‘They Carry a Heavy Burden’

The movement to get William Saunders’ name off a classroom building has gained momentum toward an expected decision in May.

by David E. Brown 73

For a trustees meeting, it was an afternoon filled with startling words. Alston Gardner ’77, chair of the University Affairs Committee, assuring a group formed around the concerns of students of color that, indeed, they belong here (the group had asked); then Gardner reciting the breathtaking words of industrialist Julian Carr (class of 1866) at the dedication of the Confederate soldier statue in 1913, “citing his pride in having ‘horsewhipped a Negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds.’”

Student members of the Real Silent Sam Coalition recited, too — racist comments, written by their Carolina classmates on the social media app Yik Yak, and the names of those with white supremacy in their backgrounds for whom UNC buildings are named.

“It’s quite obvious to most people studying or working within the UNC System that the history of North Carolina reflects the history of the United States. It is good, it is bad and, at times, has been very, very ugly,” said Deborah Stroman ’86 (MA), a member of the business school faculty and president of the Carolina Black Caucus. “And sadly, many can live most of their lives happily in America, never really learning the real history of our great country.”

Carolina juniors Jaslina Paintal and Anisha Padma and senior Danielle Allyn hold signs during the March 25 meeting of the trustees’ University Affairs Committee. (Photo by Travis Long/News & Observer)

History Professor Jim Leloudis ’77 (’89 PhD) gave a statesmanlike lesson, which his students pay to hear, on Reconstruction and Jim Crow in North Carolina. He finished by saying that these students of 2015 — who insist their troubles didn’t end with the Emancipation Proclamation or Brown vs. Board or the sit-ins or the approval of the Stone Center for Black Culture and History — “carry a heavy burden.”

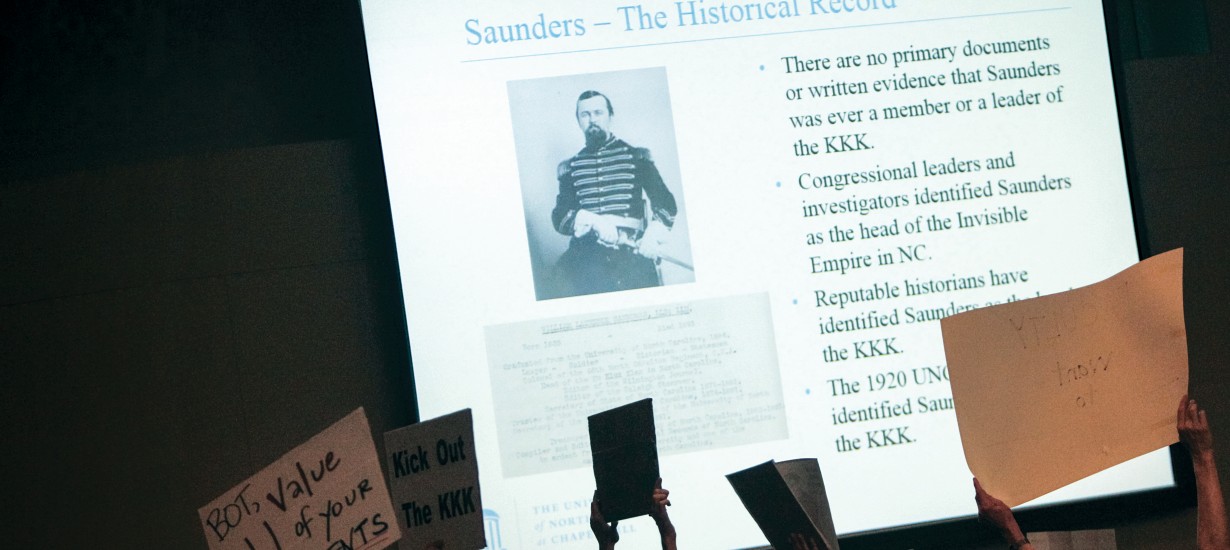

For two hours, the committee listened to eight invited speakers who were evenly divided about whether to scrub a 93-year-old classroom building clean of the name of William Saunders, a member of the class of 1854, soldier, political leader, historian, fellow trustee and now generally acknowledged to have been a leader of the Ku Klux Klan.

In the audience of maybe 100 that March day, among the usual cast of University administrators, were students the trustees had provided with buses to the off-campus site. They chanted briefly, groaned some and repeatedly snapped their fingers in a less-interruptive form of applause.

Borrowing from advice he’d received since a year ago, when he and fellow trustee Charles Duckett ’82 started studying the issue of the question of an unprecedented renaming, Gardner suggested there are three very different perspectives from which to view Saunders Hall and the 10 or so other buildings on campus named for people whose legacies include ties to white supremacy along with the famous Confederate statue of McCorkle Place: the time that is being memorialized; the date the edifice was erected; and the present.

To the students, the last of those is all that matters. “This movement is about the future of this University. It is about facing the violent racial history of UNC-Chapel Hill, the state of North Carolina and of the United States,” said senior Dylan Mott. “It is about this institution actually taking action against racism and violence. … The fact that the Board of Trustees at the time believed that that was a meritous [sic] act is for us evidence enough that [the] Saunders building needs to be renamed.” (Mott’s reference was to the fact that the information available to the trustees in 1922 when they approved the naming included Saunders’ attribute as “Head of the Ku Klux Klan in North Carolina.”)

The trustees agreed in March to extend their research, and they reached out to the public on a website. A few days later, Duckett made a specific plea to the faculty to weigh in. The full board is expected to announce a decision in May on whether to delete Saunders’ name. Should it choose to rename, another debate could emerge on the replacement.

Jordan Walker ’14 expresses the Real Silent Sam Coalition’s take on renaming Saunders Hall for author and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston: “We Are No Longer Asking.” (Photo by Travis Long/News & Observer)

The Real Silent Sam students are convinced it should be that of Zora Neale Hurston, the anthropologist and writer of the first half of the 20th century who studied briefly — and in secret — in a theater class taught by playwright Paul Green ’21 in 1940. That choice likely would have to go through the University’s detailed vetting process for such honorees. There’s been little talk of alternatives. Arch Allen ’62 (’65 LLBJD), chair of the Pope Center for Higher Education, spoke at the March meeting and suggested the building be renamed for William Holden, who was impeached and removed as the state’s governor in 1871 for his efforts to fight the Klan.

Letters to The Daily Tar Heel generally have supported renaming. Faculty and staff in the two departments in Saunders, geography and religious studies, are for it. Student body president-elect Houston Summers said he will make it a priority of his administration.

‘I am convinced that scraping his name from the facade of the building would represent a cowardly step toward erasure of our shared history. … As unsettling and painful as that history might be, we owe it to future generations to understand why that building bears Saunders’ name.’

Sam Fulwood ’78, Center for American Progress

The eight speakers said “yes” and “no” to renaming, but their strongest comments emphasized an entirely different level of education about UNC’s history and its collective present with regard to race.

Before joining the Center for American Progress, Sam Fulwood ’78 worked for three decades in journalism, including with the Los Angeles Times, where he created a national race-relations beat; his articles were part of a package that won a Pulitzer Prize for the Times’ coverage of the 1992 Los Angeles riots following the Rodney King verdict. Fulwood, who is African-American, told the trustees at the March meeting: “I strongly believe that it should continue to bear his name, with prominent explanation and historical contextualization as a signal history lesson for future generations. I am convinced that scraping his name from the facade of the building would represent a cowardly step toward erasure of our shared history.

“As unsettling and painful as that history might be, we owe it to future generations to understand why that building bears Saunders’ name. The history embodied by Saunders Hall stands less as an honor to a reputed Klansman and more as a marker of what we have overcome.”

Law professor Eric Muller agreed.

“The best way for us as a leading research university is not to remove Saunders’ name,” he said, “but to make Saunders Hall into a site that teaches future generations the disturbing lesson that Carolina was built not just on the excellence of a William Friday but on the ugliness of a William Saunders.

“By simply renaming Saunders Hall we might do a brief service to our own generation, but it would soon be forgotten, and we would squander the chance to educate ourselves and our children and our grandchildren about aspects of Carolina’s history that many would rather forget.

“So my argument is not to remove the name of William Saunders, but to turn the building named after him into a site of provocation: A provocation to remember the ugliness and not just the excellence in Carolina’s history, a provocation to reflect on how the advancement of our beloved institution was often entangled with human suffering, and a provocation to each successive generation — our own and future ones — to ask ourselves the uncomfortable question of who among us deserves celebration and who does not.”

‘The actions carried out by the Ku Klux Klan, of which he was an integral part, can only be described as acts of terrorism against fellow Americans.’

Frank Pray, a sophomore and president of UNC’s College Republicans

Among those who favor renaming, the word “terrorism” often is mentioned.

“Saunders was not simply a man who held prominent racist beliefs of the time period,” said Frank Pray, a sophomore and president of UNC’s College Republicans. “He was a man who took those beliefs and translated them into horrible actions that most individuals, even during that time period, knew were unacceptable. The actions carried out by the Ku Klux Klan, of which he was an integral part, can only be described as acts of terrorism against fellow Americans.

“The Klan’s use of terrorism was clearly something that is not only considered unacceptable in modern standards but was considered equally negative during the time period in which he lived. This is the key factor that makes the naming of Saunders Hall objectively different from the naming of other buildings on campus, such as Spencer and Aycock.”

‘If the options were simply to remove the name or to leave it, I would vote in an instant to remove it, for reasons you’ve heard today. … I’m drawn to a third option, and that is the option to curate and bring scholarship and bring teaching to bear on Saunders Hall and other contested spaces across our campus.’

Jim Leloudis ’77, history professor

The UNC library’s Virtual Museum of University History identifies 10 people for whom buildings on the campus are named — including six residence halls, two classroom buildings, an administrative building and the student bookstore — as having ties to white supremacy. (The details can be found at museum.unc.edu/exhibits/names.)

“If the options were simply to remove the name or to leave it, I would vote in an instant to remove it, for reasons you’ve heard today,” Leloudis said. And, as Muller pointed out, those who approved the Saunders naming in 1922 were two generations beyond Saunders’ acts.

“There’s also no doubt,” Leloudis continued, “that [one of] Saunders’ contemporaries, the eminent historian of North Carolina Joseph Hamilton, who was a defender of the Klan [and for whom Hamilton Hall is named], and the trustees who named this building for Saunders in the 1920s celebrate his influence in that organization, and again I just want to urge us to call the Klan what it was — a terrorist insurgency that used murder and extralegal violence to overthrow democratically elected governments.

“And that’s why I’m drawn to a third option, and that is the option to curate and bring scholarship and bring teaching to bear on Saunders Hall and other contested spaces across our campus. … I think this curation, however it’s configured, is vitally important because we can’t let this historical moment evaporate.”

Chancellor Carol L. Folt and trustees, left to right, Alston Gardner ’77, Charles Duckett ’82, Phillip Clay ’68 and Kelly Hopkins ’95 listened to students and eight invited speakers for two hours in March. Gardner and Duckett led a background study on the renaming issue. (Photo by Travis Long/News & Observer)

In the 10 months since students presented an 800-signature petition calling for the renaming, Gardner and Duckett said they had spent hundreds of hours researching the issue and interviewed about 200 people.

Members of Real Silent Sam declared at a rally in January that Saunders’ name symbolized the continuing second-class status on campus of blacks and other people of color. The coalition also wants UNC to provide information on its racial past at orientation and to attach contextual information to the Confederate war statue erected in McCorkle Place more than a century ago. They have backed off previous demands to have Silent Sam removed.

The coalition is adamant, punctuating their rallies with shouts of “Can you hear us now?” They say they are not asking for Saunders to morph into Hurston Hall — they’re demanding it.

But they have not been characterized by the overt rage of the cafeteria strike in the 1960s or the demands for the black cultural center of the ’80s.

Nearby schools have dealt with renamings recently. Duke University and East Carolina University have decided to remove the name of Charles B. Aycock (class of 1880), whose name is tied to white supremacy, from campus buildings. Carolina also has a dorm named for Aycock.

Clemson University is discussing whether to rename Tillman Hall, a prominent campus landmark at the school’s main entrance. Tillman was South Carolina governor in the Reconstruction era and a leader of the Red Shirts militia, which campaigned to put down the black vote, sometimes violently.

David E. Brown ’75 is senior associate editor of the Review.

The University Affairs Committee’s March 25 meeting is available at bot.unc.edu/agendas.

For two hours, the committee listened to eight invited speakers, who were evenly divided about whether to scrub a 93-year-old classroom building clean of the name of William Saunders. Those who were there found the event captivating. You can watch it in its entirety on the University’s YouTube channel. Read excerpts from some of the speakers.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.