A Numbers Game

Hoping to meet an increasing demand from students,

Carolina launches its School of Data Science and Society

By Eric Johnson ’08

Data is everywhere at Carolina. Political scientists use sophisticated algorithms to analyze voting patterns. Journalism scholars use custom-designed code to glean insights from social media. Geneticists build computational tools to analyze DNA. Linguists use statistical methods to study vast amounts of text. Economists build predictive models with machine learning.

Over the next few years, at least some of that work will find a shared home in the School of Data Science and Society, Carolina’s first new professional school since the Institute of Government was upgraded to the School of Government in 2001.

Although the school officially launched this fall, Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz said in his July presentation to the University Board of Trustees that it will be 2024, at the earliest, before the first undergraduates begin enrolling in the new school.

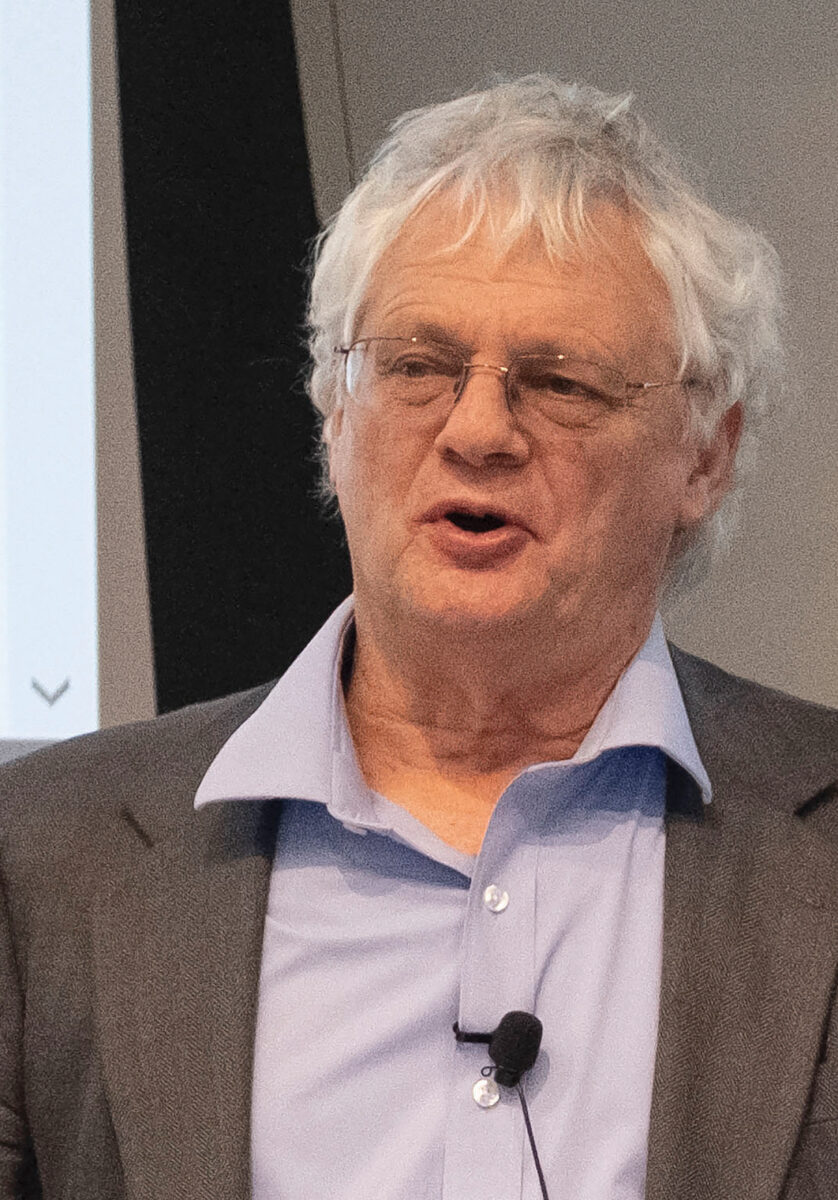

Stanley Ahalt, inaugural dean of the new data science school: “This is an opportunity for us to do something very transformative for the future of science and our society. A place where people can come together and intermingle and generate new research ideas.” Photo: UNC/Jon Gardiner ’98

Carolina’s data science effort has been almost a decade in the making, sparking debates about how the nation’s oldest public university should answer emerging workforce trends and respond to new technologies that reach across academic disciplines. Other universities have been quicker to embrace the “data science” label and cater to student interest in a fast-growing field, while Carolina has taken a more deliberative approach in deciding how big data will fit alongside traditional academic disciplines.

“This field of data science is changing so fast. It’s amazing how rapidly key techniques get shifted in just a couple years,” said Stanley Ahalt, who was named inaugural dean of the new data science school in June.

A computer science professor and director of UNC’s Renaissance Computing Institute, Ahalt said the study of data has evolved to the point that it deserves to be a stand-alone school. “This is an opportunity for us to do something very transformative for the future of science and our society,” he said. “A place where people can come together and intermingle and generate new research ideas.”

It’s also an opportunity for Carolina to catch up with competitors that have made big investments in data science, chasing student demand and employer interest in the burgeoning field. “I would say UNC is a little behind when you compare us to our peers, but we are distinguishing ourselves in the way we’re defining the school and the discipline itself,” said Jay Aikat ’09 (’10 PhD), a computer science professor and chief operating officer of RENCI. “The ‘society’ part [of the school name] is not an addendum. It’s at the very core of what we want the school to be.”

While UNC won’t be first to enter the data science realm, the University’s effort will focus on research that crosses academic boundaries, Provost Chris Clemens said. “We have incredible amounts of research in data science going on across the University,” he said. “We are already quite good at it, and truly world-renowned in some pockets.”

Clemens cited advances in health care diagnostics, increasingly complex energy grids and difficult questions around privacy and ethics as the kind of challenges the School of Data Science and Society might tackle. The school will coordinate the data research that faculty are already conducting and give students an easier way to see the breadth of data-intensive work occurring across the University.

“I think the data science school goes along with a commitment that every student, in the sciences or the liberal arts, knows something about how to interpret and manage data, in the same way that they need to know math and reading,” Clemens said.

Carolina’s data science effort has been almost a decade in the making. Other universities have been quicker to embrace the “data science” label and cater to student interest in a fast-growing field. Carolina has taken a more deliberative approach in deciding how big data will fit alongside traditional academic disciplines.

Meeting the market

“We are distinguishing ourselves in the way we’re defining the school and the discipline itself. The ‘society’ part [of the school name] is not an addendum. It’s at the very core of what we want the school to be.” — Jay Aikat ’09 (’10 PhD), computer science professor and COO of UNC’s Renaissance Computing Institute. Photo: UNC/Jon Gardiner ’98

The demand has increased as technology expands, creating a torrent of digital information that is outpacing the capacity to make sense of it. The Bureau of Labor Statistics rates computer and information research scientists among the fastest-growing occupations in America, with the number of jobs projected to grow 22 percent in the next decade. The agency notes Durham and Chapel Hill have some of the highest concentrations of data science jobs in the nation.

Claire Helms, a senior from Raleigh who is majoring in computer science and minoring in music, will be a good candidate for those positions. She’s been a web engineering intern for The Washington Post, helped analyze radio telescope data for the UNC astronomy department and served as a teaching assistant in computer science. “I came into UNC wanting to satisfy all these different parts of my brain,” she said. “I’m starting to understand how important data is to all of the different fields I’m interested in.”

Learning data analysis and programming has given Helms some assurance that she’ll find a solid career, whether that’s in journalism, education or astronomy. “I really want to do something I’m proud of and that is helpful to people,” she said. “I think part of the reason I loved computer science is because I was doing something I never thought I could do — and enjoying it.”

In appealing to students like Helms, UNC’s new school enters a crowded field. The University of California, Berkeley launched its Division of Computing, Data Science, and Society in 2019; the University of North Carolina at Charlotte has offered a master’s in data science since 2013 and launched its School of Data Science in 2020; and the University of Virginia’s School of Data Science opened its doors in 2019 backed by a $120 million gift — the single largest donation in UVA’s history. “The topic of data science is all around these days,” UVA President James E. Ryan told The Washington Post in 2019. “Some people might think it’s faddish, but it’s far from that. The explosion of data and the opportunities it offers across an enormous array of fields to me is nothing short of breathtaking.”

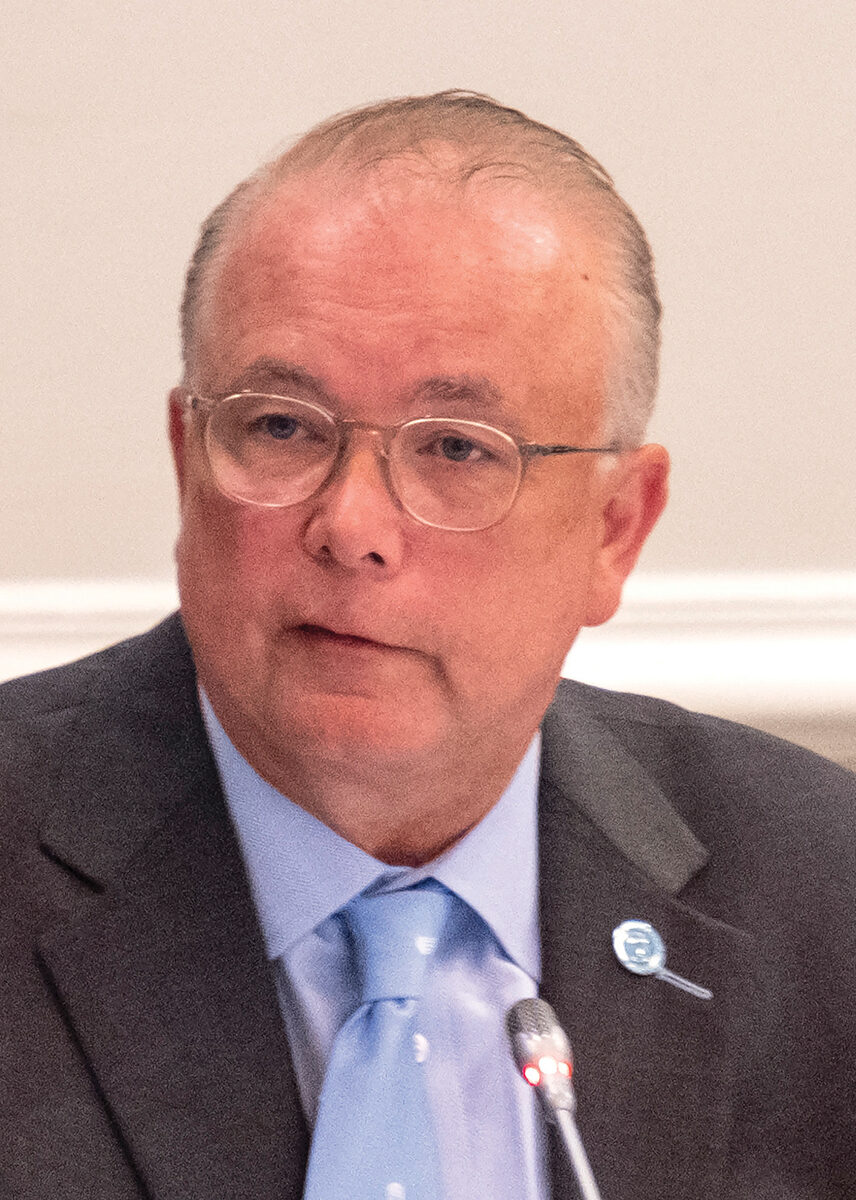

Board of Trustees Chairman Dave Boliek ’90 cited the strong job market when he endorsed the data science school during remarks at the January board meeting. “We cannot afford to wait, and the state of North Carolina cannot afford for us to wait,” he said. “With the increasing emphasis on technology and corporations finding North Carolina to be an attractive place to locate their business operations, we are charged with providing them with the workforce of the future.”

“I think the data science school goes along with a commitment that every student, in the sciences or the liberal arts, knows something about how to interpret and manage data, in the same way that they need to know math and reading.” — Chris Clemens, executive vice chancellor and provost. Photo: UNC/Jon Gardiner ’98

That future workforce doesn’t come cheap. Building out the new school is projected to cost tens of millions of dollars, and University officials asked state lawmakers to earmark $20 million in the latest budget to cover faculty salaries, new facilities and curriculum development. UNC got $1 million, which will mean a longer timeline for hiring new faculty and support staff — and more pressure on UNC’s fundraisers to bring in outside donations.

Nate Knuffman, UNC’s vice chancellor for finance and operations, said the school will take several years to scale up to the level envisioned by the University, with the pace partially dependent on additional state funding.

In the meantime, Knuffman said, Carolina is tapping unrestricted endowment funds and budget savings to pay for the initial school costs, such as leadership salaries and joint appointments for faculty in other disciplines. The school’s goal is to eventually graduate a thousand students a year, including undergraduates and master’s and doctoral students.

It’s likely to be several years before UNC reaches that benchmark. The first undergraduate and graduate students aren’t expected to enroll for another two years. Until more funding is secured, hiring of new faculty will be limited. Many of the professors who hold appointments in the School of Data Science and Society will be shared with other campus departments.

Competition for experienced data scientists in every sector of the economy has driven up salaries. Surveys by the N.C. Department of Commerce found that demand for data science talent extends from technology giants such as Apple and Lenovo to banks, consulting firms, hospitals and other high-tech manufacturers. A 2016 survey sponsored by the department and the National Consortium for Data Science called on the region’s universities to increase investments in data science education to help meet the demand.

Even UNC’s Office of the Provost is in the market for a data scientist, Clemens said, pointing to the need for more automated insight into the University’s complex budget and spending patterns. “Like a lot of places, we need to upgrade the tools we’re using to manage our data and analyze it,” he said.

The school’s goal is to eventually graduate a thousand students a year, including undergraduates and master’s and doctoral students. It’s likely to be several years before UNC reaches that benchmark. The first undergraduate and graduate students aren’t expected to enroll for another two years.

From politics to archeology

The first program planned for the new School of Data Science and Society emphasizes the market-driven focus of the initiative. The University is working with 2U, a for-profit, education technology company, to build an online master’s degree in applied data science, targeting the program to working professionals who are hoping for a career boost. 2U already administers and markets UNC-branded boot camps in coding, data analytics and technology project management. The programs last 18 to 24 weeks and are explicitly marketed as “industry-driven curriculum” tailored to accelerate career advancement.

2U has attracted controversy for the way some of its programs are structured. The company handles marketing, recruiting and customer service and even provides input on curriculum design. It also keeps more than half the tuition revenue. Clemens said the online master’s program will give the data science school a presence beyond North Carolina, and the University’s share of the revenue is intended to help fund the growth of the school.

The College of Arts and Sciences launched a five-course data science minor in fall 2021, cobbling it from a wide array of data-focused courses taught in different departments. Everything from “Data in Politics” (taught in the political science department) to “Laboratory Methods in Archeology” (taught in the anthropology department) can meet the requirements for the minor, with the goal of giving students a core understanding of coding methods, statistical analysis and the social and ethical questions around data.

The cross-disciplinary approach was spearheaded by Mariana Olvera-Cravioto, a professor in the department of statistics and operations research, who specializes in mathematical modeling and leads the data science minor. “We’re collecting data everywhere all the time,” she explained in an interview with Carolina Arts & Sciences magazine. “It’s something that more and more people need to know how to do, and we want students to not feel so intimidated by it.”

More than 360 students registered for the minor within a year of its launch, and 62 students who graduated in May had successfully completed the requirements.

For proponents of the new data science school, the role of information and analysis across nearly every discipline is a core strength for Carolina and a reason to bring diverse expertise together in a more-structured way. Data Science Dean Ahalt said the “pockets of incredible excellence” in data analytics that already exist across Carolina are a primary reason for creating the school.

He pointed to business school classes that emphasize market analysis, gene sequencing technology that relies on complex data models and computer-aided mapping to enhance archeology research. “The ubiquity of data and how much it is impacting all the disciplines is extremely important,” Ahalt said.

Angst about too much career-focus in higher education has accompanied the launch of every new professional school at Carolina. Edward Kidder Graham (class of 1898), who was UNC president from 1914 to 1918, used his inaugural address to defend the teaching of law, medicine and education as worthy of a great university. Changes to the curriculum always bring concerns about abandoning core disciplines in pursuit of new fads.

Is data a discipline?

“I think there’s always a tension between the idea that education is about providing information and technical skills versus gaining a holistic conception of human experience and human life — a broader conception that goes beyond specific information.” — Lloyd Kramer, history professor and faculty director of Carolina Public Humanities. Photo: UNC/Jon Gardiner ’98

Not everyone is convinced a separate school for data science makes sense. Andrew Perrin is a sociology professor who helped lead the revamp of UNC’s undergraduate curriculum, called IDEAS in Action, before joining Johns Hopkins University last year. The overhaul of the College of Arts and Sciences curriculum included debates among faculty about what students should learn by the time they graduate and which skills and experiences should be considered core to a Carolina education.

Perrin is an advocate for giving students more confidence in collecting and interpreting data, and the curriculum he helped champion includes a focus on quantitative reasoning and empirical research.

But separating those skills from specific academic disciplines is a mistake, Perrin said. “Students need the tools to do not just the technical analysis of data, but to understand where did the data come from, what data don’t we have and what questions are we asking or not asking?” he said. “I think those questions actually come through all of the disciplines, whether it’s comparative literature or biology or medicine. That’s where the big questions are going to come from.” Treating data as a stand-alone subject could give students an overly narrow way of thinking about data analysis, he said.

The broader academic world doesn’t agree on the definition of data science and whether it deserves to emerge as an independent discipline. A 2018 report from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine revealed a sense of ambivalence about how universities should organize the study of data and whether it makes sense as an independent field. “Data science is a hybrid of multiple disciplines and skill sets, draws on diverse fields (including computer science, statistics and mathematics), encompasses topics in ethics and privacy and depends on specifics of the domains to which it is applied,” the authors concluded. “The process of starting students down the path toward data acumen is a chief objective of data science education.”

Experience with coding and statistical analysis must be grounded in an engagement with art, culture, ethics and history, said Lloyd Kramer, a history professor and faculty director of Carolina Public Humanities. “I think there’s always a tension between the idea that education is about providing information and technical skills versus gaining a holistic conception of human experience and human life — a broader conception that goes beyond specific information,” Kramer said. “Technical knowledge of how a computer works or how accounting should operate may be part of that process, but it can’t provide that broader human framework that all students need to understand to be effective in the world.”

Angst about too much career-focus in higher education has accompanied the launch of every new professional school at Carolina. Edward Kidder Graham (class of 1898), who was UNC president from 1914 to 1918, used his inaugural address to defend the teaching of law, medicine and education as worthy of a great university. “It is not the function of the University to make a man clever in his profession merely,” Graham said. “It is also to make vivid to him through his profession his deeper relations — not merely proficiency in making a good living, but productivity in living a whole life.”

Changes to the curriculum always bring concerns about abandoning core disciplines in pursuit of new fads, Kramer said. He pointed to the debate in colleges at the end of the 19th century about whether to continue requiring Greek and Latin for all undergraduates. “This is one of the great characteristics of American universities, that they have these two strands of mission,” he said. “One strand is helping people gain the technical knowledge and skills they need in a modern industrial society. And the other strand is to give people the knowledge and perspective they need for a full and successful human life, which goes beyond their profession.”

Data Science Dean Stanley Ahalt said the “pockets of incredible excellence” in data analytics that already exist across Carolina are a primary reason for creating the school.

Not an either-or choice

“We cannot afford to wait, and the state of North Carolina cannot afford for us to wait. With the increasing emphasis on technology and corporations finding North Carolina to be an attractive place to locate their business operations, we are charged with providing them with the workforce of the future.” — Board of Trustees Chairman David Boliek ’90. Photo: UNC/Jon Gardiner ’98

University leaders acknowledge the pressure to deliver job-ready skills. Students now arriving on campus grew up in the aftermath of the Great Recession, which heightened anxieties about job security and created an expectation that Carolina provide a path into a stable career, Guskiewicz said. “It’s our job to deliver the right combination of breadth, depth and real-world experience for students by the time they graduate,” he said.

The leaders of Carolina’s data science program are confident they can resolve the tension. Ahalt said data literacy is increasingly important for democratic citizenship, given the role that algorithms and statistics play in public policy, journalism, law enforcement and a host of other fields. Making sure students know how to ask good questions and take a skeptical view of data should be a core goal for the University.

“I have a deep concern that we are vulnerable to the use of data as a persuasive tool of argument,” Ahalt said. “The story the data tells is just as important as the data itself. We need to create a principle on our campus where we’re going to have very data-literate students, so no matter what your degree is in, you’re going to understand how data can be collected and how it can be manipulated.”

Clemens, who is an astrophysicist by training and a longtime advocate of the classical humanities, said the University’s job is to help students understand they can follow their interests and still emerge with marketable skills. Offering a data science minor, or more interdisciplinary courses in data science, might help ease student anxiety.

“I think the tension is between what they’re passionate about and what they think will put food on the table,” he said. Students may come to Carolina passionate about drama or history or philosophy but decide they need to major in the sciences out of concern about job prospects. “But we don’t accept the either-or choice,” Clemens said. “You can major in history and still have a skillset that makes you successful and flexible.”

Eric Johnson ’08 is a writer in Chapel Hill. He works for the College Board, the UNC System and occasionally for UNC.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.