A Nation’s Promise

Posted on April 29, 2020

(Illustration by Jason Smith ’94)

The war was over 75 years ago. Josh Fennell ’01 digs diligently through archives and European cornfields on an earnest mission — that no one is left behind.

By Dan Carlinsky

The case is on the books as MACR 7651. A Douglas C-47 troop transport plane left an airfield in eastern England, flew over the channel, dropped its load of 14 paratroopers into the darkness shortly before 3 a.m. on D-Day, was hit by enemy fire and never returned. All five crew members perished. Two were found by fellow GIs; the other three were not.

“A C-47 is basically a fuselage with fuel tanks,” Josh Fennell ’01 explains. “When it goes down, it hits the ground and just crumples and burns.”

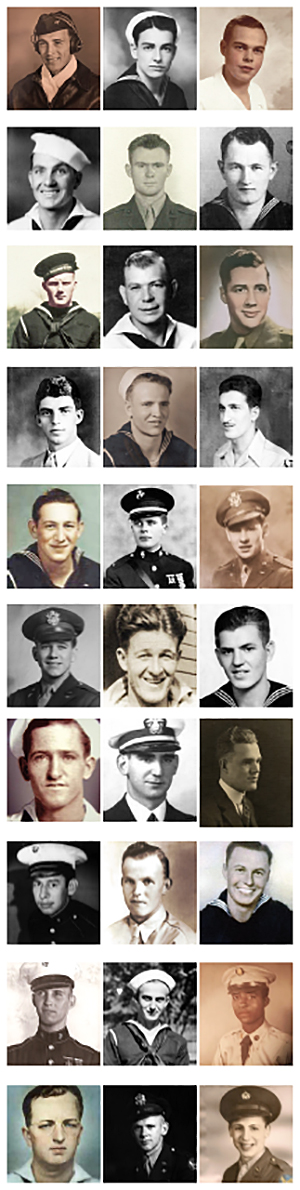

Fennell’s fascination began with archival research. “I had no idea how appealing the work would turn out to be.” The servicemen shown on these pages, all formerly unaccounted for, have been identified by the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency. (Photo courtesy Josh Fennell)

Fennell and his team — two other historians, a military research analyst, an archaeologist and two translators — have come to a just-harvested cornfield a few miles north of Sainte-Mère-Église on this autumn day. They believe they’ll find the crash site to perform a field investigation, hoping their efforts will uncover remnants of the plane. With skill, experience, hard work and a little luck, they also hope to make an important recovery and, perhaps, identification.

The five brothers who own the farmland already have approved the search (the French Ministry of Culture, too) and prepared the way for the Americans by plowing under the remaining cornstalks. Fennell and his team are armed with a compass, a 100-meter measuring tape, three heavy-duty metal detectors, pinpointer metal detection wands, trowels, shovels, small colorful surveyor’s pin flags, a mesh screen with 1-centimeter square openings, a handheld GPS, a laser rangefinder and a digital camera. They lay out a grid pattern on the field and begin to examine the ground with meticulous attention.

Fennell records the proceedings by hand in a notebook with waterproof pages. It’s a sensible precaution. “In this part of France,” he says, “you can pretty much expect some rain at any time.”

One of the landowners stops by in his tractor to check the group’s progress. A local amateur World War II researcher who has been instrumental in helping narrow the search location visits to discuss other sites he’s been looking into. A policeman pauses to watch for a few minutes. A reporter for a regional newspaper pulls up, sniffing a story. The reporter is right: It’s a story.

Asked why Americans are still looking for their war dead 75 years later, Fennell has a ready reply: “Because in the United States we never abandon a missing soldier.”

Asked why Americans are still looking for their war dead 75 years later, Fennell has a ready reply: “Because in the United States we never abandon a missing soldier.” A historian with the U.S. Government’s Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, or DPAA, he is leading the team to five locations over three weeks in northern France, tracking service members still officially missing in action.

The group will spend nearly five days here in search of MACR 7651.

In Sainte-Mère-Église, the market town of a rural corner of Normandy half a dozen miles from the channel, you can’t travel far without encountering a reminder of the events of June 6, 1944. That’s understandable: The town and the surrounding area — a blend of quiet hamlets, lush pastures, apple orchards and cornfields — were a key center of the historic air and sea assault that launched the Allied drive to end Nazi occupation in World War II, still known in France simply as le Débarquement — the Landing.

The liberators who arrived by parachute overnight to join their comrades hitting the shore at dawn are remembered today in the American flags that flutter in front of the town hall and at checkout lanes in the local Super-U. Streets are named for “Général D.D. Eisenhower” and other notables of the U.S. military. In the church, a giant stained glass window depicts paratroopers dropping from American warplanes past Mary and the infant Jesus to the town square below. There seems to be a dedication plaque on every third building.

Even three and four generations on, the young in this region are raised on stories about the waves of Yankee soldiers — 16 million of them, eventually — who came to save France and all of occupied Europe, especially the 400,000 who didn’t get back home. “In Normandy,” says the town’s mayor, “we remember.”

Even if you can’t find family

Fennell grew up in Charlotte and, as he tells it, attended UNC because he idolized Dean Smith and his teams. “Carolina was the only college I applied to,” he said. He entered as a pre-med biology major but switched — he was interested in science but admits he wasn’t very good at it. When he started taking history courses, it “blew my mind” how interesting that could be. He earned a master’s at the University of Illinois at Chicago and entered the doctoral program, planning to research industrialization in the South. He needed a job while working on his doctorate and saw a posting in the National Archives in Washington about a paid fellowship to research missing soldiers from World War II.

“Both my grandfathers were in World War II, but I didn’t know a whole lot about the war. I did know that a lot of the papers I wanted for my own research were at the Library of Congress, so Washington was a good location for me — certainly better than Illinois. I had no idea how appealing the work would turn out to be.”

Besides archives research, Fennell conducted informational meetings across the country with next of kin. He found the experience more than educational:

“I saw widows. I saw children who had never met their fathers. It was heartbreaking. Once I started, it became a mission. The way I see it, the military can reach into a family and pluck out a member and not return them, so I think it’s someone’s obligation to at least tell that family — whatever generation — the story of what happened. There’s also a second obligation, even if we can’t find any family, and that’s to the service member himself. There’s a promise that must be kept.”

He signed on with a Department of Defense group that was a forerunner of the current agency. Today, the DPAA, whose motto is “Fulfilling Our Nation’s Promise,” is headquartered in Virginia near the Pentagon, with a large forensic identification lab at Pearl Harbor and satellite operations at Air Force bases in Ohio and Nebraska. Its charge covers missing personnel from conflicts back to World War II, employing historians, analysts, explosive ordnance disposal technicians, forensic anthropologists and archaeologists, forensic photographers, linguists, mountaineers, divers, genealogists and other specialists.

For the agency’s historians, the basic activity is a continuous search for information, always looking for new sources. “One of our core tasks,” Fennell said, “is constantly churning through the files — war records, National Archives, foreign archives.” But to start, he takes to the internet.

Allied and German paraphernalia found in the search for remains of missing service people. (Photo courtesy Josh Fennell)

“The cardinal rule is, ‘First, Google your case.’ Our job is to read as much as possible on each case file — even things that are only tangentially related, so that when two kids playing in the woods find something you recognize it as a clue that might be helpful.”

He also exchanges information with families looking to learn about a deceased relative — “They sometimes know things we don’t” — and with hobbyist researchers, like a dairy truck driver in Normandy who spends his spare time searching for and writing about C-47 crash sites.

Amateurs have provided some of his best leads. And he was surprised to learn when he started how seriously some part-timers pursue their passion.

“Folks who live in the area are really the experts. Some of them are following up on stories their parents and grandparents told them about what happened during the war. And maybe it’s surprising, but they’re not at all competitive with each other — they just want confirmation of their facts. Information is the coin of their realm. My hat is forever off to these folks.”

Interest among families of the missing endures, he said.

“Common wisdom used to be that as years went by, fewer and fewer would care about a missing relative from way back — family members’ memories would die out. But we’ve been pleasantly surprised that there has actually been a growing demand from families for us to work World War II cases. I think movies like Saving Private Ryan and books like The Greatest Generation and the World War II Memorial in Washington have had a lot to do with it. I do six or eight family information exchange meetings a year in cities all over the country, and World War II families are coming to talk to us in greater and greater numbers. They want to know what happened to Grandpa’s brother.”

Locating a set of remains is only part of the job. The DPAA also must be able to say with absolute certainty who the person was. The longer remains lie partly or fully buried in acidic or moist soil, the more they will degrade and become unidentifiable. But in recent years the reach of DNA screening has advanced dramatically, allowing, for example, extraction of usable DNA from extremely compromised remains. So Fennell and his colleagues put a lot of effort into soliciting family members to give a cheek swab for the cause.

The DPAA is charged by Congress with returning and identifying the remains of 200 missing service members a year, and the agency has been meeting the goal: The report for the fiscal year ending last Sept. 30 counts 140 recoveries from World War II, 73 from Korea and five from Vietnam, for a total of 218.

Related Story:

HISTORY AT WORK:

PROBING THE ARMY’S X FILES

Sarah Barksdale ’09 (MA, ’14 PhD) started her graduate studies assuming she’d become a university professor. After all, isn’t that what she was destined to do with her degree in 20th-century U.S. military history? Isn’t that what all Ph.D.’s do?

Well, no. And that’s how she came to jointly lead the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency’s program of disinterring unidentified remains from American cemeteries in Europe with Josh Fennell ’01.

More than half the identifications result not from field searches but from exhuming unidentified remains buried years ago in American military cemeteries with the label “Unknown” and examining them with updated research and current technology. A second part of Fennell’s job is overseeing the agency’s program of disinterring unidentified remains from Western European cemeteries — a post he shares with another UNC graduate, Sarah Barksdale ’09 (MA, ’14 PhD)

The agency operates with a staff of 600 — half civilian, half military — and an annual budget of about $150 million, which works out to three employees and nearly $700,000 for each story brought to completion.

“That’s a lot,” Fennell conceded. “But you know, not just as a DPAA employee but also as a taxpayer I say, so what? I’d argue every day of the week that this is part of the deal we make with people who wear the uniform.”

Positive identification

In the cornfield, Fennell and the team note scattered pieces of aluminum and plexiglass — small bits, nothing a farmer high on his tractor would notice, but they’re a good sign, and Fennell is happy. “There’s no reason for a piece of aluminum alloy or plexiglass to be in a field in France,” he says.

A collection of clamps from a B-26 Marauder. (Photo courtesy Josh Fennell)

The next day, they move to an adjacent field where the corn is still growing. The stalks stand well over 6 feet high and their moisture saturates the air among the rows, making work uncomfortable and slow. After three or four hours, having found only a few random pieces of metal, Fennell and the team check out a pasture across the road, find no airplane debris and return to the first field to make systematic metal detector sweeps.

Through two more days of intense surveying they turn up a concentration of aluminum fragments in one part of the field as well as metal pieces with numbers that match the typical markings on a C-47. They also find buckles of a paratrooper’s static line and a slide rule used on cargo planes. They flag them all, and the archaeologist catalogs the finds. Eventually they use up their full allotment of flags. “We always bring a few thousand, but we never have enough,” Fennell said.

By this time, he’s seen all he needs to draw a conclusion. “Once you start finding positive aircraft debris,” he says, “it’s time to email the bosses.”

MACR 7651 is assigned a tracking number, complete with coordinates. That puts the site on the list for a possible follow-up mission by a recovery team. If the mission is approved — and Fennell is confident it will be — that means a much longer visit from a much larger team. The return is likely to last 45 to 60 days with a crew of 20 or more, heavy on young, fit workers — usually military volunteers.

Recovery work, Fennell explains, is very physical, very repetitive, much more difficult than the preliminary survey. “I tend to not want to leave anything undone. We can do 10 hours a day, and I figure we can eat lunch at the site, so the work can be kind of taxing, but it’s nowhere near like hauling thousands of bucket loads of dirt 45 days in a row. I dug ditches when I worked construction, but today I can’t compete with a 22-year-old soldier.

Asked why Americans are still looking for their war dead 75 years later, Josh Fennell ’01 has a ready reply: “Because in the United States we never abandon a missing soldier.”

“They’ll use the map we make. They’re going deep, so they’ll have a small backhoe, but they have to carry soil in buckets to a screening site. The team archaeologist trains them to sift with the mesh screen and to recognize things of importance, to distinguish bone from rock.”

If the recovery team finds human remains, they have to let local authorities determine that the deceased isn’t one of their citizens. Then the U.S. Army collects the remains and transfers them to Ramstein Air Base in Germany for shipping home in a flag-draped box with a military escort, and the Armed Forces DNA Lab at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware takes over, hoping to make a match with a DNA sample collected from a family member.

It won’t happen swiftly. The DPAA has scheduled its recovery missions two years into the future. The agency sometimes partners with a university that runs a field archaeology program, a professional archaeology firm or a nonprofit group, which can cut the wait to a year or 18 months. The combined work of dozens of people over months and years is recognized every time a service member’s remains are returned to the U.S. and identified at last, producing hometown-paper headlines like “Their Father’s Plane Was Shot Down in WWII. This Weekend They Finally Buried Him.”

“The idea that we don’t leave fallen comrades behind is more than a cliché,” Fennell says. “Military who work with us, when they leave, say they feel a little more comfortable that if the worst happens to them someone will come to find them. I guess that’s a little morbid, but there’s no way to put a bow on it.”

Meanwhile, he and his group will carefully return the cornfield to the way they found it. They’ll ask local officials to forbid relic hunting in the area and ask the owners not to significantly alter the land before the DPAA comes back to excavate. Then they’ll load their equipment into a rented van and turn their attention to an incident known as MACR 3984. They head south to a site deep in Brittany, where four crew members went missing in a crash of a B-17. It’s been waiting to be found since May 29, 1943.

Dan Carlinsky is a freelance writer based in Connecticut.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.