“Some Things That Are Just Wrong”

Posted on Nov. 11, 2019

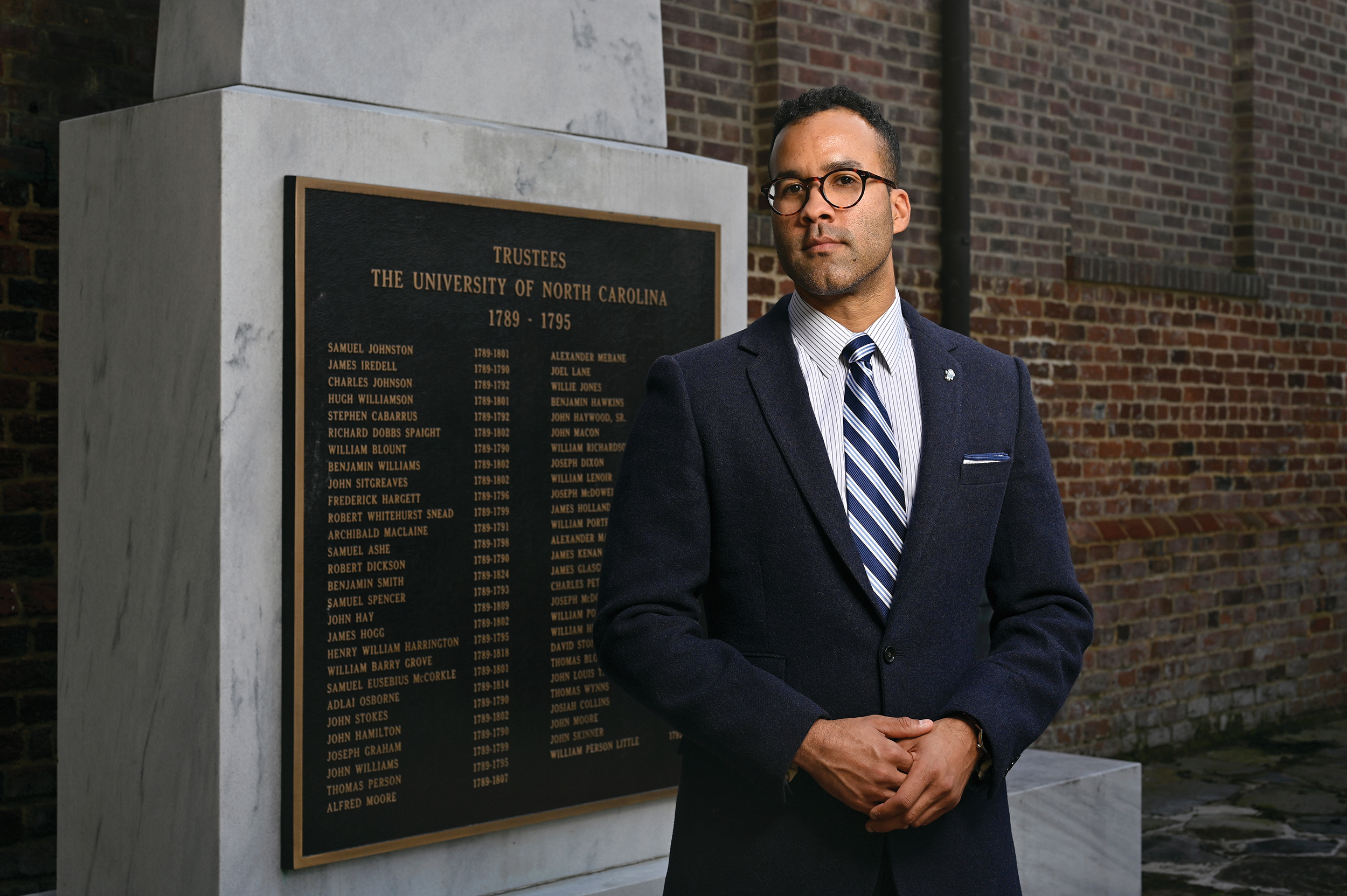

What, professor William Sturkey asked, has UNC done and left undone toward a public reckoning with its racial history following events that turned the campus into a focal point on a simmering national issue five years ago? (Grant Halverson ’93)

Somewhere between 30 and 600 people died in 1898 in the Wilmington insurrection/race riot/massacre — it’s been called all three by different people at different times. It’s also been called the only successful coup d’etat in American history.

It began when leaders of what was then the state’s Democratic Party spurred a mob to harass and kill black people, destroy their businesses and annihilate the elected Fusionist government in which blacks were active. And it created a turning point in Reconstruction in the state.

But for most of the 20th century, it was not taught or widely known. It wasn’t that the information wasn’t available. “We have chosen not to read it,” said a student this fall in William Sturkey’s history class. “We have chosen not to remember it.”

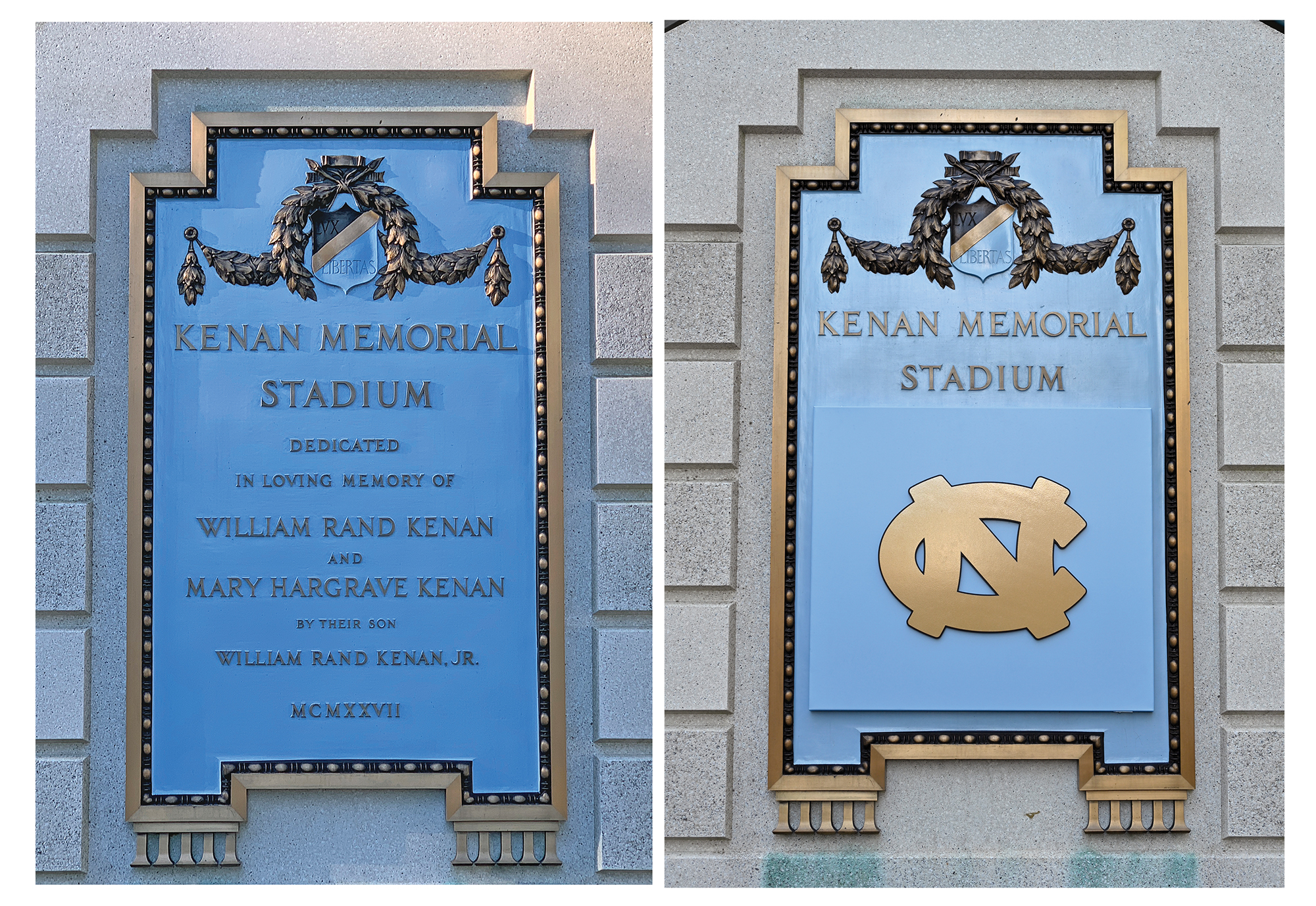

That’s the point of “Race and Memory at UNC,” the class Sturkey spent several months this year shaping to help kick off the University’s shared learning initiative, “Reckoning: Race, Memory and Reimagining the Public University.” The student’s comment came in a session devoted to discussing the role of William Rand Kenan Sr. (class of 1864) in the Wilmington event. Kenan was the leader of a Gatling gun squad that fired on black people and their property. On Sept. 28, 2018, The Daily Tar Heel published a front-page report under the headline: “Kenan Memorial Stadium: racism and white supremacy are hidden beyond a dedication plaque.” Within a week, then-Chancellor Carol L. Folt announced that UNC would refocus the dedication of Kenan Memorial Stadium from Kenan Sr. to William Rand Kenan Jr. (class of 1894), who built the stadium and dedicated it to his parents in 1927. The DTH’s Oct. 3 headline read: “Folt announces recontextualization of Kenan Memorial Stadium.”

A plaque in the northeast corner of the stadium that detailed Kenan Sr. as the dedicatee was still in place until mid-October, when it was covered over.(Grant Halverson ’93)

Though a plaque in the northeast corner of the stadium that detailed Kenan Sr.’s business empire has been removed, the original at the main north gate designating him as the dedicatee was still in place until mid-October, when it was covered over.

Sturkey’s pass/fail class is built around a long list of guest speakers, two each week, and offers one hour of credit. Before the start of the semester, Sturkey encouraged local alumni to audit the class.

The professor concurred with his student: History is not necessarily what happened, he said, “it’s what gets written down.”

This was part of the larger question of the day’s lesson. What, Sturkey asked, has UNC done and left undone toward a public reckoning with its racial history following events surrounding the renaming of Saunders Hall as well as involving Silent Sam — events that turned the campus into a focal point on a simmering national issue five years ago?

Sturkey is an assistant professor of history who came to UNC in 2013 and has become immersed in the reckoning. The Review asked him for his thoughts on what we “choose” to make history.

Discuss the genesis of your class.

“It really began in the wake of the Silent Sam explosion of August 2017, and I think a lot of us in the history department really came to realize that Silent Sam was just the tip of the iceberg and that the conversations people were having were often around … many other issues, like slavery, for example, and so I think a lot of people realized we need to do the full history and we need to teach it in order to empower students and our community.

“It’s a new class … I think a lot of the reckoning initiative courses were just existing courses on race, and this is one that’s designed specifically for the reckoning initiative. It’s also by far the largest class in the reckoning initiative [reckoning.unc.edu lists 18 courses]. I think there are roughly 800 students total taking courses in this reckoning initiative, and over 100 of them are in this class.”

Along the northeast concourse of the stadium were three plaques: one about the growth and development of the arena; one about Charlie Loudermilk ’50, for whom the athletics academics center is named; and one about Kenan Sr.’s career. Sturkey was unhappy with that one; he told his class, “Their fortune came from 19th-century slavery.”

When Sturkey served on the Faculty Athletics Committee, he brought this up and the committee agreed to ask that a “truth” plaque be added. The plaque was removed instead. Sturkey was asked what he thought about the dedication plaque remaining in place for as long as it did.

“I don’t think it’s a solid premise to say that an entire generation of a family is not going to have a relationship with this institution that they have a very long relationship with because something was exposed about one particular man.

“One of the things that’s important is you can move through this campus landscape and appreciate its beauty and have no idea of all the ghosts. There were black people all over the record; they’re everywhere from the stone walls that we cherish to South Building; there were living people that built all that stuff, and you would never know about it. And I think it’s appropriate in this day and age to recognize that they existed.

“[O]ne of the things I really wanted to get students a sense of is that we’re not reinventing the wheel — we’re just teaching this history in a much more transparent way, in a much more productive and honest way, I think. We’re free of some of the political considerations that have limited the way UNC has been able to study and disseminate its history over the last few years.”

“The University is susceptible to any of these skeletons rearing their heads if they’re not able to marshal the resources to know about them in advance and do something.”

Sturkey is unapologetic in his criticism of the Folt administration’s handling of the Board of Trustees’ 2015 order to add signs and displays on the campus to tell UNC’s racial history and to otherwise “curate” the subject publicly. He said other universities — among them Virginia, William and Mary, and Georgetown — “are light years ahead of us … in terms of the outward-facing nature of their program to study the issue of slavery.”

“I don’t think it did come from the top, but I do think if you’re paying attention that there was a general silencing of people in South Building. If you look at Carol Folt’s administration for two years, hardly anybody out of that building said a peep — and those that did are now gone. These are smart people that have opinions and are very experienced and have been here a long time, in some cases. It’s weird that none of them ever said anything, but that created a vacuum where all these other people were able to step in with whatever agenda or perspective they had — that created a vacuum where UNC lost control of the narrative very, very quickly.

“We [in the history department] have people who are paid to be experts about specific topics, and at the time when their expertise was needed the most, they were essentially ignored, in some cases.

“Our institution and our approach to historic memory is so rife with all these political games that infest our governing bodies that it’s hard to imagine somebody being completely free of all those politics that have seemed to bog us down for the last few years. So one idea is to bring in somebody who could research and work independently from all of those constraints. Or … we could have people come in and do sort of a peer review of whatever we come up with. And that makes total sense, because that’s how scholarship is produced anyway. If we want to do this right, that might be a good path.

“Things have been done, but they are not as public and outward-facing or transparent as this class — one of the things I really wanted to get students a sense of is that we’re not reinventing the wheel — we’re just teaching this history in a much more transparent way, in a much more productive and honest way, I think. We’re free of some of the political considerations that have limited the way UNC has been able to study and disseminate its history over the last few years.”

In your comments on the Kenan family history to your class, you were strikingly opinionated, in a time when we’re told academics have to walk on eggshells in these discussions.

“The thing about teaching the history of race in the South that we struggle with sometimes is this lack of moral clarity that I was talking about yesterday. To me as a historian, this is true in my research and in all of my teaching. Look — there are some things that are just wrong. So there are some different areas here in the class where I might take for granted that slavery was wrong, that racial violence was wrong, that Jim Crow was just morally wrong. But look — from my perspective, that’s just the fundamental truth.

“I didn’t go looking for race and racial history — it found me.”

“And the way that I craft that argument — how could I possibly have any other opinion? And a big part of this is my own identity, and I realize that, but in understanding the history of this place, that’s a huge part of it. The people that have shaped the history, it has not been a very diverse group of folks, like the namesake of this building, for example [J.G. deRoulhac Hamilton, chair of the history department from 1908 to 1930, one of the builders of UNC’s prestigious study of the region, who argued that the Ku Klux Klan protected North Carolina from corrupt blacks and carpetbaggers during Reconstruction]. They had a racial agenda that was in some ways the opposite of mine.”

What is the outcome you’re after or that the University should be after? (Sturkey said, for instance, that the history department currently is raising money to hire a professor who specializes in American slavery.)

“If we do all the hard stuff, what do we get? I’ve got to say I don’t always fully understand that. … [Y]ou know when you do things that are challenging you should be making some people uncomfortable. There should be people who want to stop what you’re doing. But then you look at the young people, and it’s just, at the end of the day, this idea that there’s gonna be a time in this country, maybe, where we’re not bogged down by race in the way that we have been for over five centuries now, and it’s devastating to me to think of my grandchildren having the same argument 100 years from now that people have been having for the past 200 years.

“At some point we’ve got to get beyond this, and we’ve got to get more free of it than we ever have been. And I think something particularly about me that’s not particular to race — but that’s actually age [Sturkey is 37] — is that I’m the first person in my family on my dad’s side to ever be born outside of the Jim Crow-era South; whatever he learned about being black in Arkansas when he was 5 years old, that never infected me. I think in some ways my generation and subsequent generations are gonna be more free of that than anybody that ever came before us.

“And I think that’s part of why it should be young folks who are pushing this forward. I didn’t go looking for race and racial history — it found me. My high school [in Pennsylvania] was just race all the time. It was very stressful being black in some classes because it just came up constantly. One time I sat down and I counted all the ways that people made new adverbs out of the word ‘nigger,’ and I got to, like, 41, and it was just all the time every day.”

— David E. Brown ’75

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.