TEACCH Your Children Well

Posted on Jan. 8, 2024A program created at Carolina decades ago revolutionized care and services for kids with autism worldwide.

by Mark Derewicz

Linda Varblow ’91 (MPH) said what Carolina’s TEACCH offers is not super complicated, “but it’s life-changing for families.” (Photo: Carolina alumni/Cory Dinkel)

Jesse Holloway, not yet 2 years old, fixated on a ceiling fan, fascinated. His mother, Linda Varblow ’91 (MPH), handed him his favorite Matchbox car, and Jesse rubbed the wheels with his fingertips, obsessed with the texture, as if the feel of the spinning wheels was far more interesting than racing the car down a track. He also carried a tennis ball wherever he went, constantly turning it over and over and over.

“When Jesse stopped responding to his name and started flapping his hands, I knew something was off,” Varblow said. “This was a boy who said his first word at 1 year old and would bring books for us to read together. We thought he was a genius.”

But then around the time Jesse reached age 2, it was like the boy Varblow knew wasn’t there anymore.

At a psychologist’s office, Jesse repeatedly flipped window blinds with his fingers. The doctor thought Jesse was merely adjusting to life in the United States after the first 18 months of his life spent in London, where his father, Jim Holloway, had taken a job with GlaxoSmithKline. The doctor diagnosed Jesse with selective mutism, a condition in which a person cannot speak in certain situations. Varblow, a trained nurse, was suspect. So, she convinced her pediatrician to set up an appointment for Jesse at the Carolina Center for Development and Learning, which is now the Carolina Institute for Developmental Disabilities. There, psychologists diagnosed Jesse with autism. That was May 1994; Jesse was 25 months old.

That’s an early diagnosis for autism, especially given where autism research was 30 years ago. The diagnosis was about as important as what came next. UNC psychologists told Varblow about UNC TEACCH Autism Program, a Carolina-based enterprise so unique that families from around the world have uprooted their lives to live near it.

“It’s fair to say dozens of families with autistic children moved to the Chapel Hill area,” said Lee Marcus, director of the original TEACCH clinic in Chapel Hill from 1974 to 2008 and director of clinical training until 2016. Back in the 1970s, ’80s and even ’90s, many communities didn’t provide services for children with autism. “So, if families could, they’d come to us,” he said.

As fate would have it, Varblow and her husband had moved back to Chapel Hill from London right before Jesse, who would later graduate from Carolina in 2014, was diagnosed. “We did not move here for TEACCH,” she said. “But we would have. Had we still been in London when Jesse was diagnosed and learned about TEACCH, we would’ve moved here in a second.”

Varblow knows this not only because the experiences with TEACCH that Jesse — and later his younger brother, Jonah, or “Joey” — had, but because she’s been working at the center since 2001, many of those years as a clinical instructor and autism specialist.

“I can’t attribute the positive change in Jesse — and later Joey — to anything else,” Varblow said. “TEACCH was the main thing we did.” What TEACCH offers is not super complicated, she said, “but it’s life-changing for families.”

Why Carolina?

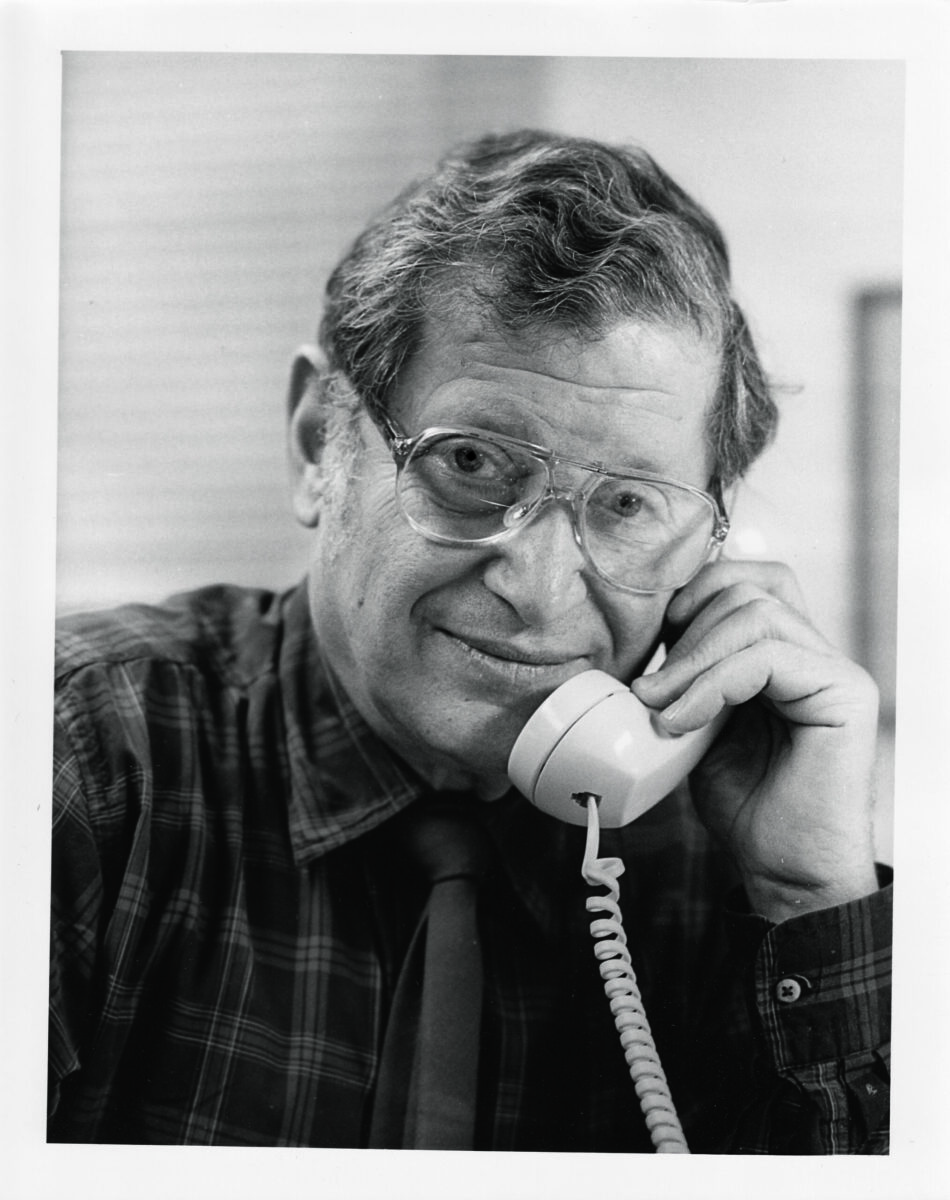

Lee Marcus, who was with TEACCH from 1974 to 2016, led the push to establish TEACCH workshops in every county in North Carolina to train educators, psychologists and parents. (Photo: Carolina Alumni/Cory Dinkel)

Autism is called a spectrum disorder because, as the saying goes, if you meet one person with autism, then that means you’ve met one person with autism. The condition is so complicated and dependent on an individual’s genetics, neurobiology, psychology and experiences that each person’s autism will be and appear different. Some kids with autism will never learn to speak and will need to live with caregivers their entire lives. Some will become savants in their chosen field and live independently. And many will fall between these two extremes. (See “What is Autism?” page 43.)

When Marcus was a graduate student and postdoctoral fellow in Rochester, New York, in the early 1970s, a few psychologists taught him they thought autism might not be as simple as an emotional disturbance. So, Marcus went to a state institution to observe kids. “It was a warehouse,” he said. “There was basically no staff there trained to help anyone.” The kids merely existed, largely misunderstood and recipients of little care.

Marcus, too, was not trained to care for kids, but he was so interested in helping these children that in 1974 he interviewed for a job at a new program in Chapel Hill led by psychiatrist Bob Reichler and psychologist Eric Schopler, whose research in the 1960s revealed that most autistic children were not emotionally disturbed. Rather, they seemed to have a neurodevelopmental condition, a theory that contradicted the belief at the time that emotionally distant parents caused the disorder. When Schopler was working on his PhD in the 1960s at the University of Chicago, one of his psychology professors compared the parents of autistic children to the Nazis, whom Schopler’s family had fled in 1938. (See “Helped Families of Autistic Children Everywhere,” September/October 2006 Review.) “The field was pretty bleak,” Marcus said. “They didn’t know too much about autism, and what they thought they knew was wrong.”

Through several years of clinical research, Schopler documented how kids behaved, how they learned, how they saw the world and dealt with reality as they experienced it. He developed a method called structured teaching, which involves a few principles based on what he observed in all children with autism: They are primarily visual learners, as opposed to learning through hearing information.

Eric Schopler, who died in 2006, was a pioneer in autism research. His work led the state of North Carolina to fund the UNC TEACCH Autism Program in 1972, four years before Congress mandated public schools provide educational services to children with autism and other conditions. (Photo: Furman University/University of Akron)

To help a child with autism, Schopler realized the physical environment must be organized in a way that makes the most sense to the child, not to teachers or parents. In a classroom, for instance, teachers would set up areas to conduct specific tasks. The areas would be marked visually and would not change locations. For children with autism to succeed in a classroom, they must experience a predictable sequence of schedules, routines, activities and work. Schedules should be written down. Activities should have visual cues the children can easily see. But because the world is not predictable, Schopler included flexibility in his method. For instance, if the predictable schedule says it’s time for a walk, the caregiver or teacher may offer different routes for the walk during the week. Teachers should precisely plan when they introduce flexibility into children’s routines and activities.

Schopler and Reichler saw children thrive in structured environments that had visual cues, predictability and managed flexibility. They documented how they trained parents to help their children succeed in school and everyday life.

Schopler’s research led the state of North Carolina to fund the UNC TEACCH Autism Program in 1972, when Schopler and Reichler introduced structured teaching in 10 state public schools and in special state-funded clinics, including in Chapel Hill. The program was created four years before Congress mandated public schools provide educational services to children with autism and other conditions. TEACCH was ahead of the curve. In fact, it inspired the curve. Parents of children with autism heard about Carolina’s program at autism conferences and by reading journal articles. Some families with the means to do so moved to Chapel Hill to work directly with TEACCH instructors for years as their kids traversed adolescence.

After Schopler and Reichler hired Marcus as TEACCH director in 1974, Marcus led the push to establish TEACCH workshops in every county in North Carolina to train educators, psychologists and parents.

There are now seven outpatient TEACCH clinics in North Carolina. TEACCH instructors have conducted thousands of workshops in all 50 states and in many countries during the past 50 years. In 2022, TEACCH trained 5,600 educators and psychologists from 46 countries and 42 states in the U.S.

A story of successes

Back in the mid-1990s, Varblow was so impressed with Jesse’s progress at TEACCH she created a replica of the TEACCH therapy room in her house, which became covered in Velcro so she could attach visual cues to help her sons with daily routines, schedules and activities. “Sometimes when things got quiet, and we weren’t sure where Jesse was, we’d find him doing activities in the therapy room because they made so much sense to him,” she said.

Joey Holloway ’18 was diagnosed with autism when he was a toddler, as was his older brother, Jesse Holloway ’14. Joey, 29, graduated from Carolina with a degree in biology and a minor in computer science. He works part time at a genetics lab and part time at Carolina’s TEACCH autism program. Jesse majored in physics and philosophy at Carolina and earned a master’s in the philosophy of physics at the University of Michigan. (Photo: Carolina Alumni/Cory Dinkel)

When her son Joey was born, she assumed odds were he would not have autism. But research would eventually reveal that younger siblings of kids with autism are at a higher risk of developing the condition.

Varblow felt indebted to and enthralled with TEACCH, and in 2001 the center offered her a job as an office manager. Four years later, Marcus hired her as an autism specialist.

Part of the TEACCH philosophy, Varblow said, is that TEACCH clinicians are generalists who do a bit of everything but might specialize in one field. Some TEACCH clinical instructors/autism specialists have a master’s degree in public health, like Varblow does. Some are social workers, psychologists, speech pathologists or occupational therapists. But all of them are autism specialists, and all of them work as therapists at seven outpatient clinics across the state and within various communities, training counselors at Morehead Planetarium one day and EMT students at Durham Tech the next. Varblow has conducted trainings internationally and nationwide, and she has given presentations at schools, including her sons’ schools, to educate teachers and students about autism.

By far the most popular training event TEACCH offers is a five-day, intensive workshop where parents and educators engage in structured teaching in mock classrooms with children who have autism, rotating in and out so that participants can learn how children respond differently to different aspects of structured teaching.

Varblow’s sons participated in the workshops for years, helping their mother and other instructors train parents and educators from around the world, showing everyone their love of learning within the TEACCH method.

Varblow now focuses on older teens and young adults with autism, who might benefit from strategies to help them succeed in college and the workplace. The T-STEP program — TEACCH School Transition to Employment and Postsecondary Education — helps kids navigate this tricky stage of life.

Carolina psychologist Laura Klinger was a TEACCH intern under Marcus and returned to Carolina as TEACCH executive director in 2011. She is now a renowned autism researcher and clinician. “Our research shows students enrolled in the T-STEP program are more prepared for work,” she said, “and they report less anxiety and more opportunities in making decisions for themselves.”

Jesse, now 31, progressed very well during childhood thanks largely to structured teaching, which helped him excel in Chapel Hill-Carrboro public schools. “Going through the school system, I was very fortunate to learn from many excellent teachers,” he said. “I remember how hard they worked to help me and others.”

Jesse majored in physics and philosophy at Carolina, graduating in 2014, and earned a master’s in the philosophy of physics at the University of Michigan. He now works for UPS and lives with his partner in Toledo, Ohio. Joey, 29, graduated from Carolina in 2018 with a degree in biology and a minor in computer science. He works part time at a genetics lab at Carolina and part time at TEACCH, where he processes continuing education credits for TEACCH workshop participants among other responsibilities.

As a parent and TEACCH instructor, Varblow knows the ins and outs of autism like few others. No matter where on the spectrum a person falls, life presents different challenges for them. “High-functioning kids with autism often have depression and anxiety, and it’s just unfortunate. I see it all the time,” Varblow said.

Jesse struggled during the COVID pandemic and decided not to finish his doctoral work or pursue a career in academia. “I’m not glad Jesse didn’t finish his PhD work; he was so close,” Varblow said. “But I’m glad he left when he did. I didn’t even recognize him when I visited. But now I feel like I have him back.

“For seven years, Jesse thought he was going to be an academic, and that one thing is not part of his life anymore,” she said. “In time, he will decide what’s next.”

My child is back

Varblow and her son Joey Holloway ’18. Both Joey and his brother Jesse were diagnosed with autism when they were toddlers. (Photo: Carolina alumni/Cory Dinkel)

About one in 36 children born in the U.S. will be diagnosed with autism, according to 2020 data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As a result, TEACCH continues to expand due to the growing need for trained educators, clinicians and caregivers. When the pandemic hit and TEACCH decided to provide virtual workshops, TEACCH instructors realized what they could and couldn’t achieve on Zoom. They still provide virtual workshops, but in-person training with kids with autism is still most effective, Varblow said.

Current programs include TEACCH for Toddlers, School-age Social Skills/Emotion Regulation, Transition to Adulthood, and Adult Mental Health. TEACCH offers an employment program for autistic individuals in the Triangle and Triad regions of North Carolina, and it created a residential program in Pittsboro, where youth with autism live and learn together. TEACCH instructors train caregivers and educators in mental health care and suicide prevention, and TEACCH is leading efforts to understand how children with autism in underrepresented groups are affected differently.

As TEACCH expanded over the years, state funding did not keep up, Varblow said. TEACCH now uses a fee-for-service model to provide a wide range of services and trainings worldwide. But its mission remains the same.

“We still strive to help families understand autism and how their child learns,” Varblow said. “A lot of parents don’t think about their child’s thinking and learning styles until we explain why kids do some of the things they do. Then, light bulbs go off.” And when the parents understand their children, the children feel seen. Together, they go on a journey.

The TEACCH approach to structured teaching is now established in the field, highlighted in leading journals, magazines and websites dedicated to autism, and it is taught in workshops unaffiliated with UNC TEACCH.

And to think it all started when a couple of researchers decided they didn’t know everything. Schopler and Reichler observed how kids behaved, and they talked to parents, who let TEACCH instructors learn what the kids were trying to show them and what they needed to be themselves and thrive.

As the children benefited, TEACCH thrived, too. Now, thanks to TEACCH, tens of thousands of children, parents, educators and caregivers have access to the latest and greatest evidence-based autism services available.

“I know I’m a poster child for TEACCH, and I can tell you this after all these years, I am passionate about it,” Varblow said. “But I see no less passion in everyone else who works here.

“Before I found TEACCH, I felt like I lost my son for a while. I was frantic and didn’t know what to do,” she said. “TEACCH gave me my child back.”

Mark Derewicz, a freelance writer living in Chatham County, is director of research and national news for UNC Health Communications and News Team.

What Is Autism?

As a spectrum disorder, autism is not one thing. Carolina researchers have documented that the brains of children with autism are wired differently. The changes appear even before autism symptoms reveal themselves.

Babies and toddlers developing autism will often avoid eye contact, stop responding to their name and begin interacting less with parents. They might not show facial expressions of sadness or joy. They won’t care to share what interests them, such as a toy or something they noticed and would, without autism, typically point to. They might not notice when others are upset or hurt.

People with autism generally struggle in social situations and with communicating — both receiving information and expressing themselves. They easily lose focus, making learning difficult. They often act impulsively and can be hyperactive and moody, and their reactions can seem overly emotional to others. Kids with autism often repeat behaviors, such as speaking the same word in conversation or banging toys together. They often restrict their own behaviors, such as repeatedly watching the same movie or playing with the same toy in the same way every time. Some kids develop epilepsy and seizures. Some struggle with anxiety and depression.

According to research studies, older people with autism have higher risk of gastrointestinal disorders, hypertension, diabetes, obesity and sleep disorders.

— Mark Derewicz

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.