He’s Not Broken

Posted on Jan. 21, 2022

(Alyssa Schukar/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review)

Eric Garcia ’14 thrived after accepting his autism. He wants the world to give all autistic people the same chance.

by Beth McNichol ’95

As a teenager in Southern California, Eric Garcia ’14 began encountering media messages that implied he needed repair.

He watched former Playboy model Jenny McCarthy share with CNN’s Larry King the now-discredited and retracted theory that childhood vaccinations cause autism. Around the same time, a vast lineup of Garcia’s rock heroes appeared in a public service announcement on VH1, warning viewers of a malady so mysterious that “no one knows where it comes from.”

While watching the PSA, he grew concerned: “What kind of terrible affliction is this?”

Then Black Sabbath’s lead singer Ronnie James Dio delivered the big reveal: “Help us,” he said, “put an end to autism.”

In his new book, We’re Not Broken: Changing the Autism Conversation, Garcia, the Washington bureau chief for The Independent in Britain, wrote, “I don’t think I cared about being cured of autism then; what mattered was that someone saw me. But now, I watch that ad and think about how corrosive it was to see Joe Perry and Steven Tyler of Aerosmith, whom I loved when I saw them live, say they wanted to wipe me out.”

They were, he wrote, “advocating for a cure for what made me, well, me.”

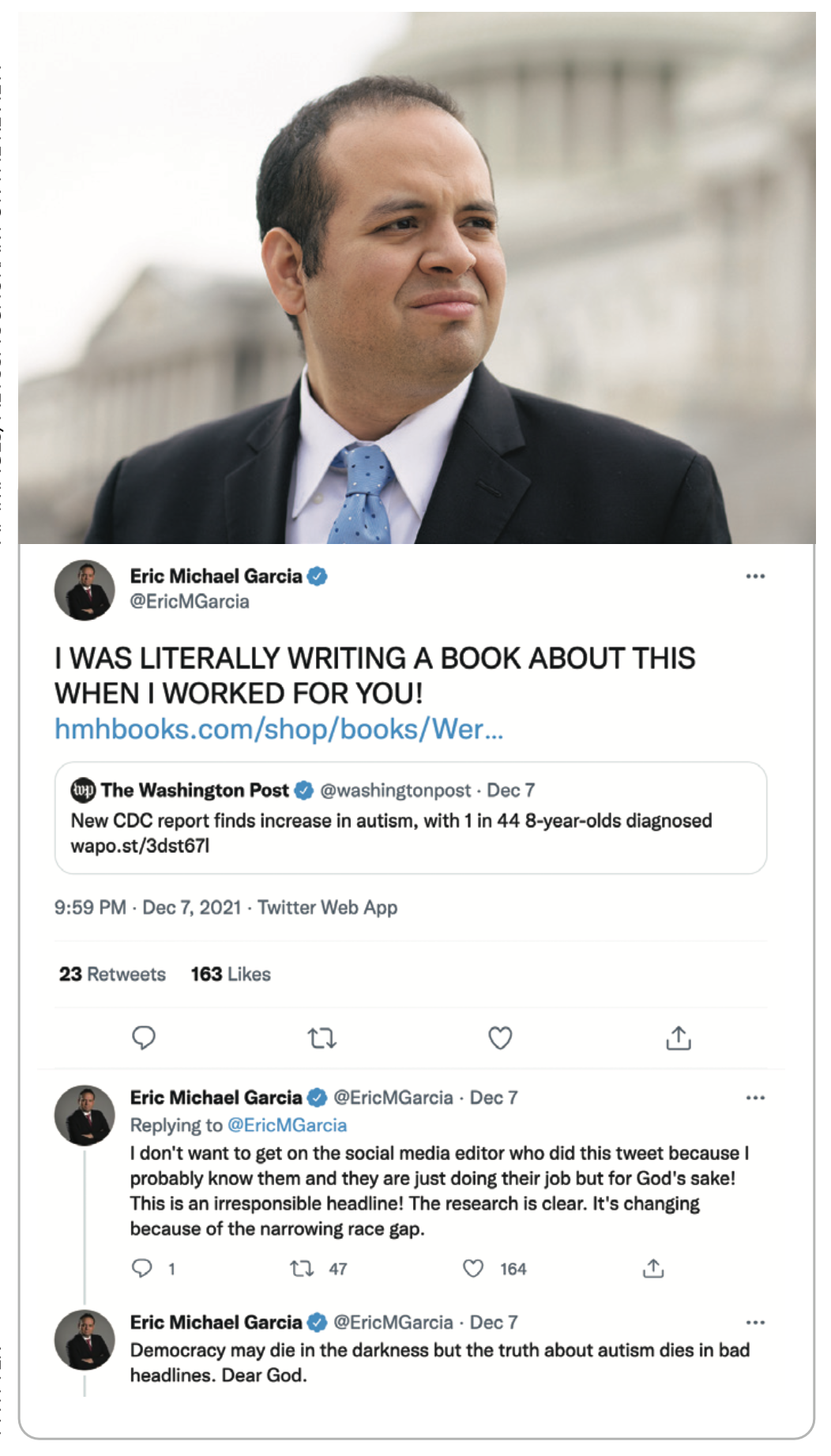

(Alyssa Schukar/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review; Twitter)

Garcia had plenty of myths to bust in We’re Not Broken, a deeply reported book for which he crisscrossed the country, talking with autistic people all along the spectrum about their careers, their educations, their living situations and their health. But perhaps none was more important than dispelling the notion that autism was an illness that needed to be fixed. It is, Garcia said, a disability that is an integral part of his identity.

“I think more about being autistic than I do being Latino or being a male,” he said. “The only times I think about being Latino is when other people remind me I’m Latino. And the only times I think about being a guy is when other people remind me about being a guy. Whereas, being autistic determines what kind of environment I live in, what kind of light bulbs I use in my place, when I take the metro to work, whether I can walk to work. It determines who I talk to, how many people I talk to, and if I’m going to talk to people today. It dictates nearly every aspect of my life.”

Garcia, 31, is a member of the Spectrum Generation — an autistic person born after the diagnostic criteria expanded to include Asperger’s (a term later retired and folded into Autism Spectrum Disorder; ASD includes a group of developmental disabilities that affect social, behavioral and communication functioning to varying degrees). He views his success through the lens of game-changing federal protections; he wasn’t interested in writing another inspirational memoir about “overcoming” autism to do great things.

“I hate those stories with a passion,” said Garcia. Even though such stories are presented as “feel-good” narratives for a broader audience, many autistic people say they constrict the boundaries of worthiness. The message: You must be nothing less than extraordinary to be accepted.

“Those stories are [told] for neurotypicals,” Garcia said, referring to people without challenges that result in a different, or neurodivergent, way of operating in the world. “They’re not for autistic people.”

Instead, he wanted to “contextualize why I was able to live the life I was able to live, and it was because of specific, deliberate policy choices.”

Garcia was born in 1990, the year the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was enacted and autism was included in the reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The laws meant he had always lived in a world where he was entitled to academic support and workplace accommodations that helped him pursue his goals.

“A lot of people, when they think about disability, they think you’re passing these laws because it’s the nice or the charitable thing to do, rather than this is a thing that gives you your legitimate rights and can change the trajectory of your life,” Garcia said. “I would not have the life I have today had the ADA and IDEA not passed.”

Garcia wasn’t interested in writing a memoir about “overcoming” autism to do great things. “I hate those stories with a passion,” he said. Even though such stories are presented as “feel-good” narratives, many autistic people say they constrict the boundaries of worthiness. The message: You must be nothing less than extraordinary to be accepted.

But even with those laws, Garcia — who has held staff reporting and editing jobs at The Washington Post, National Journal, Roll Call and The Hill — credits some of his success to good fortune. He had a mother who was a relentless advocate, professors who didn’t write him off as lazy and employers who created the working conditions in which he could thrive. He traced his luck to a personal and professional community that embraced a level playing field for the disabled so that he could succeed in a world not designed for him. It accepted him and, more important, gave him the space he needed to accept himself.

When researching We’re Not Broken, he learned those advantages weren’t available to many autistic people. “The world around them,” he wrote, “is a bigger impediment to them than their autism ever was.”

Tough questions

JohnPaul Trotter can’t recall what Debra Garcia told him about her son’s autism when they first came to his studio in Southern California. She was “pretty protective, and rightly so,” he said. Trotter said Garcia’s first guitar teacher had been a “harsh dude,” berating him for mistakes, and they were looking for someone with more patience.

Garcia was 11 and living the usual fraught preteen years while also navigating autism and Tourette syndrome, a neurodevelopmental disorder involving uncontrollable movements and vocal tics. Trotter was 18 and low-key, mature enough to hold lessons that doubled as a form of therapy. He let Garcia’s mood and experiences guide their studio time and encouraged him to participate in a garage band with other students. Garcia taught Trotter, meanwhile, the importance of being a mentor. They were a perfect match.

“He just got put in my path, and we both were the better for it,” Trotter said.

Garcia’s dad and stepdad were both musicians, and music was one of Garcia’s hyper-focused interests — one of the ways that being autistic manifested for him. When Trotter demonstrated how Muddy Waters would play a piece, Garcia would ask, “Who’s that?” Two weeks later, he’d return to Trotter’s studio and unloose a stream of biographical information about Waters that Trotter had never heard before.

(Twitter; Independent.co.uk)

“I immediately realized that he had a pretty intense passion for not only just learning the music, but also really digging into the stories about the players and the culture and learning everything he could about it,” said Trotter, who took Garcia to his first concert at the Hollywood Bowl, where backstage they talked with Guns N’ Roses lead guitarist Slash. “I’d always learn something from him.”

As the years passed, Trotter and Garcia became best friends.

When Garcia was 15, Trotter told him, “Man, you should be a music journalist. That would be cool.”

Instead, Garcia developed a love for American history and politics through reading books on the topic while growing up. Garcia said he “caught the political bug” while working on his high school newspaper. He did well enough at Chaffey College, a California community college, to make the honors program, and from there, won a White House internship when Barack Obama was president. The Los Angeles suburbs were no place for a kid who was head-over-heels about politics. Washington, D.C., felt like home.

Garcia mostly answered mail for Michelle Obama and other family members. The internship not only marked his first time living away from home; it also gave him a strong sense of his talents and a glimpse of what a political career could entail.

He decided that it wasn’t for him.

He found that he didn’t like defending the Obama administration on policy matters that he disagreed with, such as the 2011 military intervention in Libya. He realized he was using some of the same defenses that the Bush administration had used for the war with Iraq.

He discovered one skill that came naturally to him, however: challenging powerful people.

When the president’s aides took part in a Speaker Series session with the intern class, Garcia wrote, “I would research their past and try to ask probing questions. If they’d worked for Wall Street between the Clinton and Obama administrations, I asked if it affected their views on financial policy. I loved watching them be visibly uncomfortable.”

In a sense, he’d been studying politics and political journalism in various forms since he was a kid. His dad, who Garcia said is now a “rock-ribbed right-wing Republican,” first joined the party in response to Nixon ending the draft. He watched Fox News during the week but Meet the Press on Sunday.

“He told me, ‘Tim Russert is a Democrat, but you would never know he’s a Democrat,’ ” Garcia said. “That was kind of the pinnacle of what you could aspire to.”

His stepfather grew up the son of an Irish Catholic immigrant in working-class Pennsylvania; in the 1960s, that meant loyalty to Kennedy and the Democratic Party. His mom, meanwhile, shifted from the political right to the middle as she raised him. Using his deep knowledge of American politics, Garcia said he could figure out how people came to their divergent beliefs and how experiences shape people for life.

He could also reconstruct history’s molted layers to uncover clues to the present. That skill was satisfying and empowering, one that he would repeatedly employ in his future career. (A glance at his Twitter feed on any given day shows how Garcia spots patterns and dispenses insight that even the most deeply reported stories have overlooked.)

While working at the Obama White House, he won a scholarship to UNC and, in 2011, embarked in earnest on his journalism training in Chapel Hill.

He also entered one of the most challenging times of his adult life.

Blue heaven

Garcia had battled depression since the seventh grade and had seen friends come undone by its grasp. Trotter recalled the days that followed the suicide of one of Garcia’s garage bandmates, and how Garcia had led them all through their grief by playing music together. However, Garcia had moved to the other side of the country, where isolation led him to some starkly low moments.

“It really got bad,” Garcia said. “I just didn’t know anybody. I was in a new state. I just was kind of a fish out of water. That’s one of the things that people really don’t realize, is how big a problem suicidal ideation is among autistic people in college.” A study conducted in Denmark found that people with autism were more than three times more likely than the general population to attempt suicide.

Garcia said his mental health struggles, which he continues to manage, are at least partially genetic. But the compounding effects of a lifetime of navigating a neurotypical world take their toll on people with autism, he said, whether they spend their days masking their autism in an effort to fit in, being constantly misunderstood or mislabeled, enduring cruelty from peers or suffering from autism burnout — a type of exhaustion that causes shutdown and sometimes a loss of skills.

Garcia also was initially reluctant to lean on the support to which he was entitled at UNC. At Chaffey, he had developed solid study skills and made the honors program — but only after his mother pushed him to use accommodations such as quieter spaces for testing and extra time on math exams.

At Carolina, Garcia saw his autism as “something I had conquered and overcome, now that I was enrolled at a prestigious four-year university.”

Accessing services felt like cheating to Garcia, a common roadblock among neurodivergent students.

“I didn’t want people to put an asterisk next to my success,” he said.

His reluctance changed one day when he couldn’t summon answers during an exam. After the class, he nervously shared with his professor that he was autistic and had trouble sometimes in timed academic situations. Garcia expected to be accused of making excuses. Instead, the professor called Theresa Maitland at the UNC Learning Center, told her that he had a student in crisis and asked whether he could send him over.

(Twitter)

“Eric was really devastated and really stressed,” Maitland, an academic coach at the time, recalled. They began meeting weekly to discuss study strategies and “normalize” what he was going through. Many transfer students, autistic or not, struggle with the transition to UNC, she told him, where the academics are more demanding.

That a professor made the first move to help was another bit of luck. Many neurodivergent college students shoulder the burden not only of needing help, but finding, accessing and leaping over the stigma of receiving it, said Maitland. Discrimination of neurodivergent students of all ages is still a rampant and accepted practice worldwide, she said.

She encouraged Garcia to make time for hobbies such as playing guitar and for physical activity, to find a well-rounded experience where academics would not control his life. Garcia wrote that Maitland’s office was his “sanctuary and my war room,” that she became “my confidante, my adviser, and my surrogate grandparent. She never made me feel flawed or weak.”

“He was hoping autism wouldn’t be a barrier, and it was,” said Maitland, who retired in 2018 after 24 years at UNC. “But he didn’t really go through that much sorrow about it. It was like, ‘OK, this is part of me, I can’t deny it.’ ”

Accepting his autism helped Garcia find pockets on campus in which to flourish; he soon found a community at The Daily Tar Heel, where he made a tight circle of friends who, one by one, settled in D.C. after graduation and have remained close.

Another Hill to climb

Autism shows up in his work as a reporter on Capitol Hill through his ability to “have kind of a really myopic and focused interest,” said Garcia, who sorts through Federal Election Commission filings looking for patterns when he’s bored. “And then, just the ability to absorb information. Once something sticks, it sticks there forever.”

There have been challenges, he said, but understanding employers have helped lessen them. When he worked in bustling newsrooms, he wore noise-canceling headphones to combat sensory difficulties. He also had a point person who signaled Garcia during editorial meetings if he was rambling and helped him focus his ideas each week.

“The other thing is that sometimes I’ll get myself in trouble,” he said. “I followed a senator into the men’s room to ask a question, and I didn’t realize that was a bad thing to do. And then somebody told me, ‘Look, if you do that again, you’re gonna lose your Capitol press pass.’ I was like, ‘OK, I’m sorry, I’m not gonna do that again.’ ”

But misreading social cues also can have its benefits, Garcia has learned.

“Because social norms are a second language to me,” he said, “sometimes I can see when social niceties are being used as a cover for the truth or when somebody is giving me a non-answer.”

Instead of dropping the question, he pursues it from another angle until he gets a response.

“It’s definitely a different way of operating,” he said. “I don’t think it makes me better or worse at my job as much as it just makes things different.”

His divergence, especially from stubborn stereotypes about people with autism, was part of what led Garcia to write an essay on autism for the National Journal in 2015 that became the basis for We’re Not Broken. As an autistic man working in a non-STEM, empathy-driven field — a quality society often wrongly assumes autistic people lack — he recognized how little neurotypicals grasped autism’s diversity.

Autism shows up in his work as a reporter on Capitol Hill through his ability to “have kind of a really myopic and focused interest,” said Garcia, who sorts through Federal Election Commission filings looking for patterns when he’s bored.

“The fact that I came from a very misunderstood class of people maybe helps me be more empathetic to people who are also misunderstood,” said Garcia, who wrote in his essay about being handcuffed by schoolyard bullies in sixth grade. “Whether they’re disabled people, transgender people or whether they’re people from immigrant communities or any other group of people. I’m like, ‘Why do we misunderstand them? What does that say? And what does that misunderstanding say about us?’ And usually, our misunderstanding is saying a lot more about us than it does about that group.”

During the three years he researched the book, Garcia found that even he had internalized myths about the autistic community.

“I found out that there were non-speaking autistic people who were capable of going to college or who were capable of working, and they just needed the right support,” Garcia said. Meanwhile, he discovered verbal autistic people who had been diagnosed late in life and wound up dropping out of college because they did not realize they needed disability support.

It’s why the terms high-functioning and low-functioning are meaningless and potentially harmful to the autistic community, he said.

“If you look at someone like myself and say, ‘Oh, well they’re high-functioning, so they must be able to go to college,’ you ignore the legitimate support needs they have.” Meanwhile, terming an autistic person as low-functioning assumes low expectations.

The central myth he busted for himself goes right to the heart of those messages he absorbed from celebrities and media growing up. He discovered that using person-centered language for autistic people, rather than identity-first language — saying a “person with autism” instead of “autistic person” — perpetuates the idea that autism is a disease.

Garcia knows that using identity-first language is counterintuitive for many people.

“A lot of good liberals say that,” he said. “But a lot of autistic people would say, ‘We need you to see this as an inextricable part of who we are.’ ”

Although the book has earned Garcia significant accolades and attention since it debuted in August, the only pat on the back he has given himself is a new Les Paul guitar. He isn’t considering switching to autism advocacy, preferring instead to “write about these communities and tell their stories more and include their voices in media. That is what my role is.

“Working on this was as much a learning process for me as [reading] it is for anybody else,” Garcia said. “Nowadays, when people try to call me as an expert about autism, my response is: ‘I’m learning as much as you guys are.’ ”

Beth McNichol ’95, a freelance writer based in Raleigh, is a former associate editor of the Review.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.