Harvey Miller: A Feel for the Music

Posted on Sept. 12, 2018

Harvey Miller ’58 (’61 MA) taught across the music spectrum at Brevard College, and he remains part of the music scene in western North Carolina. Not until

retirement did he have the time to delve as deeply as he wanted into the painstaking work of braille translation. (Photo by Eric Johnson ’08)

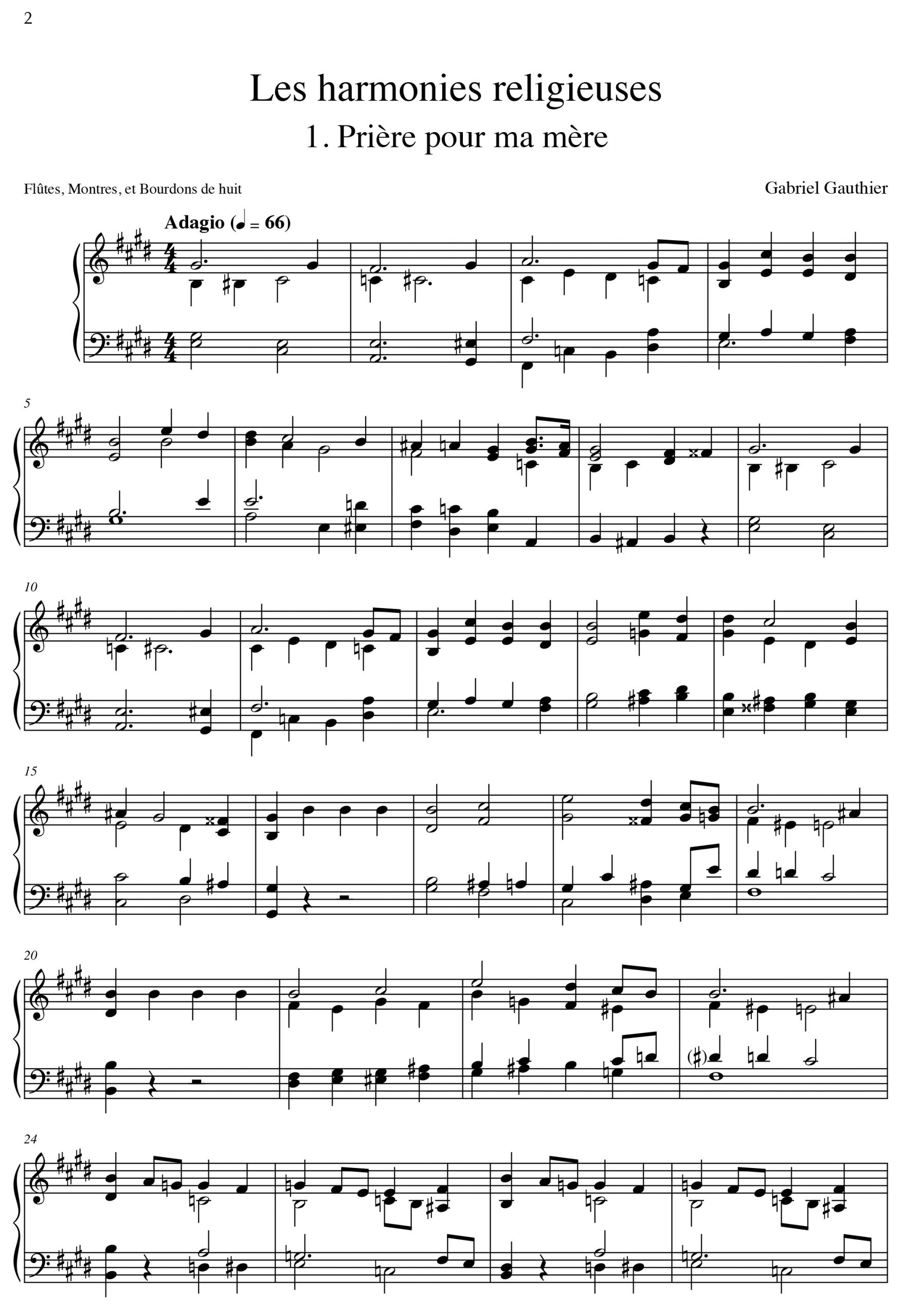

When the blind French composer Gabriel Gauthier died in 1853, most of his music went with him. Gauthier was a pioneer in braille composition and a well-known church organist in Paris, but little of his work was published in his lifetime. Even less of it survived the wars, revolutions and simple passage of time since the mid-19th century.

Now, thanks to retired Brevard College music professor Harvey Miller ’58 (’61 MA), some of Gauthier’s music is again echoing off church walls and gracing the shelves of music libraries. Through a chance discovery and a painstaking work of translation, Miller brought an original collection of braille music by Gauthier and three other blind composers into widespread publication for the first time.

“All of this music was being neglected,” Miller said, speaking in the living room of his home near the campus in Brevard. “It was valuable, and it’s something I felt the public should see. I wanted it available for everyone — and I’m very stubborn.”

Recueil de morceaux d’orgue (1863), A-R Editions Inc. (2017), edited by Harvey H. Miller ’58 (’61 MA)

That stubbornness served Miller well in the decadelong quest to bring the lost work into print. He discovered the fragile but well-preserved book of braille music during a visit to the American Printing House for the Blind in Louisville, where a museum displays hundreds of braille publications.

“Someone had donated it to the museum,” he recalled. “They just had it sitting there, along with other artifacts from early braille writers.”

Miller is a blind musician and composer with a scholarly interest in braille history, and he immediately recognized the significance of the book. “Gauthier wasn’t just an early composer of braille music,” Miller said. “He was Luis Braille’s roommate.”

The Royal Institute for the Blind in Paris, where Luis Braille refined his revolutionary system of reading and writing using raised dots, served as a unique kind of music conservatory. Students learned core subjects such as history and science, but they also trained as organists. Many went on to play in churches across Paris and to train new generations of musicians both blind and sighted.

Miller believes the recovered book of music — encompassing 54 pieces by Gauthier, Marius Gueit, Victor Paul and Julien Héry — likely was created for the school. “It’s music that’s typical of the 19th century, very romantic style,” he said. “I think it’s very good.”

Getting those 19th-century notes played again was a huge undertaking. The museum that housed the prized book wouldn’t let it leave the premises, so Miller had to make repeated treks to Louisville to do transcribing in braille before he could have it translated into a printed copy. He spent weeks living in a motel and working in a borrowed museum office.

Transcribing an aged braille text presents some unique challenges. Quite a few of the dots were pressed flat — the braille equivalent of ink faded from a page — which forced Miller to make his best guess about missing musical notes or instructions. “I didn’t notice some of the errors until I finally heard it played,” he said.

The equipment for transcribing also is bulky, not easy for even the most adept blind retiree to transport. Miller had to enlist the help of friends for the repeated trips to the museum.

“All of this music was being neglected. It was valuable, and it’s something I felt the public should see. I wanted it available for everyone — and I’m very stubborn.”

— Harvey Miller ’58

“It was very intense while I was doing it,” he said. “Eight a.m. to 4 p.m. every day, copying over this book by hand. I had to wait for retirement so I’d have the time to do it right.”

Even without the extraordinary restoration project, Harvey Miller’s musical devotion is hard to miss. There are three grand pianos in his living room, Brahms surging from the stereo, and a seeing-eye dog named Nita who greets visitors with a little singing of her own. The wood-paneled walls are lined with books of music and North Carolina history.

At Brevard College, Miller taught everything from classical piano to electronic composition. He worked with thousands of students over his career; led the school’s choral groups; played violin and piano in the Asheville Symphony; and continues to write short compositions as a gift to his wife, Adelaide Hart Kersh ’59.

It’s a life that grew from his own musical training at a young age, offered by the N.C. School for the Blind in Raleigh. In the century after the Royal Institute in Paris was founded, schools for the blind across the world adopted its model of blending traditional curriculum with intensive musical instruction and skilled trades.

“I learned to cane chairs, make mattresses, do woodwork, pottery, weaving, crocheting,” Miller recalled. “I figured I could make a living no matter what. I could continue in music, and if that didn’t work out, I could cane chairs!”

Now 84, he hasn’t had to do much caning. He and Adelaide, who also worked at Brevard College, are still fixtures of the music scene in western North Carolina, playing regularly in churches and other venues across the region.

One of the first performances of the recovered Gauthier work was at a church in Tryon, where Miller and Adelaide played a selection. A recording of the session amply captures the soaring quality of the music, but Miller likes to imagine it as Gauthier and his contemporaries might’ve heard it.

“He played in a huge stone church, Saint-Etienne-du-Mont in Paris,” Miller explained. “I can imagine it just rolls around in a place like that.”

Copies of the restored work are now in academic libraries all over the world — including at Carolina, where Miller donated one — so there’s a chance it’ll make its way back into a grand cathedral one day.

Miller would love to hear that. But even more, he’d love to visit the school in Paris where it all began, now called the National Institute for Blind Youth.

“I’d like to go stomp around in their basement and see if they have any more Gauthier music sitting around.”

— Eric Johnson ’08

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.