Picture This: James Walker, Remembered

Posted on Sept. 15, 2020

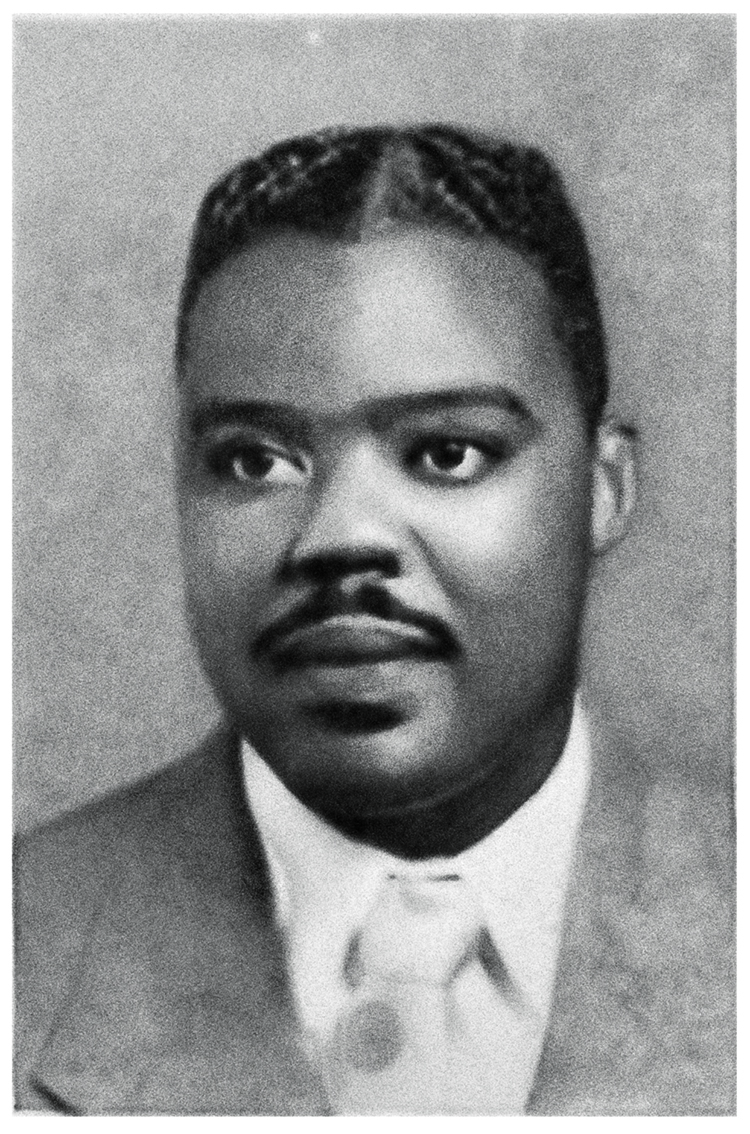

James R. Walker Jr. as he appeared in the Yackety Yack in 1952.

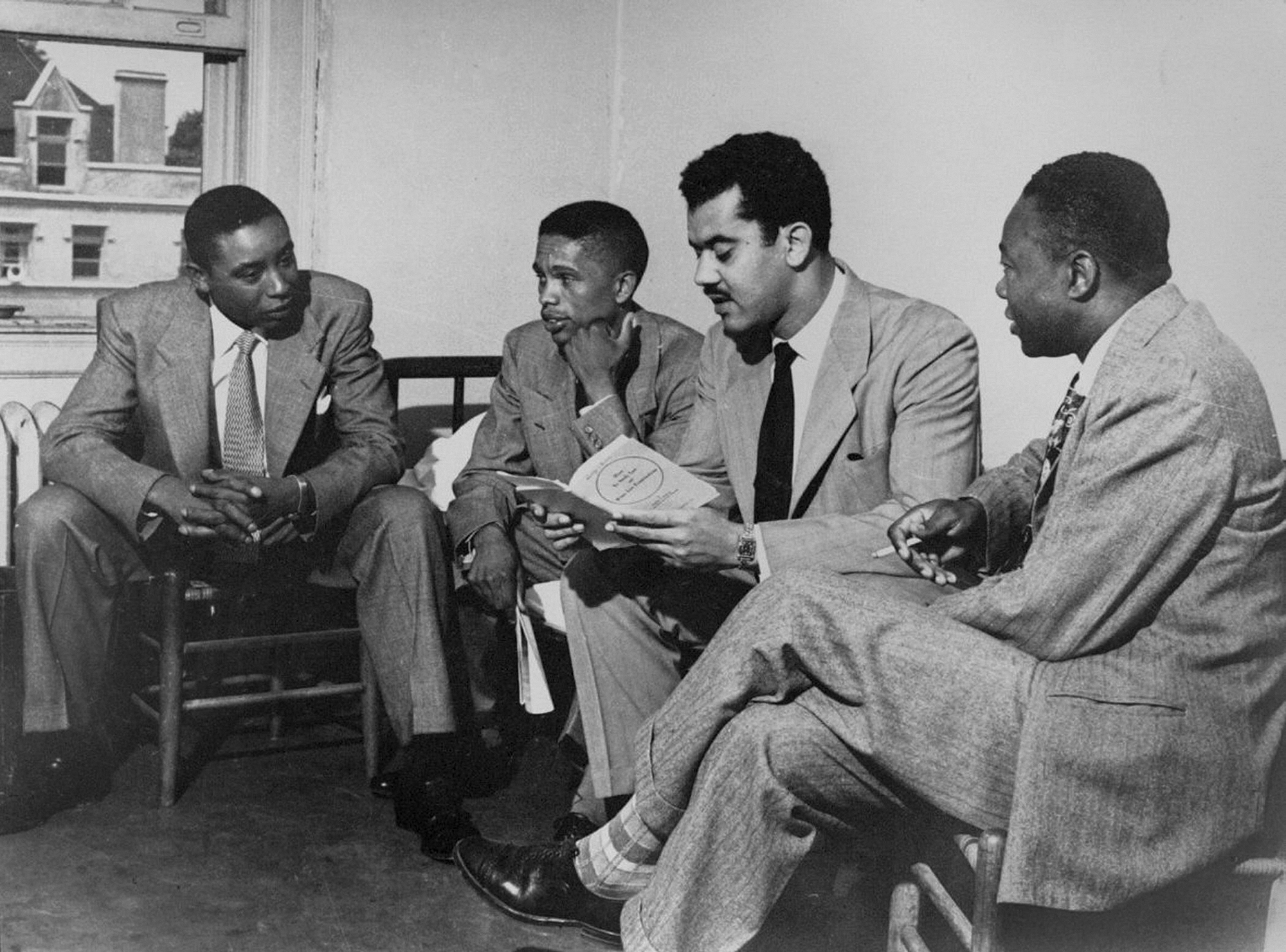

Someone was missing from a photograph this magazine published 18 years ago. Floyd McKissick Sr. ’51, Kenneth Lee ’52 (LLBJD), Harvey Beech ’52 (LLB) and James Lassiter ’55, dressed in suits and huddled together, likely were discussing the lawsuit with which they broke down UNC’s segregation door.

James R. Walker Jr.’s absence from the picture led to an assumption that the four were the complete group. It shows with what ease pioneers can be forgotten. The story went on without him.

Walker, too, has a ’52 (LLB) by his name, and what he did with it has moved Carolina’s oldest student organization to push for a singular honor: The grassroots civil rights litigator would be the first African American to have his portrait on the wall in the chambers of the Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies.

The University fought for years to keep Blacks out of the student body. By the early 1950s, the courts were sending strong signals that it was a losing battle. In 1951, McKissick had been trying for five years to enter Carolina’s law school, even while he worked toward that degree at N.C. College (now N.C. Central University). A federal District Court stood up for Carolina again in fall 1950, but it would be one of the last stands.

In March 1951, UNC’s trustees’ executive committee recommended admittance in programs that did not have similarly endowed programs elsewhere in the state. There were no medical, dental or public health schools for Blacks, and N.C. College’s law school was ruled too inferior to Carolina’s.

The original photo of Black law school pioneers published in the Review. Left to right: Floyd McKissick Sr. ’51, Kenneth Lee ’52, Harvey Beech ’52 and James Lassiter ’55. Absent from the photo is fellow pioneer James R. Walker Jr. ’52. (Rivera photo)

But except for Lassiter, who was in middle age when he earned his degree, James Walker had nine or 10 years on the other first graduates. He was born in Ahoskie in northeastern North Carolina, the son of teachers with advanced degrees and the grandson of a preacher. He grew up to the west in Statesville, raised by his maternal grandmother, and lived there for much of his life. His seven siblings all went to college.

Walker already was most of the way to an undergraduate degree when he was drafted into the Army in World War II. He had studied German, geography and history, and his denial by Officer Candidate School made him bitter. He fell into what he called a segregated unit under the command of a white officer he described as a “former soda jerk with no college training.”

“We were supposed to be fighting for the Four Freedoms,” he wrote later. “I had never seen any of them.” That’s what led him to civil rights law — it’s the specialty that all of the early Carolina Black law graduates settled in.

At Chapel Hill, Walker joined off-classroom battles to close a section of Kenan Stadium designated for Blacks to keep them from mingling with their white classmates. Then, as the law students planned their spring dance, he sent a letter to Chancellor Robert House (class of 1916).

“I will never accept the denial of a privilege,” Walker wrote. “I have made footprints around the world defending a free society.

“Personally, I do not care for dances.” But a vote against letting people of color attend “meant that the person was willing to disregard the rights and privileges of a fellow student.”

As a lawyer, Walker had a reputation as a lone wolf in the trenches to secure basic voting rights for individual clients in the Jim Crow era in some of North Carolina’s poorest areas.

He went where other lawyers told him he’d be spinning his wheels. Early in his career, he often worked out of an old car, rarely made any significant money and sometimes was at odds with the NAACP, which sought precedent-setting cases and was reluctant to work with somebody who would take all comers and suffer setbacks that could slow the group’s efforts.

Walker was behind a wall listening when one hopeful voter was mistreated by a registrar armed with a literacy test and unassailable discretionary power to use it indiscriminately.

He was arrested for arguing with registrars, but his persistence eventually contributed to changes that would allow for appeals of their rulings. When the Voting Rights Act of 1965 passed, his work was in the pile of grassroots cases — some successful, many not — that pushed it through.

“He was passionate to a fault, relentless and determined,” his daughter, Pat Ford, told the audience at last fall’s DiPhi kickoff for a campaign to raise funds for the portrait. “Those same attributes made him appear arrogant and indignant. And yet, these are the characteristics and traits that made him great at what he did. Pity the fool who would try to get in his way or stop him.

“He used to make LaVone, my baby sister, and I sit still and listen to the details of the case or cases he was arguing, like persons on a jury. We would often tune him out, not realizing we were tuning out history.

“He was an advocate for the poor and oppressed. Instead of charging money for those who were indigent, if they had a car, he would barter the car for me to drive while I was attending undergrad at Johnson C. Smith in Charlotte. That was his payment.”

Growing up with James Walker had heartbreaking moments.

“I used to call him ‘a visiting father’ because he was taking on cases of people who were being taken advantage of,” Ford said.

Ford’s and LaVone Hicks’ parents didn’t marry, and Walker knew there were career consequences for having illegitimate children at the time. Once, when Hicks proudly introduced him to classmates, he corrected her: “No. I’m her uncle!”

But when Ford faced racism in high school, her father went straight to the principal’s office — “He would go from zero to 100 when he made his case,” Ford said — waved a yellow legal pad and threatened to sue. She’s not sure of all he said, but thereafter she was treated with a lot more dignity.

Ford and Hicks are working today to remove the name of Charles B. Aycock (class of 1880) from that school; the name was removed from a residence hall at UNC this summer because of the former governor’s white supremacist views.

In her turn at the DiPhi podium, Hicks said: “The mission he was on was bigger than our family. Like Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, he made personal sacrifices to help the masses.”

Adding to the collection

The DiPhi, now a single entity merged from the University’s two oldest student organizations, is the founder and keeper of a portrait collection begun in 1818. Among its artists are masters Thomas Sully, Eastman Johnson and Charles Willson Peale. Its subjects are Carolina’s famous, mostly from the 19th century.

Considered one of Carolina’s foremost treasures, it is counted by the society as the largest privately owned portrait collection in the Southeast. Including busts, prints and photographs, it totals 110 pieces. It was collected by students and is owned by them.

Some 40 of the portraits hang in the chambers in New West and New East, and some are scattered about the campus, but most are stacked in storage. The most recent one commissioned was of Thomas Wolfe (class of 1920) in the 1970s, and there may have been a gap of 50 years before that one.

In October 2019, the Di chamber filled with student members and invited guests, among them James Walker’s family, for the portrait commissioning fundraising kickoff. Again, the society is aiming high: Simmie Lee Knox, who painted Bill and Hillary Clinton’s White House portraits, is being solicited.

“For me personally, it’s this sense of admiration about [Walker] and his work,” said senior Maggie Pollard, president of the DiPhi Senate. “He is not as well known as some of the other members of that first integrated UNC law school. But for me, James Walker Jr. is just as accomplished and hasn’t gotten the same amount of recognition.”

LaVone Hicks said, “I think he rightfully needs to be up there with those other portraits.”

Pat Ford put it more succinctly: “If my dad was alive, he’d be standing up there yelling, ‘It’s about time.’ All the other pictures are going to fall off the wall!”

— David E. Brown ’75

More:

“A Grudging Acceptance,” marking 50 years after Carolina accepted its first Black students, May/June 2002 Review

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.