In the Room

Rep. G.K. Butterfield Jr.’s archives document North Carolina’s complicated political and racial history — and his role in it.

by Elizabeth Leland ’76

Facing one of the toughest decisions of his political career last year, U.S. Rep. G.K. Butterfield Jr. thought back to what happened to his father during the Jim Crow era.

Butterfield was 10, vacationing in New York City with his family in 1957, when his father, George Kenneth Butterfield Sr., flew home to Wilson for an emergency city council meeting. A prominent dentist, Butterfield Sr. was the first African American to serve on the council and was up for reelection.

At the meeting, members approved a change in how candidates ran, from representing districts to running at-large. The switch guaranteed Butterfield Sr.’s defeat by forcing him to run citywide rather than in his majority Black district.

Nearly 65 years later, Butterfield found himself in a similar predicament.

Congressional maps adopted by the N.C. state legislature last fall diluted the strength of Black votes in Butterfield’s district, making it less likely he could win reelection in November for a seat he handily won in nine previous elections. Butterfield announced he would retire when his term ends in January 2023.

Though Butterfield is an avid student of history — he recently donated his extensive collection of historical materials to Carolina’s Wilson Library — he said he never saw the redistricting changes coming.

“We are going backwards now,” he said. “We’re continuing to see legislation that marginalizes African American communities. We saw it in 1900 [when North Carolina adopted rules that effectively disenfranchised most Black voters], and we saw it in 1957, and now we’re seeing it again.”

Butterfield filed copies of speeches, campaign buttons, newspaper stories and other documents about pivotal historical moments. He saved materials about diplomatic trips abroad, congressional meetings and the newly redrawn congressional maps.

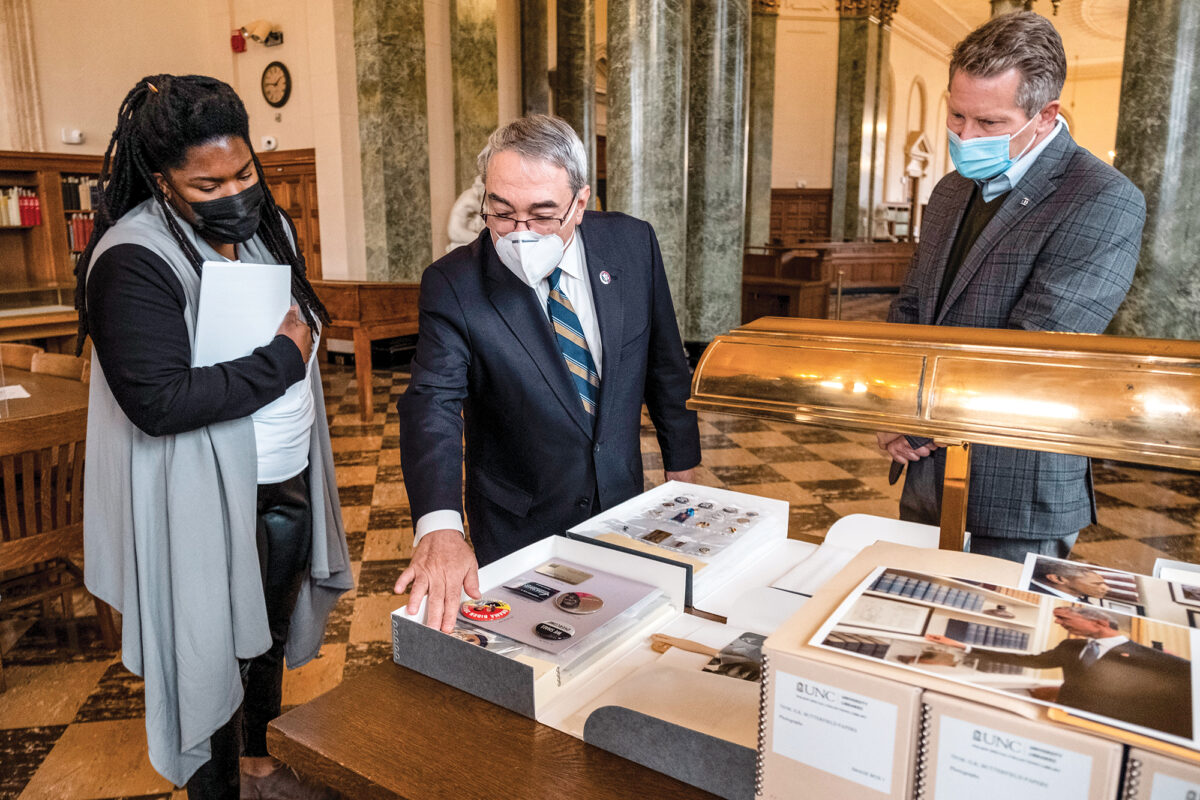

G.K. Butterfield looks at a 30th reunion photo of the Charles H. Darden High School class of ’65 and a black-and-white shot of his high school band’s 1964 trip to the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. Butterfield donated his archive to Wilson Library’s Southern Historical Collection. Photo: UNC/Jon Gardiner ’98

Amateur historian

A former chair of the Congressional Black Caucus, Butterfield is known as an outspoken voice on voting rights and other issues affecting African Americans. Less known is his role as amateur historian. Over 50 years, Butterfield collected materials documenting North Carolina’s complicated political and racial history — and his role in it.

He filed copies of speeches, campaign buttons, newspaper stories and other documents about pivotal historical moments, including when he accompanied President Barack Obama to Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015 for a memorial service held for nine African Americans killed at Mother Emanuel AME Church by a white supremacist. He saved materials about diplomatic trips abroad, congressional meetings and the newly redrawn congressional maps.

As one of seven people of color to represent North Carolina in Congress since Reconstruction, Butterfield said his archives contain “nuggets of history” that may be important. Now 75, he decided it was time to find a permanent place in North Carolina to preserve the collection. He chose the Wilson Special Collections Library because of its Southern Historical Collection and its ability to digitize materials.

Butterfield’s papers join those of dozens of other North Carolina-born politicians, including former Chapel Hill Mayor Howard Lee ’66 (MSW), former Gov. Terry Sanford ’39 (’46 LLBJD) and former U.S. Rep. Mel Watt ’67.

Chaitra Powell, curator of the collection, said the 20 boxes of material Butterflied donated add an important perspective to the library’s archives — that of an African American politician who devoted his career to fight for civil rights.

“It’s not just his legislative papers or his bills or policies,” Powell said. “It’s the story of what made him. It’s the story of Wilson, North Carolina, and of his parents and all these inspirations that took him into public service. Everything he documents is history-making, whether it’s the presidency of Barack Obama or his friendship with [the late Congressman] John Lewis. He was there in the room for these important moments of history.”

29,000 photos, 800 funerals

“It’s not just his legislative papers or his bills or policies,” said Chaitra Powell, left, curator of the Southern Historical Collection. “It’s the story of what made him. … Everything he documents is history-making, whether it’s the presidency of Barack Obama or his friendship with [the late Congressman] John Lewis. He was there in the room for these important moments of history.” Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz is on the right. Photo: UNC/Jon Gardiner ’98

He doesn’t remember many details about the election in 1957, but he said he will never forget his father’s disappointment. “My daddy was a diplomatic-type person, and I have taken on his personality,” Butterfied said. “It would take a lot for my dad to get worked up, but he was clearly disappointed.”

As an undergraduate at N.C. Central University in Durham in the 1960s, Butterfield channeled his energy into voter registration drives. In law school at NCCU, he studied how best to use the law to protect the rights of underserved communities. He represented mostly low-income people as a civil-rights attorney in private practice in Wilson for 14 years. He then served 15 years as a judge on both the N.C. Superior Court and the N.C. Supreme Court before being elected to Congress in 2004.

All the while, he amassed his archives, ranging from African American history in Wilson to African American history in the United States. When he accompanied Obama on trips or attended events at the White House — including a preview of the movie Selma with the cast and TV personalities Oprah Winfrey and Gayle King — he stored materials from those occasions in what he called “an Obama box.”

Since being in Congress, Butterfield said he has taken about 29,000 photos, documenting events of the past 18 years with a bulky Canon EOS 40D camera and more recently with his iPhone 12. He also collected programs from 800 funerals, including those of Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela and Colin Powell.

“I’m an amateur researcher,” he said. “I’m not a professional.”

Butterfield expressed disappointment at the redistricting vote that led to his retirement. Although a revised map drawn by a nonpartisan panel of experts restored a solid Democratic majority to his district, he is sticking by his decision to retire Jan. 3. He is undecided about what he will do next. But he said he is certain of two things: He will continue to advocate for voting rights, and he will continue gathering documents to add to his collection at Wilson Library.

A better understanding of the past, he said, can help guide us in the future.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.