Prohibit Civil Rights Center From Litigating, BOG Panel Says

Posted on Aug. 1, 2017

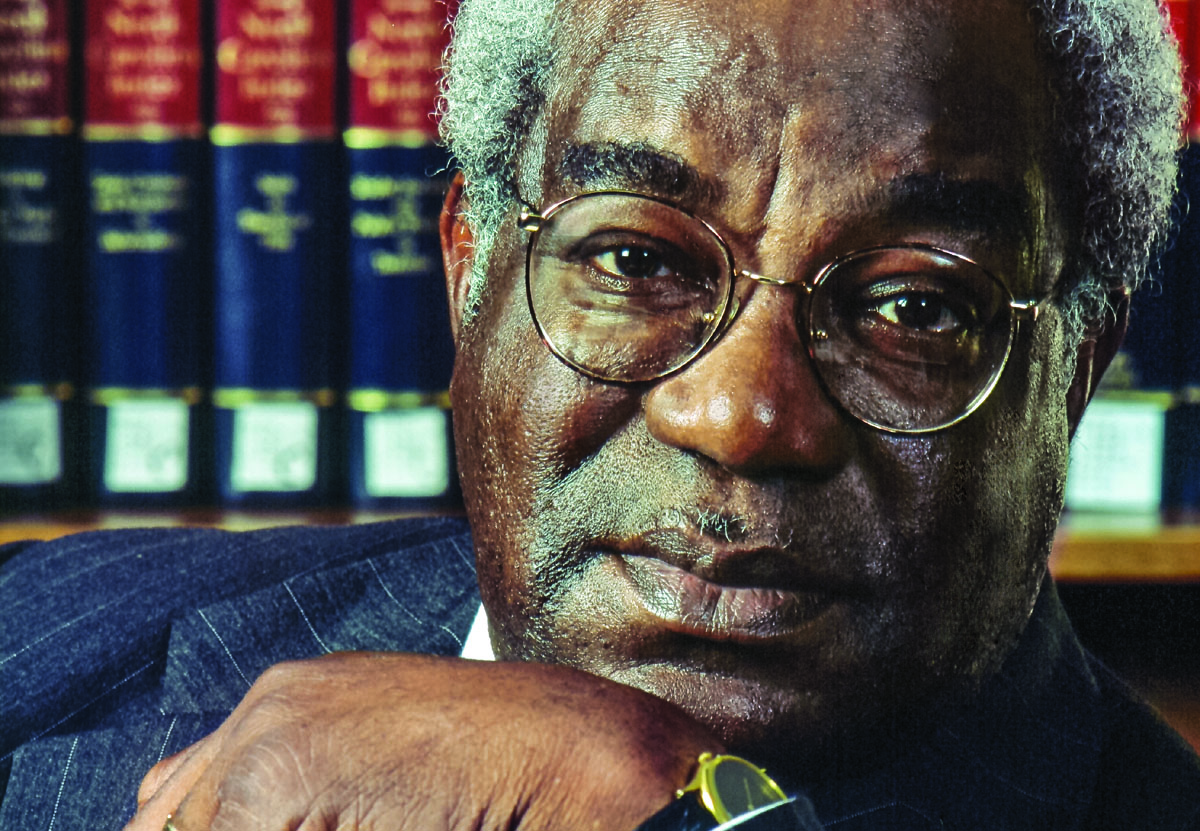

UNC’s civil rights center was founded in 2001 by Julius Chambers ’62 (LLBJD), whose home, office and car were bombed as he pursued school desegregation cases in the 1960s and ’70s. Chambers died in August 2013. (Photo by Dan Sears ’74)

The UNC law school’s Civil Rights Center’s practice of going to court against the state and other government entities as part of teaching law students is inappropriate and should be ended, a committee of the UNC System Board of Governors decided Tuesday.

The 5-1 vote, with one member abstaining, sends the matter to the full board, which could consider it at its Sept. 8 meeting. If the full BOG concurs with the committee, the center could be closed; its director said he doubted it could fulfill its mission if it no longer can hire lawyers to sue the government on behalf of disadvantaged clients.

Ted Shaw, who directs the center, gave a passionate message to the Educational Planning, Policies and Programs Committee prior to the vote in a plea for the center’s mission to train civil rights lawyers, advocate for people who can’t do it for themselves, and work against racial discrimination. And he charged the proposal’s chief advocate, committee member Steven Long ’82, with “an ideological hit — everybody knows why we are here and what the politics are,” Shaw said. “We should not engage in the politics of McCarthyism in the present day.”

Long, speaking for the measure, said, “The state should not hire full-time attorneys to sue itself or its municipalities.”

Gabriel Lugo, chair of the system’s Faculty Assembly, and UNC Chancellor Carol L. Folt reminded the committee that 600 law school deans, faculty and administrators from across the country had signed a letter supporting the center’s work.

Without the center, Folt said, “we would have no other known options for teaching litigation.”

One member who voted for the proposal, Marty Kotis ’91, said that “UNC is the aggressor here” and that he would prefer the University concentrate on teaching its students and not on taking people to court. Long pointed to cases in which the Pitt County school system, sued over alleged resegregation, spent $500,000 worth of textbook money to defend itself against the center’s lawyers. Walter Davenport, a BOG member who is not on the committee, asked: Wouldn’t Pitt logically have had to go up against other attorneys if the Civil Rights Center had not been involved?

The lone vote against the measure came from its chair, Anna Spangler Nelson. She said that action to close the center constituted a “reputational threat” to the Chapel Hill campus and that this was a matter that should be left to the campus.

The center’s lawyers are state employees, but they are paid exclusively with privately raised funds. Established by the late civil rights expert and UNC law school professor Julius Chambers ’62 (LLBJD), it has trained more than 600 students since its founding 16 years ago.

The center first came to the Board of Governors’ attention three years ago in a review of the some 240 centers and institutes at all UNC System campuses. That review resulted in the closing of the UNC Center on Poverty, Work and Opportunity, which was widely seen as a political move by the Republican-dominated board.

The language of the policy says that centers and institutes on the campuses may not engage in litigation. Long made clear he was distinguishing the center from law school clinics, which give students hands-on experience in a variety of legal fields. Such clinics, whose primary work is teaching, would not be banned.

News of the proposed change generated a flood of public comment. Folt said she received 375 letters supporting the center in a single day.

In response to a number of questions from individual BOG members, the center in May issued a 56-page report about its mission written by a committee appointed by Folt and reviewed by Provost James Dean, law school Dean Martin Brinkley ’92 (JD) and others. The committee issued a supplemental report that outlined five alternatives for the center — none of which, it said, could be guaranteed to uphold the center’s mission.

The center’s litigation and related advocacy, the report said, “has deepened its research insights and its national prestige — even as its training simultaneously has provided law students with otherwise unattainable tutelage in how to be conscientious advocates.”

Shaw, who in addition to directing the center is the Julius L. Chambers Distinguished Professor of law, defended the litigation function in an article submitted to The News & Observer, writing that the proposed policy change “is tantamount to saying that law schools cannot teach one of the core functions of lawyering, especially for civil rights and public interest lawyers, by experiential learning.”

As of Tuesday, System President Margaret Spellings had not voiced a position on the center’s future.

At its July meeting, the BOG received a visit from Belle Wheelan, president of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges — UNC’s accreditation agency — who warned the board about micromanaging. Wheelan said the board should stick to making policy and not work directly with the people who run the campuses.

“When boards start micromanaging, you’re stepping out of your lane and it gets my attention,” she said. She warned against meddling in the academic freedom of faculty and against small factions of the board trying to wield too much muscle.

Long said before the Tuesday vote that he saw Wheelan’s words as an affirmation of the BOG’s role.