A Subtle and Reflective Justice

Posted on July 23, 2020

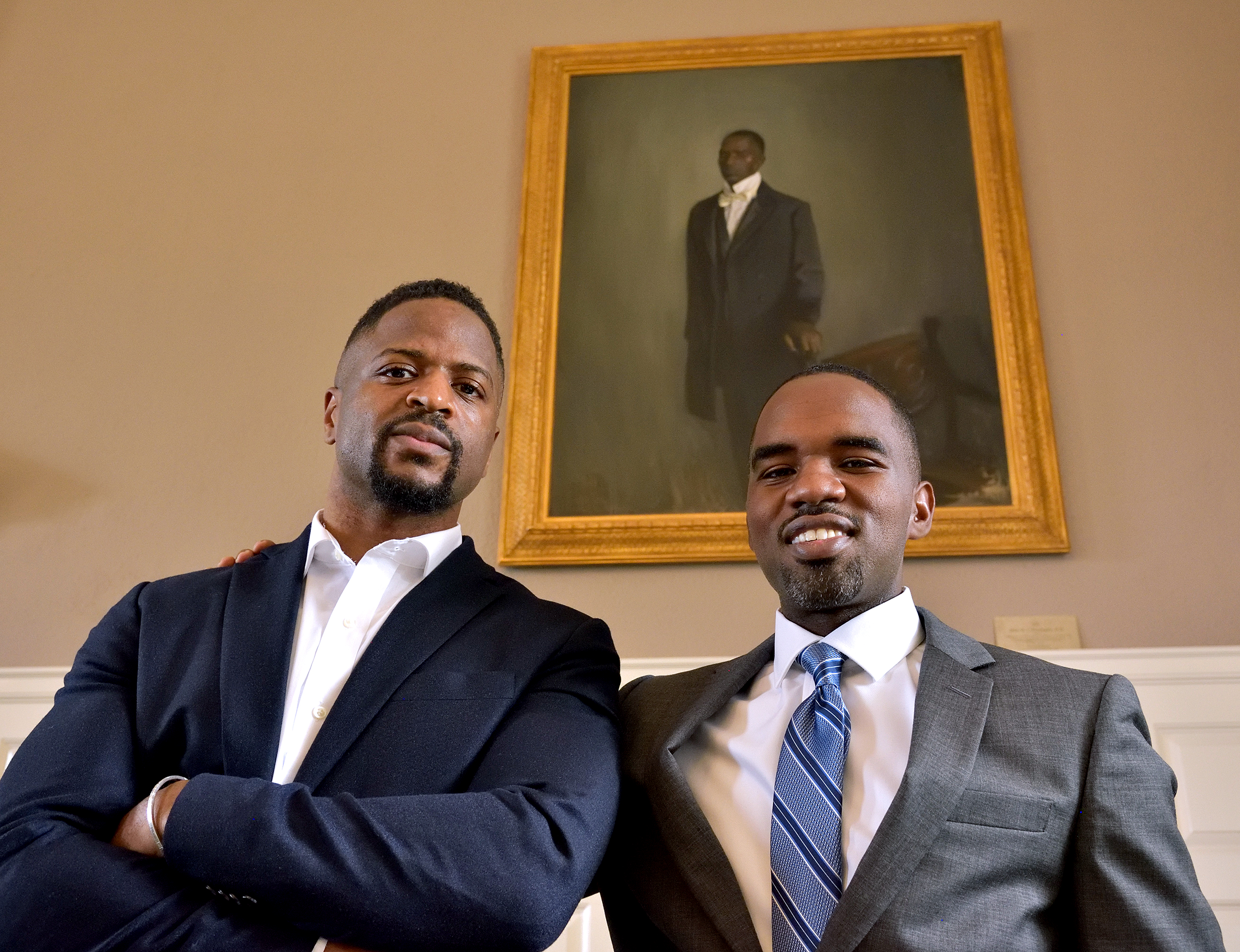

Elijah Heyward ’18 (PhD) has long been fascinated by historical memory in the South — what we honor and what we choose to bury. (Mic Smith/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review)

Cultural institutions helped raise Elijah Heyward ’18. Now he is lifting one up on the site of what has been called “slavery’s Ellis Island.”

by Eric Johnson ’08

It’s a measure of Charleston’s strangeness that the front door of Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, one of the oldest African American congregations in the country, opens onto Calhoun Street.

For 124 years, a towering monument to John C. Calhoun stood a block away, proclaiming the South Carolina statesman’s commitment to “Truth Justice and the Constitution.” Calhoun also was vehemently committed to slavery, states’ rights and Southern aggrievement. He would have been outraged at free Black people pouring out of Sunday worship onto his sidewalk. The city took down the monument in June, but the street name endures — for now.

Genuine charm obscures all manner of historical contortion in a city that welcomes millions of tourists each year. The Old Slave Mart Museum is an eight-minute walk from the Confederate Museum, which has been around since 1899 and still offers $5 tours. You can get married at restored plantation homes, take ghost tours that feature Civil War widows and enjoy Michelin-starred versions of field-hand grub from the antebellum era. “Our country’s past is very much still palpable in Charleston,” says Travel & Leisuremagazine. At least some of it.

Elijah Heyward ’18 (PhD) has long been fascinated by historical memory in the South — what we honor and what we choose to bury. The Beaufort, S.C., native came to UNC in 2015 because it seemed like the right place for doctoral research on the Gullah Geechee culture, unique to descendants of enslaved laborers who live along the coast of the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida. Heyward wanted a deeper understanding of his own heritage, the chance to explore and celebrate his home community in the lowlands of South Carolina.

“Where does the African American experience show up in history, especially in Southern culture?” Heyward asks. “I was interested in a university that could give me the tools to promote and preserve that.” He settled into UNC’s American studies department thinking he might become a professor, someone who interprets society and history for the next generation.

An artists’ renderings shows the completed museum on the site of Gadsden’s Wharf. (IAAM)

That changed when a radicalized racist named Dylann Roof walked into the centuries-old church on Charleston’s Calhoun Street, sat through a group Bible study, then shot to death nine of the worshippers who had welcomed him. Roof hoped to ignite a purifying race war, and he thought Charleston was the right place to do it.

Among those killed was the Rev. Clementa Pinckney, senior pastor of Emanuel AME and a South Carolina state senator. Heyward’s family knew him well. “Pinckney was a rock star, a hero figure,” Heyward recalled. “My entire life, my mom held him up as someone I should know and model myself after. For someone like me, it was really cool to have an example of public service that was tangible, that I could touch, that I had seen come up.”

Heyward went to Charleston to speak on a panel about the shooting, invited by a prominent Charleston philanthropist he met at Yale. It was there he ran into Mayor Joe Riley, who updated him on the new institution rising just off of Calhoun Street, the long-delayed International African American Museum. The project was a decadeslong crusade for Riley, a white progressive who first became mayor in 1975.

“Charleston is a city that has always accepted the responsibility of preserving and presenting its history, [but] there is one aspect of Charleston’s history that we have been quiet about presenting,” Riley said in a 2000 speech. “It is the history of African Americans — their life and role in our city and in the development of our country.”

After years of stalled progress, Riley told Heyward, a museum to share that history was moving forward. It was planned for the site of Gadsden’s Wharf, where hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans were forced onto the shores of the United States. The strikingly modern structure will rest on concrete pilings above the site, with huge windows looking out toward the waters of Charleston Harbor.

“Blackness, Black culture, the African experience, the African American experience, slavery — however you want to slice it — this is ground zero.”

— Henry Louis Gates Jr.

The historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. has described the place as “slavery’s Ellis Island,” estimating that 80 percent of the African Americans in the United States can trace an ancestor through that single point of entry in Charleston. “Blackness, Black culture, the African experience, the African American experience, slavery — however you want to slice it — this is ground zero,” Gates said.

Mayor Riley gave Heyward a business card and told him to keep in touch.

“Art makes you feel less alone”

Heyward came to UNC by way of Yale Divinity School, Hampton University in Virginia, and the many libraries, museums, art centers and family living rooms of his hometown in Beaufort, about 90 minutes down the coast from Charleston. He grew up surrounded by extended family, with deep ties to church, to school and to places like the Penn Center, a beacon of African American learning and culture that dates to 1862. His parents, Vernelle and Elijah, worked hard to surround their children with creativity and civic pride.

“Community, man — that means a lot,” his father said. “I wanted my kids to be around their grandparents. I wanted them to be raised in a small town before they go out in the big world.”

The younger Heyward still speaks to his parents daily. “We check in every day,” his mom said. “We just have a general conversation about what’s going on, what’s happening in his day. That’s just a normal thing for us.”

Heyward’s father was a high school social studies teacher and a member of the Air Force Reserve; he split his time between repairing warplanes and writing playful verses of original poetry for his students. Vernelle Heyward went back to college when both her children were young, which gave them early exposure to campus life. She worked in social services, overseeing youth education and job training programs, which she credits for early parenting insight.

The model of the museum, for which the COVID-19 pandemic barely slowed construction. It’s scheduled to open next year. (Mic Smith/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review)

“Working with other people’s children allowed me to be a good parent to my children,” she said. “You don’t realize what kids go through until you talk to them. A lot of kids can’t really talk to their parents.”

That was never an issue with Elijah. “The minute he got home from school, he’d just sit and tell me everything that happened, from when school started to when it ended; every little detail. He started his college research in the sixth grade.”

By the time Heyward was ready to apply to college, he had the grades and the extracurricular achievements to be competitive just about anywhere. He chose Hampton for its history and its connection to African American culture. “I always wanted to go to an HBCU,” he said. “Hampton was Southern. It was small enough but also big enough. It just really resonated with me.”

He immediately got involved with the Hampton University Museum and the school’s chapel. For Heyward, there’s an obvious link between art and faith, between cultural institutions and church. Both can cultivate a sense of belonging, offer a set of values, and give people a vision for how to live a full and meaningful life. In conversation, he moves effortlessly from quoting theologians to name-checking visual artists.

“Cultural institutions helped to raise me,” he said. “I’ve always believed that art makes you feel less alone. So much of life is communication, expression. You don’t just communicate through words — you communicate through actions, the way you move, what you choose to share.”

And what you choose to build. In an article for Yale Divinity School, where he earned his master of arts in religion after graduating from Hampton, Heyward said that creating an exhibit or a museum can be an act of “public social witness,” a way to bring biblical teachings to a broad audience. “Ministry not only happens on Sundays from the pulpit but by what we do beyond,” he said. “What happens to those who will never set foot in a church? How do we reach and serve them?”

A long-stalled project

It didn’t surprise Heyward’s mentors at Carolina when he decided to forgo the academic path, follow up on that conversation with Charleston’s mayor and take a position with the still-unbuilt International African American Museum. He became chief operating officer in August 2018, taking charge of the effort to turn a beautiful vision into a $100 million reality.

If he’s nervous to be overseeing a huge and sensitive civic project at the age of 37, Heyward doesn’t show it. In a three-hour discussion over dinner a few blocks from the museum site, he sounded more like a lottery winner than a man with one of the more politically, financially and morally complex jobs in Charleston. “Ten-year-old me would be doing cartwheels,” he said. “This is the culmination of a lot for me and my family.”

At Hampton, he founded a society to get students more involved in the university’s museum. At Yale, he founded a mentoring program that brought young African Americans to places like the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library or the Yale Center for British Art. He ran a summer academy for African American students that partnered with some of the biggest foundations, galleries and cultural institutions in Washington, D.C. At Carolina, he worked on exhibits at the Ackland Art Museum and made a point of bringing his undergraduate students into the galleries. Building a museum from the ground up feels like a fantasy job.

Heyward with the Charleston monument to Denmark Vesey, who purchased his freedom and worked for education and freedom for others. (Mic Smith/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review)

“Elijah is deeply spiritual, and that spirituality shines in his perspective,” said Glenn Hinson, the American studies professor who was Heyward’s dissertation adviser at Carolina. “To hear Elijah give a sermon at his home church is to realize that the community had a vision for him, and he saw his role as fulfilling that vision and offering it to those who came behind him.”

For the past few years, Hinson has taken some of his undergraduate students to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington. “The African American students treat that museum as a shrine. And the white students tend to step into it with a sense of wonder and new realization,” Hinson said. “I think this museum in Charleston has a very similar potential.”

Much of the Charleston museum’s power will come from its location. The history of Gadsden’s Wharf will inform every aspect of the museum’s design and content. With the museum perched on concrete pillars, the ground below will become an expansive memorial garden, including a tide pool that will empty to reveal the life-sized outlines of African men and women, contorted into the positions they might have held below decks on a ship crossing the Atlantic.

The museum will house the Center for Family History, a genealogical research institute focused on African American lineage in the United States. Visitors will have the chance to trace their own family trees and explore records like the pension files of the United States Colored Troops. There are plans for a dedicated Gullah Geechee exhibit, including a model of a traditional praise house like the ones where Heyward’s Low Country ancestors worshipped, and a recording booth where visitors can offer their own oral histories for the archive.

“This is a place where Black families will come to learn, will come to talk about roots, will come to reencounter the meanings of the Middle Passage and enslavement,” Hinson said. “And I think the white tourists who step into this museum are going to find themselves moved and changed.”

The museum’s progress is evidence that Charleston itself is moving and changing. The same horrendous crime that shifted Heyward’s plans also shook the South Carolina political world. Within days of the Mother Emanuel shooting, then-Gov. Nikki Haley responded by summarily removing the Confederate flag from the South Carolina statehouse. “The events of this past week call upon us to look at this in a different way,” Haley said. “A hundred and fifty years after the end of the Civil War, the time has come.”

The time finally came for Riley’s long-stalled project, too. State lawmakers gave their backing, and big donors got on board to show support for a grieving city. “This community could have decided to buckle, to take the path of hopelessness and despair,” Heyward said. “And instead they’ve rallied around projects like ours.”

The museum is scheduled to open next year.

The strikingly modern structure will rest on concrete pilings above the site of Gadsden’s Wharf, where hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans were forced onto the shores of the United States. (IAAM)

A glimmer of hope

In October 2018, Yale Divinity School unveiled a new portrait. Like every other piece of art in the grand and high-walled common room, it’s a gold-framed oil painting, looming over the students and faculty passing below. James W.C. Pennington stands straight-backed in the center of the frame, looking deeply serious in a formal coat and high collar, his hand grasping the back of a heavy curule chair.

The portrait is moody and sober, as you’d expect of an aspiring 19th-century minister. It blends perfectly with the 14 others in the room, except for one notable difference: James Pennington was a Black man, the very first to attend classes at Yale in the 1830s. And it took the better part of two centuries for Yale to decide his likeness deserved a place of honor on campus.

Heyward with artist Jas Knight at the unveiling of the James Pennington portrait at Yale. Heyward helped select Knight for the project. (Courtesy of Yale Divinity School)

“I remember my first time visiting this very room, as a visiting student,” Heyward said during the dedication ceremony. “I remember looking up at the walls and being really overwhelmed by the magnitude of the portraits but also looking for myself and not really finding it.”

It was Heyward who helped select Brooklyn artist Jas Knight to create the Pennington portrait. He had connected with Knight on Instagram, because Heyward is the kind of person who will drop an unsolicited message to an artist he likes. They bonded over art and scholarship, and Heyward kept in touch.

“Jas Knight is a friend of mine and someone who I deeply admire and respect for his commitment to his craft, but also, too, the way in which he approaches the idea of justice,” Heyward said at the ceremony. “I think that justice can be loud and can be in your face. But it also can be subtle and very reflective.”

That’s what the Pennington portrait achieves — a subtle and reflective justice. It quietly changes the space by resting so easily within it. Scanning the walls of the common room now, visitors might assume the Black theologian with the intense gaze has been there all along.

On a grander scale, that is Heyward’s hope for the International African American Museum. There is nothing subtle about a 42,000-square-foot commemoration of forced migration and cultural endurance on a prominent patch of Charleston’s waterfront. But the theory of change is not much different from the dignified oil painting Heyward commissioned at Yale. History that has deserved celebration will finally get it, taking its place among the stories and shrines that define the South. If it succeeds, the museum could become as much a part of Charleston as any genteel mansion or Civil War site.

“On the edge of the cobblestoned tourist area, with its ornate Gothic Revival-style churches and Queen Anne houses, the museum’s plain-spoken modernism comes across as almost whisperingly defiant, a turning of the page, promising a deliverance from history, modernism’s originating goal,” wrote New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman, reporting on plans for the museum in 2018. He referred to Charleston as a “Disneyland for the Confederacy,” in desperate need of a more honest identity. “Symbols matter. The past is present. The museum would clearly be good for more than just business.”

“I remember looking up at the walls and being really overwhelmed by the magnitude of the portraits but also looking for myself and not really finding it.”

—Elijah Heyward ’18

Heyward certainly thinks so. “People look for glimmers of hope, and the glimmer of hope here is this: By telling the unvarnished truth of slavery, but also wrestling with the fact that so many African Americans can trace their lineage to Charleston and to Gadsden’s Wharf, we expand what it means to be American. We expand the way history is taught.”

He is aware — painfully aware — that optimism can sound naive. He knows that many people are wary of uplifting promises, impatient with subtle and reflective approaches to justice. But he comes by his convictions honestly, as gifts from the people and the culture that made him.

“I was raised in a community of faith. You go to church, you go to Bible study — you’re bombarded with the notion that you’re serving God, that you’re serving a higher power who’s on your side. Regardless of what society throws at you, you’re going to make it. You’re going to be OK.”

Any true faith has moments of doubt, and Heyward has known some. There is a deep vein of grief in the dissertation he wrote at Carolina — mourning for Charleston, for the overlooking of Gullah Geechee culture, for the hardships that are living memories in his family. But the story he tells is focused on the contributions and achievements of people who shaped America from the beginning.

Those contributions keep coming. Heyward looks out of his temporary office on the Charleston waterfront and sees the earth moving, a long-deferred dream finally rising. All of those hopes and expectations so lovingly nurtured back home, faithfully carried to Hampton and Yale and UNC and now back again, are being made concrete.

“I was brought up with all four of my grandparents,” Heyward said. “These folks went through some real stuff. And never did they lose hope, never did they embrace pessimism, never did they suggest anything less than excellence was possible for me. They were my greatest teachers, and none of them went to college. This is for them, man. This is for them.”

Eric Johnson ’08 is a writer in Chapel Hill. He works for the College Board.