Officials Resolve to Find “Lawful, Lasting” Plan for Silent Sam

Posted on Aug. 28, 2018 | Updated Sept. 5, 2018

The 9-foot marble base in McCorkle Place remains empty after the Confederate monument Silent Sam was toppled by protestors. (Photo by Grant Halverson ’93)

Following two simultaneous, hourslong meetings of UNC’s Board of Trustees and the UNC System Board of Governors on Aug. 28, members of the two governing bodies passed resolutions aiming to resolve issues and ensure public safety over Silent Sam, the Confederate monument, which has been a lightning rod for the campus dialogue about race in recent years.

The actions came a week after the monument was pulled off its pedestal by organized protesters.

At the outset of the trustees’ meeting, Chancellor Carol L. Folt reflected on a week of high emotion. As students returned to campus, the events surrounding the Confederate monument brought about “intense emotions,” she said, noting “the pain, the frustration and anger that’s being felt.”

She added: The “nation’s eyes are upon us.”

Key language in the boards’ resolutions addressed the goal to ensure a “lawful and lasting” plan to preserve the monument with attention to safety. The Board of Governors’ resolution (PDF), which preceded the trustees’ action by about an hour, directs the chancellor and trustees to devise such a plan and submit it to the system board by Nov. 15.

The trustees resolved (PDF) that the board will respect and enforce the law, do everything possible to ensure a safe campus, honor values of civil discourse and “educate and curate our monuments and our history with integrity.”

The chancellor said she and the board would consider all options for placing the monument on campus in a place of prominence, while ensuring public safety and the preservation of the monument and history. Three days later, she elaborated in a message that began “Dear Carolina Community:” In it, the chancellor spoke of “an opportunity that has opened for us … to identify a safe, legal and alternative location for Silent Sam.”

She noted: “Silent Sam has a place in our history and on our campus where its history can be taught, but not at the front door of a safe, welcoming, proudly public research university. We want to provide opportunities for our students and the broader community to reflect upon and learn from that history. Wide consultation, and lots of listening on campus and beyond, are necessary if we are to move toward peace and healing. The plan they have asked us to prepare will be ready for presentation to President Spellings and the Board of Governors in November as they specified. We will be sharing details on a planning process with you as soon as we possibly can.”

The University’s libraries are trying to take themselves out of contention for the possible relocation of the statue. The Administrative Board of the Library issued a statement on Sept. 4 that read in part: “In accordance with UNC’s Policy on Prohibited Discrimination, Harassment and Related Misconduct, the Libraries are ‘committed to providing a safe, diverse, and equitable environment to all members of the Carolina community.’ Relocating this statue into one of UNC’s libraries would inhibit their fundamental mission of ‘research, teaching, learning, and public service for the campus community, state, nation, and world’ and create an unsafe and untenable environment for our students and staff.

“Librarians and archivists across the nation are at the forefront of the preservation of the First Amendment, yet they do so by preserving access to knowledge,” the statement continued. “The presence of this statue in a UNC library at this time would inhibit such access.”

The statement further said that placement in Wilson Library, which houses UNC’s special collections, could be a fire safety issue. “Wilson Library, for example, does not have sufficient fire protection to handle the increased risk of fire that accompanies the continued protests and counter-protests of the monument.”

The board added a recommendation that Silent Sam “be placed in a location such as the North Carolina Museum of History [in Raleigh] — a place dedicated to the interpretation of history through exhibitions and educational programs, with the presumption that the NCMH has or can be provided with the necessary security resources to house the statue safely.”

The Aug. 28 votes by UNC’s Board of Trustees and the UNC System Board of Governors followed unusual meetings that appeared to have been scheduled to run back-to-back.

The trustees met in closed session for five hours, with an agenda indicating that closed-session time anticipated being devoted to a legal update, for “reports concerning investigations of alleged criminal misconduct” and to discuss “potential action plans to protect public safety.” Media reports indicated the Board of Governors’ members planned to discuss a legal briefing in its closed session.

The statue came down at about 9:15 p.m. on Aug. 20, the day before fall classes started after protesters — who had erected anti-racism banners around it in an action that started at 7 p.m. — worked behind the cover of the banners to attach ropes and pull it down. One witness said it came down in about 10 seconds. The phrase “Do it like Durham” was seen on T-shirts and on a cap that was placed on the statue’s head — a reference to a Confederate soldiers monument that was pulled down by protesters last year.

The next morning, the statue’s empty 9-foot marble base remained.

Protesters covered the felled statue with dirt as smoke bombs were ignited. Campus police formed a perimeter around the monument but did not take physical action to stop what was happening.

Silent Sam lies face down in the dirt after being toppled from its base on the day before fall classes were to start. (Photo by Alex Kormann)

“It was face down in the mud as a late night thunderstorm passed through town,” The News & Observer reported. It was later loaded onto a truck and taken away.

Initially, a single arrest was reported, involving resisting, delaying and obstructing an officer. Video showed several police officers trying to subdue one participant and protesters and others — some wearing what appeared to be gas masks — arguing and shoving in Franklin Street.

Late in the week, three people were charged with misdemeanor riot and defacing of a public monument in warrants filed by UNC Police. Police said those arrested are not UNC students and are not otherwise affiliated with the University. On Aug. 30, it was reported that a total of five people were arrested in connection with the Aug. 20 event, one of whom is a student; she was identified as Margarita Sitterson, a first-year student and a granddaughter of former Chancellor J. Carlyle Sitterson ’31, who was chancellor from 1966 to 1972.

Seven people — none of whom are students or are affiliated with UNC, according to police — were arrested Aug. 25 after a small contingent of people protesting the pulling down of the statue clashed with a much larger group of those supporting the removal. The air on McCorkle Place on a Saturday morning was electric with a large police presence — some of them in riot gear — among the some 200 people. Scuffles broke out between the opposing protesters and between protesters and police.

The arrests were for assault, damage to property and inciting a public disturbance. Two also were charged with resisting arrest; those arrests did not involve students or individuals affiliated with UNC, police said.

According to media reports, as of Aug. 30 a total of 14 individuals were facing charges connected to the first two protests. A third protest that occurred in the evening of Aug. 30 resulted in three additional arrests.

The tearing down of Silent Sam was prominent in the national news all week. “Protesters on Monday night toppled Silent Sam, the prominent Confederate monument whose presence has divided the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s campus for decades,” The Chronicle for Higher Education reported. “After the statue fell, jubilant protesters cheered, chanted and embraced as the police looked on.”

“I watched it groan and shiver and come asunder,” Dwayne Dixon, an assistant professor of Asian studies, told The Daily Tar Heel. “I mean, it feels biblical. It’s thundering and starting to rain. It’s almost like heaven is trying to wash away the soiled contaminated remains.”

Natalia Walker, a freshman from Charlotte, told the paper: “I feel liberated — like I’m a part of something big. It’s literally my fourth day here. This is the biggest thing I’ve ever been a part of in my life, just activist-wise. All of these people coming together for this one sole purpose and actually getting it done was the best part.”

Social media filled up early Aug. 21 with comments from people who decidedly did not agree that the statue should have come down.

Early that morning, the chancellor wrote to the University community: “As you are probably aware, a group from among an estimated crowd of 250 protesters brought down the Confederate Monument on our campus last night.

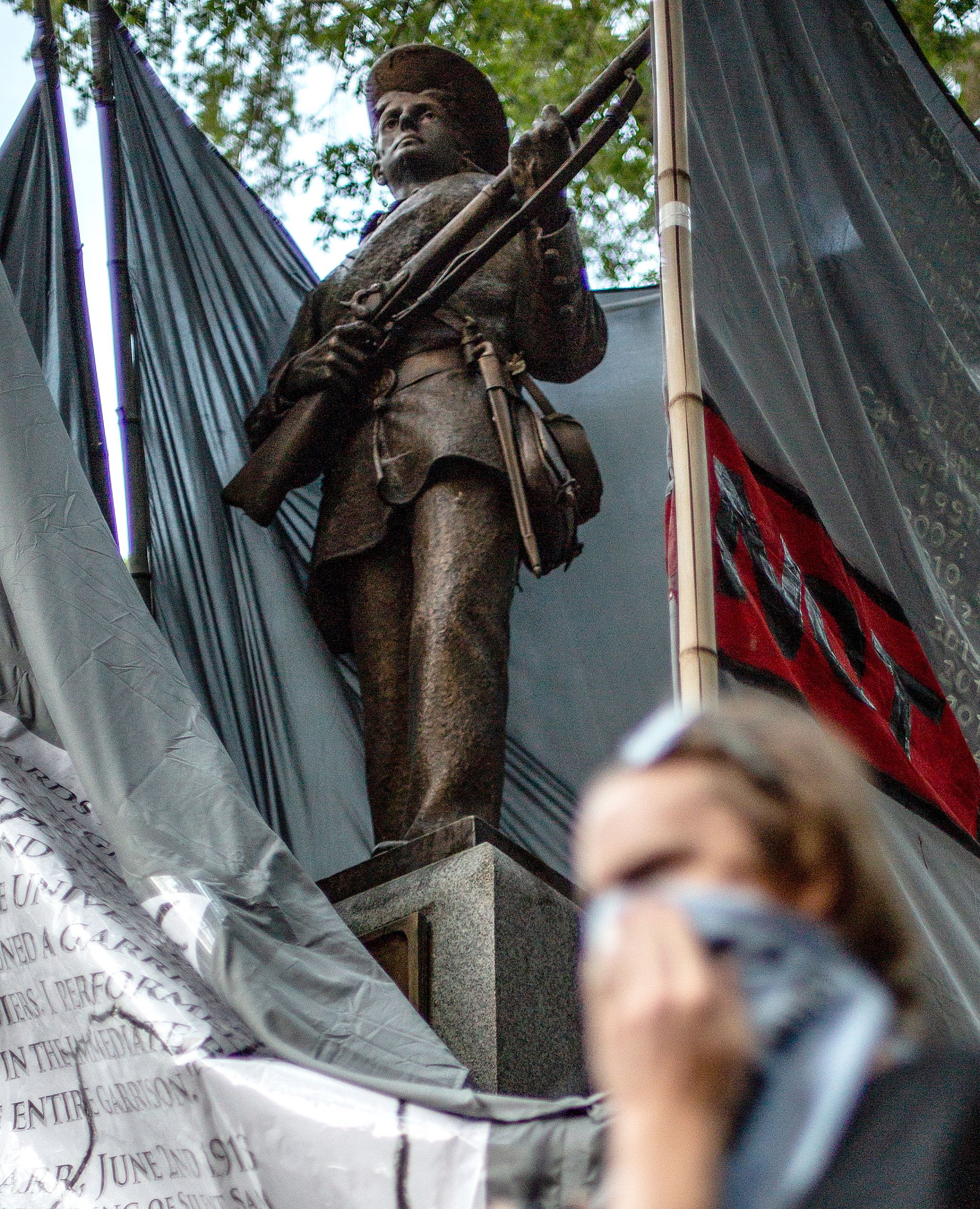

Protesters — who had erected anti-racism banners around the statue in an action that started at 7 p.m. — worked behind the cover of the banners to attach ropes and pull it down. (Photo by Alex Kormann)

“The monument has been divisive for years, and its presence has been a source of frustration for many people not only on our campus but throughout the community.

“However, last night’s actions were unlawful and dangerous, and we are very fortunate that no one was injured. The police are investigating the vandalism and assessing the full extent of the damage.”

The office of Gov. Roy Cooper ’79 (’82 JD) released a statement that said he understood the frustration over the issue, “but violent destruction of public property has no place in our communities.”

On Aug. 25, Folt told a news conference that safety was still her primary concern — “preparing for events and identifying a sustainable solution.”

The Aug. 20 protest started as a demonstration in support of Maya Little, a doctoral student in history and a consistent leader of the protest movement who was arrested in May after she dumped red ink and what she said was her own blood on the monument in full view of the police.

Little was at the Aug. 20 protest and told the crowd: “Right now, we do have a memorial on campus. A memorial to white supremacy and to slave owners. And to people who murdered my ancestors.”

Folt sent a message on Aug. 21 saying the State Bureau of Investigation would be called in. The message also was signed by trustees Chair Haywood Cochrane ’70, UNC System President Margaret Spellings and Harry Smith, chair of the system Board of Governors.

“The safety and security of our students, faculty and staff are paramount. And the actions last evening were unacceptable, dangerous, and incomprehensible,” Spellings and Smith wrote in a separate statement. “We are a nation of laws — and mob rule and the intentional destruction of public property will not be tolerated.”

Tim Moore ’92, speaker of the N.C. House and a past member of the GAA Board of Directors, called for prosecution of those involved.

“There is no place for the destruction of property on our college campuses or in any North Carolina community; the perpetrators should be arrested and prosecuted by public safety officials to make clear that mob rule and acts of violence will not be tolerated in our state,” Moore’s statement said.

Smith said he wanted the board to hire an independent firm to study what happened on Aug. 20 — with an eye toward whether anyone in the UNC administration or campus police gave any orders other than full protection of the statue during the rally.

Late Aug. 21, Folt addressed the issue in a statement to the campus community that also was signed by Smith, Spellings and Cochrane: “Since the Confederate Monument was brought down last night, many have questioned how police officers responded to protesters and how the University managed the event. Safety is always paramount, but at no time did the administration direct the officers to allow protesters to topple the monument. During the event, we rely on the experience and judgment of law enforcement to make decisions on the ground, keeping safety as the top priority.”

She added, “This protest was carried out in a highly organized manner and included a number of people unaffiliated with the University.”

There also has been talk among BOG members and members of the General Assembly that the statue should be replaced; the 2015 law stipulates that any monument removed temporarily must be replaced within 90 days.

The North Carolina division of Sons of Confederate Veterans sent a letter to Folt on Aug. 21 demanding that Silent Sam be “put back in its rightful place.”

The outcry against the monument’s continued presence has grown louder in the past 10 years. An organization of students and others called the Real Silent Sam Coalition emerged in about 2011, calling the statue offensive to people of color and at first suggesting UNC erect a reinterpretation plaque to explain it.

Students have said they are insulted by its presence — what they call a symbol of the Confederacy’s loyalty to the institution of slavery — some adding that they didn’t feel safe when counterprotesters came to the campus.

Others see Silent Sam as a tribute to those who fought for their homeland in the Civil War, perhaps without regard to the slavery issue. Many have said that removing the statue would be detrimental to the understanding of history.

Rallies grew angrier about the time that the UNC trustees voted in May 2015 to change the name of Saunders Hall; William Saunders, an 1854 graduate of UNC, was the North Carolina leader of the Ku Klux Klan in the late 19th century.

One year ago, on the eve of the start of classes, UNC Police erected two concentric circles of steel barricades around Silent Sam in anticipation of a protest rally that also included supporters of the statue that evening, amid talk that the statue might be taken down. That protest, which came in the wake of a rally by white nationalists in Charlottesville, Va., was the largest before the Aug. 20 event.

Cooper at that time said that UNC officials could take the statue down as a safety measure, but campus administrators cited a state law that prohibits removal of historic monuments. Folt and others have said repeatedly over the past year that they would like to see it removed.

The University spent about $390,000 to provide police security for the area around the statue between July 2017 and this past June.

Silent Sam was commissioned by the Daughters of the Confederacy and finished in 1913. It was erected, as the Alumni Review reported at the time, “in memory of all University students, living and dead, who served in the Confederacy.”

One of the speakers at the dedication, Julian S. Carr, an 1866 graduate, hailed Confederate soldiers as the saviors “of the Anglo Saxon race in the South.” Carr told the crowd he had “horse-whipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds” within sight of the statue after she allegedly offended a white woman on Franklin Street.

When the trustees voted to rename Saunders Hall — now known as Carolina Hall — they also enacted a 16-year moratorium on renaming buildings. The campus has several buildings named for individuals who have been identified as white supremacists.

A University task force is at work carrying out a three-year-old directive from the trustees that signs be placed in McCorkle Place, the oldest quad on the campus, to address issues of race in UNC’s past.

A Timeline of Silent Sam and Related Issues

Calls for the removal of the Confederate statue Silent Sam — and rallies for its support — have occurred periodically for decades. This timeline is not all-inclusive.

1908 Trustees approve erection of a monument by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in memory of UNC students who joined the Civil War effort. 1913 Dedication of what was then called the Soldiers’ monument includes a speech by Confederate veteran, trustee and industrialist Julian S. Carr (class of 1866) that includes an account of having “horse-whipped a negro wench” near the site, because “she had publicly insulted and maligned a Southern lady.” 1954 Apparently first use of the name Silent Sam, in The Daily Tar Heel, due to the fact the soldier carried no ammunition. 1965 A letter appears in The DTH that asks whether the statue is a racist symbol that should be removed. 1968 Graffiti appears on Silent Sam at the time of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. 1971 and again in 1973, UNC’s Black Student Movement holds protests at the statue after the deaths of black men killed by a motorcycle gang and by police. 1992 Silent Sam is the site chosen for Chancellor Paul Hardin and others to speak to students about the controversial beating of Rodney King by the Los Angeles police and the issue of whether UNC should erect a freestanding Black Cultural Center. 2000 February: Gerald Horne, then director of UNC’s Black Cultural Center, writes a newspaper column in which he likens the statue to a Confederate battle flag and says it was hypocrisy and slavery denial for UNC to leave it standing. 2009 While doing research in the Southern Historical Collection at Wilson Library, Adam Domby, then a graduate student in history, finds Carr’s speech from the 1913 dedication. He shows it to other historians; none had seen it before. 2011 January: Domby writes a letter to The Daily Tar Heel with excerpts of Carr’s speech, bringing Carr’s words to public attention. September: Members of the Real Silent Sam Coalition hold a protest at the statue, calling it offensive and suggesting UNC erect a reinterpretation plaque to explain it. 2015 January: Students lead a large, angry rally around Silent Sam, demand the renaming of Saunders Hall for author and activist Zora Neale Hurston. April: UNC trustees hold a special meeting to hear comments on the name-change issue. May: Trustees vote 10-3 to change Saunders to Carolina Hall, approve a 16-year moratorium on other renamings and order “curating” of UNC’s racial history. July: Vandals deface Silent Sam, painting “KKK” and “murderer.” N.C. General Assembly enacts a law prohibiting removal of any publicly sited “monument of remembrance.” September: Chancellor Carol L. Folt announces a task force to carry out the trustees’ directives. November: Students of color speak out at a large rally outside South Building in the aftermath of racial unrest at the University of Missouri; a week later, a town hall meeting fills Memorial Hall, where students present a long list of demands. 2016 January: Chancellor Folt meets with leaders of the movement, who amplify demands; later she reports to the campus on required racial sensitivity training for administrators and a dedicated gathering place for black students, and she promises results of a survey on diversity. November: Carolina Hall lobby display is unveiled. 2017 August: UNC Police erect two concentric circles of steel barricades around Silent Sam in anticipation of a protest rally that evening, amid talk that the statue might be taken down. Gov. Roy Cooper ’79 (’82 JD) tells UNC officials they can take it down in the event of an imminent threat to public safety and security. University and UNC System attorneys decide not to challenge the law. November: Trustees hold a listening session on Silent Sam — 28 people speak, two of whom support keeping the statue. Folt says: “I’d like to reiterate that, if I had the authority, in the interest of public safety, I would remove the monument to a safer location on our campus, where we could preserve, protect and teach from it. What I heard yesterday reinforced that belief.” A campus police officer goes undercover at the statue to engage both sides in conversation. 2018 May: Graduate student Maya Little throws red ink and what she says was her own blood on Silent Sam in full view of the police assigned to protect it and is arrested. July: UNC reports it spent about $390,000 to provide police security for Silent Sam, July 2017 through June 2018. Aug. 20: A Franklin Street protest is a diversion for an organized offensive on the statue, and protesters pull it off its pedestal, igniting a response marked by jubilation and by angry street confrontations. Aug. 25: A group of Confederate monument supporters clashes just off Franklin Street with those supporting removal. Aug. 28: Board of Governors passes a resolution directing Folt and the trustees to come up with a “lawful and lasting” plan to preserve the monument with attention to safety, and it sets a Nov. 15 deadline. Aug. 31: As of this date, a total of 17 people had been arrested related to three protest events; of those, 16 were not affiliated with the University. December: UNC announces it will ask for the Board of Governors’ approval to build a $5.3 million Center for History and Education, where Silent Sam would be on display indoors. In mid-month, the Board of Governors rejected that proposal and set up a five-member task force of its members to work with trustees, the chancellor and UNC’s top administrative staff to come up with another plan for Silent Sam by March 15.