House Sweet it Is

James Taylor’s boyhood home has a new lease on life and is filled with art thanks to J.K. Brown ’84 and Eric Diefenbach.

By Janine Latus

“Even the old folks never knew

Why they call it like they do

I was wondering since the age of two

Down on Copperline”

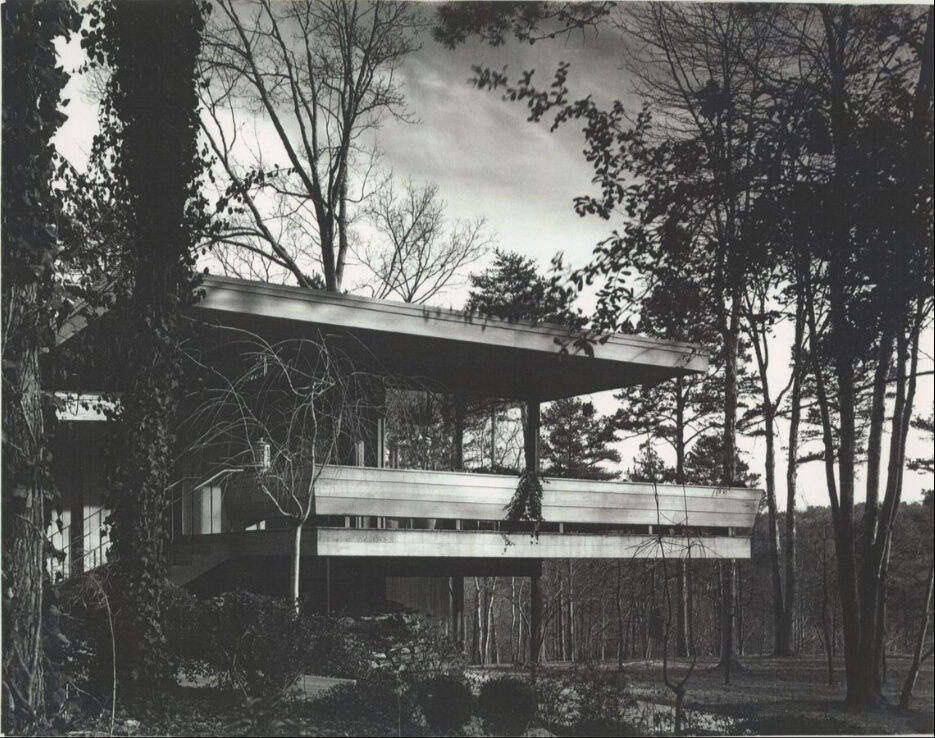

Eric Diefenbach and James Keith “J.K.” Brown ’84 saw the house’s potential. The couple hired the Raleigh architecture firm in situ studio to create a design to serve as their home and a place to display a rotating selection of their art. Photo: Kate Thompson.

Songwriter James Taylor’s Chapel Hill childhood home had fallen into disrepair. It sat on two dozen arboreal acres in the Morgan Creek neighborhood, just south of Fordham Boulevard. Taylor, whose song “Carolina in My Mind” is practically an anthem at Carolina, as a boy tromped with his dog, Hercules, through the surrounding woods, his days freewheeling and unsupervised, on endless adventures later memorialized in his 1991 song “Copperline.”

“Half a mile down to Morgan Creek

Leaning heavy on the end of the week

Hercules and a hog-nosed snake

Down on Copperline”

The song, co-written with novelist and playwright Reynolds Price, talks of his first kiss, watching his daddy dance (moving like a man in a trance) and of the moonshine he and his friends tried to make in a homemade still, but also of his recognition that the woods and wild freedom were forever gone.

“I tried to go back, as if I could

All spec house and plywood

Tore up and tore up good

Down on Copperline”

In 1974, after Taylor’s mother and father divorced, the Taylors sold the 3,172-square-foot home and relocated, most of them to Massachusetts. It would be more than 30 years before it was on the market again, when it sold for $1.66 million at auction to New York-based art collectors James Keith “J.K.” Brown ’84 and Eric Diefenbach. They bought the house because it was a beautiful home and it allowed them to be closer to family. The partners spent five years and an additional $2 million nearly gutting the entire house and remodeling it into a place worthy of showcasing their art collection, which includes an international array of abstract artists whose works are contemporary to the home.

“We’d been looking all over the country for an interesting midcentury modern house to restore,” Diefenbach said, “and this one was in Chapel Hill, near J.K.’s hometown, right by the University, on nearly 25 acres, and had a bizarre and interesting provenance. Plus, we believe in reusing rather than destroying.”

Until then, the future of the house was in doubt. After the Taylors sold their home, the property became so neglected that neighbors feared it would be sold to a developer and its land would become littered with McMansions. However, zoning laws wouldn’t allow such development because the property’s short street frontage limited what could be built on the lot.

After 30-some years, the second owners died and their heirs put the house on the market in 2016. A for-sale sign beckoned potential buyers, and inquisitive Taylor fans occasionally stopped by to peer through the house’s windows. The preservation group USModernist, which bills itself as the “largest open digital archive of midcentury modernist houses in the world,” helped host open houses, selling tickets to more than 1,300 people who each had half an hour to tour the home, either drawn to its iconic architecture or — likely the majority of them — curious looky-loos or fans paying homage to its former famous occupant.

“I’d turn around and there’d be some middle-aged guy on the porch, strumming a guitar and singing ‘Sweet Baby James’ to no one in particular,” said USModernist founder and CEO George Smart ’83, referencing one of Taylor’s hit songs. “It was hilarious.”

Smart, whose nonprofit organization has documented 5,000 modernist homes in North Carolina, said the home’s condition was a five on a scale of one to 10. Water was seeping in through the roof, yet the house had great bones and thick beams. “So it was not in the range where you would even consider tearing it down,” he said.

Behind the house was an architecturally incongruent cottage, where James, the second-oldest of five Taylor children, and his older brother, Alex, lived as teenagers. The cottage’s rail, with James’ initials carved into it, was saved and is stored in a playhouse on the property.

From rundown to showcase

After the Taylors sold their home, the property became so neglected that neighbors feared it would be sold to a developer and its land would become littered with McMansions. After the second owners died, their heirs put the house on the market in 2016. A for-sale sign beckoned potential buyers, and inquisitive Taylor fans occasionally stopped by to peer through the house’s windows.

The house had been the pride of Taylor’s mother, Trudy. She’d worked with the famed modernist architect George Matsumoto, who was teaching at what was then called N.C. State University’s School of Design, the hotbed of the modernist movement at the time. Their visions didn’t align, though, and three-quarters of the way through the project they had such a personality clash that Matsumoto ostensibly (and temporarily) swore off residential design, “not wanting to work with the wives,” according to the USModernist website. (One wonders whether Trudy was difficult or was it that at the time women were labeled “difficult” for stating an opinion.)

The Taylors hired another renowned modernist architect, John Latimer, to complete the design. But much of the house is classic Matsumoto: a flat roof, an unobstructed internal view from one end of the house to the other, natural woodwork, mahogany cabinetry and large windows and sliding glass doors in the rear. Each of the five Taylor children had ground-floor bedrooms that opened to the outside, allowing them to exit the house without checking in with their parents.

“I don’t think I would have become a songwriter if I hadn’t had all those free days to let my imagination roam,” Taylor later said in his audiobook Break Shot: My First 21 Years, an intimate story about his upbringing in a dysfunctional family, his treatment in a psychiatric hospital, his battle with depression and heroin addiction. Taylor was on tour in Europe and unavailable for an interview, according to his agent.

David Perlmutt ’75, a childhood friend of Taylor’s, remembers the freedom they had growing up. “We were all on a long leash,” he said in an interview. “Before we could drive, we’d take off on our bicycles at sunrise and weren’t expected home until dinner, with no questions asked.”

Across from the bedrooms was a communal shower, with two shower heads and a drainage pipe that dripped tar when the roof was resurfaced. “Our parents would throw all five of us in there and often the next-door neighbor kids, a cup of Tide, a cup of bleach and a rubber mat we’d put over the drain,” one of Taylor’s younger brothers, Hugh Taylor, said in an interview. “Then they’d put 8-to-10 inches of water in there, and we’d splash around until we were clean.”

As the kids got older, Trudy had a two-bedroom cottage built for James and Alex, its Swiss chalet-like architecture at odds with the main house. It had a makeshift shower made from corrugated metal sheets, like those found at summer camps, two bedrooms and a hang-out room with a piano, where the boys practiced with their various bands. The kids carved their initials into the railing of what neighborhood children called the Boys’ House, said Perlmutt, who lived just across the private lane.

The home’s electrical system was outdated knob and tube, a maze of insulated wire and porcelain tubes; the plumbing and heating were obsolete. Yet Brown and Diefenbach saw the house’s potential. Besides, Brown, senior managing director at the New York investment firm Coatue Management LLC, had grown up about 30 miles away in Siler City, where his mother still lives, and, 16 of their 29 nieces and nephews (ages 2 to 46) live nearby, so he thought the home could become a family gathering place.

The couple hired the Raleigh architecture firm In Situ Studio to create a design to serve as their home and a place to display a rotating selection of their art. A contractor performed a selective demolition, salvaging some of the original 2 1/4-inch pine flooring and taking nearly everything else down to the studs. “You could see right through the house,” said Matt Griffith, an architect with the firm.

The biggest challenge was modernizing the interior to match Matsumoto’s original vision. In Situ had found some of the original plans but not a complete set. The architecturally clashing guest house had to go, and the east end, which Griffith said “was cut off with a really flat, weird concrete block wall with a greenhouse against it,” needed a redesign.

“The house was almost a masterpiece, but never quite finished the right way,” Griffith said. “It was almost like a mishmash of stuff, all of which was pretty good, but it didn’t work well together.”

They designed a new guest house that mimicked the main house’s lines and added a pool and pool house with an outdoor family room with a big-screen TV, which the owners use to encourage their nieces and nephews to visit. A portion of the main house’s all-glass south wall overlooking the lawn was replaced with solid walls, both for privacy and to hang paintings.

The result is itself a piece of art. “Modernist houses look different, and they live different from traditional houses,” Smart said. “They’re sculpture you can live in.”

The house had been the pride of Taylor’s mother, Trudy. She’d worked with the famed modernist architect George Matsumoto, who was teaching at what was then called N.C. State University’s School of Design. Three-quarters of the way through the project they had such a personality clash that Matsumoto ostensibly (and temporarily) swore off residential design.

Part house, part art exhibit

Brown and Diefenbach began collecting art early in their 35 years together, in part as mementos from their travels. They were in Eastern Europe in the late ’80s, around the time the Berlin Wall came down, and were introduced to contemporary works, including by German photographer Thomas Struth, Icelandic-Danish sculptor Olafur Eliasson and Dutch photographer Rineke Dijkstra, among others. Trips to Vietnam, Japan and other parts of Asia introduced them to more artists, expanding their collection into paintings by Japanese abstract artist Yayoi Kusama; hard-edge abstractionists John McLaughlin and Karl Benjamin; and the late Chinese American contemporary artist Matthew Wong.

Brown is deeply involved with Carolina. He serves on the Chancellor’s Philanthropic Council and the board overseeing the UNC Investment Fund and is board chair of Arts Everywhere, which works to incorporate arts throughout campus. Among their projects are a basketball court on the south campus painted by African American contemporary artist Nina Chanel Abney and the annual spring celebration Arts Everywhere Day, which includes pianos placed strategically across campus, pop-up opera and spoken-word performances.

Diefenbach and Brown plan to open their home occasionally to university and museum groups eager to see the art — and perhaps the famous house.

In 2015, ARTNews magazine ranked the couple among the top 200 art collectors in the country. They speak of each piece with fondness and familiarity, bantering about the artists and their influences and how one piece plays off another. They loan their art widely: The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut, where Diefenbach is past chair and serves on the board; The Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University, which hosted an entire show of their German art; The New Museum of Contemporary Art in Manhattan, where Brown has served as chair; the Guggenheim and both The Museum of Modern Art and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; and, locally, the Ackland Art Museum, where Brown served as chair for 10 years and which has hosted two shows of the couple’s collection.

During the pandemic, Ackland featured Yayoi Kusama: Open the Shape Called Love, with much of the exhibit online to reach the widest audience. “We want our collection to be seen,” Diefenbach said, “both in terms of inviting groups into our homes and lending.”

“Particularly the young artists,” Brown adds. “It’s our responsibility to make sure their work is seen.”

Just inside the living room is a three-dimensional multimedia piece that resembles a corset, by the artist Harmony Hammond, who had her first serious solo retrospective at the Aldrich when she was in her 80s. “We like to give shows to under-appreciated artists,” Diefenbach said. “Women artists of that generation were too often overlooked.”

Hammond’s piece hangs across from a painting of what is surely a mental health hospital by outsider artist David Byrd, who worked for 30 years as an orderly in a psychiatric ward in New York. The colors and perspective are flat, the building isolated and institutional. The two pieces are — in art circle parlance — in conversation with each other. “The mental hospital is across from a feminist work about feeling trapped in a kind of corset,” Brown said. “They’re both dealing with human conditions.”

On another wall is one of the seven Kusamas on the property, this one from her Infinity Nets collection. The art is mostly contemporary to the house, the furniture chosen to complement it and the architectural era. Even the rugs are by renowned creators.

Brown and Diefenbach began collecting art early in their 35 years together, in part as mementos from their travels. They speak of each piece with fondness and familiarity, bantering about the artists and their influences and how one piece plays off another. They loan their art widely.

The house is Brown and Diefenbach’s fourth home. They have a top-floor flat in a former dry goods warehouse on Manhattan’s Upper West side, with a view down 72nd Street to Central Park and up Columbus Avenue to the Museum of Natural History. Another of their homes perches on a hilltop on about a dozen acres overlooking the horse farms around Ridgefield. (“It’s basically four glass boxes stuck together,” Brown said.) They also rent a cottage that’s a converted 1920s motel in East Hampton, among the dunes, on Long Island.

Diefenbach, who graduated from Columbia University, is a litigator who now spends much of his time arranging loans, transport and insurance for their art collection, and rotating pieces among their homes, both to keep them visually fresh and to offer a respite from exposure to sunlight and the environment. Brown gives him full credit for curating the art and building dialogues between the pieces, aesthetically and conceptually grouping works by different artists to create some sort of message or to pose a question. “I try, but it’s a process and never works the first time,” Diefenbach said. “You plan something, and when you hang it, it just isn’t right.”

Much of the Chapel Hill home design was done remotely due to the pandemic, and there are still things to tweak, like the spotlights that offset some of the natural light.

There is certainly art everywhere in their home. Windowless bathrooms provide protected space for photographs that shouldn’t be exposed to daylight. A colorful Eliasson mirror is tucked into a walk-in closet. The couple were fans and later friends with Eliasson before his famed 2008 display of waterfalls throughout New York City. Diefenbach and Brown have thousands of works distributed among their homes, climate-controlled storage units and museums — and stories to go with most of them. They plan to open their home occasionally to university and museum groups eager to see the art — and perhaps the famous house, a Matsumoto-Latimer combination, lovingly restored to a lovely abode to showcase a new generation of artists.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.