Lend Me Your Ears and I’ll Sing You a Song

Posted on July 29, 2021America crossed many cultural bridges between 1963 and 1971. One of Carolina’s — from Chuck Berry to Johnny Cash to Joe Cocker — was an unforgettable Jubilee.

by Mike Ogle ’02

Whenever hindsight travels through enough time, objects may appear both hazier and clearer. When it comes to the three-day outdoor music festival called Jubilee that was held on Carolina’s campus each spring from 1963 to 1971, plenty of reasons for both exist after 50 years.

For one, that historic period in the United States came into better focus as the decades passed. But also, well, some of you probably had, let’s say, too much fun on those fields to conjure too many of the particulars. It’s little wonder why some had to place lost-and-found ads afterward for their puppies (part Collie), kittens (calico-Siamese mix) and cameras (Kodak, 35 mm).

For one, that historic period in the United States came into better focus as the decades passed. But also, well, some of you probably had, let’s say, too much fun on those fields to conjure too many of the particulars. It’s little wonder why some had to place lost-and-found ads afterward for their puppies (part Collie), kittens (calico-Siamese mix) and cameras (Kodak, 35 mm).

Half a century later though, at least one thing is clear: Jubilee ended on a note so high it required no encore, as it seemed destined to do. Once an elephant appeared and Joe Cocker melted Kenan Stadium in 1970, Jubilee’s days likely were numbered. The rest were the details. Mind-bendingly fun and sometimes chaotic details.

But also a couple of not-so-fun ones. Fortunately, there are archives to aid memory. Jubilee’s epitaph was being chiseled from that first spring. And, following the last, “The rock festival phenomenon is dying at last,” Rod Waldorf ’71 wrote in The Daily Tar Heel.

It wasn’t just a circus animal or Cocker’s Mad Dogs and Englishmen that signaled Jubilee’s end. It wasn’t that Chapel Hill sold out of brownie mix, forcing future comedian Lewis Black ’70 to make pot pudding instead of pot brownies. (See below for more on Black’s Jubilee memories.)

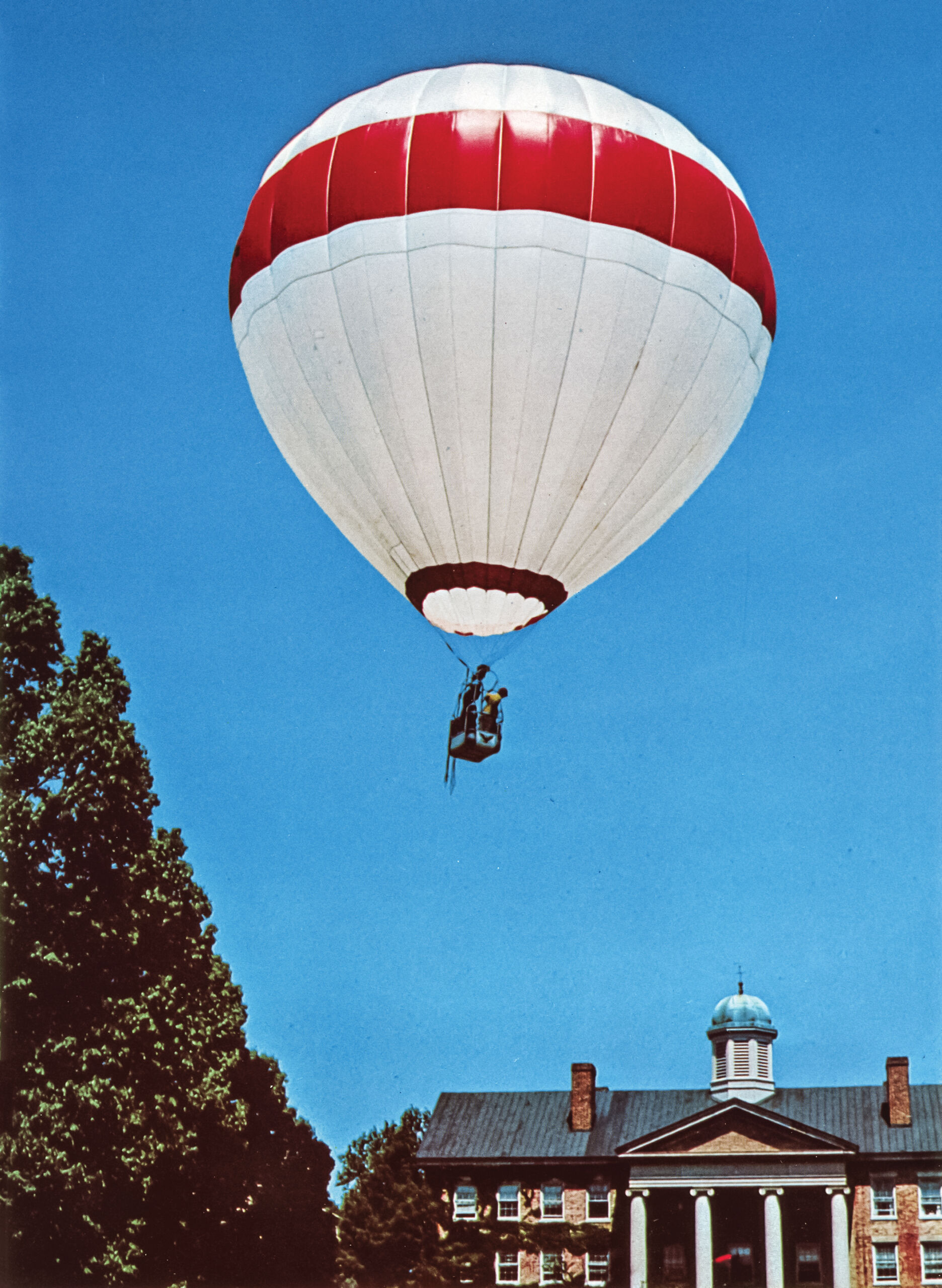

It wasn’t even the hot-air balloon ride that a Wizard of Oz look-a-like crash-landed in University Lake, or the woman injured on the Whirly-bird ride, or the straw bales and foam rubber lit on fire. It wasn’t even the trampled security guard, or Pacific Gas & Electric getting arrested on stage, or the Allman Brothers’ cocaine.

It was all the excesses that accumulated over those nine years alongside so many colliding happenings in America — rock music and the festivals, drugs, peace, love, protest, the Vietnam War and the establishment’s responses to them all — that ultimately doomed Jubilee. Like that hot-air balloon that kicked off the 1969 festival, Jubilee fell back to earth. But before gravity grabbed hold, it was one hell of a ride.

1966’s sprawling Polk Place Jubilee featured jazz guitarist Charlie Byrd. (Jock Lauterer Photographic Collection, NC Collection, UNC Libraries)

Beginnings: 1963-68

By Jubilee’s end, the festival was worthy of documenting in a film, as some radio, television and motion picture majors did. But its start was much more humble. Put on by the Student Union, Jubilee essentially launched as a modest folk festival in 1963 on a makeshift stage on McCorkle Place. Think more along the lines of college sweaters and glee club, less so bare feet and all-night Bullwinkle and Roadrunner cartoons under a cloud of skunky smoke.

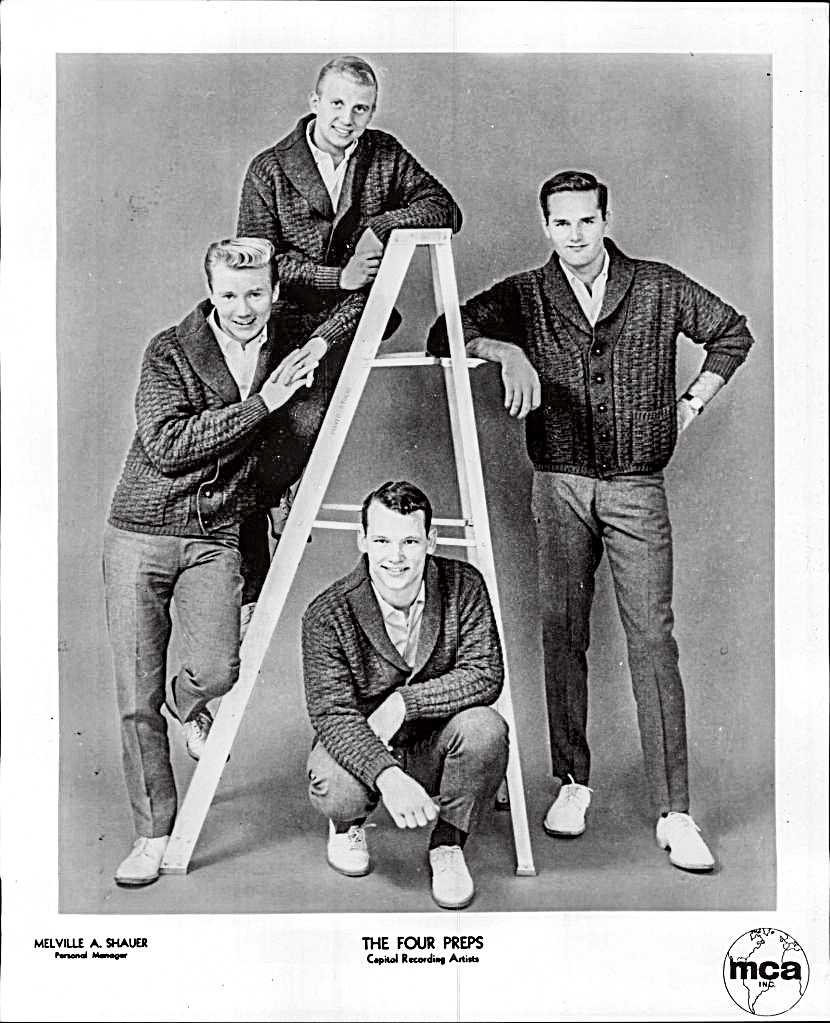

1963: The Four Preps (Capitol Records/MCA)

The Four Preps headlined the first Jubilee before a crowd of about 4,000, capping a school year when some of the Union’s big attractions were a hypnotist named Hypnorama and Hal Holbrook as Mark Twain. What came later — a jazz big band on a Saturday afternoon; smaller bands, known as combos, at late-night parties; and films featuring Liz Taylor and Sophia Loren on indoor big screens — was, by comparison, cutting loose.

Jubilee was in one sense an answer to the Germans, big cotillion-styled dances sponsored by an interfraternity system that was not open to all students in the first half of the 20th century. From the start, Jubilee was intended to be more inclusive, relatively speaking for the South at that time. Jubilee events were scattered across campus, no ticket was needed, and people could float from one party to another.

Put on by the Student Union, Jubilee essentially launched as a modest folk festival in 1963 on a makeshift stage on McCorkle Place: think college sweaters and glee club.

However, hiccups and controversy regarding who was able to attend — an issue later pivotal to Jubilee’s demise — appeared in that first year. Curfew still applied to women’s dormitories, a bummer for those combo parties. Also, only about 25 percent of Carolina students were women then, and a request to invite busloads from Woman’s College in Greensboro came too late to make arrangements. In another harbinger of things to come, the concerts drew noise complaints, and students left lots of litter behind.

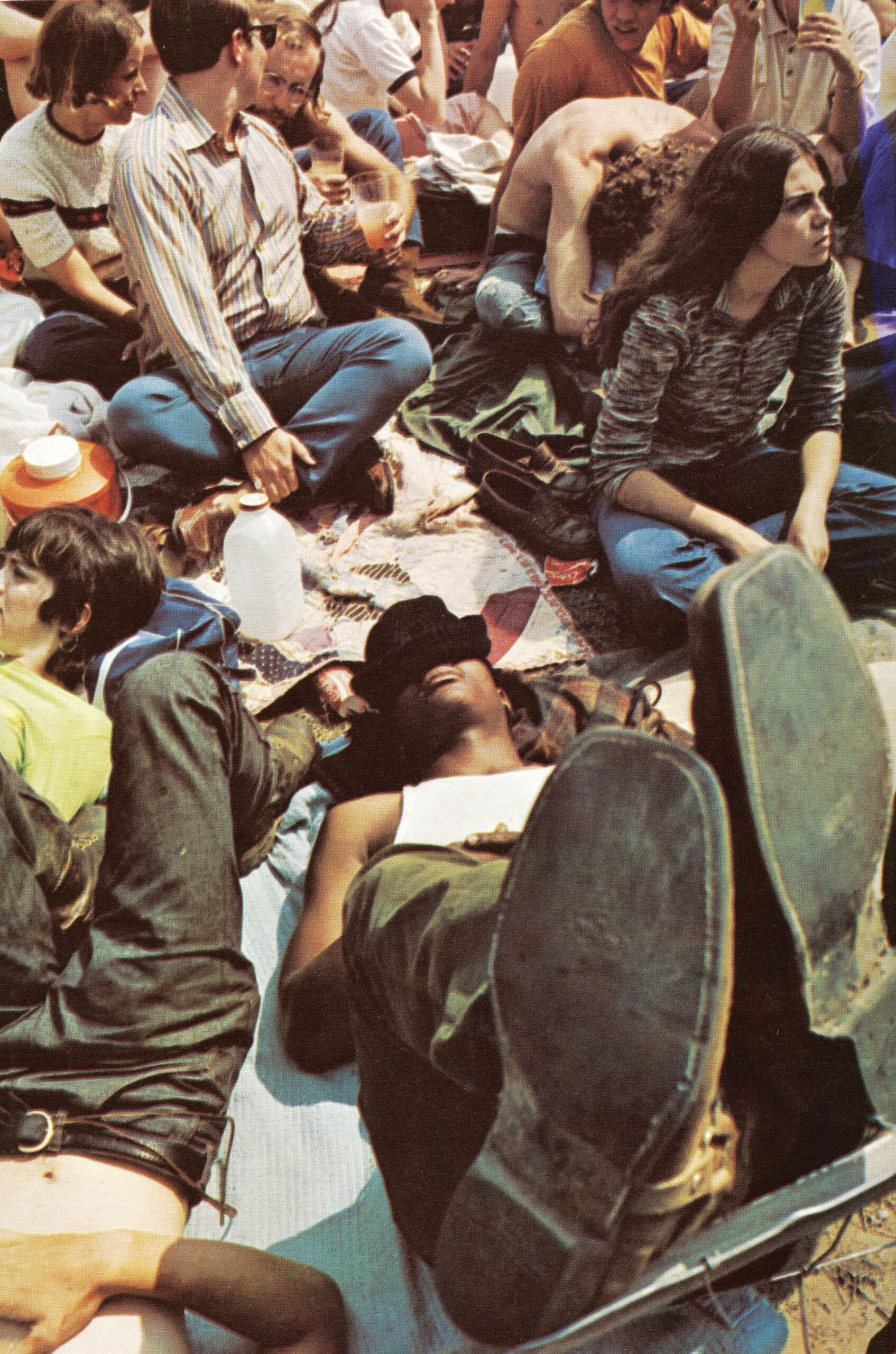

Some attendees in 1966 brought maybe just a little Kentucky Tavern whiskey. (1966 Yackety Yack)

The “salute to spring,” as that Jubilee was billed, was a blast, though. The kinks presumably could be smoothed, and Jubilee was an instant tradition. Over the next few years, it grew and migrated. The musical acts went from The Four Preps to the Statler Brothers, The Platters, Johnny Cash, Charlie Byrd, The Temptations, Petula Clark and The Association. It moved from McCorkle Place to Polk Place to Fetzer Field before going to Kenan Stadium and Navy Field, the longtime football practice site, for its final acts. As late as 1968, Jubilee was still more of a khaki affair featuring Neil Diamond.

But the times were changing quickly, and Jubilee caught up in a hurry. Carolina had hired Howard Henry as the director of the Student Union. Henry brought his contacts with talent agents in New York and the wits to negotiate with them. Soon he’d join forces with a student leader whose Union peers today call a “genius” and a “magician.”

As Jubilee got off the ground, a boy in Asheville was preparing to send it into orbit. John Haber ’70 was in the sixth grade when he founded a children’s community theater that he ran until graduating from high school. It celebrated its 60th birthday in 2019. “It was sort of in my blood,” Haber says of his event-planning acumen.

Haber entered Carolina in fall 1966, soon saw The Mamas & The Papas live in Carmichael Auditorium — his first big concert — and was hooked. He became Union president as a junior and held the position for two years to mold Jubilee in 1969 and 1970 into a giant that mirrored what was taking place in America. His knack for targeting fast-rising musical acts not yet out of reach for UNC, combined with Henry’s savvy and openness to any semi-reasonable idea, also made some cherished concert moments beyond Jubilee. Alumni from those years still rave about Ike and Tina Turner, The Temptations, Iron Butterfly and the time Janis Joplin partied at the St. Anthony Hall fraternity house after rocking Carmichael.

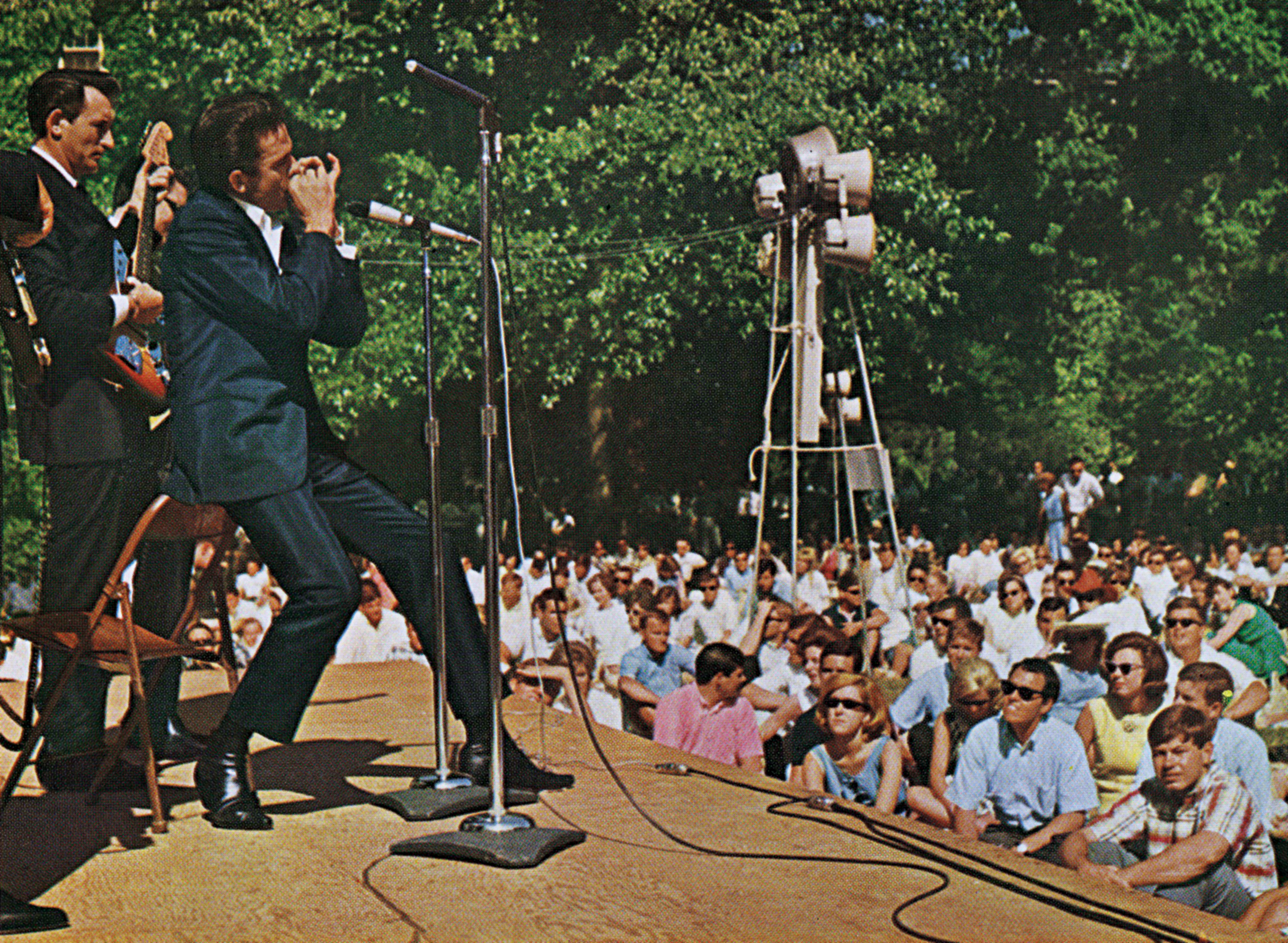

1965: Johnny Cash and the Tennessee Three (1966 Yackety Yack)

As the artists for Jubilee increased in scale, Haber and his student cohorts at the Union also got to work forging an experiential event to match. Step one was upgrading to Kenan Stadium in 1969 and remaining there in 1970 despite frictions with the athletics department. Then came carnival rides, the hot-air balloon, a sea of helium balloons, the Chapel Hill flower ladies selling homegrown daisies, pie throwing, a hog caller, a hollering champion, slip-and-slide and an elephant named Sabu that Haber booked for $1,000 after he got a solicitation from a wild animal show out of Indiana. Sabu appears briefly in a film of the event, and she may have served mainly as a photo backdrop in an adjacent area.

“John was a genius at production,” said Chuck Patrizia ’72, who became Union president after the last Jubilee. “He had big ideas and the ability to carry them off.” No idea was too wacky. The organizers even installed a charcoal oven on the field where they baked a 100-foot loaf of bread, one bit at a time, then slid the oven gradually forward. They bought the dough from a bakery in Greensboro in the middle of the night and struggled to keep it from exploding out of its box on the ride back.

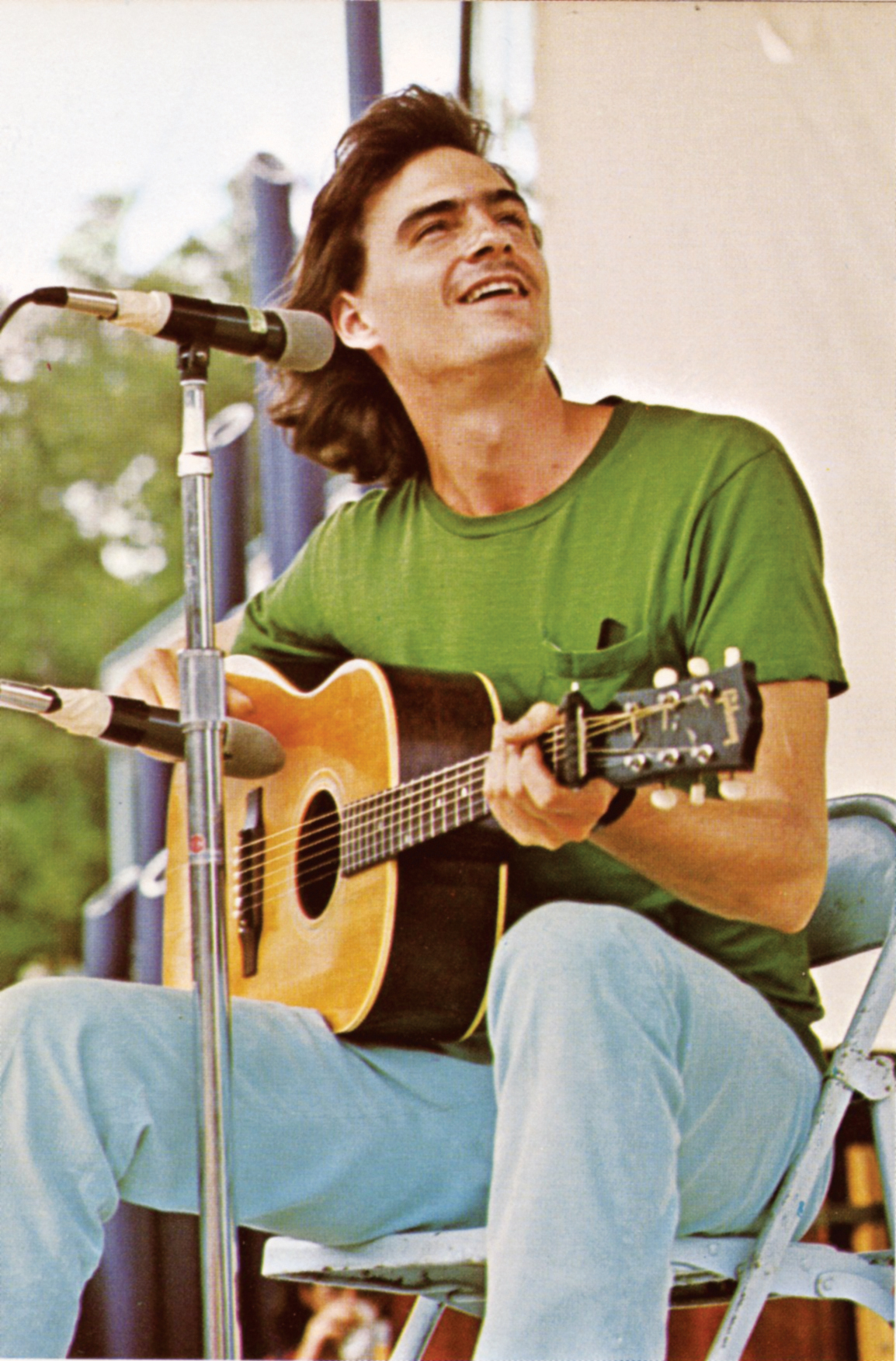

By the time Haber graduated, Jubilee felt so perfect that a then-emerging James Taylor came out to sing Sunshine Sunshine on a dreary day and the drizzle ceased falling. “One of my great memories of Jubilee is everybody’s in such a good mood,” said Jeanne Finan ’71. “In my mind, it was always just a really beautiful, sunny day.”

But of course, just like in 1963, some problems were swirling, namely that the show had grown so big — with as many as 30,000 attending on a single day — that Boy Scouts were brought in to collect the trash off Kenan’s grass and the athletics department had had enough.

(1968 Yackety Yack)

Rock ’n’ roll

The band bookings were hotly debated on campus, but the level of artists the Union brought were remarkable by any standard. They weren’t going to get the Stones or Beatles, and they swung and missed on the Grateful Dead and Santana due to their price tags. But considering the budget from student fees, the fact that free admission meant no gate revenues, that the shows had to be on the weekend and that most performances were only an hour, the lineups the last few years were spectacular:

Joe Cocker, the spring after his virtuoso Woodstock performance; Chuck Berry; Spanky and Our Gang; B.B. King; The Chambers Brothers; Elizabeth Cotten; Sweetwater; J. Geils Band (then an in-your-face blues band); Grand Funk Railroad; Blood, Sweat & Tears; Muddy Waters; James Taylor; and the Allman Brothers Band.

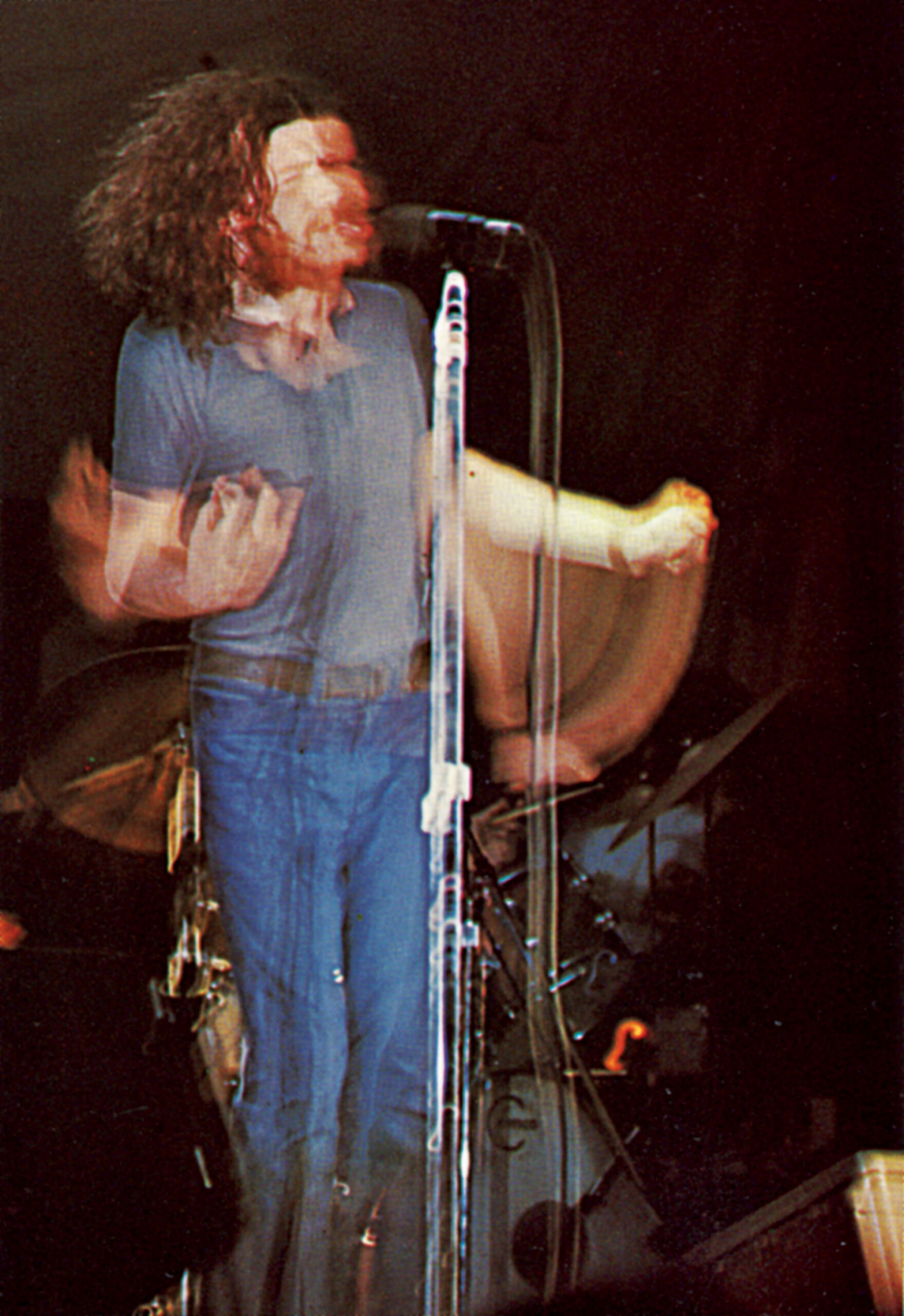

Mad-dog Englishman Joe Cocker, hometown boy James Taylor and Michigan’s Grand Funk Railroad shared Jubilee’s stage in 1970. (Yackety Yack)

Finan was in a local jug band that played at the 1970 Jubilee between big acts. “I look at the list from that year,” she said, “I’m like, ‘How did we get to hear all these people? This is pretty amazing.’ ”

Cocker’s performance, which was part of his whirlwind tour with a band he threw together and called Mad Dogs and Englishmen that resulted in a live album and concert movie by the same title, left a strong impression on many Jubilee attendees. “He is such an iconic performer,” said Fay Hauser-Price ’71, known as Fay Hauser as a Hollywood actor. “To see him on stage there, very close, was really cool. I was somewhat of a hippie in those days, so I was enjoying it a whole lot.”

Hauser-Price was among the 2 percent of Black undergraduates then. She was active in the Campus Y, bringing political speakers to town to “enlighten the whites,” as The DTH put it.

1969: A Connecticut-based and self-styled “aeronaut” named Charles MacArthur solicited Jubilee organizer John Haber ’71 thusly: “A balloon ascension at Chapel Hill will be a matter of discussion at the 50th reunion of the Class of 1970, I can guarantee that much, and should it not be so you have my permission to exhume this old body and desecrate the remains.” MacArthur got the gig and reportedly crash-landed into University Lake.

“I even had a rhythm class, dance classes, to teach people how to clap on the two and the four.” Did her lessons bear fruit at Jubilee? “Yeah, some people picked it up.”

The 1970 Jubilee was getting noise complaints. It also took place amid tremendous national turmoil as tensions and protests rose on college campuses against the bombing of Cambodia. Some unfurled a banner at Jubilee to organize for a student strike.

Grand Funk Railroad concluded the weekend with a show loud enough to be heard across state lines. The next day, the Ohio National Guard killed four protesting students at Kent State and wounded nine more. At UNC, the ROTC building was the target of arson.

Alcohol was always a part of Jubilee, then marijuana gained popularity and so did much more. In reporting this story, this writer was told, unsolicited, tales of acid and mescaline use, for example.

“Drug use was rampant,” said Rich Leonard ’71, Union president for the last Jubilee who also earned his master’s in education in 1973. Scott Moyer ’71 was hired to play drums with Chuck Berry at the final Jubilee. He recalls talking in the backstage tent with the Allman Brothers Band before his gig. “There they are with this huge, I mean enormous, bag of cocaine,” Moyer said. The film made about that Jubilee — titled simply Jubilee 1971; (see video at end of story) — opens with audio of the Allman Brothers’ soundcheck: “Hope y’all as high as we are.”

Jubilee upgraded to Kenan Stadium in 1969. Then came carnival rides, the hot air balloon, pie throwing, a hog caller, a hollering champion, slip-and-slide and an elephant named Sabu.

Alcohol wasn’t sold at Jubilee, but as long as it wasn’t in glass containers, festival goers generally could bring in any beverage they chose. Folks carried in five-gallon gasoline jugs filled with liquor, pony kegs, the works. In the film, people are proudly smoking joints on camera. Drugs were so prevalent that a DTH article previewing the 1971 Jubilee spent seven paragraphs on the medical tent the Union had organized as an “extension of the emergency room of Memorial Hospital” to handle potential overdose cases, among other things.

As Lewis Black says when asked whether he recalls ever seeing an elephant at Jubilee, “I could’ve seen one and one wasn’t there.”

Grand finale

At the conclusion of the 1971 Jubilee on Navy Field, the head of campus security, Arthur Beaumont, sent a memo to UNC administrators assessing the weekend’s events.

“Because of past performances, this does attract a great number of undesirable non-student hippie-type individuals,” he wrote. “They swarmed onto campus in van type buses, old school buses and other vehicles, which they lived in or camped in tents and sleeping bags under our trees.”

The noise complaints continued, tying up phone lines as residents threatened to sue the chancellor and get the Chapel Hill police chief fired. Leonard said that after the first night, some townspeople secured a temporary injunction stating that if the music didn’t cease at midnight on Saturday, he and Henry would be jailed. “Try telling the Allman Brothers to stop,” Leonard said.

Just before the Allman Brothers began to play, one mischievous person was caught before he could untie the canopy hanging over the stage. One night, bales of straw and some of the 3,600 pounds of foam rubber from a jumping pit became kindling for bonfires. Beaumont wrote that when Navy Field’s lights were flipped on at 2 a.m., a “few left reluctantly or had to be helped by their cohorts but most of the drifters just went into our wooded areas like stray dogs and bedded down for the night.”

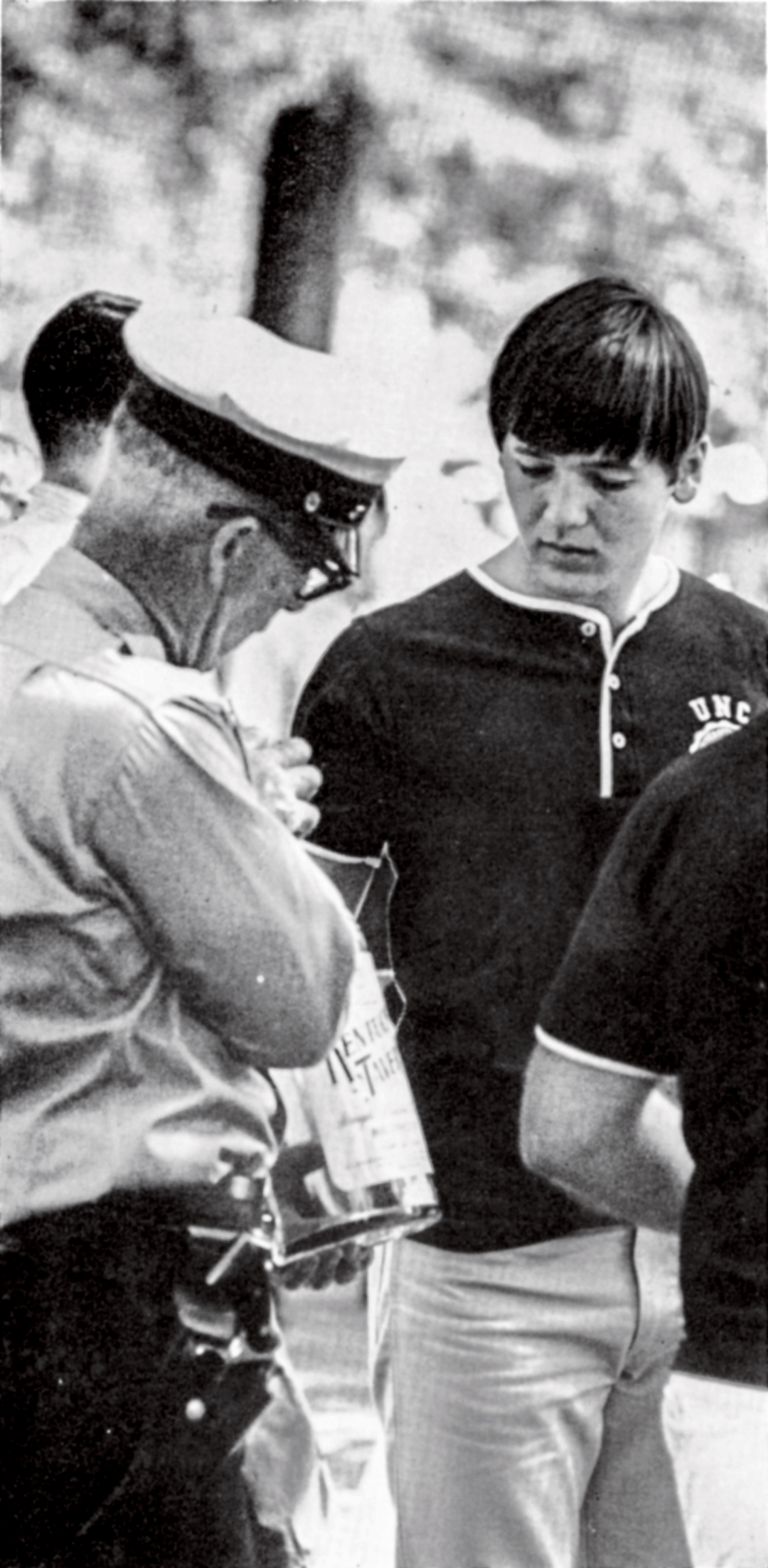

Jubilee had begun with an ethos of openness, but its founders surely never dreamed it’d get so big that festival flyers would hang in head shops up and down the East Coast. Controlling admission necessarily took center stage for the planners. Each student could pick up two tickets (one for a nonstudent guest). But at Kenan, controlling the gates had been easier. When the football team decided the festival was too damaging to the grass and feared player injury from broken glass or can pop tops left behind, Jubilee was pushed to a less secure Navy Field.

The Union hired Pinkerton security guards to work the gate, but just as at Woodstock in 1969, the chain-link fence proved powerless against the forces of those days. Unticketed festivalgoers cut through the fencing and sneaked in, and eventually the gate was crashed. Tom Schnabel ’72, photo editor for the Yackety Yack, appeared in a DTH photograph escaping the stampede along with a guard.

Jubilee 1971 brought 23,000 people to Navy Field. (Yackety Yack)

“That Jubilee was very, very happy,” Schnabel said. “A lot of happy kids. But 23,000 on Navy Field, can you imagine that?” In the rush, the guard was trampled and tore several hand ligaments, according to what Leonard told The DTH at the time.

Leonard said he “felt like that whole weekend it was just borderline out of control. I left the weekend just happy that nothing worse happened.”

The athletics department made it clear Jubilee was unlikely to be welcome on any of those fields again. In addition to running out of venues, the booming concert circuit was starting to make it difficult for college venues to afford major artists, and Union leaders no longer could justify spending such a huge chunk of student fees on an event that in some ways had been commandeered by nonstudents.

Within a week of the 1971 Jubilee, the Union board unanimously recommended that the festival end. Leonard says the board was “shellshocked” by all that occurred at the festival, and he told Henry the move to kill Jubilee needed to be made before the incoming president, Patrizia, was saddled with the burden. “This needs to be on me,” Leonard told Henry. Leonard delivered the unsurprising news to Chancellor J. Carlyle Sitterson ’31, who was not disappointed.

Noise complaints in 1971 tied up phone lines as town residents threatened to sue the chancellor and get the Chapel Hill police chief fired.

Although no final, official decision was made, by the fall semester, Jubilee’s demise was such a foregone conclusion that Patrizia recalled there was no formal announcement or board vote. No DTH story marked a decision point. The Union simply released the entertainment schedule, sans Jubilee. Union board members fielded plenty of gripes, but people largely understood.

“It was a wonderful event,” Patrizia said. “In the circumstances of the time, for all kinds of reasons — what was going on with bands, what was going on in society, what was going on on campus — we just couldn’t make it work for another year. It was a great run.”

Said Leonard, “Our natural idealism got tested.”

A film, an education

The summer before the last Jubilee, a group of creative friends, mainly from the RTVMP department, drove to a theater in Greensboro each Friday night to see Woodstock, the Michael Wadleigh/Martin Scorsese 1970 documentary. Like youth across the country, they were mesmerized to experience in some way the epochal festival they’d missed in person.

Charlie Huntley ’71 was among them, and they were later commissioned by the Union to make the film about what would turn out to be the last Jubilee. Huntley was inspired by Woodstock, by the way it let viewers feel as though they were at the concert, by the creative visual effects, by how it illuminated the culture of their time.

Charlie Huntley ’71 was part of a group commissioned by the Union to make the film about what would turn out to be the last Jubilee.

But the large Woodstock crew had more than a dozen cameras, a Hollywood studio’s financial backing, and 50 miles of film that captured 120 hours of footage. Huntley’s crew had enough money to cover film developing, borrowed equipment and so little film stock they had to plan precisely when to roll the camera each time. Every frame was used in their 26-minute film.

Many of the bands wouldn’t allow them to plug into the soundboard, so they had to put a microphone in front of a speaker instead. Some wouldn’t give permission to synch audio with video. Undeterred, the group still replicated the feel of Woodstock, and Huntley hatched an inventive camera trick to create a split-screen effect.

The learning experience proved to be a step on the way to bigger careers. Huntley went on to win four primetime Emmys as a cameraman. He’s shot just about every major entertainment event there is, including the groundbreaking MTV Unplugged sessions and Paul McCartney at the Ed Sullivan Theater after the Beatles’ performance there had inspired him to become a cameraman in the first place.

Other producers and camera operators in Huntley’s group also went on to distinguished careers — Jim Bramlett ’68, Rick Gibbs ’71, H.B. Hough ’71, Bill Hatch ’71 and Rod Waldorf ’71 — including with worldwide news organizations.

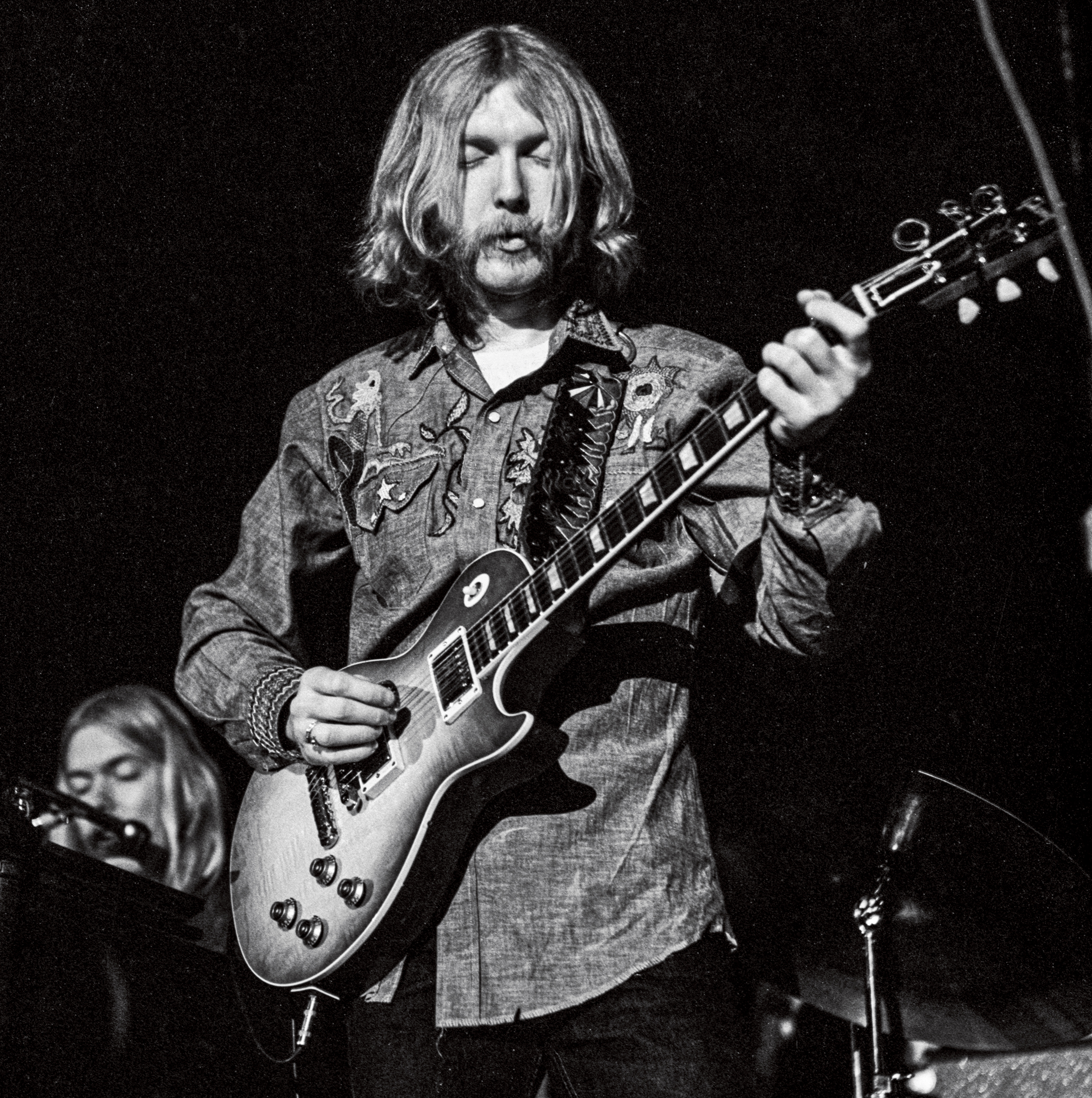

A student-made documentary, titled simply Jubilee 1971, is one of the last times Duane Allman was filmed playing live. (Ric Carter/Alamy Stock Photo)

The Union presidents who put together those Jubilees also credit, in part, their later successes with the responsibilities they were given at such a young age.

“I left Carolina really being comfortable being in charge of big things and also understanding the pitfalls and perils that come with that,” said Leonard, now the dean of Campbell University’s law school; he also is former chair of the GAA Board of Directors. Patrizia, a senior partner in an international law firm, agrees. “It truly was an educational experience. Sometimes you felt like it was an education under fire.”

Haber has enjoyed a long career as an event planner on Broadway, and his love for baking continued after that 100-foot loaf — he owned a bakery and still owns a company that makes specialty cookies in the shapes of Broadway show characters and logos. He also started a theater company in North Carolina after college, a nonprofit to help him avoid Vietnam. Hauser-Price credits the repertory company being unionized with helping her get auditions when she moved to New York and embarked on an acting, producing and directing career that’s still going strong.

Moyer, who played with Chuck Berry, is still a professional musician and music teacher in Los Angeles, mingling with stars as he did in that backstage tent.

At the end of the Jubilee 1971 film, Chuck Berry bid adieu to the crowd: “Yeah, that sounds like Chapel Hill now, yes. You must be really groovy around here after the sun goes down.”

Moyer said that, off camera, Berry then walked down the stairs, climbed straight into his Cadillac parked by the stage and rode off. The film continues briefly, with footage of two police officers surveying the empty field, their hands in their pockets, strolling amid all the garbage left behind. Union records show it took a team — likely made up of predominately Black workers —195 staff hours at as little as $1.76 per hour to clean up. The athletics department sent the Union a bill.

The film’s final scene could be interpreted differently by different beholders, especially in hindsight. It could be an homage to the closing minutes of Woodstock. It could signify that youth had triumphed over authority. What did the filmmaker intend?

“I wanted to show it because we’re hippies and we’re saving the world,” Huntley said, “but we’re still pigs.”

Mike Ogle ’02 is a freelance writer based in Chapel Hill. He maintains a newsletter, Stone Walls, about under-told local history.

Lewis Black ’70 Survived Jubilee’s Swan Song

Within minutes, comedian Lewis Black ’70 replied yes to an email asking whether he had any recollections of Jubilee he’d be willing to share. He wrote that his memories from the last two Jubilee music festivals at Carolina, in 1970 and ’71, were “indelible.” When I called him at his New York apartment, he talked for 45 minutes, his enthusiasm for Jubilee 50 years on still clear.

He spoke in the perpetually irritated manner we’ve come to know on the screen and stage, if just a notch lower, and still full of profanities. He ranted mostly in praise and with joy rather than in his signature kvetching. Despite a memory that’s been scrambled, he says, by decades of touring, he still has vivid memories of Jubilee.

Lewis Black ’70 still has vivid memories of Jubilee: “The problem is it’s all drug stories.” (Wikimedia Commons/Jason D. Smith ’94)

“The problem is it’s all drug stories,” Black said. I told him it’d be up to the magazine’s editors if they’d get printed. He called them “idiots” and said to tell them: “They all did them, too!” And he was off. He remembered quite a lot about the music, using “unbelievable” repeatedly to describe the shows that tens of thousands got to see on campus.

“You’ve got Grand Funk Railroad at the height of what would be their fame,” he says as he starts rattling off the musical artists, moving next to Joe Cocker. “That was the Mad Dogs and Englishmen tour, which is huge. Huge. They did 31 shows. We were one of the first. I think it’s actually in the documentary about it.” He named some of the musicians assembled for that tour. “He’s got essentially something that’s never occurred, this all-star group, massive group that toured together.”

Black recalls Rita Coolidge being announced to come up and sing. “I didn’t know who she was, and she comes up and sings this song, and you go, ‘Are you kidding me?’ Because you’re going to see Joe Cocker, and he’s got 10 people that are just as powerful as he is.”

Black saw the New Deal String Band, who had “just kind of hit”; Sweetwater at “their moment in time”; B.B. King, a “legend” by then; J. Geils Band, “right at the top of their game”; Muddy Waters; Tom Rush; Spirit (one of Black’s friends hallucinated that the guitarist “might fly away with bat wings”); Chuck Berry, “for f—’s sake”; and James Taylor “in the f—ing moment in time when he’s hitting it and he’s from there so that just sends it out the window. And we’re on drugs! So, it’s mythic.”

Black says when he saw 1970’s musical lineup, he told friends at colleges all over the country to come. “Get here,” he said. “You’re not going to believe what’s going on here.”

The stories pour out. He shares them with wonder, and he chuckles as one does when youthful memories spin to the top. Trying to make pot brownies for the first time, but no brownie mix could be found as Jubilee approached. “It was like toilet paper” during the pandemic, Black says. Chocolate pudding was gone, too, so he settled on vanilla. But he didn’t know how to correctly add the special ingredient. “I didn’t think to chop the stuff up,” he says. “So I just dumped it all in this pudding, and it was horrifying.”

When Black saw the 1970 lineup, he told friends at colleges all over the country to come. “Get here,” he said. “You’re not going to believe what’s going on here.”

Black’s crew all ate the pudding concoction anyway and headed for Kenan Stadium. Trying to get there, their Volvo’s wheels got stuck over a ditch and were spinning, not making contact with the ground. “We thought we were driving,” he says, but after a couple of minutes one of their dates said: “You know you’re not going anywhere.” Black says, “We had no clue,” and they decided it was best to walk the rest of the way to Jubilee.

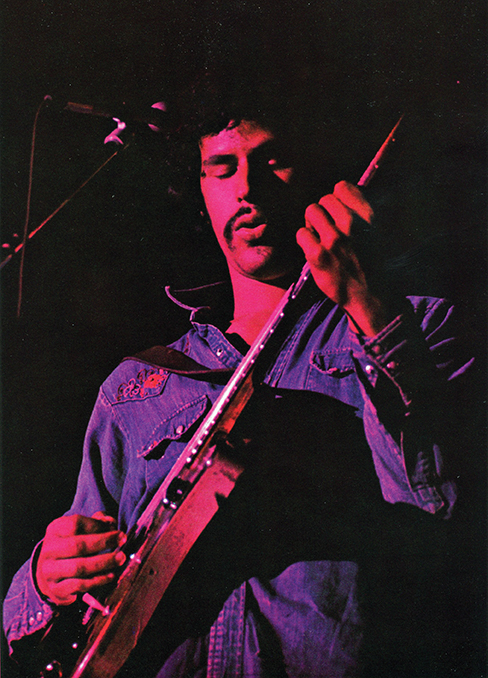

1971: Randy California of the band Spirit. Black said one of his friends hallucinated that California “was going to fly away with bat wings.” (Yackety Yack)

Black graduated that spring, but a playwriting fellowship kept him in town doing graduate coursework. His resulting play, Feast, about growing up in the 1950s, toured around North Carolina and received a rave review in The Daily Tar Heel, but his professor gave him a B. “The play had just been in seven different cities in the state, but I’ll give you a B,” he says, his eye roll felt over the phone.

Many of Black’s memories from that next, and last, Jubilee are around the Allman Brothers Band’s show. Its members were in the headlines at the time over drugs, and Duane Allman died in a motorcycle accident about six months after Jubilee. “That’s a classic concert,” Black says. “It’s one of those ones that for years you’d go, ‘I saw them all together.’ ”

Black and his friends were about 25 yards from the stage and could see so well that one pointed at Duane Allman because he’d noticed he was replacing a broken string while still playing his guitar. “He was futzing around with it, but he kept music coming out of that while he was replacing the string, which was kind of astonishing,” Black says. “Really good seats.”

The band members were in trouble with the law at the time, having been busted a few weeks prior with a number of drugs. Black recalls that they explained to the crowd that they had a curfew due to pending legal matters.

“We were going nuts, wanting another encore, and they go, ‘We’d love to, but if we don’t get back, we go to jail,’ ” Black says. “It was kind of, wow, which added a whole other level. Made it really: ‘This is the hippest concert I’ve ever been to! They can’t even stay because they’ve got problems with a heroin charge. Woohoo!’ ”

— Mike Ogle ’02

During the GAA’s 2011 Spring Reunions, members of the Class of ’66 and ’71 held a panel discussion to discuss their memories of Jubliee. Recorded May 7, 2011.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.