Pictures Worth a Thousand Words

Posted on Nov. 12, 2018

Ann Moss Joyner ’81 (MBA) and Allan Parnell ’76 originally set out on separate career paths. Then in 2000, after nine years on the farm, an electrical fire burned their home to the ground and forced them to start over. (Anagram photo/Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

Life was pretty sweet for an ambitious alumni couple. Then misfortune found them, and they turned their talents to those who are mapped out.

by Elizabeth Leland ’76

At the end of a long dirt road in rural Orange County, past grazing horses and fields of wild daffodils, Ann Moss Joyner ’81 (MBA) and Allan Parnell ’76 are working at their computers inside a renovated Primitive Baptist church. A hand-stitched quilt hangs on the planked wall where the altar once stood. Vintage stained glass filters light through the windows.

Joyner and Parnell are dressed in jeans and dusty work shoes. On the barn-red floor between them are the two Rhodesian Ridgebacks and the dachshund they rescued. Outside, a brood of hens pecks through the dirt.

Parnell is usually the first one up in the morning. He takes the dogs for a walk, listens to the news on public radio during breakfast, then heads over to the renovated church, a short stroll past their fishing pond. Joyner feeds and grooms the six horses on their 48-acre farm and tends to other chores before working alone for a few hours on a laptop in their living room. She’s in charge of their extensive flower gardens. Parnell oversees the vegetable beds outside the kitchen.

They originally set out on separate career paths. Then in 2000, after nine years on the farm, an electrical fire burned their home to the ground.

They had only time enough to rescue their photo albums. Family heirlooms, antique furniture, Joyner’s collection of Seagrove-area pottery, all their artwork — everything was gone. After a few days spent grieving and reorienting themselves, Joyner got busy again. She redrew the design for the house, with a gable roof above the front porch — like the original — and started over.

In the ashes of the fire are clues to their migration from separate pursuits to one.

Parnell, a demographer by training, had done population research, most recently at the University’s Carolina Population Center; in addition to his undergraduate degree from Carolina, he received his master’s and his doctorate from UNC, the first in 1983 and the second in ’87. Joyner was a newspaper reporter who went into management consulting and then real estate.

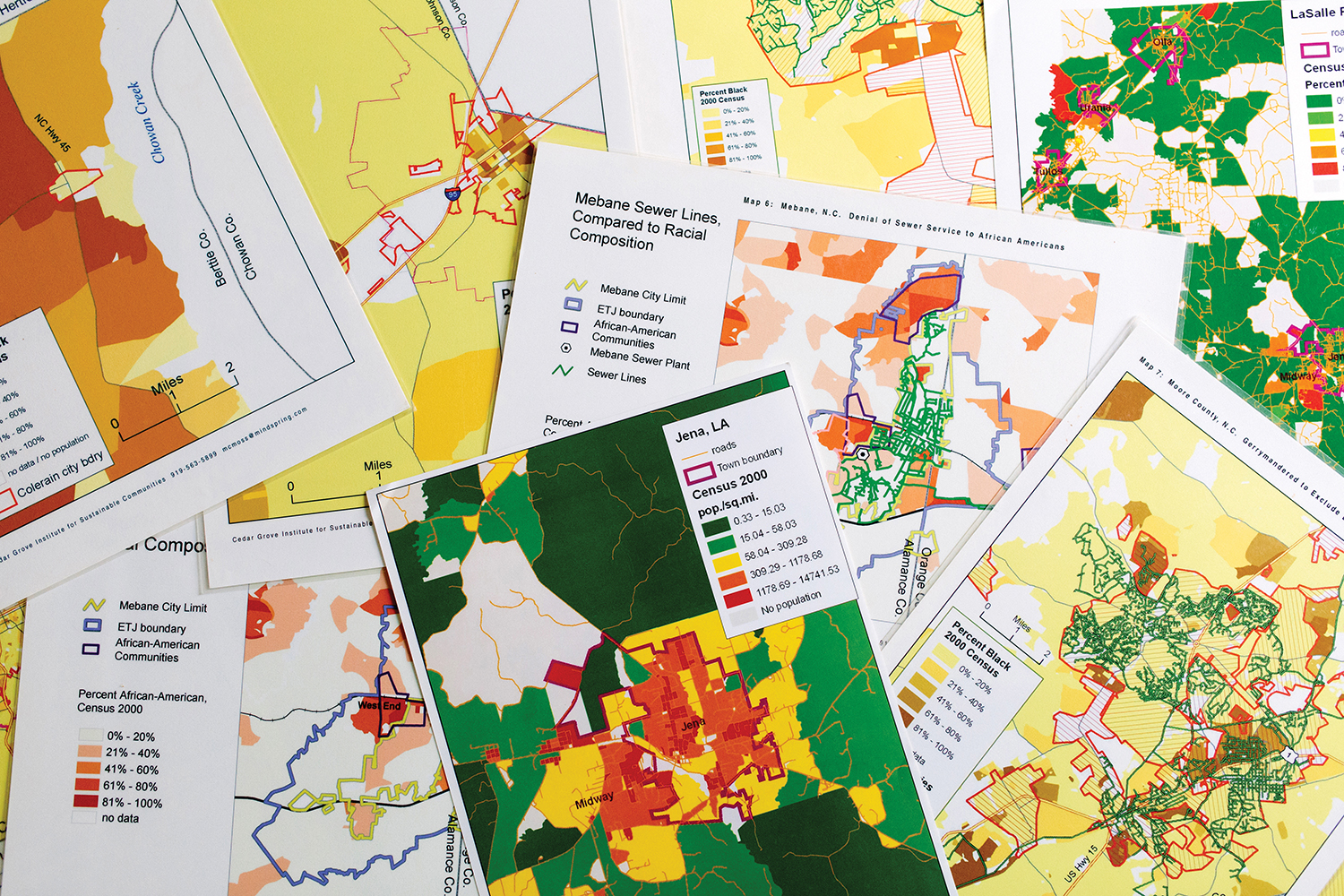

For the past 16 years, their business has been uncovering institutional racism by overlaying U.S. Census maps with computerized Geographic Information System data to expose links between the race of residents and their access to water, sewer and other public services in towns and cities across America. (Anagram photo/Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

For the past 16 years, their business has been uncovering institutional racism by overlaying U.S. Census maps with computerized Geographic Information System data to expose links between the race of residents and their access to water, sewer and other public services in towns and cities across America. The connections often are alarmingly strong. Their work was so cutting-edge when they started, it earned them a nickname: “The mapping people.”

They had received a lot of help after their loss, and Parnell said their shift into social advocacy is no coincidence.

“It made us ready to try something bigger, something to have an impact,” he said. “Losing everything you own kind of makes you look at life a little differently. We didn’t know where the work was going. But we were much more open to doing something bigger.”

When you map it, you see it

Two years after the fire, Parnell got the call from a Mebane activist concerned about conditions in his neighborhood.

It was 2002. Parnell was at his desk at the population center, researching abortion policy. His focus was North Carolina. So when the receptionist answered a call from someone from Mebane, 20 miles north of Chapel Hill, she forwarded it to Parnell.

“Be careful when you take a phone call,” he deadpanned.

A community activist wanted help for his neighborhood, where former enslaved men and women settled after the Civil War. He said residents had been excluded from the town limits for more than a century with no water or sewer services and no right to vote on development issues, including a proposed bypass that would run through their neighborhood.

As a fertility expert, Parnell didn’t think he could be of much help. But he was intrigued.

“I had lived around Mebane for 20 years, and I had no idea this was going on. They’re in what we call the ecological town but not the political town. Until you map it, you don’t see it.”

Parnell mapped it.

With the help of Ben Marsh, a friend and colleague at Bucknell University, he layered the location of water and sewer services with the racial makeup of neighborhoods. The map showed disparities that were invisible when driving through town: While richer and whiter neighborhoods were annexed and benefited from municipal services, poorer black neighborhoods were not.

“I was outraged,” Parnell said. “I started driving around looking for manholes.”

Joyner offered to dig through 20 years of city council minutes, tax files and other public records to check for patterns of racial discrimination. From her years as a journalist and developer, she understood government regulations and land records, and she knew where to look.

A shared passion was born.

Despite being labeled “scurrilous communists” by a town councilman — or maybe because of it — they formed the Cedar Grove Institute for Sustainable Communities to help other disadvantaged communities. They launched their new venture with grants from Chapel Hill’s Warner Foundation and North Carolina’s Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation to study racial exclusion in North Carolina towns.

“We weren’t getting paid much of anything for doing this for a good while,” said Joyner, who continued to dabble in real estate to pay the bills and still does.

“As a way to get rich, we don’t recommend it,” Parnell added.

They share a love of bluegrass music and Tar Heel basketball and a fondness for good books, good food and good friends. He calls her “the risk taker” in their relationship. But for her, he says, he might be quietly working in academia and living in a townhouse. (Anagram photo/Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

One of their first studies revealed that five unincorporated minority communities in Moore County were controlled by the towns of Pinehurst, Southern Pines and Aberdeen but lacked municipal services. When it rained, raw sewage from septic tanks flooded some yards.

Carol Henry is a community leader in Jackson Hamlet, one of the affected neighborhoods. She credits Joyner and Parnell with getting them the attention they needed. “They worked hard to try to let people know what was going on,” Henry said. “They are genuine. They’re down-to-earth people just like us.”

The findings, released shortly before Pinehurst hosted the U.S. Open in 2005, thrust their work onto the front page of The New York Times, where a headline announced: “In County Made Rich by Golf, Some Enclaves Are Left Behind.”

As their exposure grew, so did their business.

They have conducted research for organizations as varied as the National Institutes of Health, the UNC Center for Civil Rights, Great Schools in Wake and California Rural Legal Assistance. Both have testified as expert witnesses in court in civil rights cases across the country — from fair housing to environmental racism to education.

One map showed that the public water line in Zanesville, Ohio, stopped just before an African-American neighborhood. Another showed sidewalks and streetlights in Modesto, Calif., ending where neighborhoods with 20,000 Latino residents began. And then there were the “doughnut holes” within the town of Pinehurst where poor, minority neighborhoods had never been annexed or provided services.

The creator of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee, included their map of Zanesville, Ohio, in a 2010 TedTalk as an example of what can be discovered by connecting different types of data.

“This wasn’t a career path,” Parnell said. “It happened all by accident. But it’s easy to be passionate about. It just kind of took over our lives.”

Jurors could see it

In 2008, Parnell was on the witness stand, explaining his maps, in a lawsuit brought by residents of the Coal Run neighborhood of Zanesville. They alleged that the city had refused to provide them water service for more than 50 years because they lived in the only predominantly African-American neighborhood in a virtually all-white county.

Using data from public records, Parnell and Joyner matched the race of residents with whether they got water service. Although compiling data can be complicated, the maps they created to illustrate their findings are easy to read. A blue water line runs along streets in a neighborhood of tiny white houses — representing the race of residents who live there. The line ends abruptly before an adjoining neighborhood where all but one of the houses are black.

“The groundwater was contaminated from coal mines,” Parnell recalled. “The residents would have to catch rainwater or go to the county water facility and fill up barrels. We mapped it house by house, race by race, by who had water. The water line stopped at the last white house.”

When jurors left the courtroom for a recess, Parnell said U.S. District Judge Algenon Marbley motioned for him to approach the bench.

“UNC class of ’76?” the federal judge asked.

“Yes, your honor.”

The judge graduated the same year. And so, for a few moments, two Carolina alumni had a reunion moment as a courtroom of astonished attorneys listened in.

“This wasn’t a career path. It happened all by accident. But it’s easy to be passionate about. It just kind of took over our lives.”

–Allan Parnell ’76

Sixty-seven plaintiffs testified during the seven-week trial. Lawyers asked each plaintiff to point out on Parnell’s maps where he or she lived. Sixty-seven times, residents pointed to one of the little black houses without water service.

It wasn’t just numbers and testimony. Jurors could see it.

“The maps were really, really powerful,” said attorney Reed Colfax, who represented the residents. “In this day and age, there are a lot of people who don’t believe there’s much discrimination left in the country or believe that the effect of past discrimination has gone away. We realized early on in the case that to be able to show the judge and show the jury exactly what was happening with the water lines going all around and serving all the white residents and not this black neighborhood — putting that in a picture — would be helpful.”

When the jurors ruled against the city of Zanesville for denying water service to the predominately African-American community, they cited the maps as a key reason why. They awarded nearly $11 million in damages, and residents of Coal Run finally had running water.

James H. Johnson Jr., Kenan Distinguished Professor in UNC’s Kenan-Flagler Business School, described the work that Joyner and Parnell are doing as ground-breaking. “They’re uncovering things you would think would have been eliminated a long time ago,” he said.

Joyner and Parnell have been involved in a number of other successful lawsuits. Parnell testified in a Texas case that resulted in a favorable ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court about housing discrimination. Joyner wrote a report as an expert witness in a California case that ended with a $5.25 million settlement to three group homes, which would have been forced to close under a new city ordinance.

“We weren’t getting paid much of anything for doing this for a good while,” says Ann Moss Joyner ’81 (MBA). (Anagram photo/Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

In a Brunswick County environmental justice case, Joyner presented evidence of discrimination on behalf of residents who opposed a landfill expansion near their historic African-American community, already buffered by an open landfill, a waste transfer station, a sewage treatment facility, an animal shelter and a hog farm. The county abandoned its plans and designated the land for a school instead.

In April, the Fair Housing Project of Legal Aid of North Carolina saluted their work by awarding Cedar Grove Institute its Stella J. Adams Fair Housing Advocate Award “in recognition of its longstanding commitment to the fair housing and civil rights of all North Carolinians.”

Johnson, who has collaborated with Parnell and Joyner on some cases, credits their success to a unique blend of expertise: “Ann, with her incredible business and developer background, in combination with Allan, who is an excellent demographer. They’re able to look through diverse academic lenses and identify issues that most people are not able to do. It’s a powerful combination.”

Educators, too

The fact that when they met both were reading Ken Kesey’s Sometimes a Great Notion may have been a clue to how well they are suited. They share a love of bluegrass music and Tar Heel basketball and a fondness for good literature, good food and good friends.

They raised their daughter, Hannah, 26, on a love of horses and the outdoors. She now works for a garden designer in Asheville, where she went to college. “Hannah used to joke that we worked for the CIA,” Joyner said, “because what we do is so hard to describe.”

Joyner focuses on culling facts from public records. “She just gets in there and digs and digs and digs,” Parnell said.

Parnell, who also is a senior fellow at UNC’s Frank Hawkins Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise, undertakes the complicated statistical analyses. “He’s very good at what he does, but most of the stuff is so dry,” Joyner said. “He’s really good at helping the attorneys narrow in on the most important point.”

To educate people about the issues and the evidence, the couple have spoken at more than 100 conferences and colleges, from Cornell to San Diego (Joyner) and from Albany to Seattle (Parnell).

Around midday, Joyner joins Parnell in the office. They work side by side for a few hours until he leaves to start dinner. She keeps working until it’s almost time to eat and then makes a salad.

“The way that we get along is everything is compartmentalized,” she said. “We only ask the other person’s help by calling on each other’s strengths or seeing if we can do something for the other person.”

The view of the former church office from Ann Joyner’s and Allan Parnell’s front porch. (Amnagram photo/Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

Parnell, who is a lay Eucharistic minister at St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church in Hillsborough, calls Joyner “the risk taker” in their relationship. He said he probably would be quietly working in academia and living in a townhouse if they hadn’t fallen in love.

She wanted horses and donkeys, but they couldn’t afford land. So she took out a loan and bought a large swath of undeveloped property five miles from Mebane, kept a piece for themselves and subdivided the rest into 10-acre lots that she marketed as an equestrian community with three miles of trails snaking through the woods. She designed their first home to look like old farmhouses common in the area. Next, she bought the abandoned church and had it moved to their land and restored.

“I tell people my wife is a doer,” Parnell said. “She gets things done, whether it’s at work or at home. Who else would move a church eight miles to be an office?”

This past March, Parnell was invited to speak to students and faculty at the Carolina Population Center, where he did his graduate research on the relationship between the timing of first marriage and the timing of first birth from the mid-1950s through the mid-’70s.

He often jokes that he’s “just a country demographer.” But on that Friday, he traded blue jeans and sneakers for black dress pants and dress shoes.

Dr. Parnell the professor stood in front of the seminar room with PowerPoint slides of maps and graphs.

“He, more than anybody else I can think of, represents an engaged scholar from demography,” Barbara Entwisle, Kenan Distinguished Professor of sociology, told the gathering. “Most of us doing research are very removed from the social issues that affect us.”

Parnell titled his talk “Planning Racial Inequality” and assured the students it wasn’t a typo.

“What I want to talk about is built on racial residential segregation and the continued effects it has on our country. It involves

the nitty-gritty of local government: how they shaped and maintained a landscape of inequality through zoning, permitting and annexation.”

When he and Joyner launched the Cedar Grove Institute in 2002, he said they thought they would uncover disparities mostly in small Southern towns. The practice, they discovered, is pervasive. Much of it dates back 100 years to when government policy mandated segregation. In some communities, officials aren’t even aware of the modern-day impact of outdated policies; in others, they believe, officials deliberately perpetuate the inequities.

Case by case, Parnell outlined instances of “institutional discrimination” from North Carolina to Ohio to California, in big cities and small towns: White neighborhoods had public services while minority neighborhoods did not.

He told them he used to do fertility research, “believe it or not.”

He then told the story about that call from the community activist in Mebane. “I hemmed and hawed,” Parnell said. “I’d never gone out and done this kind of stuff. I wasn’t a social justice kind of person.”

But sometimes in life, he said, you see something and you just can’t walk away.

Elizabeth Leland ’76 is a freelance writer based in Charlotte.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.