STRIKE: Tense Days and Sober Leadership in 1970

Posted on April 29, 2020

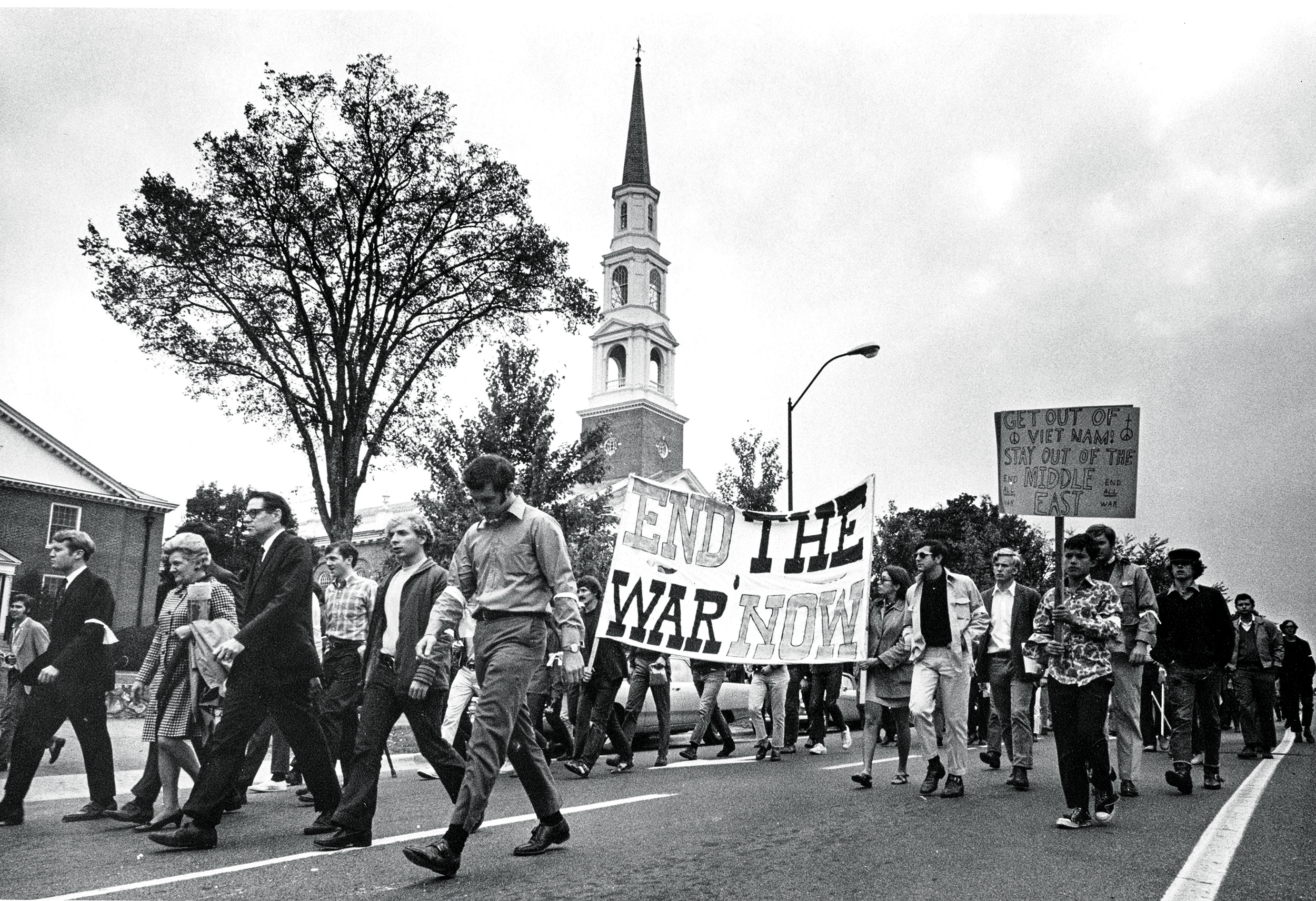

After some 6,000 people rallied in Polk Place on May 6, 1970, to hear anti-war speeches, about 4,000 marched behind coffins that symbolized the deaths of four students at Kent State. From there, it was on to Raleigh and Washington, D.C., for the UNC movement leaders. (“FOLDER 0870: ANTI-WAR ACTIVITIES: VIETNAM WAR, 1965–1970,” IN THE UNC IMAGE COLLECTION #P0004, N.C. COLLECTION, UNC)

We will not forget Kent State. We will not forget what Nixon is doing to America and to Asia.

And yet we cannot give the White House the satisfaction of a violent and destructive reaction to Nixon’s and the troopers’ demonstration of intolerance, impatience and aggression. We must not fall to their level of humanity. Violence is intolerable, whether it be in Cambodia, Vietnam, Kent State or on this campus.

— Tom Bello ’71

The student body president’s speech to some 6,000 people in Polk Place on May 6, 1970, had two distinct messages: Tom Bello was outraged personally at the U.S. military morass in Southeast Asia, in particular the recent foray into Cambodia and the deaths of four protesting students in Ohio that followed; and, amid daily headlines of violence on campuses across the country, Chapel Hill must keep its cool.

That many students and faculty opposed the war, he was confident. That their passions could be kept under control, nobody was certain. Two days earlier — before the news from Kent State — somebody had started a malicious fire in a temporary building that housed the Air Force ROTC.

On the eve of Bello’s speech at an all-students rally he called less than a month after he’d taken office, he said, “If the only way this nation is going to notice us is if we strike, then we will strike tomorrow and the next day and the next day.”

The Daily Tar Heel of Friday, May 1, had run a one-word headline — Cambodia — over a one-paragraph story that said President Richard Nixon had authorized several thousand ground troops to go in “to wipe out Communist headquarters for all military operations against South Vietnam.” The same issue of the paper reported that the Student Legislature had voted 28-13 to urge a class boycott by “all students whose consciences do not support United States military involvement in Southeast Asia” on the following Wednesday.

The dissenters protested; after the strike had begun, the Young Republicans Club called it “a meaningless blow at a helpless university” and condemned the anti-war movement.

The day after the vote, more than 1,500 had signed a petition condemning the Cambodia action. (The weekend headlines were occupied with the social highlight of the spring, a star-studded Jubilee so big it had to be moved to Kenan Stadium.)

On the morning of Tuesday, May 5, about 15 teaching assistants in the English department refused to convene their classes — the newspaper traced the start of the strike to that. Just after 1 p.m., some 2,000 students shouted “On strike, shut it down” as they marched from South Building, through Murphey Hall, past the AFROTC buildings, through the Union, through the Naval Armory and back through Polk Place.

The campus hadn’t seen anything like it, and seldom has since.

That evening, more than 3,000 marched to the homes of Chancellor Carlyle Sitterson ’31 (who also earned his master’s and doctorate from UNC) and UNC System President William Friday ’48 (LLB) — the message raucous enough that the Fridays moved to a hotel.

At the rally the next day, Bello said: “I am on strike and am urging strike, not to shut down this university but to express my commitment to whatever I can do to end the political careers of these insensitive, insecure and blatantly inadequate individuals who hope to gain at the expense of lives in Cambodia or Kent State. We must not be fooled by these cold, cruel men. If they will not come to us, we will go to them. Instead of burning ROTC buildings, we will beat these men at their own game of politics. …

“We will fast, we will pray, we will vigil. We will talk to the citizens of Chapel Hill and North Carolina. We will go to Washington and show Nixon what power is — not the power of guns and bayonets but the power of people and their votes.”

Sitterson read a telegram sent to the state’s U.S. senators and signed by Friday and all six of the state campus chancellors that reported UNC’s involvement in what by then was a state of apprehension at colleges everywhere: “We ask your support of immediate steps and actions to prevent any further acceleration of our involvement in Indochina and to hasten the end of our conflict.”

(Friday and the chancellors walked a familiar fine line during the strike. Gov. Bob Scott had sent a telegram, too — to Nixon, promising his support; this no doubt is what rang louder with many North Carolinians.)

The rally moved on to Franklin Street — some 4,000, led by Bello and four coffins. (There were about 16,000 students at Carolina at the time.)

On Thursday, a meeting of the faculty in Hill Hall that was piped into McCorkle Place for the students produced an amnesty policy that offered the grades currently carried for those who would miss late-semester classes and exams. It was symbolic — University policy already allowed faculty to grade on completed coursework or finish assignments later in special situations.

The strikers meanwhile turned their attention to marches in Raleigh and Washington.

On May 5, bomb threats led to evacuations of three buildings on campus. On May 8, a homemade bomb blew out windows of the Student Stores. There were no injuries, and for the most part, violence was averted.

Anne Queen, who directed the Campus Y from 1964 to 1975 — a tempestuous decade at the campus epicenter for student-initiated social justice — wrote to Bello that his election had been a fortunate day for the University; she said she’d never (including the Speaker Ban days) heard a better student speech. Bello ended it with:

“And even more than this, we go on strike to open up a new university; to create a free university. This meeting is not the culmination of our efforts; rather, let it be the beginning of an educational system built not on class attendance or grades, but as evidence by this meeting today, one built on the principles of free exchange of ideas, open expression of opinion, and learning through personal interaction and involvement. We strike to establish a university that will espouse what this society so desperately needs: mutual love, respect and understanding.”

Tom Bello, who had a career as a schoolteacher, died in 2016.

— David E. Brown ’75

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.