Long Odds, Long Hours

Amir Barzin ’06 and other Carolina health experts were handed the seemingly impossible job of containing the coronavirus on campus. Here’s how they did it.

by Janine Latus

It was February 2020, and infectious disease experts at Carolina were watching COVID roll in like a storm coming off the ocean. Their contacts around the world were sending warnings. David Wohl, a professor in the division of infectious diseases at the UNC School of Medicine and renowned for responding to Ebola and Lassa fever in Africa and HIV in the United States, started sounding the alarm.

The state’s first case was diagnosed on Feb. 28, and students left for spring break a week later. While students were away, the University announced on March 11 that it was extending the break by a week, after which remote instruction would begin. The administration strongly urged students who could take classes remotely to do so.

David Wohl. Photo: UNC

Three days after the University’s announcement, on March 14, Wohl took a call from Ian Buchanan ’04 (MD), ’06 (MPH), deputy chief operating officer for UNC Health. Buchanan asked him how long it would take to set up a testing center at the University. “With enough money and enough resources, I could do it in two days,” Wohl recalled saying. “And they were like, ‘Do it.’ ”

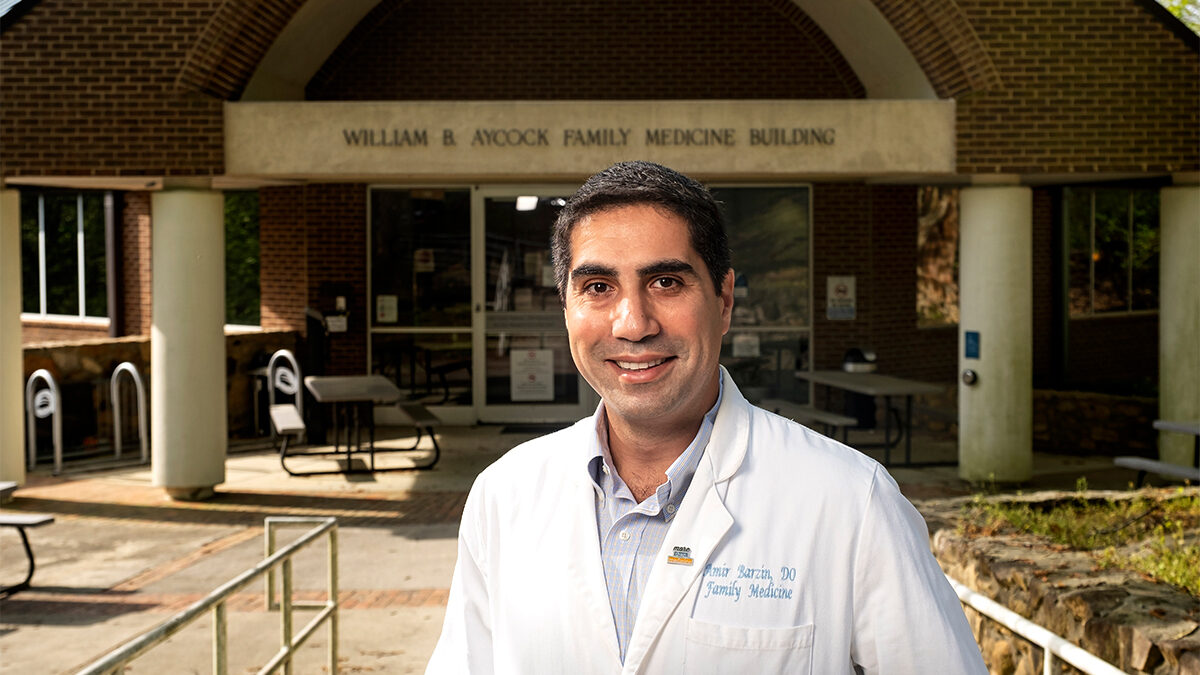

That day, Wohl met Amir Barzin ’06 in the parking lot of UNC’s largest outpatient practice, the Ambulatory Care Center on Mason Farm Road on the southwest part of campus. The University had asked the two to meet. Wohl was tapped for his infectious disease expertise; Barzin, an osteopath who was director of the Family Medicine Center and UNC Health’s Clinical Contact Center, a 24-hour hot line, was tapped for his skill with operations. It was the first time Wohl and Barzin met. The two quickly agreed the parking lot could be turned into an outdoor facility to collect test samples. Together they devised a system that would allow traffic to flow efficiently, without people congregating or doubling back and passing by — and maybe infecting — other individuals.

Creating a testing site, Wohl said, was like building a moat that would protect the hospital from an influx of infected students. He and Barzin set up tents and orange cones and created lanes for students and work spaces for medical staff. By March 16, within the two-day time frame Wohl promised, the Respiratory Diagnostic Center testing site opened in the parking lot.

It was early in the effort to deal with COVID. No one knew, of course, the frenzy would last two years and require the best efforts of nearly everyone at UNC. At the moment, Barzin didn’t know he would become one of the institution’s leaders to contain the coronavirus, eventually being named director of what would become the Carolina Together program, the University’s coronavirus response team charged with keeping the campus community safe.

In the months to follow, he would spend his days and nights wondering whether he was up to the task of containing the highly contagious virus, whether he was pushing people too hard, and whether, as colleagues warned him, failure would most likely jeopardize his career. As students returned to campus this August, cases of infections in Orange County were still being reported but had been relatively flat for weeks. The mood is decidedly different. Much of what the University now knows about how to combat the spread of the virus can be traced to the rapid, and at times stressful, response Barzin and the team of health experts organized on the fly two years ago.

“This semester I feel like we’re on really good footing,” Barzin said. “There are a lot of protective measures and treatment options in place that we have never had before.”

That includes easy access to testing, vaccines and treatments. “We’ve also learned a lot more about the virus and how it reacts, how it spreads and who’s vulnerable to severe infections, which makes me feel like we’re starting at as good of a point as possible.”

“We were always looking and saying, ‘What’s next? What’s next? Where can we gain efficiencies? What are we not doing well? What do we need to do to make sure that X, Y and Z are improved?’ There were a lot of sleepless nights for sure.” —Amir Barzin ’06. Photo: UNC

“We’re human”

Barzin was familiar with the workings of UNC’s health complex. He spent his four years as an undergraduate at Carolina earning his bachelor’s in biology on a Morehead Scholarship (now Morehead-Cain). He then returned to his home state of Texas for a master’s in biomedical science before attending medical school at the University of North Texas Health Science Center – Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine. Barzin returned to Chapel Hill in 2012 for his residency. He became a chief resident in 2015.

When the Respiratory Diagnostic Center testing site opened, Barzin spent part of his days in the parking lot leaning through car windows, his face covered in an N95 mask and his surgical scrubs flapping in the wind, rolling swabs in drivers’ nostrils before sliding them into tubes, screwing on the tops, dropping them into individual bags and sealing them.

The RDC was one of the first testing sites in the state, and people drove in from the coast and the mountains to get checked. Thousands of samples were sent to the lab of Professor Melissa Miller, director of Carolina’s Clinical Molecular Microbiology Laboratory, which operated three shifts a day to test the samples as quickly as possible. At the time, no one knew exactly how the virus spread or how dangerous it could be, only that a large number of people were dying.

The University’s response involved multitudes of people. Barzin, who was born in Tehran during the Iran-Iraq War and raised in Texas (which explains his ever-present cowboy boots), was picked by then-Provost Bob Blouin to oversee a campuswide effort that involved infectious disease specialists and engineers, transportation workers and housekeepers, electricians, students and IT experts. Amy James Loftis, laboratory manager for Carolina’s Global Clinical Trials Unit, set up a makeshift research clinic next to Barzin’s testing site, where staff drew blood from infected patients to study COVID’s effect on blood clotting. A kidney team donated a dialysis truck that Loftis converted into a small, air-conditioned clinic. The Ambulatory Care Center provided two clinic rooms where she and her team tested potential monoclonal antibody treatments. Barzin constantly asked for everyone’s help, opinions, expertise and willingness to work long hours.

In June 2020, University leaders decided to bring students back for fall semester classes starting Aug. 10, a decision they said was made with input from UNC infectious disease experts, student and faculty advisory groups, public health experts, state and Orange County health departments and the UNC System.

“We thought COVID-19 prevention strategies would be successful,” said Myron “Mike” Cohen, the Yeargan-Bate Eminent Distinguished Professor of medicine, microbiology and immunology and director of the Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases. “But we make mistakes. We’re human.”

Barzin was in the mountains with his wife, Anna Routh Barzin ’07, and his in-laws when he watched Cohen and Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz on 60 Minutes explaining how the University planned to open in the fall.

“I thought, it’s very bold of our University to come forward and be one of the first ones to step into this light,” Barzin recalled. “It’s hard to be the first one to do something, and sometimes when you do it, you could be cast in two different lights. You did it right, good job, good on you. Or, you should have maybe thought about it a little bit differently, done something differently.”

Cohen said a committee of University leaders thought they could create reasonably safe classroom environments, as long as everyone wore masks. But the health community still didn’t fully understand how the virus was becoming more contagious, not less so, Cohen said: “It was evolving to be a bigger enemy.”

UNC’s plan to reduce infections depended on students wearing masks, but students have highly interactive social lives that bring them into close proximity to each other. Starting on the fifth day of classes, alerts about clusters of students testing positive came one after the other: Aug. 14 in Ehringhaus, the next day in Granville Towers and the Sigma Nu house, the next in Hinton James. In one week, cases of COVID spiked from 2.8 percent of tests to 13.6 percent, according to the University’s COVID dashboard.

The University was at risk of running out of isolation spaces. Just two weeks after students began moving onto campus and seven days after classes began, the administration decided, on Aug. 17, to shut down the University and hold classes virtually. Graduate and professional programs were allowed to follow the discretion of school and department leaders. The University had to quickly test students before they left campus to make sure they weren’t carrying an infection back to their home communities.

“The big problem with infectious diseases is you can’t really function until you know the rules,” Cohen said, adding they didn’t know how the virus was transmitted, how efficiently or what it did once it entered the body. “We had no rules, no medications and a new organism,” he said. “We began seeing a lot of hospitalization and death very quickly. We didn’t know until much later that this was going to almost always be a function of age. As it turned out, young people can tolerate this infection without serious morbidity and mortality.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, only 0.1 percent of COVID-infected people under the age of 25 died. At UNC, students have avoided severe disease, Barzin said.

“It’s going to be hard, but it’s not not doable.” —Amy Loftis. Photo: UNC

Another go at it

In October 2020, just as infections were rapidly accelerating, Blouin asked Barzin to take the lead in ensuring students’ safe return for the 2021 spring semester. Barzin said the people closest to him recommended caution, reminding him of the high-profile nature of the job and telling him he could “either go down in flames” or actually help the situation. “I had enough confidence in the team around us that we would succeed,” Barzin said. “I was fine with taking criticism or responding to questions if it meant we were able to continue to move the ball forward.”

Barzin was asked to do the job before a vaccine was available, and University leadership decided it was prudent to create an on-site lab to collect swabs and test them for COVID. Sending swabs out cost up to $100 each, and results took about three days to come in, which meant infected students would have interacted with dozens of other people before they knew they were contagious. By contrast, on-site testing could significantly reduce costs and yield results in a day. “That’s when we kicked into high gear,” Barzin said.

Because he hadn’t worked in a lab handling hazardous materials since high school, Barzin partnered with Loftis, who had set up labs worldwide to test for deadly diseases such as Ebola, even in places with unreliable electricity.

Illustration: Haley Hodges ’19

Cohen called Loftis’ mentor, Susan Fiscus, a former Carolina professor of microbiology and immunology, who knew how to design a lab to meet federal standards for safety and accuracy, and begged her to come out of retirement. Fiscus agreed, Cohen said, on the grounds that Loftis work with her. Fiscus was worried about the timeline, but Loftis assured her she’d done more with less. “We have electricity. We have a power grid that works, right?” Loftis recalled saying. “It’s going to be hard, but it’s not not doable.”

For weeks, Loftis and Barzin worked 12- to 18-hour days, skipping meals, negotiating with supply companies, performing their real jobs — Barzin still saw patients and served as medical director of the Family Medicine Center, and Loftis continued her research — and caring for their families on the side. They found 2,000 square feet of lab space in the Genome Sciences Building, near Kenan Memorial Stadium. Loftis went in with a tape measure and colored tape to mark where machines and file cabinets would go. She changed plans when a stressed supply chain meant she could buy only a 5-foot cabinet for a spot that would hold a 4-footer. She turned a former hallway off the lab space into a Biosafety Level 3 lab.

They gathered the components of each test kit — biohazard bags, little packets of desiccant to absorb spilled samples, test tubes and swabs — to check for problems in the process. Would the swabs prevent the tubes from closing? Would the caps be easy to twist on and off given the staff would handle possibly thousands of samples daily? Would tweezers used to remove the swabs be small enough to fit into the tube but big enough for a good grip?

Simultaneously, Barzin and Loftis worked on architectural drawings and coordinated the team that installed the lab’s electrical system and air conditioning. They were on numerous calls with Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. representatives, trying to expedite installation of the company’s Amplitude Solution device, a fast throughput processing machine that performs diagnostic lab tests. They worked with vendors, navigated the University’s procurement process and constantly asked about the most cost-effective and fastest way to get what they needed.

“Amy’s the genius behind the lab,” Barzin said. “She looked at everything, saying, ‘Here’s what we need in terms of humans, machines, tests.’ ”

Still, with the 2021 spring semester just a little more than two months away, the team didn’t have the equipment they needed. Barzin was worried.

“There were many, many points during that time where it felt like, am I doing the right thing?” he said. “Are we ordering the right equipment? Is this going to be installed the way that people said it is? Anytime you take on a project in your home, they say, ‘Oh, we’ll have it done in two months,’ but two months can become four months very quickly.”

They had eight weeks to get everything running. Barzin ordered 300,000 labels and 300,000 test tubes. But the whole world was competing for supplies. At one point, a freezer Loftis thought she’d ordered was no longer available because someone in the state of Georgia hit the buy button a second before she did. The global market for scientific equipment was overwhelmed.

“The big problem with infectious diseases is you can’t really function until you know the rules,” Mike Cohen said, adding they didn’t know how the virus was transmitted, how efficiently or what it did once it entered the body. “We had no rules, no medications and a new organism.” Photo: UNC

Progress

In November, about two weeks before Thanksgiving, three truckloads of equipment backed up to the loading dock at the Genome Sciences Building. The Amplitude machine arrived the next week, and the following week Thermo Fisher crews began assembling it. Days before Christmas, the machine passed quality checks.

Barzin and his team also set up testing sites. He had had enough of heat, wind and thunderstorms in parking lot tents, he said, so he coordinated with UNC’s facilities management to set up indoor sites that made it easy for students to cycle through. He worked with the Carolina COVID Student Service Corps, a group of about 1,000 student volunteers who assembled test kits and served as testing-site guides.

Each specimen required a traceable chain of custody, so he called the University’s Transportation and Parking division, which designed a traffic flow for cars and provided a vehicle to transport the samples.

He worked with information-technology experts and the Hussman School of Journalism and Media to create HallPass, an app that allowed students, staff and faculty to move through the testing process quickly and confidentially.

In all, about 50 people worked to process a day’s worth of samples.

Barzin and Loftis were frequently on the phone with other universities, as well as the CDC and the Food and Drug Administration, to discuss the latest news and research about the virus, which was changing by the day. They sometimes met three times a week with University administrators to explain what they knew.

Illustration: Haley Hodges ’19

Most days Barzin and Loftis arrived at the lab at 6 a.m. and didn’t leave until 2 the next morning. Barzin had a 2-year-old daughter, Ruth, at home and a baby on the way. (Jack was born in June 2021.) “I felt, ‘Gosh, I’m not upholding my obligation of being a good father and a good husband and not carrying my share of the load,’ ” he said.

Barzin asked his wife whether he was in over his head. “You do what you have to do, but it has to stop at some point,” he recalled her answering.

As expected, Anna had confidence her husband would have the lab up in time to test samples on site. “Amir is a problem solver,” Anna said. “He loves building things from the ground up … and it mattered because he’s making a difference in this horrible thing everyone is experiencing.”

Still, Barzin continued questioning himself. Are we doing the right thing? Are we working our staff too much? Are people feeling burnt out? Am I a contributing factor in that burnout? “It makes me think, at what point is that human toll just too much?” he said.

There were also moments of welcome relief. Barzin remembers one day when Ollie, a little silver robot that moved samples within the Amplitude, was reading the barcodes on the tubes that identified the samples. Results had been showing up properly. And then Ollie stopped.

Loftis spent days bent over a lab table, hand scanning labels that Ollie couldn’t read, while Barzin tried to figure out whether new labels would fix the issue. Then a shipment of higher quality bar codes arrived. The team affixed the new ones on the samples, and Ollie perked back up.

Barzin said fear is what drove him at times. He and Loftis constantly developed contingency plans in case something went wrong. He’d wake up at night, he said, and obsess over whether they should have done something differently. He’d read an article in The Daily Tar Heel criticizing some aspect of the University’s response and contact the author to ask what they could have done better.

“We were always looking and saying, ‘What’s next? Where can we gain efficiencies? What are we not doing well? What do we need to do to make sure that X, Y and Z are improved?’ ” Barzin said. “There were a lot of sleepless nights for sure.”

Sometimes when you’re the first to do something, “you could be cast in two different lights. You did it right, good job, good on you. Or, you should have maybe thought about it a little bit differently, done something differently.”

—Amir Barzin ’06

A different landscape

In January 2021, the University brought back 1,500 students to live in dorms on campus to assess how the new system worked. The students were tested the first week they returned, with a 0.6 percent positive rate. Infected students were put in isolation. The goal was to keep infections as low as possible so the need for housing for isolated students didn’t exceed capacity or overwhelm the hospital system. It worked. The percentage of positive tests for students and University employees dropped from 0.9 percent in January 2021 to 0.2 percent in April 2021, according to the dashboard. None of the students who were infected were sick enough to be hospitalized, Barzin said.

During the summer of 2021, vaccines became available, and the University allowed more people on campus. The combination of vaccines and testing kept infections low, and things were looking bright for the fall semester, even though the Delta variant was dominant and infections were increasing again, making the testing program even more important.

When the Omicron variant surged in December, the University pivoted again, asking students to self-quarantine rather than sequester in a dorm. Positive tests increased this past January to 14.3 percent along with a national spike, and then the rate on campus dropped in the ensuing months, according to the Carolina dashboard. As at-home testing became available, Barzin’s team closed all but one testing site, with slots available by appointment only, so the number of administered tests remained small enough for the lab to provide results within a day.

Looking back, Barzin said he found inspiration in how so many people on campus came together to make the community as safe as it could be. “This is definitely a moment to shine,” he said. “If you are looking for the Carolina spirit, here it is.”

Blouin said Barzin’s willingness to encourage and respect other people’s expertise — from virologists to truck drivers to infectious disease specialists to housekeepers — made UNC’s coronavirus response successful. “None of what we did was easy, but what made it easier was the way Amir communicates and the way people are comfortable and trusting of him,” he said.

Barzin never strayed from the science, Blouin added, which sometimes made him unpopular because he had early access to data the public didn’t. Barzin put himself in front of faculty and the public and took time to answer questions, he said, and Barzin communicated the science in a way everyone could understand, so people didn’t feel as if they were being asked to do something without a clear explanation. “Even if people disagreed, they could not question the level of transparency that Amir brought to the process,” Blouin said.

Through it all, Barzin leaned on his training as an osteopath to look at things holistically. “For me it’s always big picture, the whole body,” he says. “This is the same thing.”

In August, as students settled into their dorms and classes, Barzin and other health experts felt they were prepared thanks to the work they accomplished over the past two years. The University encourages students and faculty to wear masks in buildings, especially given the latest coronavirus variants identified this year, but Barzin said the situation on campus feels much more under control now.

“The downstream effects on the hospital are so far small,” Barzin said. “We’re armed with more information in terms of what is the true risk and what helps prevent severe disease. This is a way different landscape than in the past few years.”

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.