sank. Landing craft wallowed. Soldiers drowned. Those jumping into chest-deep surf got chopped into body parts by well-planned crossfire. The water ran red.

“I couldn’t believe what I was seeing,” Hughes said. “I felt a little like Julius Caesar in that I came and I saw, but what I saw wasn’t supposed to be happening.”

With 0800 moments away, the ever-nearing beach loomed perhaps a half mile ahead. Hughes saw vehicles burning. Mayhem. Yet onward his ship banged and bumped, second in line behind an LST 200 yards ahead. A U.S. destroyer raced straight toward shore, black smoke pouring from its stack. Veering sharply at the last instant, it let loose a broadside volley at the cliffs. “It fired point blank at one of the pill boxes, and the shell bounced off. It knocked off a little chunk.”

Then … what? — the beach blazing, guns’ thunder — the first LST … what? Confusion. Something. There’s smoke coming from its bow. “I don’t know how much I saw,” Hughes recalled. “It scared the hell out of me. I knew it had gotten hit. I turned tail back to my general quarters station where I was supposed to be.”

Always a leader

Hughes is 101. He and his wife, Scott, 99, have been married for 21 years and live in a retirement community in Durham. Both had COVID-19 last fall. Both are healthy in mind and body, though they use rolling walkers to get around. He retired in 1988 after 38 years as a urologist.

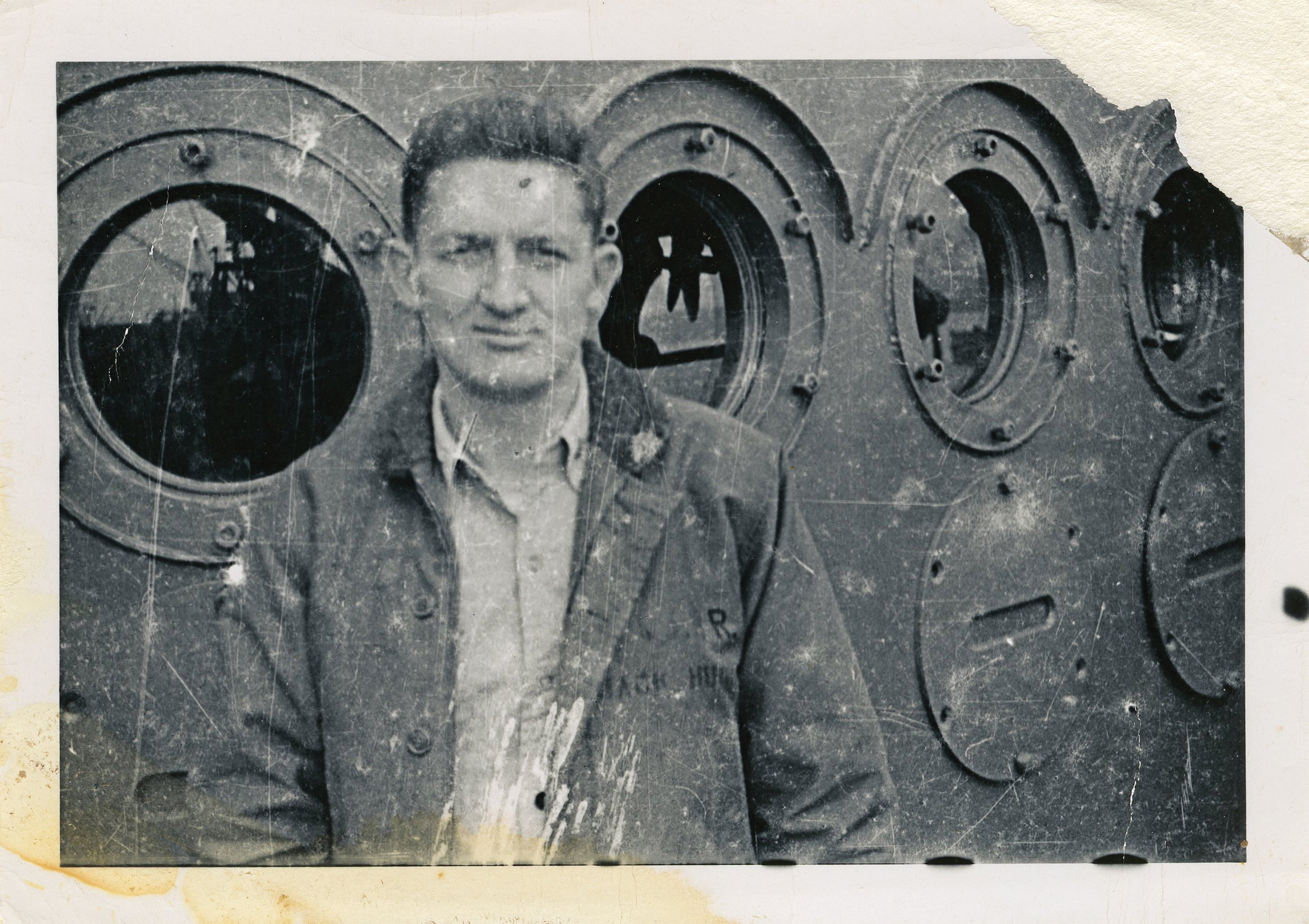

A lifetime of diagnosing patients gives his gray eyes sharp intent, yet the grin that plays on his face makes him seem a bit of a rascal, a scamp — as if he knows something you do not. With his hearty pink complexion, he could pass for a lad of 80. A photo of him on the LST shows a dashing young man. Confident in his sea coat, shirt collar unbuttoned, square jaw set, he gazes with steely intent at the camera.

He is and has always been a leader. After he was inducted, a friend volunteered him without his knowledge to be the executive officer over dozens of other doctors and corpsmen. While crossing the Atlantic in April 1944 and at other times, he preached the gospel. “Held church for the Boys,” he wrote. “Rather enjoyed it. Read the 100th Psalm & talked 10 mins on thankfulness. … Guess I’ll have to start living better if I’m going to lead Church Services.”

He led a more than active professional life. “It’s part of my nature,” he told a newspaper reporter in 1984 when he was elected president of the N.C. Medical Society. At various times he was president of the Carolina Urological Association and the state chapter of the American College of Surgeons, head of staff at Durham County General Hospital, secretary of the state medical society, vice president of the Durham Chamber of Commerce, and he chaired Operation Breakthrough, a Durham anti-poverty program. He found the time to raise six children. He has nine grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Patching up Omaha

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill wrote in his diary: ‘‘The destinies of two great empires [are] seemingly tied up in some … damned things called LSTs.’’ Hughes didn’t know it, but the 230 LSTs at Normandy were the fleet’s most valuable ships. A shortage of them had threatened to delay the invasion. They were so valuable that British Adm. Sir Bertram Home Ramsay, the man in charge of Operation Neptune, Overlord’s naval operations, had forbidden them to land at Omaha on D-Day. Instead, at a safe distance, they would off-load supplies to small ferry-type vessels.

So, there being too much action close to shore, Hughes’ LST fell back and spent the rest of D-Day five miles out maneuvering between the cruisers USS Tuscaloosa and USS Augusta, the flagship of Ramsay and ground commander Gen. Omar Bradley, who was so worried about Omaha he considered withdrawing forces there and re-landing them on Utah Beach, a notion Ramsay overruled.

“People tend to be obsessed with D-Day, and I understand why — it’s a moment in time, but what makes the invasion work is not what happens on June 6,” said Craig Symonds, professor emeritus and former chair of the history department at the U.S. Naval Academy and author of the book Operation Neptune. “It’s what happens through June and into July, getting the million men across the channel and their equipment, fuel, food and supplies, so they can expand that toehold. That’s what LSTs did. That’s what made D-Day a success.”

During his six months on LST 497, Hughes made 28 round trips involving many destinations with only a few days off.

At midnight on the morning of June 7, Hughes went to work. In heavy seas, his LST met a landing craft packed with 100 wounded, all of whom were well sedated. He ordered corpsmen to go down and put them in wire baskets called Stokes stretchers to lift them aboard. When that team got seasick and came back up, Hughes went down in the dark with another corpsman. As 10-foot waves surged, they hoisted up the remaining men. “We were throwing up everything but our toenails.”

“He’s being banged around with no light and having to rig a hoist. You’re talking about a major procedure to get the wounded up without getting further injured,” said Jan Herman, the Navy’s retired chief medical historian and author of Battle Station Sick Bay: Navy Medicine in World War II.

An 8-by-12-foot operating theater waited in the stern. “We had amputations, chest wounds and all that sort of thing,” Hughes said.

When Hughes reflects on D-Day, he wonders what might have happened if his LST had been elsewhere or gone further in. Luck, he believes, made the difference. “I get a feeling,” he says, “a lot of us would have ended up like thousands of others on the beaches.”

Hughes played a much bigger role than was originally envisioned, according to Joe Balkoski, author of Omaha Beach and six other books on D-Day and the 29th Division that landed there. “He had to deal with critically wounded people who had not been stabilized on shore.” Because of the chaos, the Army could not set up field hospitals. “The unexpected impact on him was very significant. You had to get the wounded, particularly those who might die without plasma, onto ships under the care of Navy doctors and to England as soon as possible.”

Hughes and his LST went ashore on June 8. All was calm when he climbed the bluffs to see destroyed pillboxes. He can’t remember whether he walked a marked path to avoid minefields or if he heard random German shells hit the beach. “Those three days accounted for about all of my active participation in WWII,” he said. “The rest of my time was mostly as an observer.”

Being humble is “a very, very common thing” for men like Hughes, according to Balkoski, who over the past 40 years met 800 members of the 29th at reunions. “Very few I ever talked to ever said they ever did anything exceptional. I felt like they mostly didn’t want to talk about themselves because more people were more unlucky than they were.”

Luck, Hughes believes, made the difference. When he reflects on D-Day, he wonders what might have happened if his LST had been elsewhere or gone further in. “I get a feeling,” he says, “a lot of us would have ended up like thousands of others on the beaches.” Nearly 3,000 men were killed or wounded on Omaha that day, losses worse than the other four beaches combined. Between June 12 and June 16, thanks largely to LSTs, the Allies landed 75,383 men, 10,926 vehicles and 66,571 tons of supplies on that beach alone.

Hughes attributes his long life to luck, good genes and common sense. “Eat moderately. Exercise moderately. If you drink, drink moderately. You can’t smoke moderately. Just good clean living,” he said.

Freelance writer George Spencer lives in Hillsborough.

The Lieutenant’s Diary: “May There Never Be Another”

Jack Hughes kept a diary.

“I’m sure somewhere along the line somebody told me not to, but it never registered on me,” he says with a smile. This 6-by-7-inch notepad, its pages darkening with age, contains dozens of entries in ink. His neat cursive script details the panorama of military life from stretches of boredom to moments of terror.

On March 30, 1944, his convoy gets ready to leave for Nova Scotia. “We go tomorrow. Oh Lord!” Three days later, he muses, “Wonder when (& if) I’ll get seasick.” This is the least of his worries. He confides, “My life raft is so far forward from my battle station in the ward room I’ll never make it if it ever becomes necessary.”

In the mid-Atlantic, he thinks about “Patrick Henry’s words” and adds: “Guess what we’re fighting for is to be able to do things & live the way we want to or die fighting for it. At least that is what I think I’m fighting for. Anyway we shall see.”

In the mid-Atlantic, he thinks about “Patrick Henry’s words” and adds: “Guess what we’re fighting for is to be able to do things & live the way we want to or die fighting for it. At least that is what I think I’m fighting for. Anyway we shall see.”

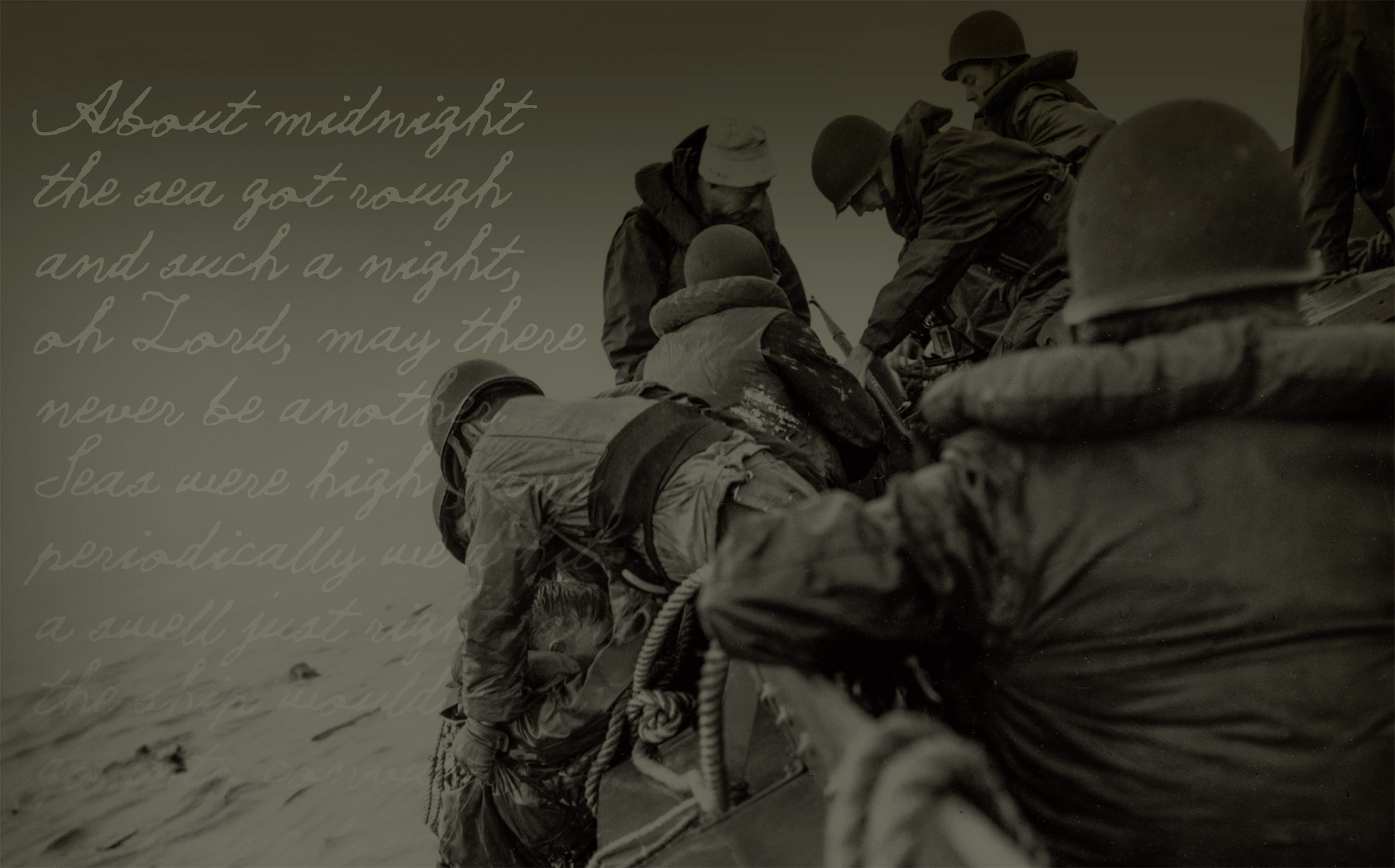

His seasickness fears soon come true. “About midnight the sea got rough — and such a night, oh Lord, may there never be another. All the things I’ve heard about LSTs I now know are true. Seas were high — 30 feet, and periodically we’d hit a swell just right, and the ship would seem to go into convulsions, snapping loudly with each jerk and then vibrate like a tuning fork. The engine gave out an unsteady agonized groan constantly through the night.”

The solemnity of looming battle sinks in on May 8: “[My friend] Manning is definitely dead. His ship took a fish. … The going is really going to be tough. Don’t feel like writing.”

After reading the diary, few would call Hughes a mere “observer.” Ten days after D-Day, as he neared Dover, German guns 20 miles away lobbed radar-guided shells at his convoy. One landed 200 yards away; shrapnel hit his ship. On June 21: “Two bombs [landed] about 50 yds off starboard side last night — scared my pants off.”

Later entries read “[LST] 496 sunk. … Others are hitting mines. Wonder if there’s one with our name on it — if so let it come.”

The LST hauled aviation gas and ammo on one trip. “Glad to get it off — one hit and we’d all be French fries.” On two occasions he sees five “buzz bombs,” German V-1 rockets flying to England. He spots another in searchlights over Omaha — “It had boomeranged back” toward the Germans.

Ferrying wounded continues. “Brought back 250 casualties,” he writes. “About 35 psycho cases, some of which were very severe.”

“Life is getting monotonous — just eating, sleeping & reading,” he wrote a month after D-Day, but on July 29, German planes dropped three bombs on a ship 1,000 yards away. “Didn’t know whether to crap or go blind,” he writes. “Next thing I was picking myself off the deck as people walked over me. … Thought about the possibility of getting it. For some reason it didn’t worry me much. Guess it’s because we calloused our minds with a pseudo-fatalistic attitude of ‘I’ll get it when my time comes & not before, but it’s better not to tempt fate.’ ”

A moment for medical history came in August when a machinist’s mate developed symptoms of appendicitis. The LST was crossing the channel, a daylong voyage, and the Army doctors had taken vital surgical supplies. “We had to have some instruments, particularly skin retractors, so I went to the galley, got forks, took them to the machine shop, and made skin retractors. I needed deep retractors, too, so I got spatulas, bent them right, and put them all in the autoclave.”

The captain got permission to leave the convoy and landed at Utah Beach so Hughes and another doctor would have a stable platform to operate. When he paused to look up during the procedure, he saw three or four sailors watching from a hole in the canvas roof. It was “a hot appendix,” Hughes wrote, and “tough to remove” because it was “bound to the cecum [the large intestine].”

Navy medical historian Jan Herman knows of no other major operations on an LST during the campaign, especially using “rudimentary” instruments. “In the early 1940s, even if you went to a good hospital with appendicitis, there was no guarantee you were going to survive, because antibiotics weren’t widely available,” he said.

The surgery stands as a metaphor for the larger story of D-Day, according to historian Craig Symonds. “A lot of things that made it work were unanticipated decisions made on the fly like this. ‘Here’s an unexpected problem. Well, let’s figure out a way.’ It says a lot about the Allies — and particularly the Americans — that they had the attitude that we’ll figure this out. That’s what Hughes did.”

Hughes returned to New York on Dec. 26, 1944, and reported to Parris Island Marine Base in South Carolina, where, he says, “I spent the next 20 months fighting a war against malaria and venereal diseases” among troops returning from Guadalcanal.

— George Spencer

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.