Kuralt, in Full

On the 25th anniversary of a legend’s death,

a Carolina alumna shares what she found

when researching his work.

by Claire Cusick ’21 (MA)

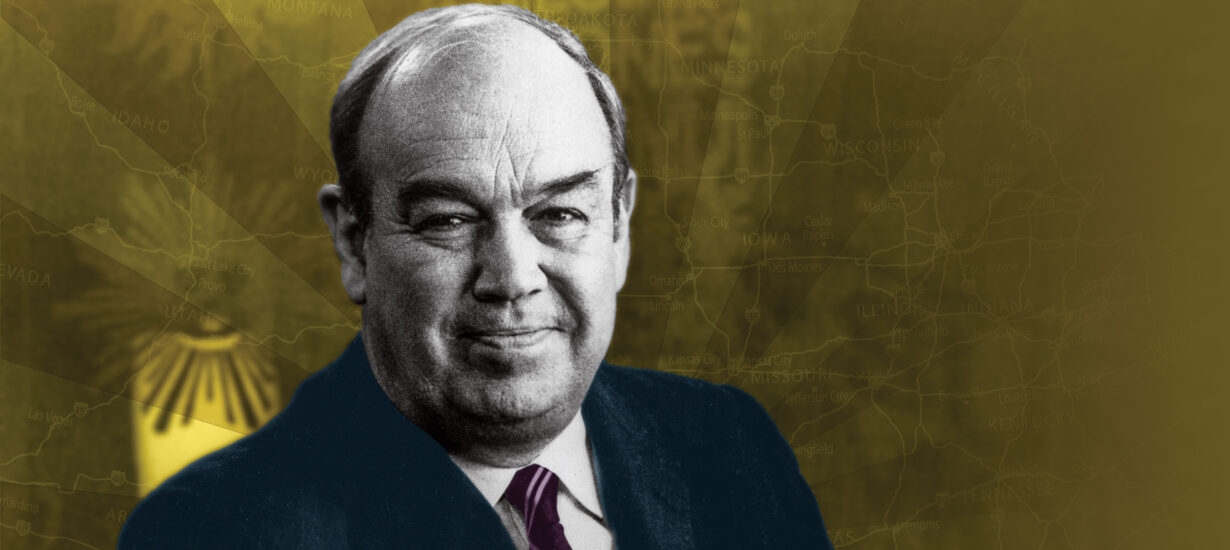

It’s his voice that lingers the most. That singular baritone reciting the poetic lines of his 1993 speech — “What is it that binds us to this place, as to no other?” — became seared on the brains of Tar Heels of all ages once the University began using it in a national television commercial a year later.

Twenty-five years after his death, Charles Kuralt ’55 remains bound to Carolina, just as he posed during his iconic speech honoring the University’s Bicentennial in 1993. He is buried in the Old Chapel Hill Cemetery off South Road. Students and alumni can see the name Kuralt when walking across campus. The School of Social Work’s Tate-Turner-Kuralt building is named, in part, for Wallace Kuralt Sr. ’31, his father, a longtime social worker. The Charles Kuralt Learning Center in the Hussman School of Journalism and Media is essentially his New York office, shipped to Chapel Hill and reassembled after he died on July 4, 1997.

But most current undergraduates weren’t alive then, and wouldn’t likely remember another white guy from television’s analog era, before the internet. And even among those who do remember him and his work, he is talked about in simplistic but glowing terms:

Wasn’t he great?

He was great.

He sure did love Carolina.

I was a twentysomething business reporter at The Herald-Sun in Durham when he died. I wanted to be like him: to tell inspiring stories about so-called “regular people” all across America. I snuck into his memorial service with a colleague who was there to cover it. And in the years since, I’ve studied his methods and output. My master’s thesis in folklore at Carolina is only the third academic paper written about him. I learned he was a gifted storyteller, a prodigy and a workaholic who often downplayed his ambition and talent. He loved sound and often used it to tell stories, even in the visual medium of television.

Maybe after 25 years, it’s time to share a fuller picture of Charles Kuralt.

Even among those who do remember Kuralt and his work, he is talked about in simplistic but glowing terms.

KURALT’S UNC

COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS

May 12, 1985

(excerpted)

“I am a Tar Heel born and a Tar Heel bred, and when I die I am a Tar Heel dead — but this is my first Chapel Hill Commencement. I did not quite qualify for attendance at the graduation of my own class. …

“I left Chapel Hill on a spring day like this one thirty years ago. … Thirty years is a blink of an eye in the long story of the human race, but it is a long time in the life of our nation. Thirty years ago, on graduation day, we were just beginning to think about the deep racial injustices that existed in our country, and especially in our native region. We had not yet begun to think about the attitudes and laws which were unfair to women. We had no particular awareness of the strains we were putting on the environment; ‘ecology’ is a word I believe I had not heard. …

“We have come a good long distance in thirty years, and we may have come by many different ways, but the main way was learning to care about one another. We still have a long way to go, and since you ask my advice, here it is: Care about one another. …

“This University knows that ignorance will have its innings, but will always lose in the ninth. … Care about one another, and not only those of your own clan or class or color. I wish you long life and good fortune, of course. But my warmest wish for you is that you be sensitive enough to feel supreme tenderness toward others, and that you be strong enough to show it. That is a commandment, by the way, and not from me.

“I believe it is also the highest expression of civilization.”

— Charles Kuralt ’55

The rhythm of language

Kuralt grew up listening to Southern storytellers, both Black and white. He loved the sound of the spoken word. Consider the 1985 album North Carolina Is My Home, which he wrote with musician Loonis McGlohon to commemorate the state’s 400th birthday. Kuralt devoted an entire section to the names of North Carolina places and the stories behind them:

Far from home, my mind embraces, the nimble names of Tar Heel Places:

Topsail Sound and Turner’s Cut

Dixon and Vixen and Devil’s Gut.

Hoke, Polk, Ashe, Nash. Calico. Calabash.

Kuralt credited his grandmother, a teacher in Onslow County, with sparking his love of the spoken word. “She taught half the children in that part of the county to read, and she read to me from the travel books of Richard Halliburton and the short stories of O. Henry and the poems of Kipling and Poe,” he said in 1993 when he accepted an award from the North Caroliniana Society, which promotes the appreciation of North Carolina’s heritage. “I do believe I gained a love of words and the rhythm of language from my grandmother, Rena Bishop.”

In that same speech, Kuralt spoke about Rosa (he did not give her last name), “the patient, beautiful, young Black woman who was my baby-sitter, whom I loved, and who loved me too, and who told me stories, and made me apple butter, and was right about everything.”

He also recalled riding in the car with his father. “We stopped for suppers of pork chops, sweet potatoes, and collard greens at roadside cafes, and rolled on into the night, bound for some tourist home down the road, my father telling tales, and I listening in rapture, just the two of us, rolling on, wrapped in a cloud of companionship and smoke from his five-cent cigar.”

It’s true that Kuralt had blazing talent. But talent is just one part of greatness, which comes from dedicated practice. Kuralt committed to his craft from a young age.

“I can’t remember a time when I didn’t want to be a reporter,” he told an interviewer for the American Academy of Achievement, which brings together leaders in different fields, in 1996. “From the first or second grade, I thought that’s what I wanted to be, a reporter. A newspaper reporter, of course, because there was no television yet. And I never changed my mind.”

When he was 9 years old, Kuralt started a neighborhood newspaper, The Garden Gazette. He began an on-air radio job at 13 and entered UNC at 16. When CBS hired him to write for radio at 22, Kuralt had already won national writing awards, including the Veterans of Foreign Wars’ “Voice of America” speechwriting contest when he was 14, and the Ernie Pyle Award for columns he wrote at The Charlotte News.

During high school in Charlotte, he covered prep sports for one of the local newspapers and worked at WAYS as a disc jockey and newsreader. “I couldn’t wait for school to be out so that I could go uptown, about a mile away and go to work,” he said in the interview with the Academy of Achievement. “I loved working.”

In that same interview, Kuralt reflected on the beginnings of a life spent choosing work over everything else. “I missed a good deal, I think. I certainly didn’t pay as much attention in class as I should have,” he said. “My family would take family vacations, but I’d always stay home, because I didn’t want to miss out on the work.”

The pull to work continued while he served as editor of The Daily Tar Heel during his senior year. “[T]he newspaper used up so much of my time that I started dropping courses,” he wrote in his 1990 memoir, A Life on the Road. “By the time the spring quarter arrived, I had dropped them all. … Graduation proceeded without me. I didn’t care. I had found my career.”

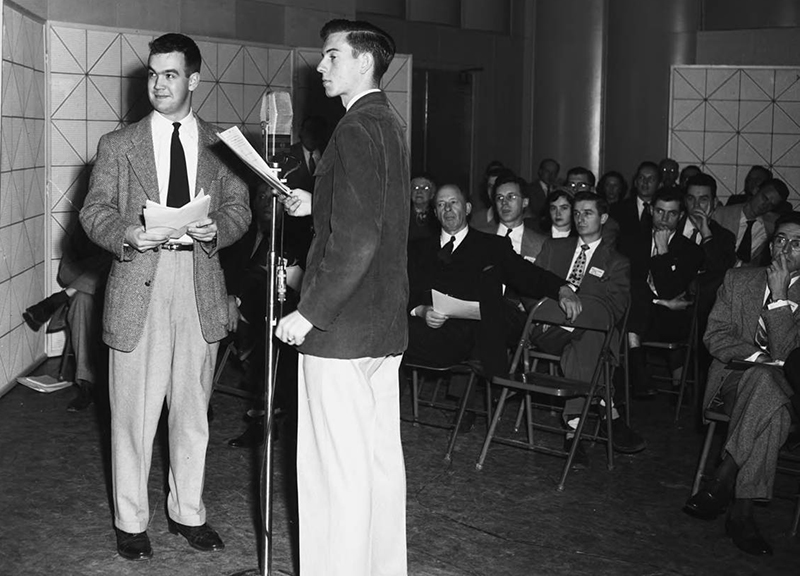

Kuralt (left) and Carl Kasell ’56 performed a radio dramatization during the dedication ceremonies for WUNC Radio on March 13, 1953. Photo: UNC Photo Lab Collection #P0031, N.C. Collection, UNC

Lifelong love for radio

Kuralt had a special fondness for radio. In 1996, in his acceptance speech for the Television Academy Hall of Fame, he recalled the radio in his grandparents’ farmhouse, a Depression-era, “battery-powered, floor-model, Montgomery Ward radio in the shape of a Gothic arch, with a great round dial that glowed orange when you turned it on.” As a young boy, he “sat there on the floor before that glowing dial, listening to voices come out of the air.”

In 1995, he bought an AM-FM station in Ely, Minnesota, for $37,000, rescuing it from receivership. At the time, he promised to fill in occasionally for the general manager of the station — WELY, better known as “End of the Road Radio.” It’s not clear whether he ever made it back to Ely to fulfill his promise before he died two years later.

His first job at CBS had been writing for radio, working the overnight shift, making $135 a week to compile wire-service reports and CBS bureau dispatches into an ever-changing script that an announcer read at the top of every hour. Within a year, he was promoted to television, first as a writer, then as a correspondent.

For the next 10 years, CBS sent him all over the world as a general assignment reporter. He also covered hard news in the United States — political conventions, the Freedom Rides and poverty in Appalachia. He interviewed Marilyn Monroe, Nikita Khrushchev and Che Guevara. He watched 6-year-old Ruby Bridges walk into an all-white school in New Orleans in 1960. He was in the press corps that followed Ambassador Adlai Stevenson on a tour of South America. He reported a one-hour documentary about an expedition to the North Pole. In his first trip to Vietnam, Kuralt was standing in a clearing with a Vietnamese soldier allied with the United States when the man was shot in the head by a single bullet fired by a sniper hidden in the trees. Kuralt tried to stop the bleeding with a handful of leaves, as the man died.

“I was drunk with travel, dizzy with the import of it all, and indifferent to home and family,” he wrote in his memoir. “Pretty soon, I no longer had a home or family.” Shortly after the birth of their second daughter, Kuralt’s first wife, Sory Guthery Bowers ’55, filed for divorce.

But by 1967, Kuralt had grown weary of travel and hard news. “I had known from the beginning that I was better suited to feature stories than to wars, polar expeditions, politics and calamities,” he wrote in his memoir. “I had worked 10 years for CBS News, often on assignments that taxed my physique and temperament.”

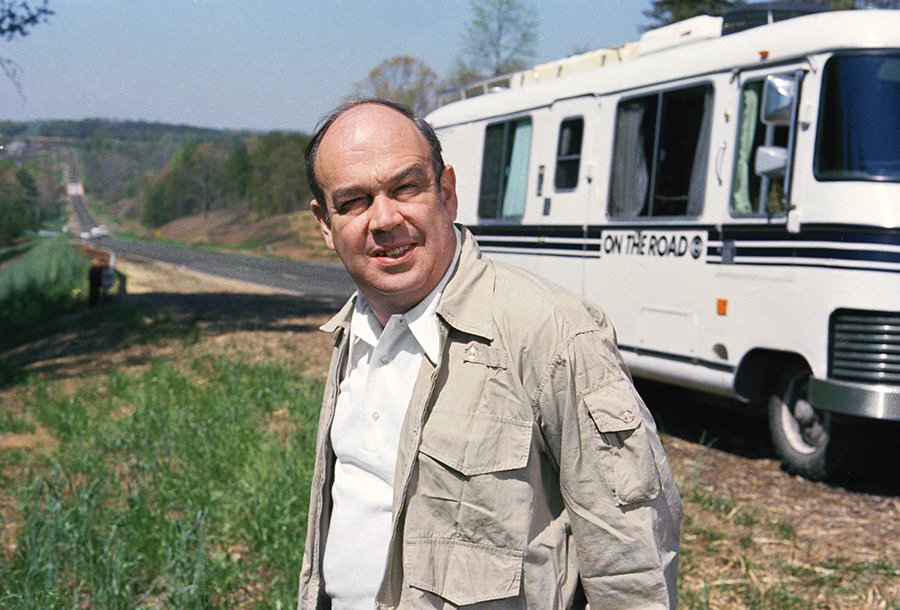

What Kuralt pitched to CBS in 1967, and was initially approved as a three-month project, became a favorite of American households for more than a quarter century. Kuralt reportedly logged over a million miles as he crisscrossed the nation’s back roads in search of stories to tell. Photo: Getty Images/CBS Photo Archive, 1979

That’s when he started what would become “On the Road,” his charming segments on hometown heroes, historic moments and inspiring characters from all 50 states. It ran on The CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite until 1980, when Kuralt helped launch his other enduring project: CBS Sunday Morning.

“On the Road” became what Kuralt was known for, rather than all he’d done before. But that didn’t concern him. “In the nature of the stories I was doing, there was very little to criticize. They were simple, innocent stories,” he said in the Academy of Achievement interview. “I thought at the time that they were successful in their own terms. I recognize that they were not vitally important ones, but I don’t think the occasional criticism bothered me very much.”

Kuralt may have intentionally set out to find what was happening in America beyond the headlines. “Journalism, by its nature, rushes about shouting,” he said in the 1986 Red Smith Lecture in Journalism at the University of Notre Dame. “The country, by its nature, moves slowly and talks softly.”

After his years of covering all manner of “shouting,” Kuralt was content to leave that work to others. “I have worked myself at the edges of the craft; it’s been a long time since I covered anything important,” he said in that same lecture. “I have tried to keep importance and relevance and significance entirely out of my work, in fact, on the grounds that with everybody else covering the Senate hearings, somebody has to cover the greased pig contests and the guy who has a car that runs on corncobs,” he said. “And that’s been me.”

The pull to work continued while Kuralt served as editor of The Daily Tar Heel during his senior year. “The newspaper used up so much of my time that I started dropping courses,” he wrote in his 1990 memoir. “By the time the spring quarter arrived, I had dropped them all. … Graduation proceeded without me. I didn’t care. I had found my career.”

Oral performance on TV

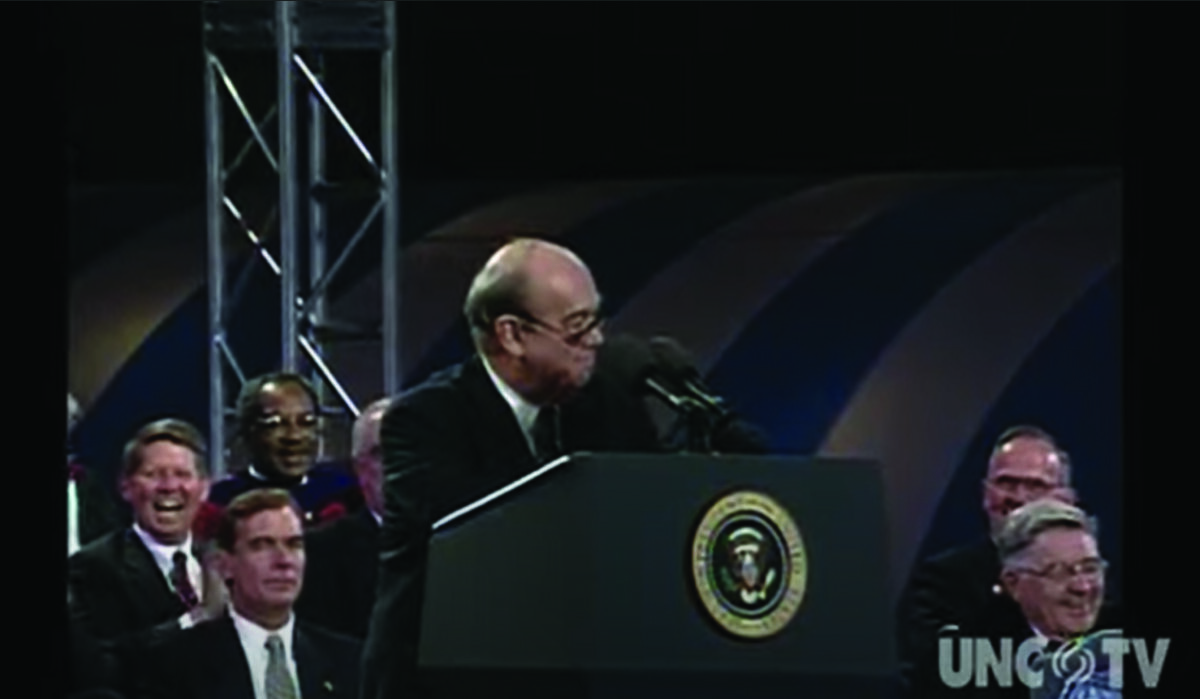

President Bill Clinton awarded Kuralt the National Humanities Medal in 1995. Kuralt’s papers are archived at Carolina’s Southern Historical Collection. Photo: AP Images/Tim Rue

Journalists or aspiring podcasters and writers could learn a lot from studying Kuralt’s work. He was a superior writer and master storyteller, and some “On the Road” segments could be considered brief essays delivered as a spoken performance. “This is a story about Napoleon, and Jefferson, and Talleyrand, and foreign intrigue in Paris, and an empire changing hands,” Kuralt intoned in one segment, standing in a gray jacket against a gray backdrop of bare trees in winter. “And this is the best place to tell the story: a swamp in Arkansas.”

In that piece, Kuralt wrote and narrated a script of less than 600 words to convey not only the story of the Louisiana Purchase — the 1803 land deal that nearly doubled the size of the United States — but also the reason he chose a swamp as the place to tell it. His only visual flourish is one cocked eyebrow as he starts his narration. Then, as he slowly walks down a wooden footbridge unspooling a tale, the mystery of the location follows him. At the end of the story — and the footbridge — the camera shifts to show a granite marker, and Kuralt reveals its significance: It’s a survey marker.

“If you live today in Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Minnesota, your township boundaries, your section lines, the boundaries in your lot are based on this stone in the middle of a cypress swamp in Arkansas,” he said. “This stone is a symbol of the American urge, the strongest urge in our history, to cross the rivers and head west. It’s a symbol of the American itch to own a piece of land, to have it and hold it, enough for a flower garden, or enough for a cattle ranch.”

Kuralt brought his love of sound to the visual medium of television. He celebrated it throughout “On the Road” with stories about bandleaders and auctioneers and stone skippers. When Kuralt visited the Avedis Zildjian Co. in Quincy, Massachusetts, which manufactured cymbals, he seemed to choose it specifically for the onomatopoeia it provided. Before relaying the story of the Armenian American family who had been making the instruments since a metallurgy discovery in Constantinople in 1623, he asked the company’s owner, Armand Zildjian, about all the loud product testing going on.

Zildjian: They’re selecting the proper cymbal for the orders. … We have many types of cymbals. We have ride cymbals, bounce cymbals, played with the tip of the stick, we have cymbals for crash, crash-ride cymbals, bebop-ride cymbals, swish cymbals, pang cymbals, sizzle cymbals …

Kuralt: Swish, pang and sizzle?

Zildjian: Right.

Kuralt is remembered for producing charming, light-hearted, smile-inducing work. He often was labeled as “folksy” and “avuncular,” but he was a complicated human being, just like the rest of us. After he died, it became public that he had a 30-year relationship with Patricia Shannon, while married to his second wife, Suzanna “Petie” Baird Kuralt.

Neighborly, just, humane

Kuralt is buried beside his wife, Suzanna “Petie” Baird Kuralt, in the Old Chapel Hill Cemetery off South Road. He willed most of a Montana property to Patricia Shannon, with whom he had a 30-year relationship. Photo: Wikimedia/Mx. Granger

Kuralt is remembered for producing charming, light-hearted, smile-inducing work: the world’s largest ball of twine, the Iowa farmer who built a boat in his front yard, the town whose residents came together to fill its potholes. He often was labeled as “folksy” and “avuncular,” but he was a complicated human being, just like the rest of us.

After he died, it became public that he had a 30-year relationship with Patricia Shannon, while married to his second wife, Suzanna “Petie” Baird Kuralt. He had met Shannon when he featured her in a 1968 “On the Road” story. A year before he died, he had willed most of a Montana property he owned to Shannon. On June 18, 1997, he wrote her a letter, indicating he wished her to inherit the rest of the property. She brought that letter to his funeral in Chapel Hill and began a challenge to his estate. The legal case deciding whether Kuralt’s letter constituted an executable will continued all the way to the Montana Supreme Court, which ruled in Shannon’s favor in December 2000.

Nor did Kuralt completely abandon the reporter in him that took on important issues, as he claimed he had in that 1996 interview with the American Academy of Achievement. Kuralt loved American history but didn’t ignore its painful chapters. The man who had championed integration when he was editor of The DTH produced a 1977 “On the Road” segment about the lawyer, civil rights activist and Episcopal priest Pauli Murray. In it, he addressed her heritage with clear eyes and plain words.

“This is a story of triumph, but it begins with pain and disgrace,” he said at the start of the segment. “It begins, to speak plainly, with a rape. The rape was committed in the days before the Civil War by a wealthy young North Carolina lawyer named Sidney Smith. His victim was a young slave woman. Nothing unusual about that in the sorry annals of slavery.”

Kuralt also produced a story on the Battle of Little Big Horn, also known as the Battle of the Greasy Grass. U.S. Lt. Col. George Custer, hundreds of U.S. soldiers and dozens of Native Americans died there on June 25, 1876. “This is about a place where the wind blows and the grass grows and the river flows below a hill,” Kuralt said in his script. “Nothing is here but the wind and the grass and the river. But of all the places in America, this is the saddest place I know.”

But it’s true, just like people say, that he was great at what he did. And yes, he sure did love Carolina. Just before the oft-quoted part of his UNC Bicentennial speech, Kuralt’s opening spoke for everyone gathered in Kenan Stadium that crisp October night: “We are Tar Heels born and Tar Heels bred, and we are glad to be alive on the 200th anniversary of the establishment of public higher education in the new world, and immeasurably proud that this occurred Oct. 12, 1793, on the crest of New Hope Chapel hill.”

Perhaps, on this 25th anniversary of when his voice went silent, we can remember that wandering the back roads and the small towns of our nation bolstered Kuralt’s faith in America. “After all these years of meandering through it … I believe the country to be more neighborly, and more just, and more humane than you would think from reading the papers or watching the evening news,” he said in the Red Smith lecture. “The country I have found is one that presses upon the visitor cups of coffee and slices of pie … and doesn’t bear much resemblance to the country that makes it to the front pages, which have room only for wars and politics and calamities … and not enough room for telling the story of people living and working and trying to be good neighbors. But that country is there, as we all know.”

The Speech That Almost Never Was

“And so in time I came here, as my father had done before, and my brother Wallace after, and here we found something in the air. A kind of generosity, a certain tolerance, a disposition toward freedom of action and inquiry that has made of Chapel Hill, for thousands of us, a moral center of the world. … Two hundred years to the day since the founding of the first state university, we can read again the words on its seal — light and liberty — and say that the University of North Carolina has lived by those two short noble words, and say that in all the American story, there is no other place like this.” — Charles Kuralt ’55. Photo: YouTube/UNC TV

It was Oct. 11, 1993, the day before Carolina was scheduled to hold one of its biggest celebrations: the University’s Bicentennial. Those planning to attend included a long list of dignitaries, including President Bill Clinton, Gov. Jim Hunt ’64 (LLBJD), former Sen. Terry Sanford ’39 (’46 LLBJD) — and Charles Kuralt ’55, who was scheduled to give a speech.

But Kuralt almost didn’t make it to Kenan Stadium, where a capacity crowd would gather the next night. His father, Wallace Kuralt Sr. ’31, was in a hospital in Elizabeth City. The day before the Bicentennial celebration, Kuralt told planners he didn’t want to leave his father’s bedside, and the drive to and from Chapel Hill would keep him away for too long.

So UNC System President C.D. Spangler Jr. ’54 sent his plane, a Beechcraft King Air 200.

Spangler’s personal pilot at the time, Alan Fearing, confirmed that he picked up Kuralt in Elizabeth City and flew him to Chapel Hill, then flew Kuralt back to Elizabeth City that evening.

In a 1996 interview with The State magazine, Kuralt “chuckled at the memory,” and told writer Speed Hallman ’82, “That shows how fast you can get around North Carolina if you have the right means.”

Between the flights, in a speech that lasted just over eight minutes, Kuralt outshone the gifted orators Clinton and Hunt with a speech that became a defining moment of the celebration and for the University for decades to come. After being introduced as “one of the University’s favorite sons” by then-Chancellor Paul Hardin III, Kuralt stepped to the lectern and opened with a two-part dig at Duke University that brought rounds of applause and cheers from the crowd, and an inaudible “Wow” from Clinton.

About a minute into his speech he asked what has become the iconic question, “What is it that binds us to this place as to no other?” That led to his answer: It’s because UNC is “the university of the people.”

Kuralt then spent the bulk of his words praising former UNC President Frank Porter Graham (class of 1909). “He was a saint,” Kuralt said. “He became the spirit of the University, which he never forgot had been created for the people.”

Kuralt provided his own evidence of Graham’s sainthood: miraculous deeds. “In the midst of that Great Depression, he took the leadership of a poor university in a desperately poor state and transformed it by tact, diplomacy, iron persistence and steady strength of character into a model of public higher education and a light for the nation. If building a great university when and where he did it isn’t a miracle, then miracles don’t exist.”

Kuralt offered a short list of those “whose lives were touched and changed in this place,” including Sanford, political activist Al Lowenstein ’49, former Institute of Government Director John Sanders ’50 (’54 JD), journalist Tom Wicker ’48 and Tom Lambeth ’57, who has served in leadership roles in the education and foundation worlds, as well as chairing UNC’s Board of Trustees and serving as a member and president of the GAA Board of Directors. Kuralt concluded that there was “something in the air” in Chapel Hill that was made up of generosity, tolerance and “a disposition toward freedom of action and inquiry that has made Chapel Hill … a moral center of the world.”

Jim Copland ’94, the student body president at the time of the Bicentennial who sat on stage with the dignitaries, said, “Kuralt’s speech just defined the event for most of us there. It was just the perfect tone, everything about it.”

It was exciting to have Clinton present, but, Copland said, in the end, Clinton’s speech paled in comparison to Kuralt’s. “It was this thing where everyone was waiting to hear the President and then, you know, the first guy that talked stole the show.”

— Claire Cusick ’21 (MA)

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.