The Nation's Toolbox

As the venerable Wilson Library closes for yearslong renovations,

researchers and students brace for a pause in archive access.

by Ira Wilder

This article was updated April 4, 2024.

When Maggie Fritz-Morkin, an assistant professor of Italian, read that most of Wilson Library’s special collections were to be inaccessible for nearly three years, she was in disbelief.

“I blinked, and I said, ‘Surely not,’ ” Fritz-Morkin recalled. “And then I looked again the next day — yes, indeed.”

When Maggie Fritz-Morkin read that most of Wilson Library’s special collections were to be inaccessible for nearly three years, she was in disbelief. (Photo: Carolina Alumni/Ira Wilder)

She is one of thousands of researchers and instructors who rely on the special collections to advance their field and immerse students in tangible bits of history. Antwain Hunter, an assistant professor of history, is another. “I’m going to spend the spring and the summer trying to basically cram — research, research, research,” Hunter said.

Wilson Library is a collector of history, a preserver of history and a piece of history itself. But the nearly century-old building is in need of some serious renovations. The entire library will close early next year for refurbishments that are more concerned with safety updates than cosmetic appearances. It will remain closed through 2027. But as early as August, its expansive special collections will become inaccessible, with staff beginning the process of moving materials out of the library, complicating research and classes. (Digital special collections, online research and instructional expertise will still be available.) It’s a necessary step to protect its collections and the landmark building from the disruption and dust that heavy equipment will cause. During the closure, students and researchers will lose access to a bastion of scholarship that both manifests the University’s research mission and harbors millions of invaluable historical pieces.

The library will celebrate its centennial in 2029, but University Librarian María Estorino is already thinking beyond that. “We have been responsible for that building and its collections, whatever they may have been at any given time, for almost 100 years, and the next 100 years will be made possible by this project,” she said.

Building boom

Nearly everything Carolina knows about itself is stored in Wilson Library, including materials related to the building’s construction and opening. (Photo: Carolina Alumni/Ira Wilder)

Joe Hewitt ’60 (’66 MSLS), who served as university librarian from 1993 to 2004, wrote in a history of the library that it was in Wilson where he “began to realize the difference between the University and high school, and between the cozy but restricted world of my hometown and the vast world of the mind as embodied in a great research university.”

This was certainly the aim of the library’s benefactors. Before 1920, the University was a small, provincial college that mostly taught the classics to an almost all-male student body, said University Archivist Nicholas Graham ’98 (MSLS). Wilson Library, completed in 1929, was part of a campus building boom that transformed the University. More than 16 structures, including Kenan Stadium and The Carolina Inn, were constructed between 1920 and 1929. With the building expansion, UNC established itself as a modern research university, offering graduate programs and specialized education.

“University leaders recognized that in order to have a major research university, you needed a library that could support the research that was happening all over campus,” Graham said.

Louis Round Wilson (class of 1899) was the university librarian from 1901 to 1932. He wanted the library to reflect the importance the University placed on research and to impress students, whether by inspiration or intimidation by the building’s grandeur, according to Hewitt’s history of the library. The library, now formally known as the Louis Round Wilson Library, was named for him in 1956 and is one of the only buildings on campus named for someone who worked in a building rather than named for a benefactor.

Since it was opened, Wilson Library has stood as the tangible manifestation of the University’s research mission. Today, the collection has caught up to the grandeur of its building.

Wilson Library’s special collections are organized into five units: the North Carolina Collection, the Rare Book Collection, the Southern Folklife Collection, the Southern Historical Collection and the University Archives and Records Management Services. Together the collections offer millions of books, manuscripts, recordings, photos, artifacts and works of art.

Some material is sought out by the library; some is procured at auction; and other items are donated by third parties or transferred to the library from the University.

Steven Weiss, the curator of the Southern Folklife Collection, sometimes makes home visits to evaluate potential acquisitions. He recalled the home visit that allowed the library to acquire the Ray Alden Collection. Alden, a folk musician and record producer who lived in New York until his death in 2009, was a collector of old-time music who founded the Field Recorders’ Collective, preserving and producing unique traditional Appalachian music. Alden’s wife, Diana, provided Weiss with context for each piece that might have been impossible without a home visit. “It also gives us the chance to actually meet, because these folks are really turning over their legacies to us,” Weiss said.

Wilson Library houses all the University’s special collections, which are organized into five units: the North Carolina Collection, the Rare Book Collection, the Southern Folklife Collection, the Southern Historical Collection and the University Archives and Records Management Services.

The many pieces that arrive at Wilson are cataloged by the Special Collections Technical Services department, which is a bridge between acquisitions and references, said Jackie Dean ’96 (’98 MSLS), the head of archival processing. Dean and her colleagues create the searchable descriptions for incoming materials. “We analyze the materials, see what their context is and try to communicate as much of that as we can to researchers,” Dean said. “Since, of course, you can’t just walk around our stacks and pick out what you want to see.”

One of Maggie Fitz-Morkin’s graduate students encounters an early work by Giovanni Boccaccio, a part of Wilson Library’s Rare Book Collection. (Photo: Carolina Alumni/Ira Wilder)

Archival materials survive only through preservation. For example, even if kept in an extremely cold environment and overseen to the best of conservators’ ability, audiovisual recordings often deteriorate quickly, much faster than paper documents. So the library is racing to digitize its audio tapes. “A cassette tape that your mother made in 1982 might be unlistenable today,” said Elizabeth Ott, interim director of Wilson Library. “There’s an urgency around a lot of audiovisual resources.”

Audiovisual preservationists and student assistants reformat the materials, which include everything from niche oral histories, such as elders’ recollections of a rural African Methodist Episcopal church near Hillsborough, to the audiovisual recordings Ken Burns used to produce his blockbuster documentaries on the Civil War, country music and baseball.

Digital transformation

Wilson is also digitizing books, which allows library researchers to make previously hard-to-find information more accessible. For example, a project called On the Books, which digitizes copies of the state’s civil code books from the North Carolina Collection, has made the text keyword-searchable. The library’s goal is to use that to identify Jim Crow laws, which can lead to a better understanding of the laws by allowing researchers to mine text and use machine learning. The project has received funding from the Mellon Foundation and is digitizing segregation laws of other states. “We’re really thinking about preservation activities in a much broader scope,” Ott said. “How can we make things more usable? How can we transform them? How can we transform how people are able to use them?”

The N.C. Digital Heritage Center, housed in the library’s lower level, works with counties across the state to preserve local materials, especially newspapers. The materials are digitized, made publicly available and delivered back to counties. The program, which provides richer and deeper histories of the counties, is conducted in partnership with the State Library of North Carolina.

Telling stories is also a mission of the University Archives. Nearly everything Carolina knows about itself is stored in Wilson Library. Materials in the archives date back earlier than the University’s 1789 founding. The oldest materials in the University Archive are land grants, deeds and financial records that document the University’s conception. Researchers (or the just curious) can find the correspondence of chancellors, presidents, provosts and deans, minutes from faculty and board of trustees meetings, academic and administrative department records, faculty committee reports, and records of faculty and student organizations. Graham, along with former University Historian Cecelia Moore ’13 (PhD), relied on the archives to produce their 2020 reference book UNC A to Z.

a necessary interruption

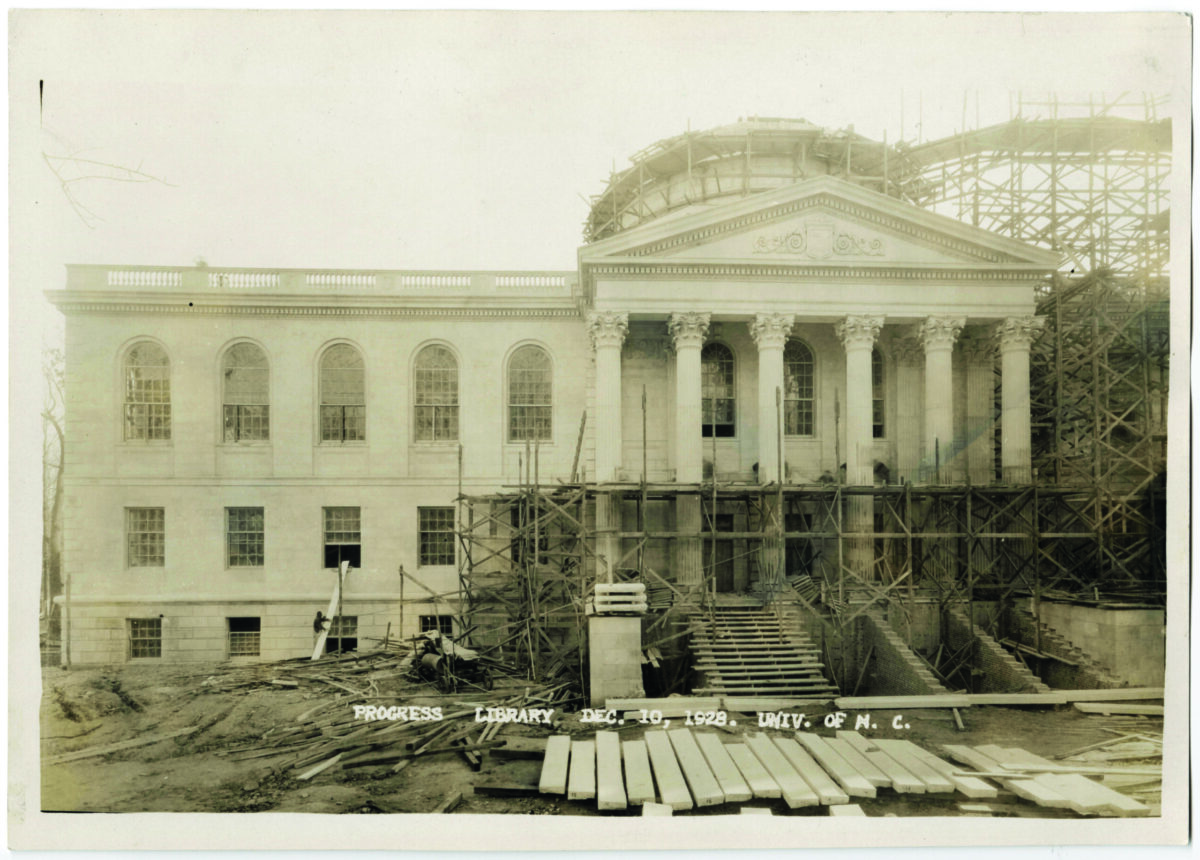

Wilson Library under construction, 1928 (Photo: UNC Library)

In 2008, the N.C. Department of Insurance notified Wilson Library administrators that the 546,393-square-foot structure couldn’t begin any construction because it was in violation of building codes, particularly regarding fire safety. The University updated the library’s safety standards and added some sprinklers, mostly in the stacks, allowing the building to continue operating.

But additional work needs to be done if the library wants to make more extensive renovations that will, as University Librarian María Estorino said, unlock the future of Wilson Library. In 2021, the General Assembly appropriated $25.4 million for renovations, and the University set aside an additional $5.8 million.

Construction will focus on three areas: additional egress staircases on the back of the building, upgrading fire alarms and extending sprinkler coverage to the entire library. Sprinklers are primarily being added within the stacks that house the special collections. “Wet materials are salvageable, burnt materials are not,” Estorino said during a November Employee Forum Zoom meeting explaining the renovations.

The upgrades will bring the entire building up to code, lifting the 2008 building restrictions and allowing the library to expand in the future.

Because the project will involve disruptive equipment, personnel must vacate the library, and all materials must be removed. The special collections will be unavailable beginning in August as librarians pack millions of linear feet of archival materials and transport them to climate-controlled offsite storage.

“Dust, debris and exposure can present hazards for library and archival collections,” Judy Panitch, director of library communications, said in a statement. “A project like this also runs the risk of major construction damage, fires or flooding that could be catastrophic for library materials.”

The entirety of the special collections, which take up more than 60 percent of the library, will be moved to an undisclosed site. “It doesn’t happen overnight,” said Elizabeth Ott, interim director of Wilson Library. “We see the good, the bad and the ugly of working in a historic building. So, I think for many of us, there’s excitement around seeing this building cared for and invested in.”

The special collections may become inaccessible in August, but the library plans to remain open for study, meetings and special events until early 2025. Most Music Library collections and services will be available through other campus libraries. Staff offices and the Center for Faculty Excellence will be relocated to temporary office spaces. The library will reopen in 2027.

But the University Archives contain more than just official University documents. Alumni donate old photos, scrapbooks and other materials, which the library has used to create what it calls a “campus ephemera collection,” Graham said. The archive includes items such as flyers, brochures, posters and class projects — essentially anything that might have been found on a bulletin board. One of the oldest in the collection is a class reunion invitation sent in 1918 to various classes celebrating notable anniversaries that year, including its original envelope and an accompanying list of the class of 1893. The collection also includes footage taken by Frank Carter ’72 for a class project at the Jubilee music festival in 1970, at which artists including James Taylor and B.B. King performed in Kenan Stadium. (See “Lend Me Your Ears and I’ll Sing You a Song,” July/August 2021 Review.) Graham said they give a human snapshot of student life that official records cannot.

When Silent Sam was toppled in 2019, activists and attorneys relied on materials stored in the University Archives to inform students, alumni, the administration and state lawmakers why the Confederate statue was erected and what leaders said about it at the time, said Graham, who added that the debate over the statue proved to him that the stewardship of campus history is not a didactic, antiquarian project. Rather, it is vital to understanding contemporary issues and debates that continue on campus today.

The University Archives also provide an avenue for local discovery. Graham came across a fascinating complaint while searching the records of the chancellor’s office: a multi-page letter from the distinguished English professor and novelist Doris Betts ’54 grumbling about her commute from her home in Chatham County and the difficulty of finding parking on campus.

Wilson Library has a small collection on Bill Neal, a chef who co-founded Crook’s Corner on West Franklin Street in 1982. The collection includes his famous recipes, handwritten by Neal himself.

Recently, the Athletics Information Office transferred 90 years of records to the archive, including press releases, newspaper clippings, game programs, statistics, media guides, photographs and scrapbooks documenting sports at the University from 1890 to 2018. The collection includes more than 200,000 individual items and takes up 387 linear feet of shelving — a good bit longer than a football field.

Elizabeth Ott, interim associate university librarian for special collections and director of Wilson Library, left, and Adrienne Bell, senior conservator, examine a first-edition 1543 copy of Andreas Vesalius’ anatomy book, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem, in Wilson Library’s conservation lab. (Photo: Carolina Alumni/Ira Wilder)

The N.C. Collection, which contains about 300,000 printed books and thousands of artifacts, is one of the largest collections of state-based records in the country, according to Ott. Highlights are on display in the N.C. Collection Gallery in the east wing of the building.

Linda Jacobson, keeper of the gallery, has a favorite: a Sir Walter Raleigh portrait painted near the turn of the 17th century. Ott admires a replication of an early 19th-century plantation library, which contains roughly 1,800 volumes, including novels, medical books and agricultural books. “It really shows you how a family in North Carolina read,” Ott said. “A library like this would have been for the family. Everyone would have read the same books. They might have read them aloud in the evening for entertainment to one another. So, it tells you something about their life.”

Students engage with archival materials more intimately when they see the physical details, Ott said. Special Collections Engagement Librarian Nadia Clifton ’19 (MSLS) said she enjoys working with pieces that have obviously been well-used. “Maybe they have notes in the margin, or a stain that looks like it’s from a cup or something on the cover, or some sort of personalization,” Clifton said.

Without these primary details, available only in physical sources, researchers and students struggle to get a holistic understanding of the past.

Classes visit Wilson Library to learn more about a subject than can be learned through digital research. Clifton always tells students to “touch a book, turn a page.”

“A lot of them are like, ‘Oh, this book is like 400 years old. I don’t want to touch it. I don’t want to rip a page or anything,’” Clifton said. “I’m like, ‘No, these books have been around for 400 years, they’ll be around for 400 more years.”

“Toward the shore dimly seen”

Guiding students and researchers into the material past is a key job requirement for Wilson librarians. They give academics from all fields of study a historical perspective on humanity they might not get elsewhere. Alexander Heard ’38, former dean of the graduate school, summed it up this way at a rededication ceremony of Wilson Library in 1988 celebrating its most recent renovations: “Wilson Library harbors raw records of people’s lives — chronicles of their personal suffering and triumphs, of their collective defeats and attainments, registers of their myths and humors and precepts, of their notions and thoughts and ideas, of their ambitions and disappointments and celebrations — all of immense utility for a society’s citizens to understand as they struggle, in faith, toward the shore dimly seen.”

Library FELLOWSHIPs

Mark Brown Jr., a master’s student in studio arts, was a 2022–23 Incubator Award recipient. (Photo: Wilson Lib./Mark Brown Jr.)

Wilson Library offers funding for teaching and research fellowships for graduate and undergraduate students, faculty, independent scholars and artists. The fellowships allow them to use the collections in a deep and intensive way.

“That’s the beauty of these sorts of fellowships. It’s speculative in so many ways,” said Matthew Turi ’04 (MSLS), the manuscripts research and instruction librarian. “It’s speculative in the sense that they’ve never used these sorts of materials. They’re imagining what they’re going to find.”

The Incubator Award, available to undergraduate and graduate creatives, was conceived by Elizabeth Ott, interim director of Wilson Library, and Alice Whiteside ’10, head of the Sloane Art Library. Award recipients use the collections in a nontraditional way to bring about some creative product — like a multimedia poetry book, a community-curated playlist or a recreation of an 18th-century apothecary shop. In recent years, the award has been given to playwrights, photographers, material artists — even tarot card readers.

Other fellowships support recipients with primary sources in teaching, the Rare Book Collection and Southern studies, some of which are designed for doctoral students and visiting researchers.

Though the library is seen by many as a “research lab for the humanities,” Graham said, it’s also provided valuable experiences for science students. Wilson hosts an annual Anatomy Day, when UNC medical students come to look at anatomy texts housed by the rare book collection, dating back as far as De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem, by Andreas Vesalius, published in 1543. The event allows students to learn about historical representations of the human body over centuries.

Part of the collection includes books donated by Carl Gottschalk, a nephrologist and a professor of medicine and physiology at UNC from 1952 to 1995. In 1998, his widow, UNC cell biology and physiology professor Susan K. Fellner, donated his personal collection and his kidney-shaped desk, both of which are now in the Fearrington Reading Room. Gottschalk presented a report to the U.S. Senate on the life-saving benefits of dialysis, which led to Medicare covering the treatment. Private insurers soon followed.

Fritz-Morkin brings her students to the library often to engage with rare Italian literature. “We had students from Italy, new PhD students this year, who had never spent time with medieval manuscripts or facsimiles,” she said. “And, for them to get that hands-on contact, without having a lot of training beforehand, really changed the way the rest of our course went.”

One of her classes visits the library three times a semester to research an uncatalogued Italian manuscript, a project that counts for more than half of each student’s grade. With the upcoming renovations, that likely won’t be possible. “I’ll have to rewrite the second half of my course,” she said.

University Librarian María Estorino has often heard Wilson’s collections described as a treasure chest, but she has a different perspective. “I feel like there’s another way to think about them — which is more as a toolbox, which seems less glamorous,” she said. “But I like to think about it in that way because of what those collections make possible, the things that people can do because of those collections.” (Photo: Carolina Alumni/Ira Wilder)

History professor Hunter is also disappointed that for the next few years his students will miss the experience of cracking open an archive folder and examining handwritten Civil War letters, among other pieces of Southern history. “Wilson Library is probably one of the best places in the country to study Southern history — not just North Carolina history — Southern history generally,” said Hunter, who has spent more than a decade teaching the subject.

Hunter earned his doctorate from Pennsylvania State University, but he knew Wilson was the place to go to answer the questions he was researching. Several times, he made the eight-hour drive to Chapel Hill to spend a week on campus to immerse himself in the Southern Historical Collection, an archive of the American South.

Hunter is working on a project about free Black men’s labor during the Civil War in North Carolina — who they were, what they were doing and why they were doing it. In the Southern Historical Collection, he found a Confederate engineer’s log book, which recorded the duties and names of 100 free Black men who worked at Fort Macon. Until now, no academic has studied in depth what these men did and why. The records in the collection don’t provide direct answers to Hunter’s questions, but they’re a road map to other records about the men, such as those kept by the Census Bureau. “There’s so many people in North Carolina history who don’t leave a written record themselves,” Hunter said. “And one of the ways that we can get at it right is through the records that others leave of them.”

Matthew Turi ’04 (MSLS), the manuscripts research and instruction librarian, mentioned an example of a random discovery that Sally Wolff-King, a scholar of Southern literature at Emory University, made in the early 2000s when immersed in the Southern Historical Collection. Wolff-King was studying the Francis Terry Leak papers, a collection of 19th-century ledgers and journals kept by the Mississippi plantation owner and enslaver. The family had donated the papers to Wilson in 1946. While reading the materials, Wolff-King, who had studied the Southern writer William Faulkner, recognized similarities between the Leak papers and Faulkner’s novels. Wolff-King’s later conversation with Leak’s great-great grandson revealed Faulkner’s frequent visits to the family’s home during the 1930s. Wolff-King determined Leak’s ledgers inspired many of Faulkner’s Pulitzer-winning novels. The New York Times reported in 2010 that it was “one of the most sensational literary discoveries of recent decades.” Wolff-King called it “a once-in-a-lifetime literary find.”

In 2021, Wilson Library acquired a biblical and Islamic manuscript from Omar ibn Said, a 19th-century enslaved Islamic scholar renowned for his Arabic writings. The acquisition is the only known Arabic autobiography written by an enslaved person in the United States. Said was enslaved in North Carolina, and his slaveholders had affiliations with the University, so he likely spent time on campus, The Daily Tar Heel reported.

A toolbox

John Loy, a preservation audio engineer who has been with the Library for more than 20 years, processes a midcentury Kitty Wells tape in the John L. Rivers studio, a fourth-floor space just behind Wilson Library’s dome. (Photo: Carolina Alumni/Ira Wilder)

Omar, a Pulitzer Prize-winning opera based on Said’s life, premiered on campus in 2023. One of the opera’s creators, singer-songwriter Rhiannon Giddens, who is completing a two-year research residency at the Carolina Performing Arts, studied Said’s texts after the acquisition. An integral part of her studies involves combing through the archives for items that document interracial sentiments during the 1800s, especially the decades following emancipation. But Giddens, a Grammy-award winning folk musician, is not new to Wilson Library. Her former band, the Carolina Chocolate Drops, got its start in Wilson’s Music Library.

Shortly after it formed, the band came to the library to research the Black string-band music tradition. They dove into the Wayne Martin and Nancy Kalow Collection, which includes video recordings of Black fiddlers and string-band musicians. The group discovered artists such as Joe and Odell Thompson and refined their repertoire. Steven Weiss, curator of the Southern Folklife Collection, said he was “chuffed” to see how a seed that was nurtured by the collections eventually led the group to a Grammy Award. Now there are articles about the Chocolate Drops in the archives, and Dom Flemons, who co-founded the group with Giddens, later added his own papers to the special collections.

Estorino has often heard Wilson Library’s collections described as a treasure chest, but she has a slightly different perspective. “I feel like there’s another way to think about them — which is more as a toolbox, which seems less glamorous,” she said. “But I like to think about it in that way because of what those collections make possible, the things that people can do because of those collections.”

For Turi and other library staff, Wilson Library’s mission is to do exactly that, provide access to collections to support the public in any endeavor. “As somebody that works on the access end of special collections, it’s always been deeply gratifying to me that the mindset in the building isn’t really one of being a ‘guard’ or a ‘keeper of order,’ ” Turi said. “It’s one of collections for use.”

Ira Wilder is a senior from Henderson, majoring in public policy and journalism. He is a Morehead-Cain Scholar and an intern for the Review.

Corrections: A previous version of this article reported the N.C. Digital Heritage Center partnered with N.C. State University. The center partners with the State Library of North Carolina, not NCSU. The article reported the oldest document in the University Archives is dated 1757. The document is a copy and is in another collection, not the University Archives. The article reported Wilson Library stores parking records. It does not. The reference to parking was in a letter filed in the records of the chancellor’s office.