Have a Good Listen

Posted on Nov. 12, 2021

(Photo: UNC/Johnny Andrews ’97; Illustration: Jason D. Smith ’94)

The quality of public debate has become the debate. The Program in Public Discourse seeks to lower the temperature and raise democratic citizenship among students.

by Eric Johnson ’08

Heading into her sophomore year at Carolina, Sinclair Holian has a lot on her mind. “I feel like every class I’m in, we kind of end on this notion that we’re in a downward spiral, and what are you going to do about it?” said Holian, a journalism major from Greensboro.

“Climate change, social justice, COVID — I try to be cautiously optimistic about everything, but it’s a lot to put on a student just coming into college, to be like, ‘You better save democracy some day!’ ”

Fortunately, Holian is game to try. She’s among the first cohort of Agora Fellows at UNC, a group of civic-minded undergraduates who are part of the University’s Program in Public Discourse, launched in 2019 to strengthen students’ capacities for deliberative debate, with a goal of enabling them to serve as better citizens, civic leaders and stewards of democracy. The program is hosting public debates, offering training in classroom discussion and recruiting undergraduates for extracurricular discussion circles on everything from policy reform to vaccine policy. The students and faculty involved in the program come from different backgrounds and different political perspectives and have very different ideas about how to save democracy, solve climate change or improve race relations. They share the conviction that any effort to fix America’s big problems has to begin with talking to each other.

“I look on social media, and I see the same post about the same controversy circulated dozens of times,” Holian said. “It’s a lot of people with the same idea, the same perspective, sharing the same post. The Agora Fellows is having people from different majors, from different opinions come and hash out ideas and build on each other. It’s way, way different.”

“Large majorities say the tone and nature of political debate in the United States has become more negative in recent years — as well as less respectful, less fact-based and less substantive,” reports the Pew Research Center. And that was before the COVID pandemic, a summer of racial justice activism and unrest, and a contested presidential election.

Americans at all ages are struggling with political discourse and craving something different. “Large majorities say the tone and nature of political debate in the United States has become more negative in recent years — as well as less respectful, less fact-based and less substantive,” reports the Pew Research Center. And that was in 2019, before the COVID pandemic, a summer of racial justice activism and unrest, and a contested presidential election.

“People’s everyday conversations about politics and other sensitive topics are often tense and difficult. Half say talking about politics with people they disagree with politically is ‘stressful and frustrating.’ ”

“We come to college to be challenged and push one another, and that requires charitable listening. It’s really about the culture of a college classroom.”

“We come to college to be challenged and push one another, and that requires charitable listening. It’s really about the culture of a college classroom.”

—Sarah Treul, associate professor of political science

That presents an acute challenge for universities, which are supposed to be havens for productive dialogue across difference. “One of the things I love about teaching at UNC is that we have a very diverse student body, including politically,” said Sarah Treul, an associate professor of political science and the faculty director for the PPD. “We come to college to be challenged and push one another, and that requires charitable listening. It’s really about the culture of a college classroom.”

Charitable listening can feel like a dying art in American public life, and that has led a number of colleges and universities in recent years to establish programs aimed at promoting civic virtue. Educating democratic citizens has been a core part of UNC’s mission from its founding — what the University’s charter calls “an honorable discharge of the social duties of life.” But figuring out what that means in a sharply partisan environment, and with social media technologies that can turn an errant classroom comment into a national controversy, is pushing many campuses to rethink their approach.

“I think a lot of institutions are trying to be more direct about it, more explicit about viewpoint diversity,” Treul said. “These problems are not isolated in one university or one state. They really are global issues. Some of the new programs are linked intrinsically in their mission to promoting democracy, and others are more like ours at Carolina, focusing on discourse and communication as a precursor or necessary condition for democracy.”

Taking the contrarian view

The Program in Public Discourse is still new — its first full-time executive director, communications assistant professor Kevin Marinelli, was hired in 2020 — but it has already hosted a dozen public debates on everything from the minimum wage to the future of meritocracy, trying to model the kind of calm, evidence-based discussions that most professors hope to create in the classroom.

“I think that intellectual diversity is a really important issue in American higher education generally and at UNC in particular,” said Molly Worthen, an associate professor of history who serves on the PPD advisory board and has moderated a few of its public debates. “I’ve been worried for a number of years that the boundaries on ideas and discussions on our campus are narrower than they should be. We as faculty believe we’re doing a good job of creating an environment that’s welcoming and open to energetic discussion, but we’re actually not succeeding as well as we think we are.”

One of the PPD’s core aims is training faculty in how to encourage better discussions. Too often, professors report students sitting silently whenever controversial topics arise or watching as a handful of strident voices dominate the classroom — the same dynamic that plays out online. “What you have is kind of a social situation in the classroom that you have to break through,” said Chris Clemens, an astrophysicist and senior associate dean of research and innovation in the College of Arts and Sciences.

The University’s Program in Public Discourse launched in 2019 to strengthen students’ capacities for deliberative debate, with a goal of enabling them to serve as better citizens, civic leaders and stewards of democracy. The program is hosting public debates, offering training in classroom discussion and recruiting undergraduates for extracurricular discussion circles on everything from policy reform to vaccine policy. (Photo: UNC/Jon Gardiner ’98; Illustration: Jason D. Smith ’94)

“Students sense that there’s a social cost to speaking up, and it’s just not worth it. It’s better to keep your head down.”

Clemens was heavily involved in developing the PPD, and he continues to serve on its advisory board. He has been a lightning rod for criticism from colleagues over the years, in part because of a willingness to sponsor controversial student groups.

“I always err on the side of letting students have their go at it,” Clemens said. “If we’re not the right place for this, then shame on us. We haven’t constructed a social and educational atmosphere that prepares students for democracy.”

For Clemens, the critical skill for productive dialogue should be inhabiting a contrary position, learning to argue for a viewpoint you don’t actually hold. “That’s the key exercise,” he said. “That’s the only way you’re going to test your own preference. That was always the goal of good debate programs, but it’s very hard to do in a big classroom.”

“I’ve been worried for a number of years that the boundaries on ideas and discussions on our campus are narrower than they should be.”

—Molly Worthen, associate professor of history

Emily Greaves, a senior who participates in the Agora Fellows discussion groups, said she appreciated the focus on arguing from the opposite view. “It’s such a good thought exercise to go through. At the very least, you can figure out if you really believe what you believe,” she said. “I identify as a left-leaning student, and I find really genuine people in this program, and I’ve really enjoyed my time.”

She pointed out that public discourse is all the more important on a campus that seems to generate an outsized share of controversies worth talking about. In the nearly four years Geaves has been a student, Carolina has made national news for the Silent Sam showdown, the campus’s aborted pandemic reopening in fall of 2020 and the tenure controversy surrounding Nikole Hannah-Jones ’03 (MA).

“Most of my friends at other schools are not in the headlines every other week,” Greaves said. “My family sends me random articles they read in The Washington Post about UNC. So the ability to talk about things that are relevant and in the news is kind of important.”

Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz has made a similar point about the obligation of public universities to lead the way in welcoming and teaching public debate. “The genius of America has always been its capacity to welcome strident voices without tearing itself apart, to provide the framework and the forum for working out real differences without breaking the bonds of affection that hold us all together,” he wrote in a September newsletter. “A quiet campus, a place with no loudly dissenting voices and no contentious debates, wouldn’t be doing its job.”

By that measure, at least, the Program in Public Discourse has been doing its job from the very beginning. When the program was formally proposed in 2019, dozens of faculty members signed resolutions, letters and op-eds objecting to its origins and aims. “The development of the Program for Civic Virtue and Civil Discourse has been going on behind closed doors in administrative offices for two years,” read a resolution introduced to the Faculty Executive Committee. “What little the faculty have been told about it, however, is disturbing.”

Diversity or intrusion?

The nascent program was seen, at least among a sizable group of professors, as a way of circumventing the usual faculty channels to get more conservative voices and viewpoints onto campus. Similar programs at Princeton and Arizona State ignited debate about political intrusion into higher education, and faculty pointed to the UNC System Board of Governors as the driving force behind Carolina’s program.

“UNC faculty do not need external faculty or BOG and BOT members telling us what to teach or how to shape our campus culture,” wrote history professor Jay Smith and women’s and gender studies associate professor Karen Booth in The Charlotte Observer. She and 85 other faculty members called on administrators to either scrap the program or put it firmly under faculty control.

“Administrators worked in secret because the ideas behind the program were incubated far away from faculty.”

There’s little question that early discussions about the program were driven by voices beyond campus. Robbie George, a prominent conservative law professor and director of Princeton’s James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions, delivered a presentation to the Board of Governors in 2017 after then-Chancellor Carol Folt and then-UNC System President Margaret Spellings traveled to Princeton to learn more about the Madison Program.

“I always err on the side of letting students have their go at it. If we’re not the right place for this, then shame on us. We haven’t constructed a social and educational atmosphere that prepares students for democracy.”

“I always err on the side of letting students have their go at it. If we’re not the right place for this, then shame on us. We haven’t constructed a social and educational atmosphere that prepares students for democracy.”

—Chris Clemens, physics and astronomy

“There is a perception, and I believe also a reality, that the ideological balance may be a little out of whack,” Spellings told The News & Observer after the Princeton visit. “Have we created environments where people with all points of view can be heard and respected? … Obviously this is kind of a major issue of our time, how we talk to each other.”

Joe Knott ’74 (’80 JD), an outspoken Raleigh lawyer who was a BOG member at the time, declared that Carolina was becoming an intellectual monoculture and needed a concerted effort to promote diversity of thought.

“We are trying to address a problem that seems to be endemic in higher education all across the United States,” Knott said at the time. “Of course, it would be a wonderful thing if you’re a liberal student, rather than going to Yale and having everybody agree with you, you could come to Carolina and get a very fine liberal education but you would be challenged at every point by the best conservative scholars in the country.”

Knott’s rhetoric may have infuriated some faculty, but it contains at least a grain of truth. Faculty at top-tier universities, including Carolina, do lean left, especially in the humanities. Whether that constitutes a problem — whether it skews classroom debate or chills student speech — is a separate question. “Are our students being taught by Republicans or Democrats? I just don’t think that’s what viewpoint diversity should mean on a college campus,” said Mimi Chapman ’97 (PhD), professor of sociology and chair of the faculty.

“I just think it’s sort of a false argument. I think you have to define your terms better. What does viewpoint diversity really mean when you’re talking about an academic discipline?”

There have long been allegations from conservative lawmakers and news outlets that right-leaning voices are underrepresented or actively suppressed at Carolina. “It is alienating to be a conservative in Chapel Hill. In many of my classes, the word ‘Republican’ holds the same weight as the word ‘Duke’ at best or ‘racist’ at worst,” wrote senior Patterson Sheehan in a February column for the James G. Martin Center, a right-leaning advocacy organization that frequently criticizes UNC for political bias.

“In the name of a liberal arts education, professors and the student body ought to applaud genuine diversity of thought. Instead, they stigmatize it.”

Clemens said most of his faculty colleagues don’t see a troubling absence of ideological diversity on campus because they exist within a comfortable consensus. “What the faculty think is that they don’t have an ideology. That anyone who disagrees with them is somehow ill-informed and an ideologue,” Clemens said. “If you’ve cast yourself as the mean of the reasonable, rational position, of course you don’t think you have a viewpoint diversity problem.”

A fear of peers

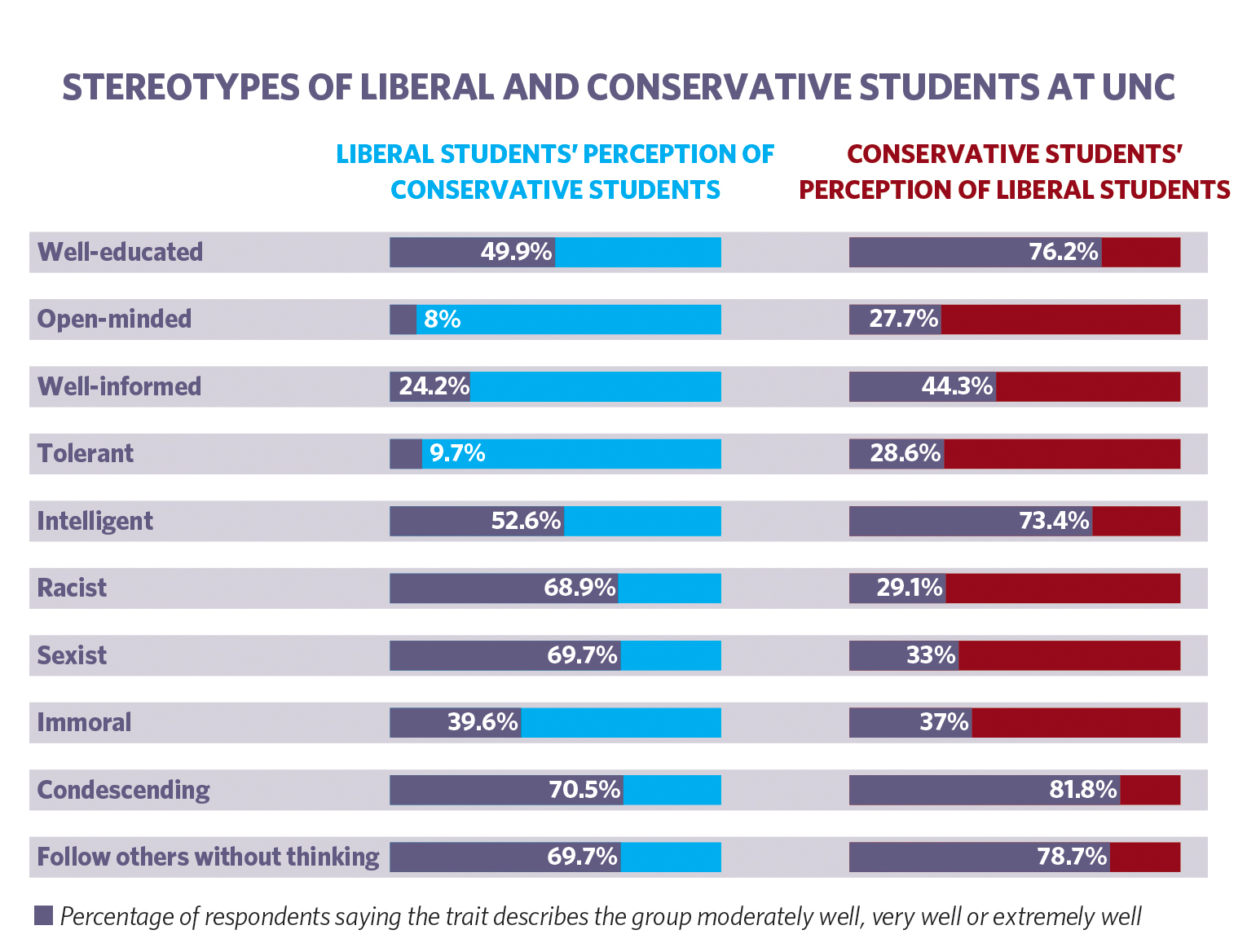

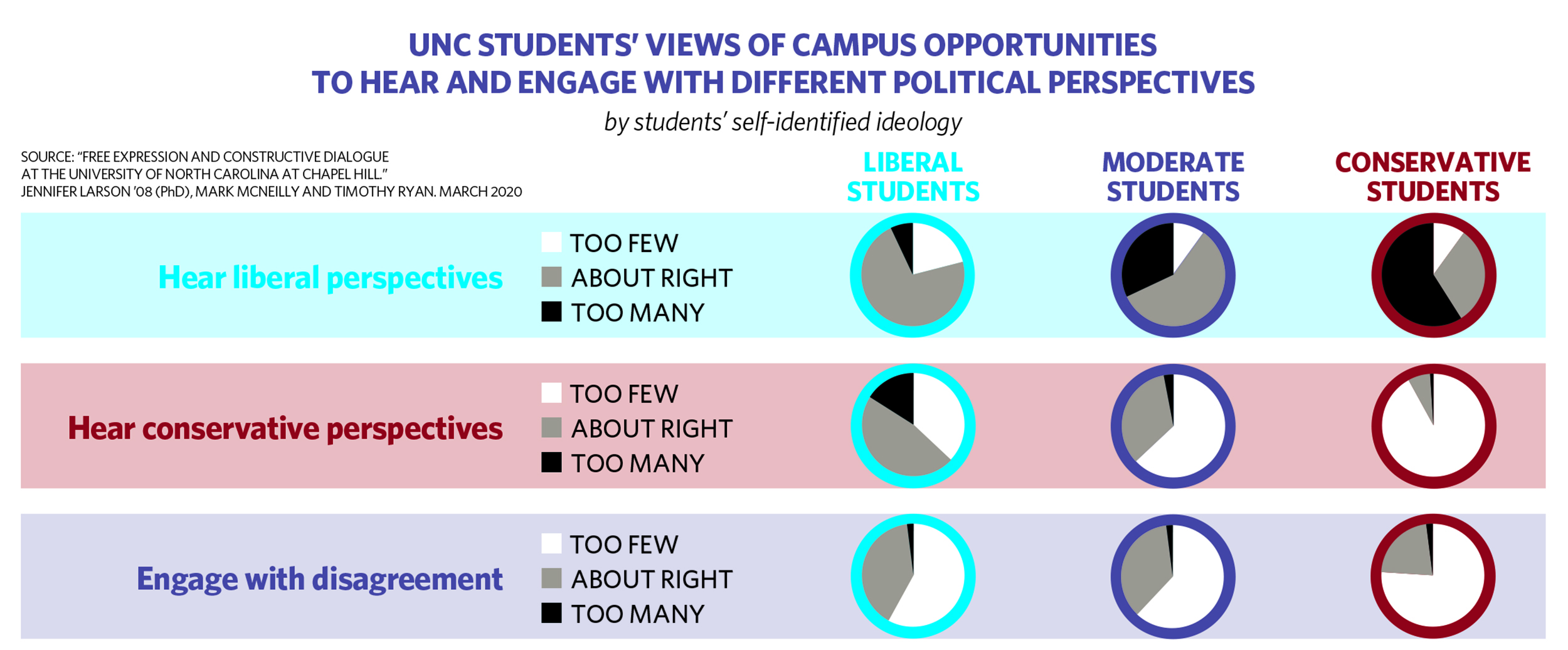

In 2019, a group of UNC researchers set out to answer some of the fraught questions about the political culture on campus. Using a rigorous set of survey techniques pioneered in political science, three scholars — Tim Ryan in political science, Mark McNeilly in the business school and Jennifer Larson ’08 (PhD) in English and comparative literature — queried more than 2,500 UNC undergraduates about their experience of politics and dialogue on campus, including whether students felt professors pushed partisan viewpoints in the classroom. The results didn’t fit neatly into anyone’s favored narrative about political bias.

“Almost any table in our report, you could make conservatives happy or liberals happy,” Ryan said. “There’s a lot of nuance to it.”

What Ryan and his colleagues found was that students do perceive a clear leftward slant to the overall campus environment, but they don’t feel much political pressure from the faculty. Instead, it was a fear of censure from their own classmates that drove anxiety and self-censorship among students.

In 2019, a group of UNC researchers set out to answer some of the fraught questions about the political culture on campus. The results didn’t fit neatly into anyone’s favored narrative about political bias.

“Instructors do not regularly offer political opinions, and even when politics comes up, most instructors are perceived — even by students who identify as conservative — as encouraging participation from liberals and conservatives alike,” the survey found. “Another important insight from our report is that, compared to students who self-identify as liberal, self-identified conservative students do in fact face distinct challenges related to viewpoint expression at UNC. Several of these relate to peer judgments and sanctions, rather than faculty behavior. Self-identified conservative students are more concerned about censure for expressing their views.”

The researchers also found that almost all students, including large majorities of self-identified liberals, were hungry for more productive engagement across ideological lines. “We were pleasantly surprised to find out that for the most part, there were large segments of students who want to reach out and hear from their political opposites, who wanted to have constructive dialogues,” McNeilly said. “But you can’t just say, ‘Go out and have a constructive dialogue.’ You need to give students the tools to do that.

“Because when they get out into the real world, they’re not going to be in a classroom with 30 other people having their conversation moderated. They’re going to be having these discussions across the dinner table or on social media. They need the skills to take some positive actions, not just unfriend people.”

“You can’t just say, ‘Go out and have a constructive dialogue.’ You need to give students the tools to do that. … They need the skills to take some positive actions, not just unfriend people.”

“You can’t just say, ‘Go out and have a constructive dialogue.’ You need to give students the tools to do that. … They need the skills to take some positive actions, not just unfriend people.”

—Mark McNeilly, Kenan-Flagler Business School

Greaves, the senior participating in the Agora Fellows program, echoed that sentiment. “I think a lot of students do self-censor themselves in the classroom. We’re also trying to make friends on campus, and no one wants to be overtly political when they don’t need to be,” she said. “But I think for the most part, students are growing as thinkers and as speakers and as people who want to be evidence-based when they talk about things. The question is how do we foster that in the classroom, on social media pages and elsewhere?”

Greaves has been “tinkering around with a pre-health, pre-med” career path, she said, and she talked about applying the lessons of public discourse to science communication.

“I think there’s more of a focus on how you can stand up for your science and argue it in a way that’s really effective.” She pointed to an Instagram account — @whereyallgoin_unc — that aimed to publicly call out students who were defying pandemic restrictions over the last year. Shaming may feel satisfying and rack up social media clicks, but it’s not very effective at changing minds. “There’s the science, and then there’s the reality of public health communications,” Greaves said.

That’s exactly the kind of real-world application that PPD advocates hope for when they encourage classroom discussion. “Our initial focus is on the classroom, but the classroom is not an isolated environment,” said McNeilly, who serves on the advisory board. “You’re seeing what’s happening in class, but there’s a whole bunch of stuff happening outside of class that you’re not seeing.”

There are still plenty of PPD skeptics, but Marinelli says the proof of good intentions will come over time.

“We made the decision somewhere last year that the best strategy we can take is just to do good work and let the work speak for itself. Some people may need to be convinced, and that’s great. Let’s focus on the work we’re doing with the allies we have and let other people come to the table as they recognize it. I think most people are going to be pleased, or at least challenged in the right ways.”

Worthen is also taking the long view, hoping that a prominent effort at good-faith debate will help cool some of the heated rhetoric about bias and conservative alienation from higher education. “As a historian, I try to remind myself that the narrative of the university as a den of socialist elites who are out of touch with the heartland, that goes back 150 years, at least, in this country,” she said. “I don’t believe one program can rebuild trust after all of this, but I don’t think it’ll hurt.”

In September, Worthen moderated the PPD’s first major event of the fall semester, bringing together experts in psychology, social media, political science and history to try to find a little hope for the future of American self-government.

“It’s easy to feel right now like you’re drowning in lots of terrible stuff you can’t control,” she told the students in the audience. But if they embrace the University’s mission of thoughtful reflection and a patient search for truth, they can navigate it. “It’s the one hope to assert some order over the chaos.”

Holian, the sophomore aiming for a career in journalism, is doing her best to follow that advice, despite the “doom and gloom” that seems to dominate political conversation. “It really feels like we’re in a burning building, trying to frantically put out this fire,” she said, referring to the country at large. “It feels like it’s real life, not just a scholarly discussion. People really care, so hopefully we can pull it off.”

Eric Johnson ’08 is a writer in Chapel Hill. He works for the College Board.

SURVEY SAYS

Here are the principal findings of a 2019 survey of more than 2,500 Carolina undergraduates by UNC researchers Jennifer Larson ’08 (PhD), Mark McNeilly and Tim Ryan.

30.8 percent of students feel they have become more liberal during their college years. 15.9 percent feel they have become more conservative. 47.8 percent feel their ideological leanings haven’t changed. ■ In most classes, politics rarely comes up. ■ Students generally perceive course instructors to be open-minded and encouraging of participation from both liberals and conservatives. ■ Students almost ubiquitously perceive political liberals to be a majority on campus. ■ Both liberal and conservative students worry about how students and faculty will respond to their political views, and students across political perspectives engage in self-censorship. ■ Anxieties about expressing political views and self-censorship are more prevalent among students who identify as conservative. ■ Students worry more about censure from peers than from faculty. ■ Students harbor divisive stereotypes about one another. ■ Students across ideologies report commonly hearing disparaging comments about political conservatives. ■ Many respondents are open to engaging socially with students who don’t share their political views, but a substantial minority is not. ■ Approximately 19 percent of self-identified liberals and 3 percent of self-identified moderates and conservatives endorse blocking a speaker they disagree with. ■ Students across the political spectrum express interest in having more opportunities for constructive dialogue — in particular, conversations that include conservative speakers.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.