Dorothy Espelage: Bullying Is Not a Rite of Passage

Posted on March 12, 2020

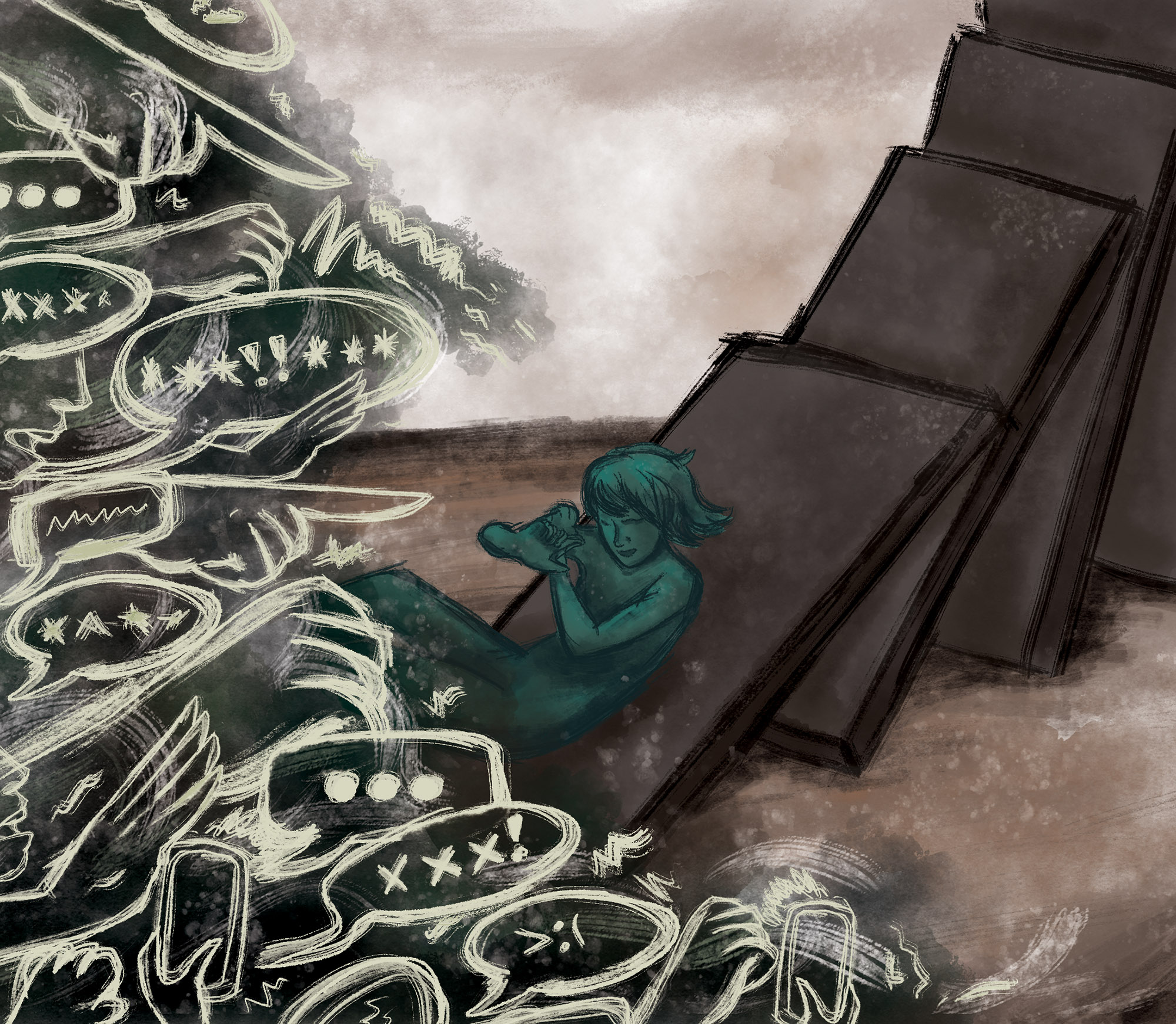

Anti-bullying “can’t just be a thing we do on Tuesdays or an assembly,” says Dorothy Espelage, the William C. Friday Distinguished Professor of education. “Expectations for behavior need to be part of the language, in the rubric, in the fabric of the school.” (Illustration by Haley Hodges ’19)

Back in October, midway through her first full semester of teaching at UNC’s School of Education, Dorothy Espelage returned from a short trip to China. Shandong Normal University convened one of the country’s first academic conferences on bullying, and Espelage was invited as a keynote speaker.

“They’re concerned about the continuing mental health issues with their kids, just like we are,” said Espelage, the William C. Friday Distinguished Professor of education. “They had read all of my work, which was very cool. I feel like I have a little bit of a reputation now!”

That’s underselling things a bit. A clinical psychologist with hundreds of research papers to her name, Espelage was invited to Shandong as the top bullying expert in the U.S., alongside leading academics in the field from Britain, Finland and Japan. It’s a distinction she’s earned over a quarter century of relentless campaigning to get school bullying taken seriously.

“China is not much further along than we were in the United States when I started out,” Espelage said. “They’ve done basic research on bullying for decades, but they’ve never taken it beyond that. They haven’t developed any programs, they haven’t begun to translate it into action.”

Espelage is an advocate of intrusive monitoring, especially for younger kids. “Talk, talk, talk. Know their friends, and watch the social dynamics.”. (Grant Halverson ’93)

Pushing for action — getting academic findings out of research journals and into the hands of teachers, parents and principals — keeps Espelage on the road.

Her China trip came on the heels of an 11-day visit to Colombia, where she met with leading researchers and policymakers about that country’s history of violence and trauma. But she’s just as likely to say yes to a PTA meeting, a newspaper interview or a quick soundbite for a morning talk show.

“I know it’s mostly my peers who are reading the 25 articles a year we’re doing,” she said. “The best way to disseminate to practitioners is to get in front of them and communicate research findings in a digestible, practical way.”

One of the points Espelage drives home in her talks and public writing is that bullying is no minor matter. The word gets used to cover all kinds of behaviors that sound much more serious when fully described. “Violence, sexual harassment, cruelty, racism — all of these things get blurred into the word ‘bullying.’ ” It’s been a careerlong battle to get policymakers and the public to realize that bullying isn’t an inconsequential rite of passage but a genuinely traumatizing experience for those who experience it and for many of those who commit it.

In a 2016 study, Espelage and her colleagues found that a history of being bullied was a significantly strong predictor of anxiety and depression in college — a stronger factor than even child abuse or neighborhood violence.

“I started studying bullying in 1993, and it took five years to get anything published,” Espelage said in an interview with the National Education Association. “I heard a lot of, you know, ‘What’s this about? Bullying is just part of growing up.’ Over time, we had to demonstrate that bullying was associated with adverse outcomes and show that over and over again. Now that we have these high suicide rates, we’ve been paying more attention to it finally. And now it appears that when you pack up your car for college, that history goes with you and has a significant impact on the way you adjust.”

That has led to much greater interest in the effectiveness of anti-bullying campaigns. Almost all states now have laws addressing school bullying and mandates for administrators to take student harassment seriously.

The quality of school programs to combat bullying still varies wildly, Espelage said. Figuring out how to create a healthier social scene for adolescents is tough; every school is different, and youth culture evolves quickly.

“But policy makes a big difference. And schools need to follow their own policies. When a kid reports being bullied, [schools] need to contact the parents. Parental support matters, and communication matters. A number of youth suicides would have been stopped if schools had just followed their own policies and called the parents.”

“When a kid reports being bullied, [schools] need to contact the parents. Parental support matters, and communication matters. A number of youth suicides would have been stopped if schools had just followed their own policies and called the parents.”

Schools also have to make anti-bullying efforts a baked-in part of the culture, something that’s included in the day-to-day curriculum. “It can’t just be a thing we do on Tuesdays or an assembly at the beginning of the year. Expectations for behavior need to be part of the language, in the rubric, in the fabric of the school. And really increasing parental involvement as much as possible.”

Her prescriptions will come as small comfort to adults already struggling to keep up with the explosion of digital communication among adolescents. The ubiquity of smartphones and social media has created new outlets for bullies and new sources of stress for parents who can barely track what their kids are doing online.

“Would you just let your kid go to an unlit park for a couple hours every night? Of course not,” Espelage said. “But you don’t know who they’re hanging out with when they’re gaming, when they’re on social media. And that’s a huge problem.”

She’s an advocate of intrusive monitoring, especially for younger kids. “Talk, talk, talk. Know their friends, and watch the social dynamics.”

Espelage and her colleagues are taking their own advice, closely analyzing peer effects to design better interventions. Figuring out which high schoolers have outsized influence may seem mystifying, but the potential benefit is huge.

“If I know that you have really high social capital and a lot of friends, then I want to train you. The hope is that we can use artificial intelligence and probabilistic analysis to figure out who in this high school needs to be trained, who has influence.”

Espelage already is working with the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health, local school districts and private-sector partners in the Research Triangle. That network of technology and health firms is part of what drew her to Chapel Hill, luring her from a well-established lab at the University of Florida.

“The last thing I wanted to do was up and move again,” she said. “Moving grants is a pain. But this is a dream job, to be in Chapel Hill, to be back in a School of Education. I like the way things are moving.”

—Eric Johnson ’08

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.