The First 100 Years

Posted on May 8, 2023A writer who honed his craft while running the cash register at a Franklin-Street fixture looks back as it celebrates its centennial.

by T. Edward Nickens ’83

I wish I could remember her full name. Mary. Mary Something. She was an older lady, gray-haired and slightly mischievous. I believe she was a poet. I do recall she was an artist who used dried flowers in her work. She was also a Sutton’s Drug Store regular and always sat on the short end of the old-fashioned pharmacy’s L-shaped soda fountain counter.

In the late afternoons I would move from my regular post behind a nearly prehistoric cash register at the front of the store and work the soda fountain in the back. At both stations, between customers, I wrote on yellow, legal-sized notepads, composing stories mostly on natural history and the outdoors. Back then in the early 1980s, a lot of Sutton’s regulars knew I wanted to be a writer, which made my stint at the drugstore slightly less humbling even as my tenure there stretched beyond my junior and senior years at UNC and into two years past graduation.

One day, Mary made an odd, but welcome offer: If I wanted a real place to work — to write — she would let me use her office on nights and weekends. It was on the second floor of what was called, in 1983, the Bank Plaza building. At the time, it housed North Carolina National Bank, and then Bank of America, and most recently — and ironically, as will become clear — a CVS pharmacy. (It’s empty at the moment.) Bank Plaza was a 60-second walk from Sutton’s. There was no charge, Mary said. All I had to do was clean the second-floor bathrooms every few days.

Mary was among the first in my extended Sutton’s family to recognize I wasn’t playing around with this writer thing. At the time, I couldn’t see the path forward, but I was willing to figure it out, to work it out, one sentence at a time. So, at Sutton’s and elsewhere, I wrote. Essays. Nonfiction. Short stories. Just get it down on paper — That’ll be $6.47, please — and don’t worry so much — Yes, we do, the cough drops are right behind you — about where the writing might go. It seemed like I wrote constantly back then. Of course, it seems like I write constantly these days, too, and have for 40 years.

T. Edward “Eddie” Nickens ’83 has been a writer for 40 years contributing to such publications as Audubon, Smithsonian, Our State, The Zebulon Record. Today he is contributing editor at Garden & Gun and editor-at-large for Field & Stream. Photo: (GAA/Cory Dinkel)

On many days I would leave Sutton’s at 5 p.m. and walk up Franklin Street to the NCNB building. Mary had a tidy, second-floor office, and she set me up with a small desk that held my IBM Selectric typewriter and an even smaller set of bookshelves hanging on the wall. There was a window that opened onto Franklin Street, from which I could look out at the grand sweep of Chapel Hill’s main drag during breaks. I was no Hemingway in Havana, but it wasn’t a bad deal for a twice-a-week, 20-minute round with Mr. Clean.

Sutton & Alderman

This July, Sutton’s Drug Store turns 100. Despite the fact that Google now identifies Sutton’s as a “hamburger restaurant,” the old-fashioned pharmacy was for most of its tenure a purveyor of tonics and prescriptions, cherry Cokes and cheeseburgers, Goody’s Headache Powder, boot polish, Copenhagen and a dizzying array of merchandise. If you needed a last-minute “blue book” for your handwritten exam, you could find one at Sutton’s. If you’d popped a button, blown a fuse or lost your lipstick, Sutton’s had you covered. The storefront at 159 E. Franklin St. is an icon only slightly less known, and perhaps no less beloved, than the Old Well itself.

The storefront at 159 E. Franklin St. is an icon only slightly less known, and perhaps no less beloved, than the Old Well itself. (Photo: Shelly Rivoli/Alamy)

The store was founded in 1923, as is displayed on the well-known Sutton’s Drug Store sign and logo, but that’s not the full story. What opened in 1923, just two years after the first pavement was put down on Franklin Street, in a brand-new building constructed by Robert L. Strowd, was a drugstore owned by James L. Sutton and his brother-in-law, Jacob Leroy Alderman (class of 1923). It was called, unimaginatively, Sutton & Alderman. This was a time when the nucleus of Franklin Street included a meat market, shoe repair business, department store, general stores, an A&P grocery store and the old Pickwick Theatre. Sutton & Alderman took over a space that had recently been vacated by “Jack” Sparrow’s old shop that specialized in “fresh fruits, smokes and newspapers.” Other tenants of the two-bay building included a cafeteria, a print shop and a cleaners. The Carolina Coffee Shop had opened a year earlier.

According to Neil Alderman ’83, grandson of that original J.L. Alderman, Sutton and Alderman lost Sutton & Alderman during the Great Depression. Neil Alderman believes the pair went their separate ways for a few years, and then, at some point, Sutton returned to Chapel Hill and reopened the pharmacy. His name has since carried the day, while the Alderman moniker has faded.

At least as it regards 159 E. Franklin St. Another Alderman relative was Edwin Anderson Alderman (class of 1882), great-great-uncle to Neil Alderman. Edwin served as president of three colleges — UNC from 1896 to 1900, then Tulane University and the University of Virginia. Alderman Residence Hall is named after him, as is the University of Virginia’s Alderman Library. Neil Alderman is proud of his family’s history on Franklin Street but figures there’s no need to cause a fuss over his ancestor’s name being excised from Sutton’s fame. Whenever the 1923 date comes up, he plays it cool. “I don’t say anything,” he laughs. “It’s just one of those little things I enjoy knowing. I just nod and keep on eating my hot dog.”

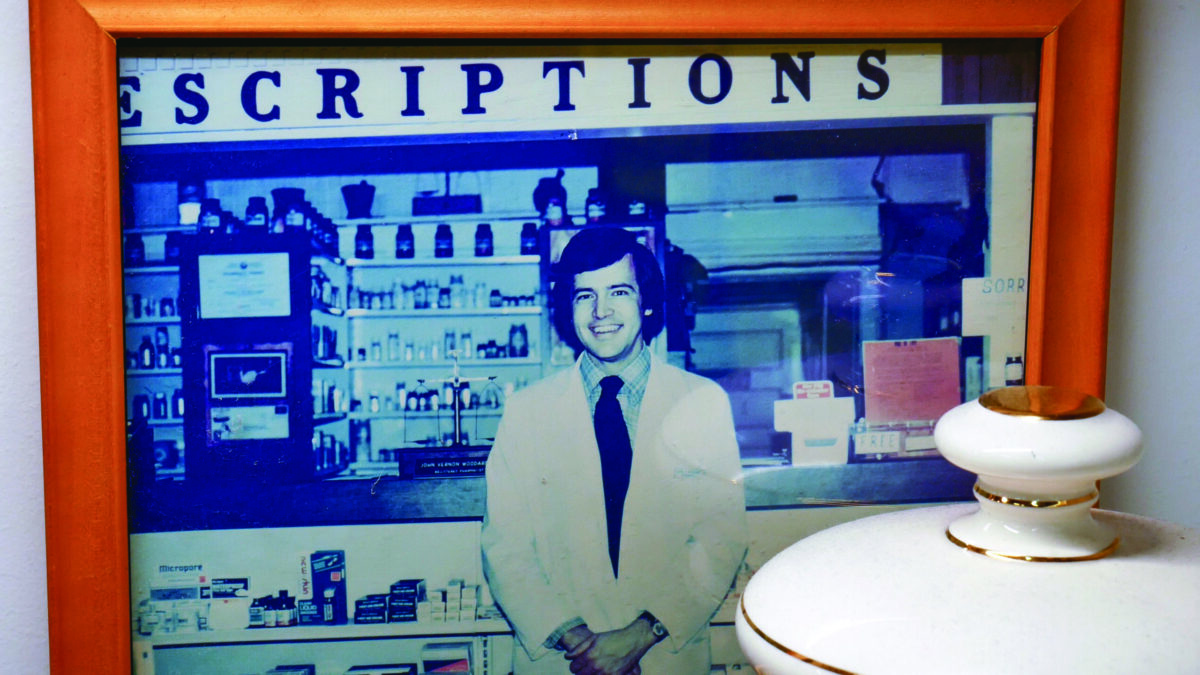

John Woodard ’68 said a drugstore was the last thing he ever wanted to own. Then Sutton’s came up for sale. Photo: GAA/Cory Dinkel)

It’s fair to say the modern era for Sutton’s Drug Store began in 1977, when a graduate of the UNC School of Pharmacy, John Woodard ’68, bought the store from another pharmacy school graduate, Elliott Brummitt Sr. ’55, who left pharmacy altogether to open his own jewelry store in the space below Sutton’s. At the time, Woodard was a pharmacist at Henderson Drug #2 in Henderson. One day a wholesale dealer told him of a small, independent drugstore for sale nearby. Woodard remembers the conversation well.

“We were friends,” Woodard said, his tall, lanky frame folded into a Sutton’s soda fountain booth, “and I’d always been clear that the last thing I ever wanted was to own my own drugstore.”

But his wholesaler pal sweetened the deal: What if I told you, he replied, that it was Sutton’s in Chapel Hill?

“I remember saying, ‘You son of a gun,’ ” Woodard laughs. “On Franklin Street. In the 100 block. That’s like hitting a home run. How could I say no?”

On his first day at work, there were 18 red stools perched on stainless steel pedestals at the lunch counter. Sutton’s’ cook, Willie Mae Houk, had already been working there for 21 years. Bill Dooley was in his 11th year as UNC’s football coach. Dean Smith had recently lost the NCAA national basketball championship to Marquette University. It would mark the beginning of a nearly 40-year run for the avuncular Woodard as, hands-down, Chapel Hill’s favorite pharmacist, and keeper of the flame of a kind of Franklin Street zeitgeist that is now in short supply.

Sutton’s nurtures a writer

Sutton’s owner, Don Pinney, and Eddie Nickens look through old photo albums. They didn’t find a picture of Nickens, but found plenty of shots of folks that Nickens remembered from when he worked at Sutton’s in the 1980s. (Photo: GAA/Cory Dinkel)

I worked at Sutton’s for four of the most formative years of my life, both as a college student and a college graduate with no clue what to do next. My time as a student at UNC ran from 1979 to 1983, with a few bonus years tacked on by refusing to leave the safe cocoon of Sutton’s. Working full time, after graduation, I cleared $124.46 a week, and I made every penny pushing the mint green and lemon yellow currency buttons on Sutton’s National Cash Register behemoth that looked like it could have been hauled from the wreckage of the Titanic.

This was the Franklin Street of yore, back in the day when much of the college-town strip west of Spanky’s Restaurant (R.I.P.) was nearly terra incognito, and you’d walk that far only for groceries at Fowler’s Food Store. Or to He’s Not Here, although peregrinations to and from that bar often were outside what most would describe as “walking.” Next door to Sutton’s was an office supply store where you could buy magical items such as telephone answering machines that recorded messages on tiny tape cassettes. Within a 2-minute walk of Sutton’s were an insurance agency, travel agency, dry cleaners, bookstore, florist and a couple of fine jewelry stores. (Raise your hand if you bought or wear an engagement ring from Wentworth & Sloan Jewelers. Mine is certainly up.) Back then, and for long before, Sutton’s was a hub around which much of Chapel Hill’s town business revolved. The mayor and half the city council had breakfast at Sutton’s every morning. It’s too easy to be mesmerized by the amber of those days, but it’s solid ground to say that, at the time, Franklin Street was more of a Mayberry than it is today, albeit a Mayberry festooned on weekend mornings with beer cans and the odd piece of clothing tossed on the sidewalk.

And as in every era, I suspect, there was a small group of students who worked part time in the shops and restaurants on Franklin Street. Ours formed a tight-knit group of insiders who reveled in the fact that we could stay after hours at the Rathskeller and dance with the waiters and that we knew all the shop merchants by first name. My friend Noel LeGette Morris ’86 worked at University Florist. Sharon McElveen ’82 at the office supply store; Ledbetter Pickard, beside Sutton’s Pals who worked at Sutton’s during my tenure: Eliza Bradfield Dale ’82, Tina Beckendorf and Eliza Sinclair Lucas ’84. A crew of us met every Friday at the Rathskeller for the Friday-only barbecue plate. Perhaps we imagined ourselves as sort of an ex-pat community, living part of our student lives deeply embedded in the business fabric of Franklin Street.

For sure we were adopted by Sutton’s old guard. Houk was the grand dame of the boulevard. The white-aproned and hair-netted short-order cook worked the flat top at Sutton’s for 32 years, until she had a heart attack and collapsed on the floor in front of the grill in 1988. During her funeral procession, Woodard recalled, at each stoplight was stationed a Chapel Hill police officer and a UNC police officer or Orange County sheriff’s deputy. I particularly loved Reuben Cole, Sutton’s longtime kitchen assistant. He had a thin Errol Flynn mustache and an impish sidelong grin. I drove a succession of beater cars at the time, and once a year I would slip Reuben a $20 bill on a late Friday afternoon. The following Monday, he’d hand me a brown paper bag inside of which was a bootleg car inspection sticker and a Mason jar of moonshine.

“My time as a student at UNC ran from 1979 to 1983, with a few bonus years tacked on by refusing to leave the safe cocoon of Sutton’s.” – Eddie Nickens ’83 (Photo: GAA/Cory Dinkel)

But what I mostly did at Sutton’s was write. Standing behind the front cash register, or sitting during the slow hours at the soda fountain counter, I wrote, often furiously. I wrote about the different kinds of ice I found one day on a frozen Jordan Lake. I wrote about frog calls and bird calls and fishing trips. In September 1983, I landed a gig at the Zebulon Record writing a weekly outdoors column. For “Field Notes” I was paid 25 cents per published column inch, which spawned a lifetime of verbosity that has irritated many an editor since. Six months later, I screwed up the courage to contact The Chapel Hill Newspaper’s sports editor, and he agreed to run “Field Notes” as well. For that, I was paid the staggering sum of $7.50 per column. Hot damn, I thought. Now I was a syndicated columnist. Sort of.

Writing those columns helped shape my voice and narrative style, but there was something just as important going on: The Sutton’s magazine rack was directly across the main aisle from the cash register, and every time I looked up, I could see scores of titles lined up in a kaleidoscopic display. These were the good old days of magazine publishing, and Sutton’s carried titles as niche as knitting magazines and as highbrow as The Atlantic and Harper’s. At work, I could leaf through their pages, and study point-of-view, pacing and structure. I soon learned to dissect a table of contents to see how magazines are constructed, and I began to recognize certain writers whose work appeared more frequently. Oddly enough, working the cash register and soda fountain at Sutton’s helped me see a possible road ahead as a magazine writer.

There were a few titles in particular I dreamt might one day publish my work: Audubon, Smithsonian, Field & Stream, Men’s Journal and Southern, perhaps the original publication to explore the cultural South. Some are dead and gone, winnowed away to nothing by the flight to digital media. Others have weathered the storm. Over the years, I would write for all of them, and many more. And every sentence I put together, every paragraph I’ve since constructed, has in important ways been rooted in those hours bent over a legal pad at Sutton’s, or writing late into the night at my janitor’s gig.

To be honest, my tenure at Sutton’s in the latter half of my time there became an increasing source of some embarrassment. I’d collected a journalism degree from one of the best programs in the country and had proven writing skills, but at graduation I simply wasn’t ready for a new reality of a real job in a new city. My bonus years at Sutton’s were an important waystation, where I worked through a few existential questions. We all take our own path, and in the creative realm, particularly, the road is often crooked and obscure.

In 1986, I took a full-time job at the now-defunct Spectator Magazine in Raleigh. I hugged Woodard and walked into a future I could barely conceive. I suppose that was not unlike the experience of any college graduate. I had simply taken a couple of redshirt years along the way.

Old photos and a pegboard

To cover a wall of ugly, grease-stained pegboard, John Woodard ’68 framed and hung a few black-and-white photographs of customers. That’s a little better, he thought. He could not have imagined what would happen next. (Photo: GAA/Cory Dinkel)

That same year, with the Sutton’s lunch-counter business booming, Woodard decided to expand seating at the soda fountain. In the mornings, breakfast patrons stood outside, waiting for him to open the doors. Students lined up along the lunch counter four and five deep, waiting for a seat. Woodard drove to a surplus store in Durham that he’d heard had a few old diner booths for sale. With him was a young Don Pinney — he’s now 58 years old — whose roots run deeper in Sutton’s history than even Woodard’s. Pinney’s father was a soda jerk at Sutton’s in the late 1950s and early 1960s. His mother ran the store’s beloved cosmetics counter. Pinney worked odd jobs at Sutton’s starting when he was 13 or 14, he said. He drifted in and out of school, but always found an anchor at 159 E. Franklin St., a place that increasingly felt like home.

Back on Franklin Street, Woodard and Pinney dragged away the merchandise counters that fronted the soda fountain counter and removed a long section of aged shelving from the facing wall. The used booths fit well enough, but the new arrangement left a wall of ugly, grease-stained pegboard exposed. Woodard and Pinney were stumped about a fix when Houk piped in from the grill. “Don’t you have some old photographs in storage?” she asked. “Maybe you could put those up to make it look a little nicer.”

Woodard trudged up the ancient wooden steps that led from the pharmacy counter to a dark loft storage area — a place I’d never even ventured into — and returned with 11 8-by-10, black-and-white photographs of athletes and customers who had been regular Sutton patrons over the years. He bought cheap black frames and hung the photos on the pegboard. That’s a little better, he thought. He could not have imagined what would happen next.

Today, Sutton’s has an archive of more than 10,000 photographs in storage. You can still have your photograph taken there, but there’s no guarantee that it will ever hang on the walls. Such is the price of success. (Photo: GAA/Cory Dinkel)

“Oh, my gosh, people went crazy over the photos,” Woodard recalled. Regulars clamored to have their photos taken with friends, with Houk, with Woodard and with a steady stream of UNC athletes that frequented the soda fountain. Woodard added more booths — some from a McDonald’s undergoing renovation — and the customers kept coming. Athletes such as UNC basketball greats Melvin Scott ’05 and Eric Montross ’94 showed up, as did Carolina standout linebacker Brandon Spoon ’00 and offensive guard Arthur Smith ’05, now head coach of the NFL’s Atlanta Falcons. Tyler Hansbrough ’09 had a favorite booth, one that mostly screened him from passing foot traffic and “gave him some peace and quiet,” Woodard said. Sometimes he was in Sutton’s twice a week. “He would sit with his back to the front door and gobble down five eggs and a chicken breast at every sitting,” he said.

But Sutton’s was no Rodeo Drive. It was a melting pot of every town and gown socioeconomic demographic in Chapel Hill. Sooner or later, most regulars wanted their photograph affixed to one of the some-three dozen photo collage posters that hang from Sutton’s ceiling like the retired jerseys of basketball greats.

Today, Sutton’s has an archive of more than 10,000 photographs in storage. You can still have your photograph taken there, but there’s no guarantee that it will ever hang on the walls. Such is the price of success.

A new owner

The 1990s and early 2000s brought about impressive growth for Sutton’s the restaurant, but not so much for Sutton’s the pharmacy. National chain prescription stores were steamrolling downtown pharmacies everywhere. A Walgreens opened in Franklin Street’s downtown district, taking a bite out of Woodard’s business. In 2014, a CVS opened in the old Bank Plaza building, where I’d mopped toilets and mixed metaphors so many years earlier. Its impact was even more serious.

Woodard saw the writing on the prescription bottle. The historic pharmacy-slash-soda-shop seemed ever more an anachronism, a magical pumpkin that even such a magical place as Franklin Street might not be able to keep in business. Gone was the office supply store next door. Gone was the insurance agency, the travel agency, Elliott Brummitt’s jewelry store, Wentworth & Sloan. The hub of Franklin Street activity was shifting ever westward, like manifest destiny, past Columbia Street and coalescing in the vale beyond Granville Towers.

That year CVS bought Woodard’s pharmacy operation. It bought all the over-the-counter medicines in the front of the store and all the prescription drugs in the back. But what CVS really wanted, Woodard said, was his prescription files: The names and data of all the customers Sutton’s had served and nurtured and tended to in its last decades.

The deal left the soda fountain intact, but Sutton’s hobbled. Woodard was crestfallen. “You could see it on John’s face,” Pinney recalled. “His baby was gone.”

Woodard agreed to work at CVS for a bit, to provide a transition for customers accustomed to his friendly, avuncular, impossible-to-ruffle demeanor. He lasted a month, then hung up his white coat forever.

When Woodard retired, he turned Sutton’s over to Pinney, who had long evolved into a friend as much as a business partner. “We never really had that conversation of what was going to happen,” Pinney said, “because we never had to have that conversation. John knew I loved Sutton’s like he loved Sutton’s.”

Don Pinney’s roots run deep in Sutton’s history. His father was a soda jerk at the pharmacy in the late 1950s and early 1960s. His mother ran the store’s beloved cosmetics counter. Don worked odd jobs at Sutton’s starting when he was 13 or 14, he said. He drifted in and out of school, but always found an anchor at 159 E. Franklin St., a place that increasingly felt like home. He took over the business when John Woodard ’68 retired. (Photo: GAA/Cory Dinkel)

With a bit of glee, Woodard points out that both the Walgreens and the CVS, which eviscerated the homegrown drugstore, have vacated downtown Chapel Hill. A non-compete clause prohibited Pinney from selling items that CVS sold, so he moved toward private-label jams and jellies and penny candy, and snacks with a North Carolina connection such as Chapel Hill Toffee. He can hardly keep them in stock. “I beat them at their own game,” he said with a satisfied grin.

In fact, Pinney has proven himself a particularly astute businessman. He opened a Sutton’s Drug Store satellite soda fountain counter at Chapel Hill’s Europa Center off Durham-Chapel Hill Boulevard and a Sutton’s Drug Store restaurant in the historic Wrike Drugs building in downtown Graham. He’s turned Sutton’s into a much-desired, special events space. Morehead-Cain holds fundraising events there, and fraternities and sororities rent out the space for private parties. During exam weeks, some sororities open accounts at Sutton’s so members can grab a quick bite to eat. Sutton’s has hosted wedding parties with an orchestra, candlelit tables and prime rib on the menus. One customer rents out the space for every UNC-Duke basketball game.

At its 90th birthday party, Sutton’s offered hot dogs, Cokes and french fries at 1923 prices: a nickel each. Pinney ordered 1,500 hot dog buns and had his bread supplier on call to deliver more. Five years later, on its 95th anniversary, a complete meal — hot dog, fries and a fountain drink — cost 95 cents. Pinney bumped it up to a whole dollar for the 100th anniversary.

“You wouldn’t believe what goes on in here,” Woodard effused. “It’s incredible what Don has been able to do.”

During the coronavirus pandemic, Pinney came close to shutting Sutton’s doors. A few steps down the street, Ye Olde Waffle Shop couldn’t make it, closing in December 2020 after 48 years in business. But Pinney’s ingenuity and the generosity of customers staved off the padlocks. Sutton’s provided house meals for the Phi Gamma Beta fraternity during the pandemic. Pinney didn’t pay himself for months, and he never laid off an employee. His customers responded in kind. One student opened a GoFundMe account to save Sutton’s. Athletes such as All-American Tar Heel basketball forward Brice Johnson ’16 weighed in with encouragement. The effort had a goal of $10,000. It raised more than $30,000. A similar effort in Canada, by a former employee, brought in another $10,000. “That’s what kept me afloat,” Pinney said. “Even today, I can hardly believe it.”

Here to stay

A photo of Pinney and Woodard greeted dozens of people who lined up for $1 hot dogs and commemorative T-shirts on April 12 in celebration of the store’s 100th anniversary. (Photo: UNC/Jon Gardiner ’98)

There has been a slew of rumors going around that Sutton’s is closing after its 100th anniversary. Pinney is adamant it won’t. The rumors are likely based in the challenges Sutton’s faced during the coronavirus pandemic, but a visit during any midday lunch period will put to rest concerns that a place like Sutton’s is a relic of the past.

In 1923, the original announcement for Sutton & Alderman promised “a fine soda fountain of the most modern type, and plenty of tables.” I suppose one might say it was the soda fountain that carried the day for the first iteration of Sutton’s Drug Store, as it is the soda fountain today that keeps the lights on at 159 E. Franklin St.

But that’s not entirely true, either. While market forces are powerful drivers, there are instances in which passion might actually trump a business plan when it comes to making a business work. Woodard poured 40 years of his life into Sutton’s Drug Store, 70 hours a week at a time. He bought a pharmacy, but he had inherited a legacy. And he was smart enough to hand it over to a native son with a preternatural facility to meld past and present into a thoroughly modern entity.

My own cherished memories of Sutton’s are a personal snapshot in time, like the photographs of all those Sutton’s regulars, decked out in add-a-bead necklaces, rugby shirts and other fashions of times gone by. For a few short years, Sutton’s was my safe place, which I clung to until I was ready for a larger world. It’s where my own story began, in large measure, which turned out to be a story I couldn’t have imagined despite all those hours I dreamed behind the counter at Sutton’s.

Many is the time I’ve thought: My Sutton’s story really is one of a kind. Maybe I’ll write it one day.