The Bank of Itta Bena

Posted on July 29, 2021

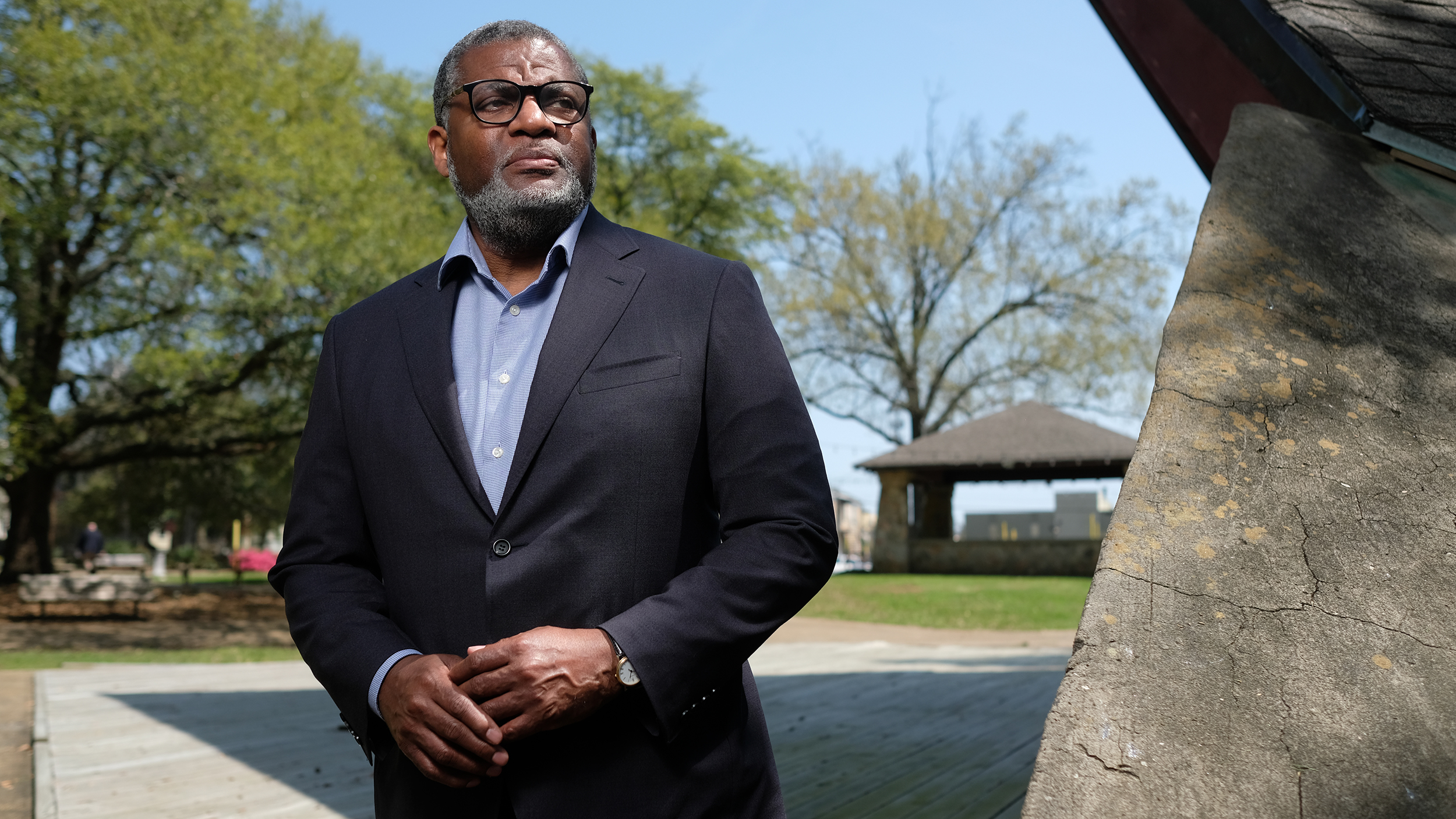

(AP Images/Charles A. Smith for the Carolina Alumni Review)

Bill Bynum ’80 learned that legal equality was missing something without material equality. He is a giant in the business of pooling resources in rural, impoverished places.

by Eric Johnson ’08

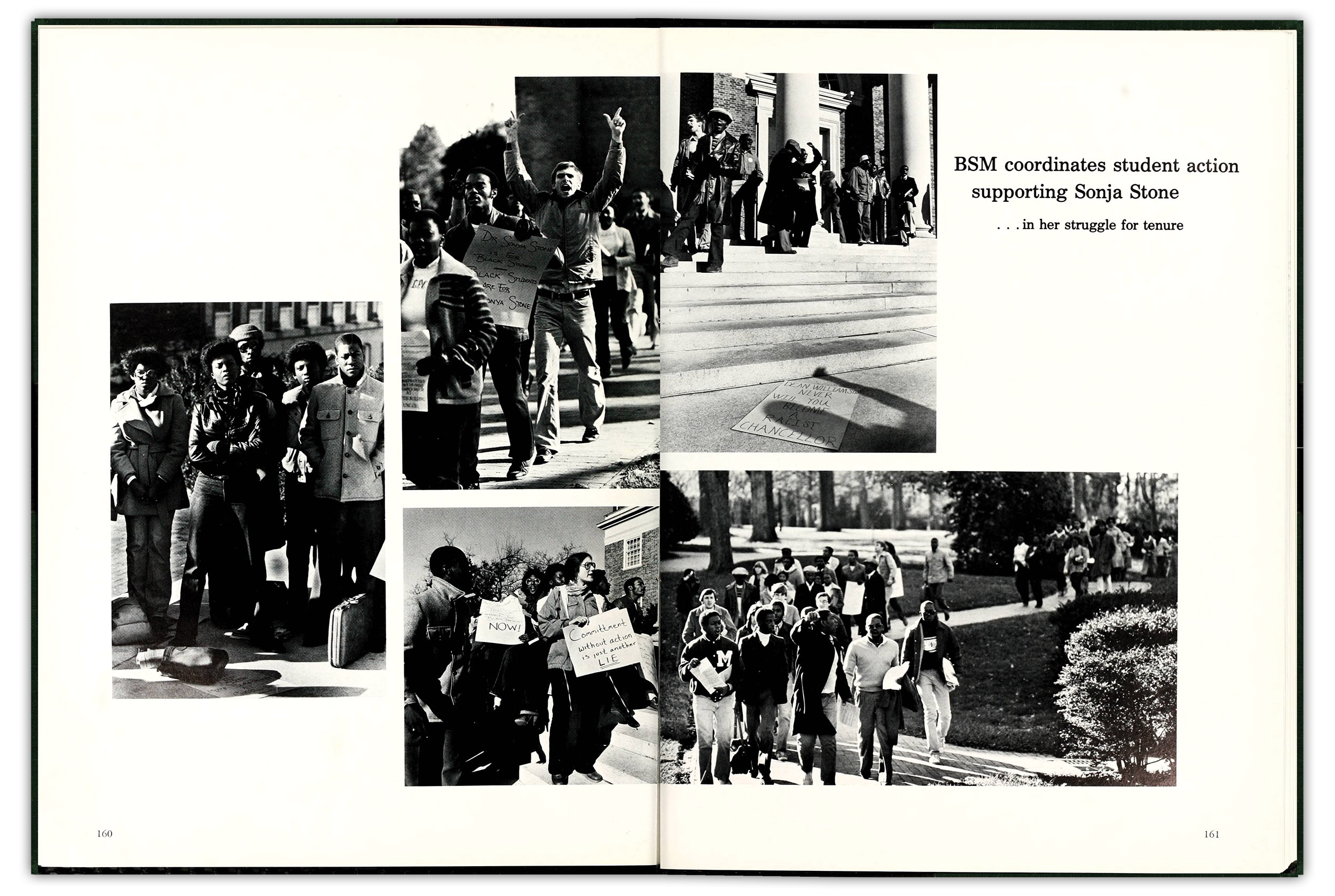

It was the late 1970s, and UNC was roiled by debates over Black enrollment, pressure to recruit more diverse faculty and the University’s decision to deny tenure to the head of the African and Afro-American studies curriculum, Sonja Haynes Stone. Bill Bynum ’80 was chair of the Black Student Movement. Bynum, a student of Stone, led the BSM in a series of marches and protests against the tenure decision. Campus leaders refused to budge.

“Chancellor [Ferebee] Taylor [’42] told us we didn’t have any recourse,” Bynum recalled. “Which is probably the worst thing you can say to students — that there’s nothing you can do. So, we kept the pressure on, we kept protesting.” A two-page spread in the 1980 Yackety Yack shows a long line of students chanting their way across campus and thronging the steps of South Building. After the provost refused to meet with them, they launched a sit-in.

“Up until that point, I had probably been floundering around in Chapel Hill, trying to figure out where I could get traction,” Bynum said. He’d come to campus having spent most of his childhood in rural Chatham County, where he was bookish but athletic. He had vague notions of playing football, becoming a sports writer or both.

He earned a spot on the football team, but “as a walk-on, you didn’t get the academic support or the same level of training,” he said. “By the time practice was over, I was spent. And my grades were suffering. I needed to find some focus.”

After Stone won her tenure fight on appeal, civil rights attorney Julius Chambers ’62 (LLBJD), who was involved in a federal lawsuit about the slow pace of UNC’s integration efforts, asked Bynum to testify in Washington, D.C., about the environment on campus. Bynum’s future began to take shape.

“All of that gave me a sense of the possibilities of being a lawyer or doing advocacy of some sort,” Bynum recalled. “I thought I was going to go to law school, become the next Thurgood Marshall or something.”

Although he was waitlisted at Carolina law, the battles over Black representation on campus had galvanized Bynum in a way that would never abate. Bynum would find a different way to fight for Black equality in America — not in courtrooms but in banks. Not through legal judgments, but through material equality and the power over one’s life that comes with it. Along the way, Bynum would become one of the country’s most respected and effective voices for that cause.

In the late 1970s, Bynum was chair of the Black Student Movement. He led the BSM in a series of marches and protests against the University’s decision not to offer tenure to his professor, Sonja Haynes Stone.

Money matters

In the last speech of his life, Martin Luther King Jr. offered his followers some financial advice. He was in Memphis, Tenn., to support striking sanitation workers, most of them Black, demanding better wages and better treatment. It was part of the Poor People’s Campaign that King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference launched in 1967.

“We’ve got to strengthen Black institutions,” King said to rising applause inside the cavernous Mason Temple. “I call upon you to take your money out of the banks downtown and deposit your money in Tri-State Bank. We want a ‘bank-in’ movement in Memphis. Go by the savings and loan association … put your money there. You have six or seven Black insurance companies here in the city of Memphis. Take out your insurance there. We want to have an ‘insurance-in.’ Now these are some practical things that we can do. We begin the process of building a greater economic base, and at the same time, we are putting pressure where it really hurts.”

King and other civil rights leaders long maintained that legal equality was only one part of the equation. Material equality — the ability of Black Americans to make a decent living and build wealth — would matter just as much in a society where money and power are near synonyms.

Today, Bynum is a leader for King’s message. Instead of following in Thurgood Marshall’s footsteps, he became a banker, founding Hope Credit Union and the Hope Enterprise Corp. to bring jobs and wealth to the Deep South. “If you work in philanthropy in the South, you’re going to know of Bill Bynum,” said Sherry Magill, former president of the charitable foundation the Jessie Ball DuPont Fund and a longtime champion of economic development in the Southeast. “If you’re interested in how to move capital to places where capital doesn’t want to go on its own, you’re going to bump into Bill Bynum.”

Bill Bynum ’80 is trying to address the American racial wealth gap in one of the poorest regions of the country, proving that a community-first model of capitalism can help reverse a cycle of poverty that goes back generations.

From its base in Jackson, Miss., Hope serves more than 35,000 people in high-poverty communities across the Mississippi Delta. Overwhelmingly, these are people and places shunned by traditional banks.

“We simply applied the bank model to places the banks had abandoned,” Bynum said at a Southern Futures forum at Carolina in 2019. “We go to places that are bank deserts, essentially. It’s not rocket science. We didn’t need to reinvent the wheel; we just had to bring the wheel to people who didn’t have the wheel.”

The racial wealth gap in America is staggering. The typical Black family has one-eighth the wealth of the typical white family. Black families are far less likely to own a home, and home values in Black communities are significantly less than those in comparable white neighborhoods. And Black Americans are far less likely to have a traditional bank account. That leaves Black households more reliant on payday lenders, check-cashing centers and other high-cost alternatives that are more likely to rack up debt than build wealth.

Bynum is trying to address all of that in one of the poorest regions of the country, proving that a community-first model of capitalism can help reverse a cycle of poverty that goes back generations. In its annual impact report, Hope highlights the percentage of mortgage holders who are first-time homebuyers and the fact that the average credit score of a Hope borrower is well below the national norm. Hope serves those customers with small-dollar emergency loans, low-fee checking accounts and higher-than-average deposit rates even for small balances.

“The financial tools are a means to an end,” Bynum said. “The end is helping people build agency, to take control of their lives.”

It’s a model Bynum first honed in North Carolina. After graduation, still stuck on the law school waitlist — he never went — Bynum interviewed for a community organizing job with an upstart advocacy organization called the Center for Community Self-Help. Based in Durham and founded by a social justice activist named Martin Eakes, Self-Help was a nonprofit trying to organize the employees of struggling rural factories to form worker cooperatives.

“We were so young and poor,” Eakes recalled. “I remember telling Bill, ‘We’ve got enough money to pay you for the first three to six months, then you’ve got to figure out how to earn your salary.’ He took the job anyway.”

For Bynum, it was a window into the role that economics could play in cementing civil rights. Progress in the courtroom didn’t always translate into real improvement in quality of life. “It was the early 1980s, and I was watching some of the legal decisions I thought were settled doctrine really getting pushed back,” he said. “I really started to feel that economic opportunity was more durable than legal decisions.”

He helped Eakes build Self-Help into a highly successful credit union, offering loans and bank services to single mothers, Black business owners, recent immigrants and other groups that traditional banks ignored. Bynum helped build partnerships with the N.C. Rural Center and deepen the credit union’s focus on economic development in poor communities. “I saw the potential of people pooling their resources together to help each other,” he said. “I got very interested in that career, and that’s what I’ve been doing ever since.”

In many of the areas where Hope operates — such as Itta Bena, Miss. — all the money that local residents could hold in a bank is minuscule, “certainly not enough,” Bynum says, “to create the opportunity ladders that people in that community need.” (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

Putting money to work

Hope, like Self-Help, started small. After Bynum was recruited to run the Enterprise Corporation of the Delta in Jackson, he met a pastor who was trying to form a community credit union so his congregants wouldn’t need to rely on check-cashing stores and pawn shops. Bynum stepped in to help, and Hope was born. “I was introduced to credit unions as a kid,” Bynum said. “It has always seemed to me like a very logical way for people to address their financial needs and benefit the whole community.”

Convincing people to hold their money in a bank is important for all kinds of practical reasons, but none more crucial than this: It creates more money. A hundred dollars socked away under somebody’s mattress just sits there, but $100 in Bynum’s bank goes back out the door as loans. And not just once but multiple times. A hundred dollars in the bank can support several hundred dollars in lending, and all of that money is available to the people and businesses that need it. That’s how banks increase the amount of wealth circulating in the community — how they “deploy capital,” to use the language of economists.

“It’s a little like the fishes and loaves in the Bible,” said Magill, the former Jessie Ball DuPont Fund president. “You’re multiplying money, basically, to feed these capital-starved areas of the country. When you put that money to work, it creates jobs for somebody else, it creates income for somebody else.”

“We have more than 70 percent of the deposits in Itta Bena, but that equals $1.2 million. That’s certainly not enough to create the opportunity ladders that people in that community need. And there are Itta Benas across the Delta, across the Deep South, in Appalachia, in Latino communities.”

—Bill Bynum ’80

But to multiply capital, you have to have money to work with. In many of the areas where Hope operates, the entire deposit base — all the money that local residents could hold in the bank — is minuscule. In the tiny Delta town of Itta Bena, Miss., Hope is the only bank left standing, and that still leaves a paltry amount of capital to reinvest. “We have more than 70 percent of the deposits in Itta Bena, but that equals $1.2 million,” Bynum said at the Aspen Institute’s 2021 forum. “That’s certainly not enough to create the opportunity ladders that people in that community need. And there are Itta Benas across the Delta, across the Deep South, in Appalachia, in Latino communities.”

Fixing that problem means attracting money from outside the community, and Bynum is at the leading edge of a movement to persuade big companies to hold a chunk of their savings in small, minority-serving institutions like Hope. Netflix made national headlines last summer when the company moved $10 million into an account with Hope, something Bynum’s team calls a “transformational deposit.” Netflix isn’t giving the money away; it’s just holding a small fraction of its cash reserve at Hope instead of socking it away in a major national bank. It makes minimal difference to Netflix, but it’s a huge difference in the amount of capital Hope can deploy in areas that need it.

“That $10 million has an incredible impact in bringing resources to these communities where capital has been extracted,” Bynum said at Aspen, where he appeared alongside Netflix CEO Reed Hastings. “Bill is a stubborn guy,” Hastings said. “He’s been doing this work at Hope for more than 20 years, so he’s just incredibly dedicated and focused on doing loans and investments in businesses that work.”

Bynum and Hastings go way back. They were in the Aspen Institute’s class of Henry Crown fellows together in 1998, when Netflix was a fledgling DVD rental company trying to compete against Blockbuster. Now, as one of the biggest media companies in the world, it’s able to pump millions into the Mississippi Delta and pressure other corporations to do the same.

“We took 2 percent of our corporate assets … we normally keep that money at JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley, big safe institutions, but not as invested as Bill is at taking those deposits and then investing them into the community,” Hastings said. “If all American companies could just take 2 percent of their balance sheets, their cash reserves … to be in Black-owned banks and economic development organizations, then we’d have a profound shift in the capital base that’s very powerful.”

A key part of Bynum’s mission is getting powerful people to pay attention to places like Itta Bena — where Hope is the only bank left — to notice whole regions facing economic decline. (Ed Sivak/Hope Credit Union/Google Maps)

A key part of Bynum’s mission is getting powerful people to pay attention to places like the Delta, to notice that headlines about national economic growth can gloss over whole regions facing economic decline. “You have to be a salesperson, in that you have to draw resources from outside the community into the community,” said Eakes, at Self-Help. “And Bill is one of the most respected spokespeople for community lending in the United States. He can speak with Treasury secretaries, with the chair of the Federal Reserve, with governors. He has the ability to influence people. And as a Black man serving low-income communities in the Delta region, he has a certain elevated level of credibility.”

That national pull was on full display in February 2019, when Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell trekked to Mississippi Valley State University for a Hope-sponsored conference on rural places missing out on an otherwise booming economy. In the careful, academic language of the Fed, Powell lamented the trend of bank closures in small towns across the country.

“Industry consolidation has led to a long-term decline in the number of community banks,” he said. Data from the Fed shows that rural counties in the South saw especially steep declines in bank access in the years following the Great Recession.

“The loss of the branch often meant more than the loss of access to financial services; it also meant the loss of financial advice, local civic leadership and an institution that brought needed customers to nearby businesses.”

The speech was dry, as Fed speeches tend to be. But the image of Jay Powell standing at the blackboard in a small, historically Black college in Mississippi, talking with students and shaking hands with local officials — that signaled a real shift in the way national policymakers think about economic geography. It also generated a lot of national news stories about Hope’s work and the struggle of rural communities in the South.

The Fed is paying attention. Starting in February 2019, the central bank embarked on a listening tour designed to bring the voices of regular people into the world of monetary policy. That effort included focus groups in the rural South about the impact of closed banks and fewer financial resources.

“We actually see an important part of our role as helping to shine a light on those historical and systemic barriers and how they play out,” said Daniel Paul Davis, vice president and community affairs officer at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “We’re trying to take that more seriously, honestly. There’s clearly something that keeps communities that have experienced generational poverty for generation after generation, there’s clearly something systemic there that needs to be addressed.”

Advocates like Bynum have been instrumental in getting Fed economists to look beyond raw data, to hear stories about how real people navigate the financial system — or get sunk by it. “We’ve entered an interesting point where the connections between what’s happening at the household or neighborhood level … we’re starting to understand that those micro-level interactions have a real impact on the macro economy,” said Davis. “We’re trying to truly connect those dots.”

After George Floyd, a surge

Bynum is making sure those neighborhood-level insights are heard at the highest levels. He worked with President Joe Biden’s transition team, offering advice on revamping financial regulations. “We have a lot of data and a lot of stories from this part of the country that should be considered in policymaking,” Bynum said. “I think they took them seriously.”

Demonstrating how Washington policies can aid or ruin the lives of poor people in small Southern communities has been key to the Hope mission from the beginning. Bynum served as chair of the advisory board for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Treasury Department’s consumer development advisory board. Hope has its own policy institute that publishes research on everything from college scholarships to bail reform, focusing on the issues that affect wealth and economic opportunity for low-income people.

Bynum is at the leading edge of a movement to persuade big companies to hold a chunk of their savings in small, minority-serving institutions like Hope Credit Union. Netflix made national headlines by moving $10 million into an account with Hope, something Bynum’s team calls a “transformational deposit.” It makes a minimal difference to Netflix, but it’s a huge difference in the amount of capital Hope can deploy in areas that need it.

“Our role is to make sure the lessons from the people and communities we serve are front and center in the conversations that policymakers and banks are having,” Bynum said. “They’re so often not at the table and don’t have the knowledge that the table even exists. We’re in a position to take their voices, take data from their experiences, and share them.”

Decisions made deep in the federal bureaucracy — the rules for credit reporting bureaus, enforcement of the Community Reinvestment Act, bank oversight from the comptroller of the currency — can have a huge impact on whether low-income people are able to buy cars, start businesses or afford college. Bynum and his team also keep watch on predatory financial practices like payday loans, high overdraft charges and balloon mortgages that can cause people to lose their homes.

“We’re working in communities where wealth has been extracted for centuries and has never been allowed to grow,” Bynum said. He’s become more comfortable speaking bluntly with groups like the Business Roundtable, where some of the wealthiest corporate leaders in the country invited him last year for a discussion about race and wealth. “I guess when you’ve been at it for a while, you feel more comfortable saying what needs to be said. I do feel like I represent a lot of people who are counting on me to take that message to halls of influence and power, and I don’t want to sell them short.”

Those conversations intensified last year. The coronavirus pandemic and the accompanying public health restrictions have devastated Black businesses, and the protests over the death of George Floyd brought renewed attention to wealth gaps and persistent poverty. A fledgling movement to “Bank Black,” or shift more deposits and investments to Black-owned banks, gained momentum, and books like The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap surged in popularity.

“We simply applied the bank model to places the banks had abandoned,” Bill Bynum ’80 said at a forum at Carolina in 2019. “We go to places

that are bank deserts, essentially. We didn’t need to reinvent the wheel; we just had to bring the wheel to people who didn’t have the wheel.” (AP Images/Charles A. Smith for the Carolina Alumni Review)

“I have seen more recognition in terms of equity and inclusion in recent months than I’ve heard in 40 years of doing this,” Bynum said late last year. “George Floyd’s murder had an effect that nothing else has had. When you see a majority of Americans acknowledging the legitimacy of Black Lives Matter, acknowledging systemic racism and institutional barriers that limit some people more than others — I think that opens opportunities that I’ve not seen before.”

From his home in Jackson, Bynum has been trying to translate those opportunities into action. At the same time, Hope has been scrambling to address the financial devastation the pandemic has wrought in poor communities. Black-owned businesses were almost twice as likely to close as white-owned firms last year, in part because they operated on thinner margins even before the pandemic. Black businesses also had a harder time accessing government relief programs.

When the first round of federal stimulus money was released across the country last year, activists were dismayed by how few Black-owned businesses secured emergency assistance from the Paycheck Protection Program. The loans were handled through banks, so companies without a well-established banking connection struggled to get funding.

“Most Black-owned firms lack strong bank relationships,” reported a study of PPP loans from the New York Fed. “Black business owners are also more likely than white owners to report being discouraged, or not applying for financing because they believe they will be turned down.”

Hope was an exception. The credit union approved more than 3,000 PPP loans last year — most of them to minority-owned firms — compared to a few hundred small-business loans in a normal year. “It’s really been heartbreaking to see how many small businesses have struggled over the past year,” Bynum said. “Our borrowers have typically been very small businesses — mom and pop places, barbershops, restaurants. We really want to extend a lifeline to help them stabilize and put them on a path to getting stronger afterward.”

Hope could do that because of well-established relationships in the small communities where it operates, something that’s been lost in much of the country as banks retreat from low-income areas.

Bynum knows he’s pushing against a powerful tide. The economic shocks of the past 15 years, from the Great Recession to the millions of jobs lost during the pandemic, have fallen harder on the very people he’s trying to serve. The racial wealth gap has actually increased in the past 30 years, and the Mississippi Delta still has some of the deepest poverty in the nation.

But he’s not tired, and he’s not done. “Hope is that essential human quality that enables people to live beyond their present situation,” said Mississippi’s late Gov. William Winter, speaking in a video tribute to Bynum in 2013. “Hope recognizes that we are all bound to each other, that we are a part of a common humanity.”

Hope also is the name of Bynum’s late wife, who died in 2019 after a lifetime of working for colleges and social service organizations. “She was an inspiration for much of the work we do,” Bynum said. “I told her when we moved to Mississippi that we’d give it three to five years. It’s been 26 years now, so things have worked out. I’m a masochistic optimist — I don’t think you could do this kind of work if you didn’t think there was a better future, and you could contribute to it.”

Eric Johnson ’08 is a writer in Chapel Hill. He works for the College Board.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.