Panel Divided on Merits of Affirmative Action in Admissions

A panel on affirmative action that included three professors who specialize in economics, linguistics and law couldn’t come to consensus last week about whether race should be considered a factor in college admissions, though one panelist was adamant it should not.

“How many classes is diversity of experience useful in?” asked John McWhorter, an associate professor in linguistics in the Slavic department at Columbia University. “I teach some, but I teach more where it isn’t. If you’re learning Italian irregular verbs, what color you are and where you came from isn’t going to help. It’s not going to help if you’re learning about systolic pressure. It’s not going to help in physics. It’s not going to help in the vast majority of classes, and we all know it. And so, why are we using that particular rationale?”

McWhorter spoke during a Feb. 24 panel titled The Future of Affirmative Action at Frank Porter Graham Student Union auditorium. The discussion, sponsored by UNC’s Program for Public Discourse and the GAA, kicked off the spring semester for the Program for Public Discourse’s Abbey Speaker Series. Theodore Shaw, the Julius L. Chambers Professor of law and director of UNC’s Center for Civil Rights, moderated the panel.

In October, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in two linked cases involving UNC and Harvard University that revisited decades-old precedents allowing universities to consider race in a limited way when making admissions decisions. The case was brought by the advocacy group Students for Fair Admission Inc., which argued by making race even one of many factors in the admissions process, UNC and Harvard effectively discriminate against applicants who aren’t Black, Hispanic or Native American. A ruling is expected this spring.

Panelist Rachel Moran, Distinguished and Chancellor’s Professor of law at UC-Irvine, who studies higher education and affirmative action, said she’s worried the Supreme Court will rule diversity isn’t a compelling interest because academic freedom doesn’t appear in the text of the constitution.

“The diversity rationale is rooted in academic freedom, so it’s a liberty interest,” Moran said. “The reason that colleges and universities can use race in admissions, whereas other institutions cannot, is because they have academic freedom to create their student bodies, where the ferment of ideas will take place. So, I actually don’t have as dim a view of the diversity rationale.”

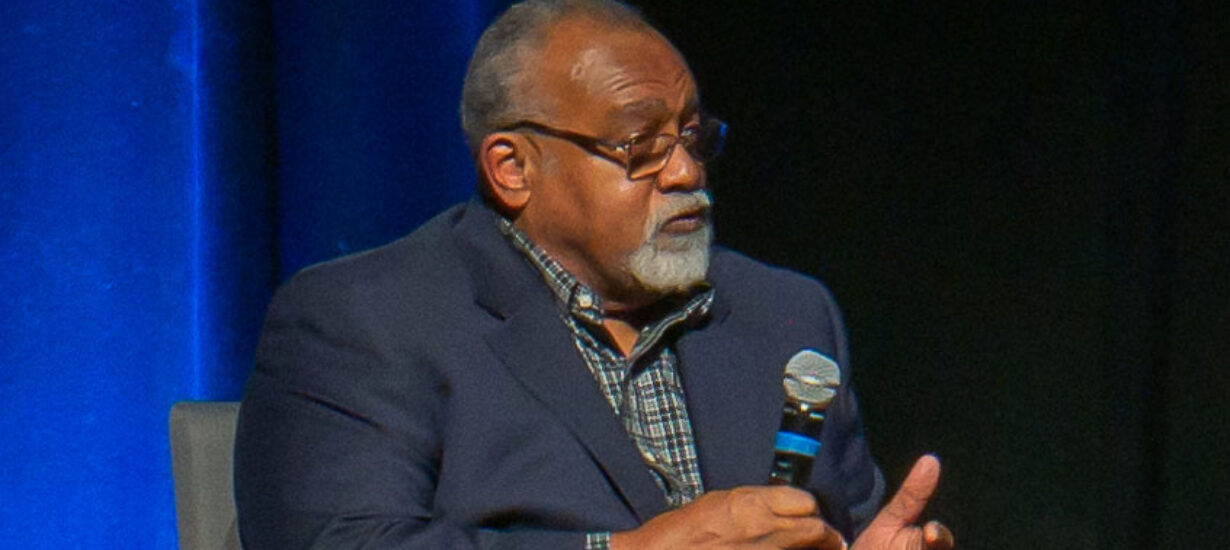

Glenn Loury, the Merton P. Stoltz Professor of the social sciences and an economist at Brown University, said there was a need for affirmative action in 1978 when the Supreme Court ruled in the landmark case Regents of University of California v. Bakke, which addressed whether preferential treatment for minorities can reduce educational opportunities for white people without violating the constitution.

“But that was 45 years ago,” Loury said. “The permanent reliance upon a special dispensation for people who descend from slaves, that the criteria of assessing excellence would be differentiated in their case, made lower, less exacting, more giving — this is not a path to equality. So, I think we’re at an impasse here.”

Loury stopped short of taking the position that affirmative action is by fact wrong or racial discrimination in reverse but questioned whether it is beneficial. “Is this good for America, and even is it good for Black people in the end that we not be asked to do what others are being asked to do?” he said.

Several hundred people attended the panel in person, while others watched via Zoom. Shaw, who teaches civil procedure and advanced constitutional law and whose research areas include the Fourteenth Amendment, affirmative action and fair housing policies, opened the discussion by asking the panelists why they were in attendance.

Loury said there couldn’t be a more important discussion. “The country’s gone through many changes and evolutions and so on,” he said. “It was [Supreme Court Justice] Sandra Day O’Connor in 2003 who said, ‘I hope we won’t be in this business 25 years from now,’ and we’re pretty close to 25 years and we’re still in this business. You know the Supreme Court’s composition better than I do. … Stuff is going to hit the fan. It’s worth talking about, so I’m here to talk about it.”

McWhorter said he’s “utterly disgusted” with the way affirmative action is discussed in the United States. “I feel like it’s a public mission to start having an honest, constructive discussion about what racial preferences consist of and where we go in the future,” he said. “We’re supposed to think that the way racial preferences go is that people with equal qualifications are assembled and then someone decides how you’re going to slice up the pie in terms of diversity. The problem with that version of racial preferences is it’s a lie. … Racial preferences is about lowering standards.”

Moran said the cases before the Supreme Court matter to her because of “pluralism anxiety,” a term coined by Kenji Yoshino, the Chief Justice Earl Warren Professor of constitutional law at New York University, to describe apprehension associated with the nation’s changing demographics.

“We’re seeing a destabilization of our fundamental principles, and that’s why programs like this are so important,” Moran said. “We’re seeing polarized discourse and we’re seeing a contest over, for example, what merit means. This case tests that. What does academic freedom mean? This case tests that. And what does race mean? This case tests that, too. The court is one way to have the conversation, but I think there are many other ways. I think it’s especially important because colleges and universities shape youth.”

The Supreme Court seems poised to alter or overturn decades of precedent around race in college admissions. During more than five hours of oral arguments on Oct. 31, lawyers representing the two universities faced a barrage of skeptical questions about whether to allow even a limited consideration of an applicant’s race.

In October, Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz said diversity is a fundamental value that is core to Carolina’s mission. In court documents, UNC has maintained an applicant’s race “is only one among dozens of factors that UNC may consider as it brings together a class that is diverse along numerous dimensions.”