Holding Onto Herself

Posted on Sept. 12, 2019

Sanni McCandless ’14 co-founded Outwild, using climbing, yoga, workshops and life coaching to help “people who feel a little bit trapped. People are looking for ways to strip away that surface we live on, where our phones are in our hands all the time.” (Photo by Martina Zando)

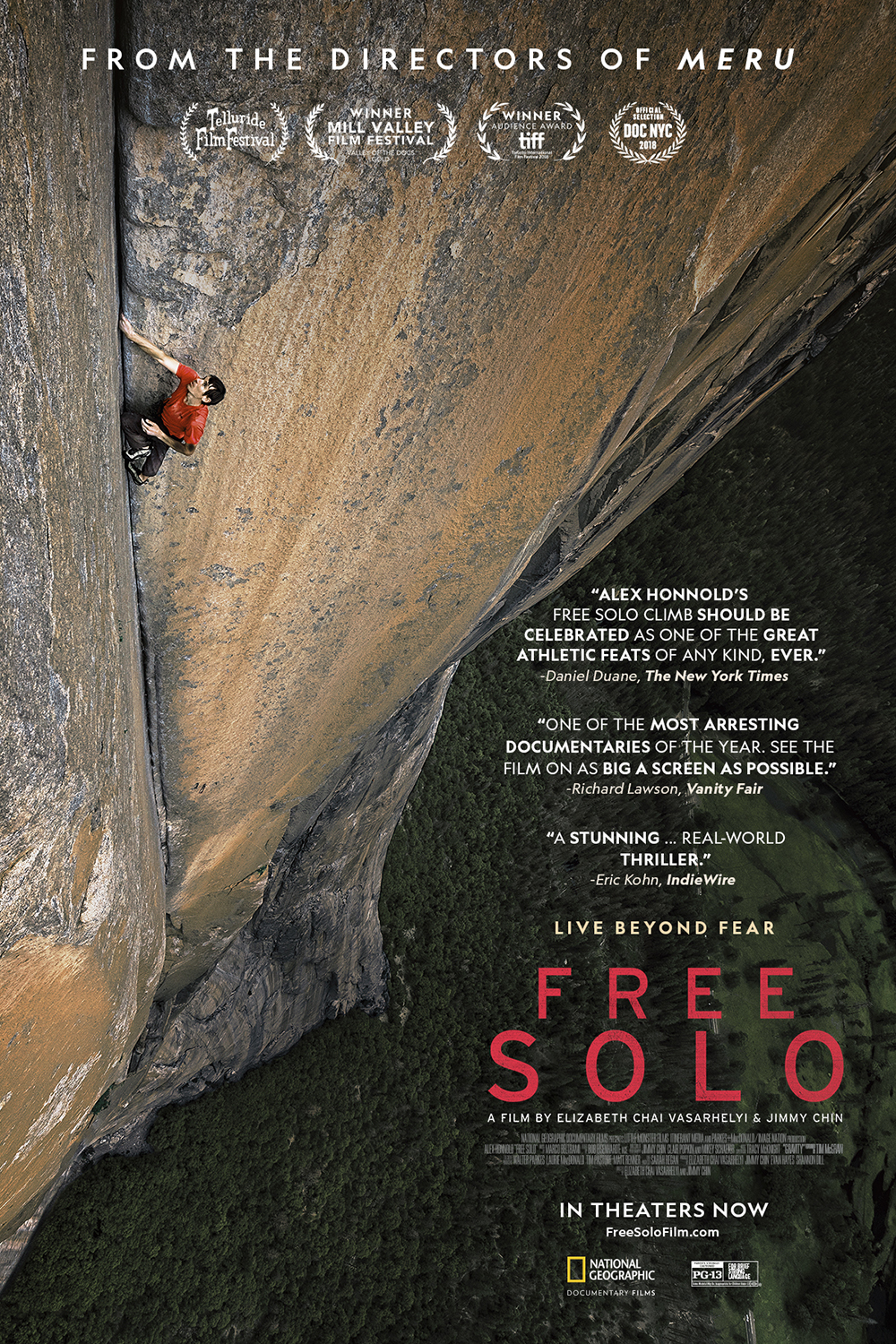

With El Capitan’s 3,200-foot-high granite rockface looming behind her, Sanni McCandless ’14 pulls her car over and lets her mind go to a dark place.

For the first time in the almost two years since she began dating Alex Honnold, the most accomplished free solo climber in the world, she allows herself to think about all the things that could go wrong on El Capitan the next day — when Honnold would attempt to become the first person to climb Yosemite’s monolith with no ropes or safety gear.

“Why do you want to do this?” McCandless wonders through tears. “It’s a totally crazy goal.”

McCandless said the Free Solo experience with climber Alex Honnold showed her that “I have to be so strong in myself, because otherwise I would just get swept up in that tsunami…”

This scene in Free Solo, the 2019 Oscar-winning documentary that immortalizes what The New York Times called “one of the greatest athletic feats of any kind, ever,” shows one of the film’s most relatable themes: What can you hold onto for someone else without losing yourself?

In the film, the question plays out not just for McCandless, who struggles to support a dream that could end her partner’s life, but also for Honnold, who must confront the long-held notion that his sport’s high stakes leave no room for emotional attachments on the ground.

What the film’s soaring cinematography and white-knuckle tension don’t show is how McCandless — whose biggest fear after leaving UNC was that she “would learn to be independent and somehow lose that independence” — preserved her own identity after meeting Honnold and his singular personality in November 2015.

She was working in marketing for a Seattle energy startup and had just started climbing for fun. He lived out of a van and was the center of climbing’s most dangerous universe, a literal rock star.

While McCandless could see her life and career taking many different paths, Honnold had his eye on only one.

“Alex’s life has the forward momentum of a tsunami,” said McCandless, who lived part time in his van and trained with Honnold for two years. “He knows exactly what he wants — and especially leading up to [climbing El Capitan]. There was just this clarity and drive and motivation, just hurtling him in one direction. I have to be so strong in myself, because otherwise I would just get swept up in that tsunami and lose sight of my own passions and joys.”

Climbing was — and still is — just a hobby for her, a way to feel strong and be outdoors. But the more time she spent in the sport’s community, the more its lessons became a roadmap to life outside a marketing cubicle.

“It changed all the barriers I had in my head about what a job could look like,” she said. “I met people who would work really hard four months out of the year and then go on climbing trips. I saw all these different ways to do life. There was no strict template.”

“People walk away from the film and think they know you,” said McCandless, who now shares a van and a home with Honnold, in Las Vegas. “It took me a while to be OK with that. No matter who you are, you have to constantly try to tap into what you care about and tune out everyone else’s opinions about your life. For me, that was definitely the biggest lesson of the whole film.”

As Honnold prepared to take on El Capitan in 2017, McCandless revisited a dream from her days at UNC, where she was a psychology major: She became a certified life coach, intent on helping others erase templates and define their own goals.

“I really wanted to help people focus forward,” she said. “We have specialists to help us in all areas — diet, exercise, health — except for our actual lives. We rarely ask ourselves what we’re most passionate about, what really fulfills us. Coaching is all about giving people a foundation for seeing themselves differently and holding them accountable.”

McCandless also saw the clarity that time outdoors inspired. With friends, she launched Outwild last fall, a three-day festival retreat with climbing, yoga, workshops and life coaching that attracted about 100 participants, ranging from age 20 to 60. The organization held a women’s retreat in June in New Hampshire and planned a second festival in California this fall.

Outwild is “for people who feel a little bit trapped,” said McCandless, who spent her early childhood in Washington state before moving to Chapel Hill. “People are looking for ways to strip away that surface we live on, where our phones are in our hands all the time. It’s not about uprooting your life to live in a van, but it is about finding subtle changes that you can incorporate into your everyday life to feel more connected to the outdoors or to your values.”

As Outwild debuted last fall, McCandless also was navigating Free Solo’s theatrical release. Watching the details of her life and Honnold’s climb on screen was both surreal and excruciating; she cried in all the same places she did when she was living it. And when social media weighed in with advice, criticism and commentary — about the couple’s climbing safety, about the ethics of soloing, about the perils of relationships in the sport — the experience became a familiar test:

What do you hold onto without losing yourself?

“People walk away from the film and think they know you,” said McCandless, who now shares a van and a home with Honnold, in Las Vegas. “It took me a while to be OK with that. No matter who you are, you have to constantly try to tap into what you care about and tune out everyone else’s opinions about your life. For me, that was definitely the biggest lesson of the whole film.”

— Beth McNichol ’95

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.