Bacterial Testing Breakthrough: Oysters Are Next

Posted on Sept. 12, 2019

Rachel Noble pioneered tests for bacteria that show results within an hour. Oysters are her new target. “If we’re going to expand the North Carolina shellfish industry and expand commercial growth of shellfish, guess what the primary use is going to be — raw consumption.” (Photo by Mary Lide Parker ’11)

Rachel Noble knows beaches, east and west. She played at the Jersey Shore on family vacations. Later, going to Southern Cal for graduate school put her in touch with the extreme human impact on the ecosystems of the world-famous beaches there — and the economic impact of contamination that could force them to close.

A bacterial problem on an ocean beach can flush away with the tide. But if the test for E. coli takes 24 hours to show results, you’ve lost a valuable day. Noble pioneered a DNA-based test that cuts the time to an hour or less. Swimming in that water is one thing; it’s quite another if the bacteria is in an oyster you’re putting directly into your mouth.

Noble’s new target is Vibrio — more complicated than E. coli and an enemy of the safe oyster consumption that’s vital to the North Carolina and East Coast seafood industry. The business has just gotten a growth boost from the state, and now oyster farmers, distributors and even restaurants are watching Noble’s lab.

“If we’re going to expand the North Carolina shellfish industry and expand commercial growth of shellfish, guess what the primary use of that shellfish is going to be — it’s gonna be raw consumption,” Noble said.

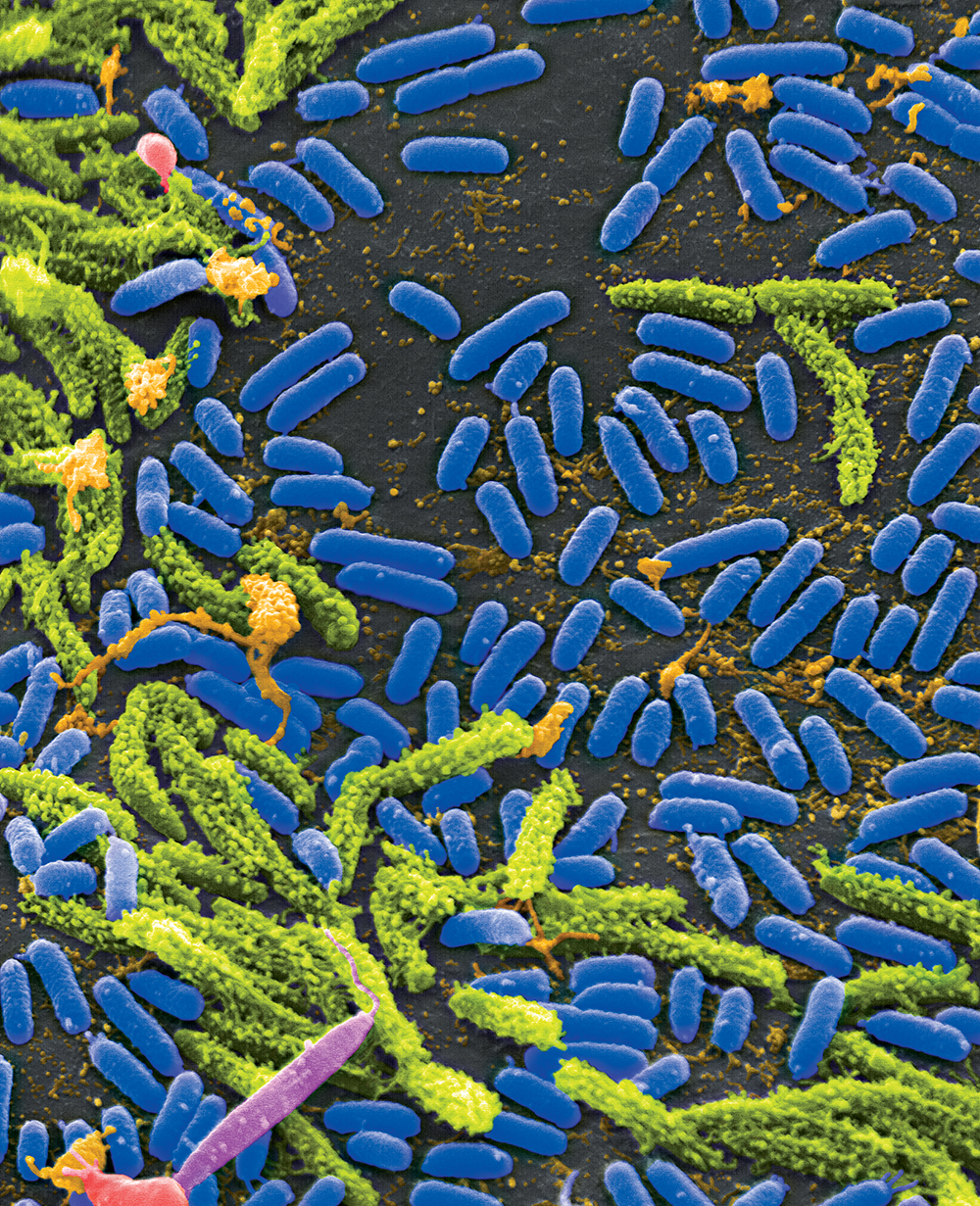

The N.C. General Assembly has approved legislation pushed by UNC’s and other marine labs to make it easier and faster for those interested in aquaculture to get started. Noble’s lab has signed an agreement to develop test kits that could be applied to oysters and used by state testing labs, oyster growers and food distribution companies. (iStock photo)

Between 95 and 99 percent of the oysters harvested from the state’s big farms go for raw consumption, she said. “So it behooves us to protect the industry by being proactive in terms of testing it, and we have the possibility to utilize these new tests — not only be proactive, but put North Carolina as an example of how you can do it even more quickly.

“It’s the exact same principle, but now it’s something that people are putting in their mouths. Now it becomes something really tangible. Almost everybody knows somebody who has eaten something raw, whether it’s seafood or produce or sushi,” and become ill. “So, what I call have your cake and eat it, too — you can actually have your fresh oyster, but you can actually have an oyster where you understand something about the risk associated with it.”

The Mary and Watts Hill Jr. Distinguished Professor had set out to study aerospace, then settled back to earth — among bacteria, good and bad, that have been the focus of a fruitful career in environmental microbiology.

Noble plied the California beaches. “They were already doing the math in their head,” she explained, “that if they had a test that takes two hours and you closed the beach at 8 a.m. and it was clean again at 10 a.m., we could actually potentially have that beach back open by 12 noon.”

California also is where the greengrocer’s wares grow. As with the water, Noble recognized the need for a way to reduce the time it takes to detect dangerous E. coli from a vegetable sample. A lot can happen in the 18 to 24 hours it takes to incubate bacteria with that sample, and she got it down to about 45 minutes using DNA testing. The critical breakthrough that helps protect people from potential illness came in 2004, four years after she arrived at UNC’s Institute of Marine Sciences.

The next challenge is practically a no-brainer. Vibrio loves oysters. Illnesses related to Vibrios are rare but can be deadly, especially to people who are diabetic or immuno-compromised. The industry is susceptible to alarmist reports of contamination and the damage a single account of bacteria-borne illness can wreak on social media.

“The Vibrios … are bizarre,” says Noble. “They can cause you to be infected two ways. There are almost no other bacterial pathogens that can do that.” (Photo by Tina Carvalho/Univ. Of Hawaii at Manoa)

Oystering has had its ups and downs, but the state’s lawmakers just gave the business more muscle. The N.C. General Assembly voted last spring, without a single nay, on legislation pushed by the Division of Marine Fisheries and crafted by marine scientists at universities, including UNC, to make it easier and faster for those interested in aquaculture to get started. It enables creation of shellfish “enterprise areas” of 20 to 40 acres in places where growing oysters has been successful and in which prospective growers could lease one to 10 acres — and it streamlines the permitting process in an industry marked by turf conflict.

Noble’s lab has just signed an agreement with Neogen, an international company that specializes in food safety testing and works in aquaculture, to develop test kits that could be applied to oysters and used by state testing labs, oyster growers and food distribution companies.

“The Vibrios — this is a really big deal to me — they are bizarre. They can cause you to be infected two ways. There are almost no other bacterial pathogens that can do that. If you have a cut in your skin, you can get a wound infection, and if you are immuno-compromised, that can kill you. If you ingest an oyster that actually contains enough of the bacteria, that can make you sick, and that can kill you.”

She works with oyster growers all over the East Coast, and she explained the advantage of rapid testing.

“It does need to be a two-hour test because if I’m a major seller and I’m going to harvest five tons of oysters for July Fourth weekend, and I have a testing program, I have a mechanism for protecting myself from a huge [bacterial] outbreak. I’ve got to know that within a couple of hours. You’re not gonna let your oysters sit around for a whole day waiting for a result.

“The aquaculture industry has already recognized that time to getting your product to where it’s going to be eaten is key to profit. The longer you hold onto it, the more that profit diminishes.”

Rapid testing for Vibrio also could have implications for the immediate aftermath of hurricanes that push salt water into North Carolina’s estuaries and increase the flow of stormwater down the rivers into them.

“It does need to be a two-hour test because if I’m a major seller and I’m going to harvest five tons of oysters for July Fourth weekend, and I have a testing program, I have a mechanism for protecting myself from a huge [bacterial] outbreak. I’ve got to know that within a couple of hours. You’re not gonna let your oysters sit around for a whole day waiting for a result.

“Vibrios are completely different from E. coli in that they don’t come from sewage or wastewater or humans,” Noble said. “They’re naturally found in the estuary. During a hurricane, all of a sudden the estuary gets a pulse of salt water from storm surge, and then the Vibrios start growing, and then you’ve got all this stormwater coming in [packing extra organic material], and then guess what — they just start growing like crazy.”

In that environment, measurement is not so important — scientists know the Vibrio will be present. But rapid testing could be important in letting people know when the water has returned to normal and in preparing for a storm.

“Prior to a hurricane event, during and after, people get exposed to a lot of maps that show them what the wind speed is, the size of the waves, what they can expect as far as storm surge and flood waters, and one of our biggest hopes is that we could begin the process of creating a Vibrio-response map. We can measure things like temperature and salinity and create a map where we expect risk to be high, and we can project that to the public to give them information about where there may be a concern for exposure.”

Noble is working now to expand rapid testing to other bacteria.

— David E. Brown’75

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.