The Missionary

Shirley Ort knows what it’s like to grow up without the luxury of dreams. Her razor-sharp acumen for the complex world of financial aid has made Chapel Hill nearly peerless as a place of opportunity.

by Beth McNichol ’95

She was prepared to leave her job at UNC in the summer of 2014. It was not the policy changes taking place in the UNC System, nor the too-long drumbeat of an academic and athletics scandal. She certainly wasn’t ready to retire; Shirley Ort’s mind is a deep well of intellect fitted with a ladder of insatiable curiosity, and she thrives on using it to help others.

Shirley Ort and Solo (Photo by Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

It was friendship. Friendship was the reason she wanted to leave. And friendship was the reason that she ultimately stayed.

Ort oversees $400 million in financial aid services as the associate provost and director of Carolina’s Office of Scholarships and Student Aid, a role that is quietly crucial to shaping the student body. She is quite simply higher education’s most respected expert in the field, an innovator who, for the past 18 years, has built Carolina’s enviable reputation for access and authored policies that help UNC students graduate with one of the lowest average debt burdens anywhere. In the increasingly important world of student aid, she’s a bit of a rock star, albeit a reluctant one who prefers pashminas and Prosecco to sequins and the spotlight.

But all great rock stars have their indispensable backup singers, and for Ort, that person was an incomparably clever professor of Romance languages named Fred Clark.

Clark taught Portuguese and Brazilian theater at Carolina for 47 years, and he knew how to warm up a crowd. As the academic support man for the Carolina Covenant, the University’s no-loans aid program for students from low-income families who gain admittance, Clark directed a host of mentoring and programming services, shoring up scholars’ self-esteem and answering their calls no matter the time of day or night.

But Clark had a tendency to become gloomy in the early hours of each day, as he waited for the world to yawn and stretch and adjust to his anxious energy. One day in 2006, he had a proposition for Ort, with whom he had become friendly.

“Would you mind,” he ventured, “if I came over to your house for coffee in the mornings?”

Thus started a daybreak routine for Ort, who has never married, and Clark, who was gay and also single. After three weeks, Ort handed him a key. And each morning for the next eight years, Clark let himself into Ort’s townhouse, took her dog for a walk, read the newspapers and made the coffee while he waited for her. When she came downstairs, Ort would join Clark in reading the news, and the two would begin to solve student aid problems before they arrived at their offices in Pettigrew Hall. Three nights a week over dinner, they did the same.

Clark would tell Ort the stories of Covenant scholars who were struggling with classes or family or confidence; and the buoyant and snowy-haired Ort, who created the widely lauded Covenant, would bring to bear her knowledge of resources, her creative puzzle-solving and her extraordinary heart.

They comprised one of higher education’s most productive coffee klatches, one sip at a time helping thousands of young people — many of them first-generation college students, as Ort and Clark had been — to take one foot out of poverty and place it in the sphere of possibilities through a UNC degree.

Along the way, Ort and Clark became exceptionally close.

“I’ll tell you,” Ort said, “when you’re a woman of my age, and you have a good friend who likes to go to T.J. Maxx and is also a good cook, who will be your escort anywhere … It was just a deep, deep friendship.”

When Clark fell ill in June 2014 with lung cancer, Ort took him into her home full time and managed his medications and made his visitors comfortable. It was difficult palliative work, a job in itself, but one that she welcomed.

“There is nothing more sacramental than helping someone you love transition when there is no fight,” she said.

One day, Ort told Clark, who had been given a few months to live, that she was ready to leave her job to focus on his care.

“No, don’t do that, don’t do that,” Clark pleaded with her. “Really, don’t do that. You’re going to need the structure of the workplace, you’re going to need your friendships, and you’re going to need the purpose of work.”

“And he was right,” Ort said.

Ort conceived the Carolina Covenant and, to make its heart beat, she brought in Fred Clark, a shrewd match that showed what she had learned from the people who had opened opportunities for her. Their professional journey led to an extraordinary friendship. (Photo by Kasha Mammone/The Daily Tar Heel)

Near the end of his life, Clark worried about the students he was leaving behind, the way a parent worries about what will become of his own children when he’s gone. He worried that the powers that be — some of whom already were moving to limit policies that supported access — would abandon their low-income engines-that-could. He asked Ort, “What happens if, when you’re gone, and I’m gone, they don’t care about the Covenant in the same way?”

“We don’t need to worry about that,” she replied. “Because really, whoever the future ‘theys’ are, you can’t take away what we’ve already invested in all those kids.”

About 5,000 students have been helped by the Covenant, whose scholars have an average family income of about $25,000. The four-year graduation rate for students who qualify for the Covenant (at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level) has grown from a pre-program benchmark of 56.7 percent in 2003 to 80.2 percent in 2015. That’s dazzlingly close to UNC’s overall graduation rate of 83.8 percent, and it’s proof that the doors of promise can be flung wide open no matter one’s background.

(Clark is mentioned in the Wainstein report on UNC’s academic-athletics fraud case as having advised students “to consult with the [former department of African and Afro-American studies] to see what courses were available, as he knew that the AFAM courses were not overly taxing and were popular with students.” Based on an interview with Clark, who held administrative positions in academic advising and the General College and became associate dean of academic services in 2008, the report said that he “was aware of the AFAM paper classes at the time that they were offered; his understanding was that they were courses that required a long paper and did not require attendance. Clark explained that professors do not question other professors’ courses and that so long as a department was offering a course, it was a legitimate course.”)

More than a year has passed since Ort lost Clark, and now, she says, it’s time she left Carolina for good. Time, because managing life at UNC without Clark has been heartbreaking. Time, because she will be 70 in April, and she believes that number begs the start of a new chapter. Time, because Shirley Ort — a farm girl from Michigan who arguably has done more to expand and protect what it means to be a Tar Heel over the past two decades than just about anyone in Chapel Hill — trusts that the “future theys” will safeguard what she, Clark and her staff have built.

Shirley’s angels

“Isn’t this a great view?” Ort asks in her elegant, lilting voice of the scene outside her Pettigrew Hall window. Ort’s office is modest, but the world beyond it is indeed spectacular, an October burst of yellow and orange across the expanse of McCorkle Place, with ruddy brick walkways crisscrossing the fading summer grass, all paths paved with opportunity. This view was unthinkable to Ort at 17, a world of higher consciousness closed to a girl from an impoverished rural family.

Ort’s father, Victor, was a tenant farmer in small-town Hillsdale County, Mich., and her mother, Edna, was a cook; both had eighth-grade educations. In their town of 500 people, they never earned enough money to own a speck of the soil beneath their feet.

“We learned to live with adversity from our parents,” Shirley’s younger brother, the Rev. Larry Ort, a pastor and college professor in Brookings, S.D., said, “and we definitely knew what it was like to work hard because of them. We were used to it.”

Shirley spent her childhood cooking with her two sisters for hired men on the farm and, in the summers, for the “strapping, good-looking guys from high school” who baled the hay. No one ever asked, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” Even dreams were a luxury.

“My aspirations were normed by my immediate family and by my community, and they were really pretty low,” Ort said. “At the same time, they were pretty high, because I wanted to be a good person and to help other people. But in terms of sophistication? No.”

Shirley and Larry were especially close and encouraged each other’s learning. As the only girl in a high school chemistry class in 1963, Shirley recalled the teacher asking her why she was not in the home economics lab instead. She said, “I’m in this class because my brother’s here.”

“And that was not a feminist statement,” Ort recalled. “I didn’t know what feminism was. It was the truth. We were 15 months apart and joined at the hip. We did everything together.”

Most kids from Camden-Frontier High were not college-bound, and Shirley, despite her golden grades, never considered it. She had a job lined up as a bank teller, and that was a pretty good gig for a girl in Hillsdale.

As a senior, Ort finally had plans to go to college. (The Hillsdale Daily News, 1963)

Her high school principal became the first of many people in Ort’s life who would invest in her possibilities. Call him Angel No. 1. When he discovered her plans, he brought an application for Spring Arbor University to the Ort farmhouse and encouraged her to apply. If they accept you, he said, they’ll find a way to help you stay enrolled. With her parents’ blessing and no financial help — the federal student aid program would not begin until the following year, in 1965 — she went.

College was a frightening and exhilarating place.

“It was hard,” said Ort, who majored in history, “because I had so much to learn. I couldn’t get my head around what a credit hour was — that’s a foreign concept. But it was also magical. … I loved the discovery and the rigor of it, even though I was terrified all the time. And I kept thinking about the juxtaposition of what I got to think about in college and what I would have been thinking about if I had stayed in the bank. That was not lost on me. The privilege of studying things that were not immediately related to what I had to do that day really registered with me.”

To pay for that privilege, she worked full time while going to school full time, holding a variety of low-paying jobs. She graduated with honors in four years, she graduated “very tired,” and she graduated $6,000 in debt, or about $36,000 in today’s economy. That sum would have been greater if not for the help of a mystery benefactor who deposited $80 in her account each semester of her junior and senior years. Ort still doesn’t know who Angel No. 2 was.

Because she was not working toward a nursing or teaching degree or else getting engaged — the most popular roles for a woman in the 1960s — a professor advised Ort to gain some “salable skills” while she pursued her studies. It was good advice; the on-campus jobs she took while she earned a master’s in medieval history from Western Michigan led to a full-time position in student affairs at Seattle Pacific University. Soon after, she became dean of students there.

Higher education became her purpose, a place in which she could have a future of great depth while honoring her humble past. By 1979, when Ort became deputy director for student aid at the Washington State Higher Education Coordinating Board, it was clear that her calling in life would be to give students who grew up like her a chance.

“Most of us are missionaries at heart,” Ort said of her profession. “There are a lot of us in student aid who are first-generation, who are working in the field because of our own reflection and gratitude for where we were able to go.”

Creating the linchpin

Ort was open to whatever piqued her curiosity, from the law degree she earned from Seattle University in 1986 while balancing her day job to the Mary Kay license she got in 1995 for avocational fun; she often used it to “play makeup” with troubled teens she visited through Washington state outreach programs.

She was doing work she loved in the Pacific Northwest and had no desire to leave. So, of course, opportunity came courting.

Enter Angel No. 3: Elson Floyd ’78.

Floyd, who had returned to Chapel Hill as executive vice chancellor, knew Ort from his days leading the Washington coordinating board. In 1997, Carolina needed a student aid director, and Floyd was convinced that person should be Ort.

Ort was nearly as determined that Floyd was wrong.

She canceled her first interview in Chapel Hill. Ort was accustomed to the dynamism of a state agency that worked with many types of institutions, and she worried the Carolina job would be too narrow.

Floyd, on the other hand, “was really quite certain,” Ort said, “because he knew what I cared about, he knew what Carolina cared about, and he could see the magic. He was so bright.”

Shirley Ort at home. (Photo by Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

Ort said Floyd, who died last year at age 59 after leading Washington State University for eight years, knew that she and Carolina were the right match for UNC’s future goals — not just its longstanding commitment to being “as free as practicable” to the students of the state but how that principle could be applied to fit the economic realities of the day.

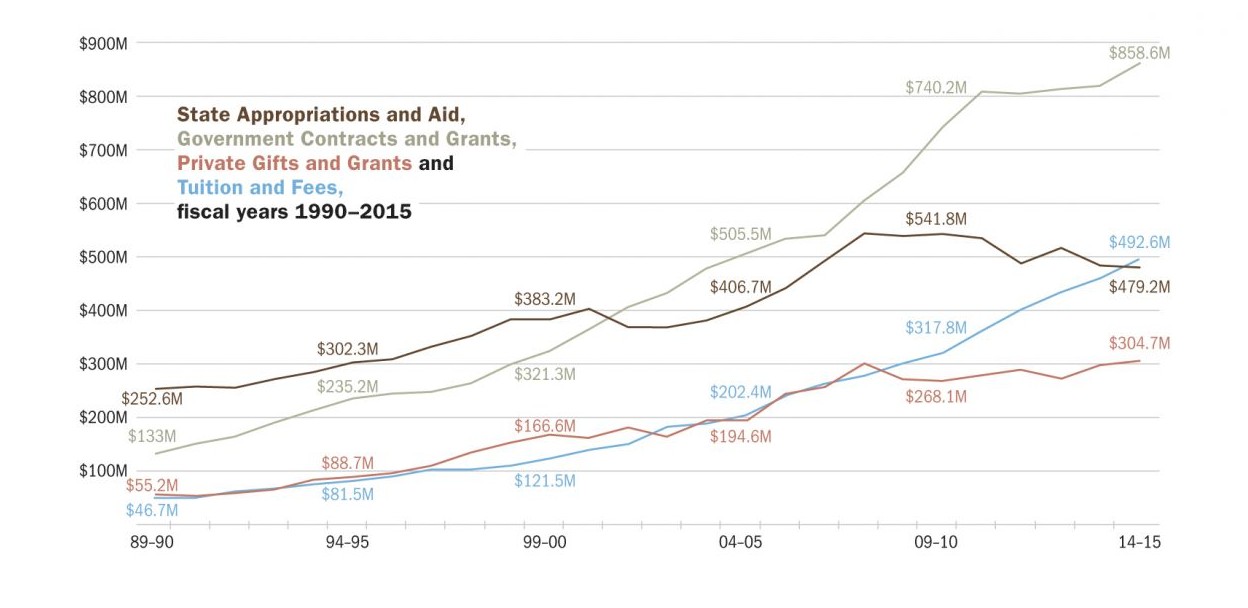

“When I came, the mantra here, as it was in a lot of places, was that low tuition is the best form of financial aid. That served North Carolina really well for a long time. But I can remember coming in and realizing, given the socioeconomics and demographics here at Carolina, that low tuition was the best form of financial aid for affluent families.”

Significant shifts in thinking already were in play when Ort arrived in 1997; Carolina and N.C. State had worked together to secure permission for a tuition increase to bolster lagging operating revenues, and the focus became how to protect low- and lower-middle income families from being shut out of affordability as a result.

Floyd, Chancellor Michael Hooker ’69 and the trustees asked Ort to solve the puzzle.

Carolina is unusual among universities in that it gives its financial aid office the freedom to create policy, and that’s where Ort shone.

She dialed in to her experience and borrowed from a Washington state statute that allowed a percentage of all new tuition revenue — not gross, but the additional revenue from a tuition increase — to go to needy students. Ort reinterpreted it for campus-level use at Carolina so that an automatic escalator existed for student aid money whenever the tuition burden increased.

“At Carolina, we were able to do that for 15 consecutive years in a way in which no needy student ended up paying that tuition increase,” because they received grant money to cover it, Ort said.

Ort said the policy is the linchpin of what the University has accomplished over the past two decades, and it’s what sets Carolina apart from its public peers. Because of it, there’s been no real change in terms of constant dollars to student indebtedness over Ort’s tenure. Carolina meets 100 percent of financial need for its students through grants, scholarships or loans, or a combination of the three. Nationally, college students who borrow graduate with an average of $28,950 to pay back, but Carolina students clocked in at $19,042 last year — and there are fewer of them, too, as only four in 10 UNC grads who borrow leave Chapel Hill with debt, while 7 in 10 do so nationally.

“That policy worked very well for 15 years,” Ort said, “until August 2014.”

That’s when the UNC System Board of Governors, worried that middle-income taxpayers were shouldering too much of the burden for needy students, voted to limit to 15 percent the amount of tuition that system schools could devote to need-based aid. At Carolina, where 20.9 percent was going to needy students, including some from middle-income families, it amounted to a freeze — and a yank at the crucial linchpin.

How Carolina’s Funding Sources Have Changed: Seven years ago, government contracts and grants overtook state appropriations as UNC’s top revenue source; as of 2014-15, tuition edged above state appropriations for the No. 2 spot. (Source: UNC Finance and Accounting)

Her staff knew what such a change could mean: Student indebtedness at lower incomes could climb to $33,000. Access would take a hit. Ort was displeased and said so publicly, rankling the BOG, which called Ort and several other administrators in to reprimand them for their criticism.

“We were all very concerned [about the cap] …” Ort said. “Because we had done the analysis — we had a briefing paper that we never surfaced because it wasn’t welcomed, really — so when pressed to talk about it, we did. That angered them.”

Ort added that “the University has responded by making that [deficit] up, from sources other than tuition. I didn’t know they could do that, I didn’t know how they would do that, and I don’t know if it’s sustainable.”

Despite the policy setback, Ort said she is more optimistic than she was a year ago.

“Everything I hear affirms that we claim our history and our tradition and want to interpret that to new generations. So that causes me to think that there will be innovations that I might not even be thinking about today, that will carry that forward.

“It’s also being secured in a special, kind of curious way right now. Because given the problems with athletics and academic integrity, we’ve turned to what we’re sure of as the better part of ourselves to reaffirm [our values]. And in a way, that’s helping to tether what we care about — what I care about — in terms of inclusion and access and affordability as well. You hear that in almost every speech [Chancellor Carol L. Folt] gives, too.”

The Carolina Covenant currently has an endowment of about $9 million, and Ort’s office on the whole benefited from an extraordinary $447 million fundraising year for Carolina in the past year, receiving $12.75 million after setting a goal of $8 million. That was on the heels of pulling in $6 million the year before. This year’s goal is $20 million.

The reasons for the increases in private giving are many, Ort said.

“One of them is mindfulness on the part of the University,” she said. “Maybe the action of the [BOG] was the catalyst we needed to be more self-reliant and forward-thinking, because certainly, especially under David Routh [’82, vice chancellor for University development], we’ve had extraordinary leadership in that area. And we’ve been helped a lot by the national awareness of college costs.”

Awareness of cost barriers may be hyper-focused in this election year, but Eric Johnson ’08, Ort’s assistant director for policy analysis and communications, noted that it’s long been on his boss’s radar.

“The world has come around to where Shirley was 15 years ago and being focused on need-based access,” Johnson said. “That’s gotten to be a much more prominent topic over the last few years, in part because the economy went to hell and in part because tuition has gone up even at public colleges, but also just because we’ve started to notice that college is now a barrier to lots of people when it’s supposed to be an engine for opportunity.”

The investiture

Ort’s forethought and empathy make her revered among her colleagues and a popular speaker and workshop leader. Outside of her work at Carolina, she is vice chair of The College Board’s trustees, where she has influenced the SAT organization’s increased commitment to access, such as recently announced free online test-prep services and college application fee waivers for the underprivileged.

Eric Johnson mirrors Ort’s own clear-headed acumen for understanding many angles of the financial aid puzzle. But it’s no stroke of luck that he works for Ort; she kept a corner office in Pettigrew vacant for two years while he worked elsewhere, just waiting for him to become available.

“My lesson from Elson [Floyd],” Ort said, “out of gratitude, is that sometimes we have opportunities as educators to broker those good things for other people — if you’re paying attention, and you know this context and [how they fit with] that person’s abilities.”

That’s precisely how Fred Clark became the heartbeat of the Carolina Covenant. Ort intercepted him as he left another role at the University and plugged him into a position she knew was tailor-made for his talents.

That gesture is similar to what Ort calls “the investiture” — the act of helping someone see a better future for themselves, the way her high school principal did for her.

“It’s a great gift,” she said. “[College] is a hard age for students, a transitional period, and there’s a lot more self-doubt and lack of confidence. And there’s great power in conversations that help students see themselves in a broader, bigger role.”

In many ways, the Covenant, which Ort proposed to Chancellor James Moeser initially as a way to communicate that Carolina was within reach to low-income families, is one long version of that conversation. It’s the investiture, writ large.

Safe to say the message has been received; 14 percent of this year’s first-year students are Covenant scholars. And its impact can be drilled down to show improvements in specific demographics — for example, graduation rates for African-American men who are Covenant students have jumped 35 percent, an increase that’s greater than the program’s whole.

The success of the Covenant, which includes a 10- to 12-hour-per-week work-study commitment, has raised the question: Is it the money that makes the difference, or is it the programming that the Covenant offers — the mentoring, etiquette classes and progressive caring, the sense of belonging and depth of experience that scholars’ wealthier peers are more likely to find without guidance? Is it the Fred Clark-ness with which it is imbued?

Moeser believes it is a central factor. “Early on, it was Shirley’s idea to issue an invitation to faculty to volunteer to be mentors to these students,” he said. “That’s where I’ve heard so many stories of students whose academic success is attributable to the Covenant.”

Two years ago, Ort created Achieve Carolina to find out. The program extends those Covenant-like interventions to students at 300 percent of the poverty level to see whether their stagnant graduation rates also will improve.

“It’s too soon to know,” Ort said, “but it’s fun to work in a place where you can experiment.”

Ort leaves a university that meets 100 percent of financial need for its students, and those students who borrow graduate almost $10,000 below the national average of indebtedness. (Photo by Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

The pilot program will run four years, so Ort won’t be on campus to see its results. She is still a member of the Washington state bar and is considering a return to Seattle to raise funds for the King County Adult Drug Diversion Court, a job a good friend and Superior Court judge has suggested.

“I’m still sort of feeling it out,” she said, which in Shirley-ese has meant earning 18 credits she needed toward licensure last summer at the national drug court conference and “just hanging out with the judges and social workers to see how it feels. I wouldn’t want to do that unless I could own it emotionally as well.”

And if not?

“A lot of what comes to us is what we’re ready for and what we’re mindful of and what we’re open to,” Ort said. “So it’ll be an adventure.”

Stephen Farmer, UNC’s vice provost for enrollment and undergraduate admissions whose work is so closely tied to hers, said: “You can’t overstate the impact Shirley’s had on this place, this University being recognized as a place of opportunity. Shirley leaves this place just incalculably better than she found it.”

Now begins the Herculean task of finding a new Shirley Ort, who said her job description sounded so good that, were she 51, she’d apply all over again.

Carolina could use a time machine about now.

Beth McNichol ’95, a freelance writer based in Raleigh, is a former associate editor for the Review.

Since 1996, each March/April Review has covered admissions. It’s all online in the Review archive.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.