Confederate Monument Takes Another Controversial Turn

Posted on Dec. 6, 2019 | Updated Jan. 3, 2020

Members of the UNC System Board of Governors who brokered a settlement with the N.C. division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans say they reached the most workable way to keep Silent Sam off campus. (Photo by Jason D. Smith ’94)

The Confederate monument that stood at the University’s front door for 105 years is in the hands of an advocacy group that plans to display it on private property.

Members of the UNC System Board of Governors who brokered a settlement with the group say they reached the most workable way to keep Silent Sam off campus. It includes giving the N.C. division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans up to $2.5 million from the interest on Chapel Hill’s endowment for expenses related to the statue.

UNC administrators were spectators to the settlement, and then-Interim Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz was asking the UNC System for information two weeks after the settlement was reached.

The Faculty Council condemned the payment, social media lit up with dissent and questions, a legal group filed suit to overturn it, and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation said it would not go forward with an anticipated $1.5 million grant. “Our higher-education program worked over the course of 2019 on a significant grant to [the University] to develop a campuswide effort to reckon with UNC’s historic complicity with slavery, Jim Crow segregation and memorialization of the Confederacy,” the foundation said. “On December 2, we decided not to recommend the grant. Our decision was prompted by the university’s announcement that it would give $2.5 million to the Sons of the Confederate Veterans to protect and display the confederate statue known as Silent Sam.”

Students and other members of the campus community on Thursday afternoon marched to the former site of the Confederate memorial to protest the settlement with the Sons of Confederate Veterans. (Grant Halverson ’93)

BOG members were silent for 16 days following announcement of the settlement. Then on Dec. 13, in a regular meeting of the board held by conference call, one member asked for clarification on the limits of use of the money — a leader of the SCV had indicated in a letter to group members that the money might cover a new division headquarters. That prompted another BOG member to ask for more openness with the public and was followed by a statement from the five BOG members who negotiated the settlement.

BOG member Thomas Goolsby ’91 (JD) said the issue “appears to not be dying down but revving up, and it very much concerns me as to what’s been done here. I look forward to all the truth coming out in this and there being open discussion between the board and the press and the people of North Carolina as to what’s happened and what’s actually going on.”

Guskiewicz had asked the same in a Dec. 11 letter to UNC System Interim President Dr. William Roper and BOG Chair Randy Ramsey: “I am particularly concerned with recently published postsettlement comments from the SCV regarding how the organization may seek to use funds from the charitable trust, including plans to promote an unsupportable understanding of history that is at odds with well-sourced, factual, and accurate accounts of responsible scholars,” Guskiewicz wrote.

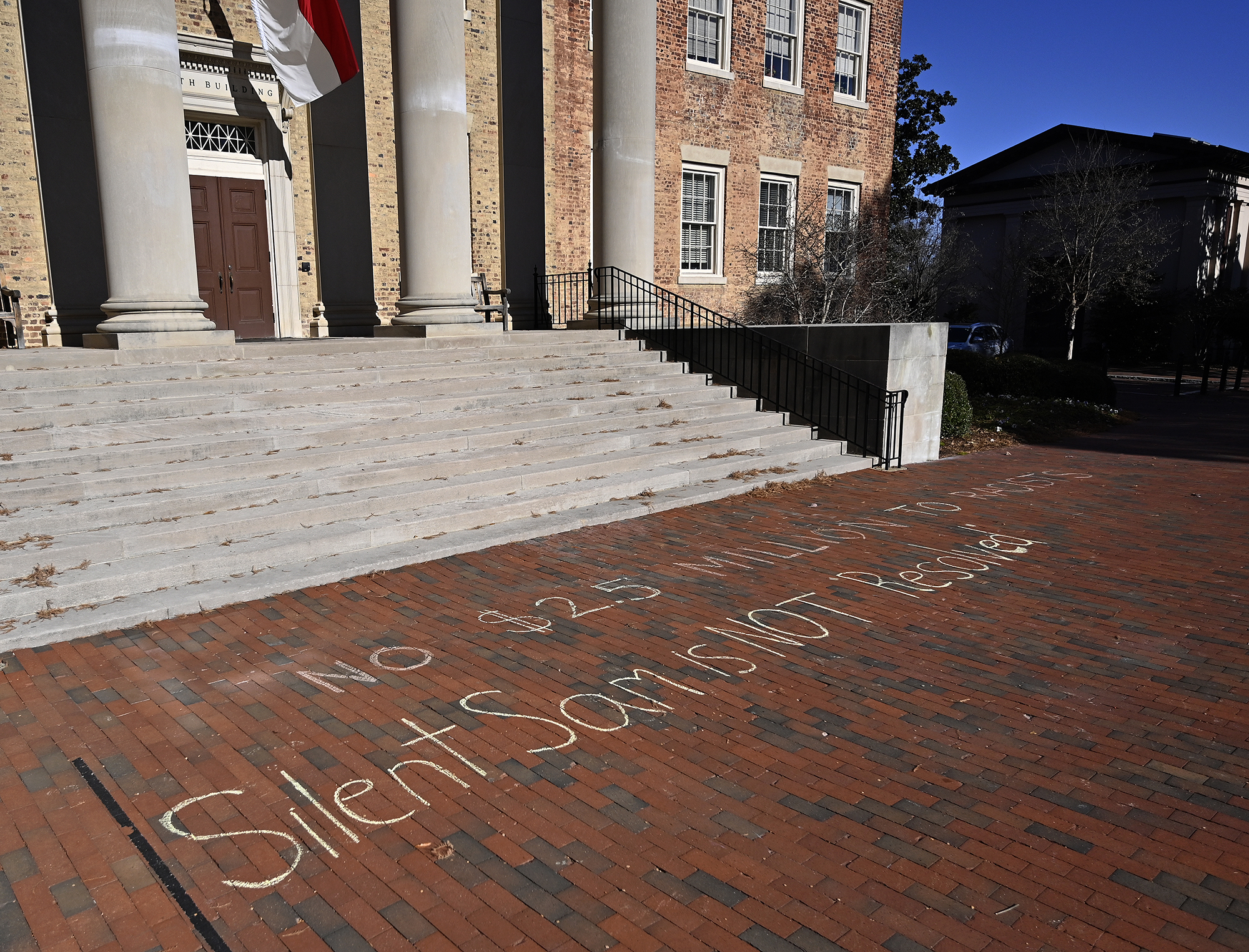

Protesters expressed their anger with the financial settlement with a chalk message in front of South Building. (Grant Halverson ’93)

“These comments, along with various aspects of the settlement, particularly the requirement that UNC-Chapel Hill reimburse the UNC System for the payment of the funds to the trust, have led to concerns and opposition from many corners of our campus.”

On Dec. 16, the UNC System released documents in response to public records requests. Matthew McGonagle of the law firm Narron Wenzel was named as the trustee to administer the settlement. The monument trust states that the money can be used for property acquisition; utilities, repair and maintenance; transportation of the statue; security; and legal and financial fees, “without intending to limit the discretionary authority of the trustee.”

Guskiewicz’s stand against the statue returning to campus was a factor in his selection as interim chancellor a year ago. But the disposition of the issue caused some to question South Building’s commitment to healing the racial divisions that have spilled out of it.

“It’s good to get [Silent Sam] off campus, but it’s bad because it sends a message that seems to be University support for these white supremacists, and that poses further threats to the safety of the people on campus,” said Larry Grossberg, interim director of graduate studies and a professor of communication studies and cultural studies, in an anger-filled meeting of the chancellor’s new commission on campus safety. “There are bigger issues here that are not about safety … but about trust in the administration more broadly.”

In the same meeting, De’Ivyion Drew, a sophomore and party to the suit that aims to overturn the settlement, said the financial payout is “way worse” than the relocation of the monument.

“There’s a lack of perspective from a person of color, particularly black people, who would prefer to have the statue back up than to have the Sons of Confederates or any white supremacy group get $2.5 million,” she said.

At the reception announcing Guskiewicz as chancellor, student body President Ashton Martin, who had been on the chancellor search committee, devoted almost all her remarks to the issue.

“Silent Sam may be gone, but the feelings and sentiments associated with it remain prevalent both on campus and in the minds of students everywhere,” Martin said. “Chancellor Guskiewicz, you now bear the responsibility for making sense of this situation. In order to do this, we want you to confront UNC’s history and acknowledge the wrongs committed in the name of the Confederacy and furthering a racist agenda with the settlement. We want to see you take an active stance against the sentiments of racism, hate and suppression that have taken up space on our campus for far too long.”

Guskiewicz replied: “I hear you along with the voices of many on our campus. We do have work to do.” He announced he was establishing a commission to confront the issue and funding it with $5 million.

In early 2019, five members of the UNC System Board of Governors — Darrell Allison ’99 (JD), Holmes, Wendy Murphy, Anna Spangler Nelson and Bob Rucho — were tasked to work with the University to find a solution for the monument that would be safe and compliant with the law.

A host of legal experts have questioned the validity of the process that ensued.

The future of the statue, which was pulled down by protesters in August 2018 and its pedestal removed by executive order in January 2019, appears to have been settled before a consent judgment actually was filed. The BOG committee met in private at 10 a.m. on Nov. 27, the day before Thanksgiving, having called the meeting two days earlier. The filing time stamp on the judgment by Judge Allen Baddour ’93 (’97 JD) in N.C. Superior Court in Hillsborough is 11:10 a.m. that day. The UNC System office reported the judgment in a news release that afternoon.

Roper signed the judgment on Nov. 26, and Ramsey signed it on Nov. 22.

The SCV asserted in its complaint that the Daughters of the Confederacy had requested two days after the statue was toppled that it be returned to UDC and that the UNC System had failed to do so.

A state law enacted in 2015 prohibits removal of historic monuments on public property. The complaint said that when the UNC System failed to restore the statue to its original location on campus within 90 days of its removal, as specified in the law, ownership reverted to UDC.

The SCV complaint asked that the monument be restored to its site in McCorkle Place and that, “in the alternative,” it become the property of the SCV, to which UDC handed over all rights, title and interests prior to the judgment.

More than 200 students, faculty and other members of the campus community marched on Thursday to protest the settlement over the Confederate monument known as Silent Sam. (Grant Halverson ’93)

A terse UNC System statement noted that the money paid to the SCV “may only be used for certain limited expenses related to the care and preservation of the monument, including potentially a facility to house and display the monument.”

SCV leader Kevin Stone appeared to contradict the word “limited” when he wrote to his members that the SCV had received rights to “perpetual care of Silent Sam and the purchase of land on which to prominently display him, to build a small museum for the public, and to build a comprehensive Division headquarters for the benefit of the membership.” In his letter, Stone said the group had been trying to have the statue restored to its location or turned over to the SCV since shortly after it was taken down. Stone said that earlier in 2019 the BOG approached the group “and wanted to open negotiations,” which he said went on “for many months.”

“Our biggest advantage was the extremely adverse publicity they were receiving,” the letter said. “They heard we were preparing to file a suit. … While they were not at all worried about losing, the prospect of another media circus on campus really had them worried, especially given that they have a hostile faculty at UNC and a very nervous donor pool that shies away from any controversy. They suggested that we try to reach a solution for Silent Sam via the legislature and get the House and Senate to sign off on a deal that would satisfy the law, us, and UNC.”

Among the documents released Dec. 16 was a letter from Stone, who acknowledged and apologized for expressing personal bluster in the days after the settlement was reached.

Writing to BOG member Holmes, Stone also said: “The SCV is not a white supremacy group and just because some people who disagree with us call us that does not make us one.

“Ultimately, once you get past the howling and indignation, SCV and UNC were able to do what people should do. Despite our differences our groups found common ground and found a solution to the problem. Our two groups did not let the perfect be the enemy of the good.”

Stone said that the group had become convinced it could not win a lawsuit against the University or the UNC System. At one point, the group proposed changes that would strengthen the 2015 historic monuments law in exchange for being given possession of Silent Sam; that did not clear the N.C. Senate, Stone said.

SCV filed suit expecting it would not be successful, he said. “Our legal action has immediately met with an offer from them to settle.”

The agreement stipulated that the statue cannot be displayed in any county that is home to one of the 17 UNC System campuses. That includes the state’s largest counties — Mecklenburg, Wake, Guilford, Durham, Forsyth, Buncombe and New Hanover — as well as Orange. That part of the settlement has not raised many complaints. Most of the rest of it has.

Assistant history professor William Sturkey wrote in a New York Times opinion piece: “Our administrators have repeatedly rejected scholarly efforts to uncover [UNC’s racial] history, claiming a shortage of funds. So it is especially galling to see the board give $2.5 million to a neo-Confederate organization. It is the clear endorsement of a discredited and dangerous idea.”

Anne Whisnant ’91 (MA, ’97 PhD), former top assistant to the secretary of the faculty and now an adjunct history professor, asked Sturkey’s class on the last day of classes: “What is the University committed to in its mission? There’s been hypocrisy at times that’s been breathtaking. … The University’s soul is at stake here.” Whisnant said she would like to see top administrators “take bold stands” on the race issue — “risk their jobs to do what’s right.”

In an opinion piece for The News & Observer, the five BOG members who worked on the disposition defended their work. “While we have heard from citizens from across this state who have expressed their gratitude for our efforts of finding a solution to this issue, we also acknowledge that others strongly disagree with the board’s decision to approve a settlement,” it said. “Compromise was a necessity.

“However, we remain convinced that our approach offered a lawful and lasting path that ensures the monument never returns to campus.”

Members of UNC’s Faculty Council took the opposite view. In a tense meeting Dec. 6 that crackled with criticism of the administration, the council passed a resolution that read: “While we continue to support the permanent removal of the confederate monument known as Silent Sam from campus, we condemn the settlement that gives the statue and $2.5 million to the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Such a settlement supports white supremacist activity and therefore violates the university’s mission as well as its obligations to the state.”

Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights, based in Carrboro, filed a motion on behalf of six UNC students and one faculty member to intervene in the lawsuit that spawned the settlement, asking that the judgment be reopened and the payment to the SCV overturned.

N.C. Attorney General Josh Stein said that he found nothing legally wrong with the proceedings but that he “personally believes it is an excessive amount of money that should instead be used to strengthen the university and support students.” His office said it was not involved in negotiating the settlement.

As the Alumni Review reported in 1913 when the statue was erected, the United Daughters of the Confederacy intended the monument to be “in memory of all University students, living and dead, who served in the Confederacy.”

The monument’s presence made some people and groups unhappy at intervals since the 1950s. The outcry against its continued presence grew louder in the past 10 years. An organization of students and others called the Real Silent Sam Coalition emerged in about 2011, calling the statue offensive to people of color and at first suggesting UNC erect a reinterpretation plaque to explain it.

Some students said they were insulted by its presence; they called it a symbol of the Confederacy’s loyalty to the institution of slavery. Some added that they did not feel safe when counterprotesters came to campus.

Others saw Silent Sam as a tribute to those who fought for their homeland in the Civil War, perhaps without regard to the slavery issue. Many said that removing the statue would be detrimental to the understanding of history.

In spring 2015, the trustees agreed to rename a building that honored a Reconstruction-era Ku Klux Klan leader. Changing Saunders Hall to Carolina Hall came with a 16-year moratorium on other renamings on a campus with a number of buildings named for people who were involved with white supremacy.

That fall, then-Chancellor Carol L. Folt appointed a task force to carry out the UNC trustees’ directive that the University open a dialogue on its racial history. The task force worked without a budget but was funded from the chancellor’s office as needed; its work essentially was paused after the Confederate monument was pulled down by protesters a year after Charlottesville’s Unite the Right rally.

On Dec. 13, in his first act as chancellor, Guskiewicz committed $5 million toward UNC’s History, Race and a Way Forward Commission.

After protesters knocked down the statue, UNC’s trustees and administrators worked for months on a viable new location for it. They agreed in December 2018 to a plan to move the monument to what would have been a new building in the former Odum Village on the southern edge of campus; it was estimated to cost $5.3 million to build, $800,000 a year to maintain and would house a center for exhibits and education on UNC’s history. Folt and several trustees made clear that their preference would be to not have the statue on campus, but they said they were convinced that would be a violation of the 2015 law.

The BOG rejected the proposal, citing safety and the estimated cost. They directed the trustees, chancellor and top administrators to work with a BOG task force to find another solution by March 15. Delays persisted, and the BOG omitted the issue for discussion at its fall 2019 meetings.

Folt ordered the statue’s base and commemorative plaques removed as she announced her resignation in January 2019.

On campus, opposition to keeping Silent Sam continued. Hundreds of faculty and students signed letters; athletes and alumni who play or had played in the National Basketball Association registered protests; the Odum Institute — named, as is Odum Village, for the social scientist and vocal anti-racism activist Howard Odum — said the statue was an affront to his legacy.

Library administrators pleaded that the statue not be placed in any UNC library; few practical locations were left. Fifty-four African American faculty members signed a letter that read in part: “In 1913, the Confederate monument did not stand in opposition to the stated values and mission of the University. In 2018, it most certainly does. … A monument to white supremacy, steeped in a history of violence against Black people, and that continues to attract white supremacists, creates a racially hostile work environment and diminishes the University’s reputation worldwide.”

Rallies at UNC grew angrier about the time of the building name change. But protests featuring anti-Silent Sam protesters and supporters of Confederate groups boiled over — sometimes becoming violent — after the statue was pulled down. Police were criticized for the handling of a September 2018 rally at the site of the monument and of a December 2018 street march held a few weeks before the statue’s base was ordered removed.

The campus continued to attract unwanted outside attention. In March, members of an outside group with ties to the pro-Confederate counterprotests were caught carrying guns on campus. Later that month, two people were apprehended in the act of defacing a monument to the people of color who built the original campus.

— David E. Brown ’75

Timeline: Silent Sam and Related Issues

Calls for removal of the statue — and rallies for its support — have occurred periodically for decades.

1908 Trustees approve erection of a monument by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in memory of UNC students who joined the Civil War effort. 1913 Dedication of what was then called the Soldiers’ monument includes a speech by Confederate veteran, trustee and industrialist Julian S. Carr (class of 1866) that includes an account of having “horse-whipped a negro wench” near the site, because “she had publicly insulted and maligned a Southern lady.” 1954 Apparently first use of the name Silent Sam, in The Daily Tar Heel, due to the fact the soldier carried no ammunition. 1965 A letter appears in The DTH that asks whether the statue is a racist symbol that should be removed. 1968 Graffiti appears on Silent Sam at the time of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. 1971 and again in 1973, UNC’s Black Student Movement holds protests at the statue after the deaths of black men killed by a motorcycle gang and by police. 1992 Silent Sam is the site chosen for Chancellor Paul Hardin and others to speak to students about the controversial beating of Rodney King by the Los Angeles police and the issue of whether UNC should erect a freestanding Black Cultural Center. 2000 February: Gerald Horne, then director of UNC’s Black Cultural Center, writes a newspaper column in which he likens the statue to a Confederate battle flag and says it was hypocrisy and slavery denial for UNC to leave it standing. 2011 September: Members of the Real Silent Sam Coalition hold a protest at the statue, calling it offensive and suggesting UNC erect a reinterpretation plaque to explain it. 2015 January: Students lead a large, angry rally around Silent Sam, demand the renaming of Saunders Hall for author and activist Zora Neale Hurston. April: UNC trustees hold a special meeting to hear comments on the name-change issue. May: Trustees vote 10-3 to change Saunders to Carolina Hall, approve a 16-year moratorium on other renamings and order “curating” of UNC’s racial history. July: Vandals deface Silent Sam, painting “KKK” and “murderer.” N.C. General Assembly enacts a law prohibiting removal of any publicly sited “monument of remembrance.” September: Chancellor Carol L. Folt announces a task force to carry out the trustees’ directives. November: Students of color speak out at a large rally outside South Building in the aftermath of racial unrest at the University of Missouri; a week later, a town hall meeting fills Memorial Hall, where students present a long list of demands. 2016 January: Chancellor Folt meets with leaders of the movement, who amplify demands; later she reports to the campus on required racial sensitivity training for administrators and a dedicated gathering place for black students, and she promises results of a survey on diversity. November: Carolina Hall lobby display is unveiled. 2017 August: UNC Police erect two concentric circles of steel barricades around Silent Sam in anticipation of a protest rally that evening, amid talk that the statue might be taken down. Gov. Roy Cooper ’79 (’82 JD) tells UNC officials they can take it down in the event of an imminent threat to public safety and security. UNC attorneys decide not to challenge the law. November: Trustees hold a listening session on Silent Sam — 28 people speak, two of whom support keeping the statue. Folt says: “I’d like to reiterate that, if I had the authority, in the interest of public safety, I would remove the monument to a safer location on our campus, where we could preserve, protect and teach from it. What I heard yesterday reinforced that belief.” A campus police officer goes undercover at the statue to engage both sides in conversation. 2018 May: Graduate student Maya Little throws red ink and what she says was her own blood on Silent Sam in full view of the police assigned to protect it and is arrested. July: UNC reports it spent about $390,000 to provide police security for Silent Sam, July 2017 through June 2018. Aug. 20: A Franklin Street protest is a diversion for an organized offensive on the statue, and protesters pull it off its pedestal, igniting a response marked by jubilation and by angry street confrontations. Aug. 25: A group of Confederate monument supporters clashes just off Franklin Street with those supporting removal. Aug. 28: Board of Governors passes a resolution directing Folt and the trustees to come up with a “lawful and lasting” plan to preserve the monument with attention to safety, and it sets a Nov. 15 deadline. Aug. 31: As of this date, a total of 17 people had been arrested related to three protest events; of those, 16 were not affiliated with the University. December: UNC announces it will ask for the Board of Governors’ approval to build a $5.3 million Center for History and Education, where Silent Sam would be on display indoors. In mid-month, the Board of Governors rejected that proposal and set up a five-member task force of its members to work with trustees, the chancellor and UNC’s top administrative staff to come up with another plan for Silent Sam by March 15. 2019 March: BOG extends the deadline to May. April: BOG Chair Harry Smith tells a news conference he thinks restoring Silent Sam to its original site is “not the right path,” a reversal of Smith’s previous stance. May: Indefinite delay announced for the disposition decision. November: The statue is given to the Sons of Confederate Veterans in an agreement approved by the Board of Governors.

More:

• Comprehensive coverage of Silent Sam from the Carolina Alumni Review archives.