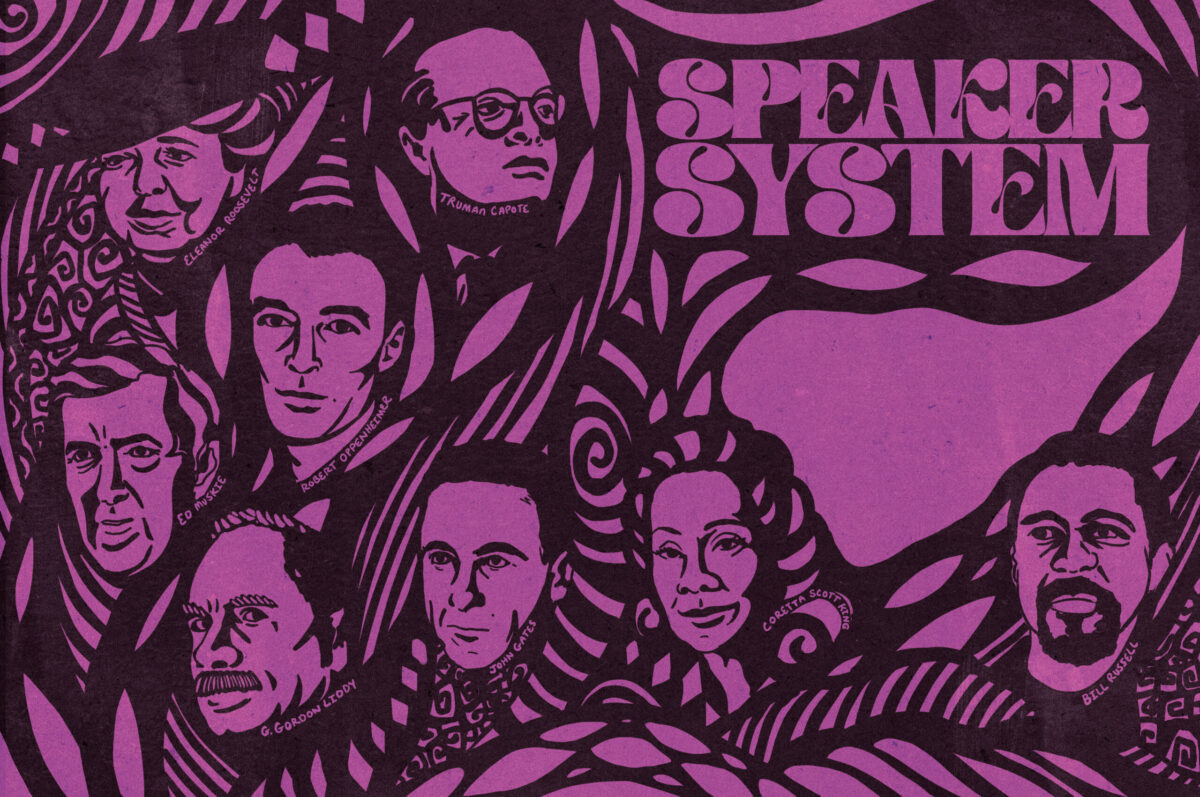

Speaker System

Posted on July 24, 2024For decades, the student-led Carolina Forum invited to campus some of the most controversial social and political figures of the mid- to late-20th century — and the forum’s president was considered one of the most powerful student positions.

by Janine Latus

(Illustration: Carolina Alumni/ Haley Hodges ’19)

In September 1975, Elton Hyder III ’76 drove his green 1973 Porsche 914 east on Highway 54 to Raleigh-Durham Airport, its sole terminal so small that the baggage claim was outside. The senior English major at Carolina was looking for NBA basketball legend Bill Russell. It was a pleasant 70-degree day, but Hyder doesn’t recall whether he had removed the car’s targa top to accommodate Russell’s 6-foot-10-inch frame. What he remembers clearly, however, is Russell, then coach of the NBA’s Seattle Supersonics, speaking to a packed Memorial Hall not just about professional basketball but about race relations, drugs and growing up Black in Boston.

“We are all in this together, so what happens to me happens to you,” Russell told the audience, according to an article published Sept. 18, 1975, in The Daily Tar Heel. “We can’t live in a vacuum, so we have to learn to live together.”

Hyder, now a business investor who lives in Virginia and Texas, was president of the Carolina Forum, established in 1948 to bring to campus “the best minds in the world,” according to the Carolina Forum webpage. In the summer of 1975, Hyder had sent out invitations, negotiated with agents and assembled a speaker schedule that included some of the biggest names in the literary, journalism, political and sports worlds. He and about a dozen other students spent the school year hanging promotional posters, chauffeuring speakers and juggling event logistics.

The speakers the forum managed to land were icons of the time: literary celebrity Truman Capote, author of In Cold Blood; George Plimpton, the sports and literary journalist who pitted himself against professionals in hockey, baseball and boxing, sharing his experiences in books, movies and television appearances; author Tom Wolfe, famous at the time for his chronicling the hippie movement in The Electric Kool Aid Acid Test; and Jeffrey MacNelly ’69, a two-time Pulitzer prize-winning political cartoonist.

As president, Hyder had the privilege of spending individual time with the celebrities and social activists, learning about their views and personal life. Hyder said MacNelly told him he dropped out of Carolina because he always doodled during class and didn’t pay attention to the lectures. With Russell, Hyder said he had a two-and-a-half-hour dinner, during which Hyder mostly asked Russell about his basketball career. “I didn’t ask him about social issues, and I regret that now,” he said.

From Roosevelt to Hefner

The Carolina Forum was founded as an offshoot of the Carolina Political Union, a nonpartisan group that didn’t shy away from inviting controversial speakers such as leaders of the Communist Party and the Ku Klux Klan. The political union and the forum brought to campus some of the greatest American influencers, including Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, New York Gov. Avril Harriman and Gen. Omar Bradley. Later, the forum hosted physicist and father of the atomic bomb Robert Oppenheimer, civil rights supporter Rep. Sam Rayburn, economist John Kenneth Galbraith and Playboy magazine founder Hugh Hefner. The speakers were selected to appeal to the general student body, and each year the focus shifted depending on the cultural zeitgeist and the interests of the committee running the forum.

Hyder joined the forum because he considered its presidency, along with the size of the forum’s budget and the influence it had on campus, the third most powerful position at Carolina. Only the president of the student body and the editor of The DTH wielded more influence among students, he said.

The forum didn’t have physical offices, and its annual budget was $30,000 — equivalent to about $180,000 today. Neither the University nor a faculty member dictated how to spend it, an arrangement for a student-led group, Hyder noted, that is hard to imagine on today’s campus. The forum, like other Carolina Union committees, was overseen by Howard Henry, the head of the student union and who Hyder said was a great mentor.

Hyder’s tenure followed a decade of turmoil and controversy on campuses nationwide, and he speculated faculty may have thought they no longer knew how to manage students. “Maybe that’s what led to a public university like North Carolina giving students significant funds and saying, ‘You all figure it out,’ ” he said.

Early on, the forum was embroiled in controversy. The group invited John Gates, editor of the communist newspaper the Daily Worker, to speak in January 1949 about his and 11 other Communist Party board members’ indictments to overthrow the United States government. When Gates arrived on campus, then-chancellor Robert House (class of 1916) told Gates he was not welcome because a North Carolina statute prohibited a person advocating or teaching the overthrow of the United States or North Carolina governments from speaking in a state-owned building.

Gates later spoke to about 1,000 people gathered in front of Chapel Hill High School on West Franklin Street, where the school was located at the time. Gates argued that the state law barring him from speaking in a public building was “a bad law, but I won’t argue it now,” according to The DTH. He told the crowd of students, some of whom booed and heckled him, that they were “showing a spirit [for free speech] that is lacking in some of the University officials.”

What followed was a flurry of letters in The DTH. “I was shocked when I learned of the University’s trampling on our rights of free speech and assembly supposedly guaranteed by the Constitution,” wrote Jack Hopkins ’51.

J.R. Cherry ’50 took the opposing view. “Orchids to Chancellor House for invoking one of the most intelligent statutes ever to emanate from an assembly of lawmakers,” he wrote.

In 1963, the N.C. General Assembly passed An Act to Regulate Visiting Speakers at State Supported Colleges and Universities — commonly called the Speaker Ban Law. The measure prohibited from speaking at a state-supported college campus anyone who was a known member of the Communist Party or had invoked the Fifth Amendment when asked whether he or she had communist or subversive connections, among other restrictions. The next year, the forum invited Marxist historian and Communist Party member Herbert Aptheker but then withdrew the invitation.

“It is my own opinion … that it would be the height of folly to set up another situation, such as the Gates incident for the Communists,” Institute of Government Director John Sanders ’50 (’54 JD) wrote in a letter. “Such results as those of the fiasco of last January could only react to the discredit of the University, of the student body, of the forum, and of the whole democratic system which we seek in our own small way to protect and advance, should we again knowingly bring down upon our heads the criticism of groups ranging in prestige from the student legislature to the United States Senate, with the consequent reaction on the part of those people of authority in the state who are not loath to attack the University.”

Three years later, in 1966, the leftist activist group Students for a Democratic Society, the YMCA, The DTH and the Carolina Forum invited Aptheker and Frank Wilkinson, who had refused to answer questions from the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee about his political affiliations stating it would violate his constitutional rights, to come speak on campus within a week of each other. Both were banned from UNC. Students escorted Wilkinson around campus to several places to speak, but security denied him access to buildigs to address students. He finally spoke to what Chapel Hill police estmated to be a crowd of 1,200 students while standing on the sidewalk adjacent to the north stone wall of McCorkle Place, just a few feet off campus property. (“Putting Ideas in Their Heads,” November/December 2011 Review.)

“A lot of people didn’t realize that the law made the point that anyone who had ever pled the Fifth Amendment was bad,” George Nicholson III ’66, president of the Carolina Forum at the time, told the Review in 2011. “Our point was that it affected more than just Communists. Anyone who was exercising their constitutional rights was banned.” (Wilkinson pleaded the First Amendment, not the Fifth, and served time in federal prison for contempt of Congress.)

Nicholson and 11 other students filed suit against the University, and in 1968, a three-judge panel of a federal Circuit Court ruled the Speaker Ban Law unconstitutional. A plaque commemorating the action is attached to the stone wall where Wilkinson and Aptheker spoke.

Nicholson’s tenure as president of the forum was filled with controversy. Two months before Wilkinson and Aptheker spoke, in December 1965, the Carolina Forum invited Rep. Charles Weltner, a Georgia congressman who had called for the investigation of the KKK and had planned to speak on “the invisible empire.” A klan spokesman contacted Nicholson a few days before the speech asking if they could have 50 to 60 seats reserved in Memorial Hall so KKK members from around the state could attend the event. “I want to take this opportunity of reiterating that all forum programs have been and will continue to be open to the public,” Nicholson told The DTH. “We have no intention of barring anyone as long as they conduct themselves in an orderly fashion.” One member of the KKK attended, and the event proceeded without issues.

Boundaries pushed

In 1970, corresponding with the first Earth Day, the nation’s attention was on leaders of the environmental movement, including pollution control advocate Sen. Ed Muskie of Maine and Quaker economist Kenneth Boulding, who wrote about Spaceship Earth and spoke on the advances in science that could prolong life indefinitely. “But I ask you,” then forum board member and longtime environmental studies Professor Richard “Pete” Andrews ’70 (MRP, ’72 PhD) quoted Boulding as saying during his speech, “who would want to be an assistant professor for 150 years?”

“That was a period of a lot more broad societal consensus of concern about environmental issues, because of some of the events that had happened recently and a growing sense that the state-based solutions just weren’t working and weren’t sufficient,” Andrews, who died in May, told the Review. (See In Memoriam, page 76.)

The students who attended forum events that decade were galvanized by the first Earth Day, which had mobilized tens of millions of people two years after the Santa Barbara oil spill and Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River fire.

In 1975, white supremacist David Duke, who would later become the Grand Wizard of the KKK, came to campus to speak. Hundreds of Black students banded together to drown him out. “After his introduction, we clapped along with everyone else, but we kept on and on long after they had stopped,” D. Lester Diggs ’76, president of the Black Student Movement, told The DTH. “Finally, the program was canceled.”

The DTH received so many letters to the editor about Duke, a good portion of them advocating the position that Duke had as much right to speak as Civil Rights leader Ralph Abernathy, that the newspaper published the letters over the course of a week.

“As one who was a student during the period of the Speaker Ban Law in the 1960s and supported the efforts by the students of this institution to remove that threat to freedom of speech, I find this attempt by my fellow students to silence ideas of which they do not approve distressing,” wrote David Atwood ’67 (’72 PhD) in a Jan. 20, 1975, letter. “We cannot have a double standard on the issue of free speech.”

The forum continued to push boundaries. In 1977, it brought in psychologist Timothy Leary, known for his advocacy for psychedelic drugs. In 1979, it helped host Civil Rights activist Coretta Scott King and actress Cecily Tyson after her appearances in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman and Roots. In 1980, the forum brought in feminist and lesbian author Rita Mae Brown, Civil Rights leader and Atlanta Gov. Andrew Young, Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan and G. Gordon Liddy, who was the mastermind behind the Watergate burglary. In 1981, it sponsored an Equal Rights Amendment debate between Betty Friedan and Phyllis Schlafly. Four years later, it held a debate between social activist Abbie Hoffman and radical-counterculturalist-turned-businessman Jerry Rubin.

The end

The forum started to wane sometime in the early 1990s. “Whenever student groups are discontinued, lack of interest from new students is almost always a significant factor (barring scandal or other obvious reasons),” Nicholas Graham ’98 (MSLS), an archivist at the Wilson Special Collections Library, wrote in an email. “The UNC campus in the 1980s was a very different place than in the 1940s, and they may have had a hard time finding enough students interested in organizing the Forum talks.”

Hyder said he and others had to work during the summer, which may not have been something many students would want to do.

UNC’s Master of Public Policy program resurrected the Carolina Forum a few years ago. According to the forum’s website, the current version “creates a new space and a place for discussion and debate on big domestic and global policy challenges. The Forum fosters non-partisan discussion and deliberation. Its mission is to educate and to engage students in a dialogue about key policy issues in the U.S. and around the globe.”

Events were suspended during the COVID pandemic, but the forum plans to resume debates soon, said Tricia Sullivan, chair of the department of public policy. The forum is no longer student-led.

In its heyday, though, students were in charge and rubbed elbows with national and world leaders who brought their messages and ideas, frequently controversial ones, to UNC auditoriums packed with students eager to hear and agree or disagree with what they had to say. “It was truly exciting,” Hyder said.

Janine Latus is a freelance writer living in Chapel Hill. In previous issues of the Review, she has written about the renovation of James Taylor’s boyhood home, the preservation of photographs from the Jim Crow era and UNC’s response to the COVID pandemic.

Hyder joined the forum because he considered its presidency, along with the size of the forum’s budget and the influence it had on campus, the third most powerful position at Carolina. Only the president of the student body and the editor of The DTH wielded more influence among students, he said.

“A lot of people didn’t realize that the law made the point that anyone who had ever pled the Fifth Amendment was bad. Our point was that it affected more than just Communists. Anyone who was exercising their constitutional rights was banned.”

— George Nicholson III ’66, president of the Carolina Forum

“Whenever student groups are discontinued, lack of interest from new students is almost always a significant factor (barring scandal or other obvious reasons)…The UNC campus in the 1980s was a very different place than in the 1940s, and they may have had a hard time finding enough students interested in organizing the Forum talks.”

— Nicholas Graham ’98 (MSLS)

The Daily Tar Heel, June 25th, 1948

Carolina Forum ads from The Daily Tar Heel.

Truman Capote: February 19, 1976. Tom Wolfe: March 19, 1975.

On March 2, 1966, students listened to civil liberties activist Frank Wilkinson, who had refused to answer questions from a U.S. House committee about ties to the Communist Party. The Carolina Forum and other groups had invited Wilkinson (below, center foreground) to campus. He spoke standing a few feet off McCorkle Place because a state law barred anyone with communist ties from speaking on public property. The invitation led to the overturning of the law.

Carolina Forum ads from The Daily Tar Heel. G. Gordon Liddy: October 1, 1980. Who Killed JFK: October 11, 1975. Ford: Dec. 7, 1968.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.