Three on the Tree

Posted on July 26, 2023Two feature stories and a timeline concerning the tulip poplar that witnessed the birth of America’s first public university

stories by Paul Wachter

A Turn for the Better

When winter storms uproot trees and snap power lines, most Chapel Hill residents are, at best, inconvenienced. But for Stephan Moll, a hematologist at UNC’s School of Medicine, the crack of a tree branch spells opportunity. Over the past decade, Moll has become an increasingly skilled and passionate woodturner, collecting wood both locally and afar, and crafting bowls, hollowed-out orbs and other fine objects.

Recently, he was given part of a dying branch cut from the famed Davie Poplar to make a few pieces to raise money for charity and be presented to top donors to the University. But while the Davie is held dear by many UNC alumni, tulip poplars aren’t a particularly prized species by woodturners. They rarely have interesting grain.

UNC hematologist Stephan Moll makes wooden vessels and decorative objects from pieces of the Davie Poplar and other campus trees. (Photo: Carolina Alumni/Cory Dinkel)

Black walnut trees, however, are, Moll said on a recent evening in his backyard garage studio south of Chapel Hill. Moll and some fellow woodturners learned a woman in Selma, North Carolina, planned to cut down a large black walnut on her property. One of her neighbors, who like Moll is a member of the Woodturner’s Guild of North Carolina, volunteered to remove it for her. Moll and two others took their chainsaws to Selma and salvaged the wood, chunks of which rest on his shop floor below shelves supporting several hundred finished and half-finished vessels. Moll identified some other favorite species in the studio — redwood, cypress and Hawaiian koa, that state’s largest native tree, often used for canoes and surfboards.

But for Tar Heels, surely the most prized works on hand were crafted from a branch of the famous Davie Poplar, a tulip poplar named in honor of UNC founder William Richardson Davie, which has stood on McCorkle Place for more than 300 years.

UNC arborist Tom Bythell gave Moll the decaying branch, which Bythell’s team cut down two years ago before it could fall on its own accord, potentially injuring passersby. Moll sells many of his pieces at local craft shows, but he won’t sell the three bowls he made from the Davie because the tree is University property. Instead, the finished pieces will go to retiring University employees and major donors. He uses the proceeds from the sale of some of the pieces he makes to support Door to Door, a program that brings musicians and other entertainers into patients’ rooms and public spaces at UNC hospitals and medical centers. “For patients who are isolated and suffering, they get some whiff of the outside world,” Moll said.

Moll has similar designs for a willow oak that stood on the grounds of the Carolina Inn. It fell in October 2018 during Hurricane Michael, a tropical storm when it reached Chapel Hill, and chunks are stored by the University at its recycling center on Airport Drive. “I’m hoping that the remains can go to local woodturners, who will make pieces and auction them off to raise money for the University,” Moll said.

Moll was born in Germany and has worked at the UNC School of Medicine for 23 years. He’s been woodturning for about 12 years. Photo: Carolina Alumni/Cory Dinkel)

It was a muggy spring evening, but inside Moll’s studio a window air conditioner blasted frigid air. Moll said the chilly conditions had nothing to do with optimal storage conditions for the wood, which is resilient; it’s just his personal preference.

He demonstrated his lathe and showed off various saws and fine-carving instruments — knives, chisels, gouges and veiners, which make deep, U-shaped cuts in wood. He also pointed out a safety mask that he wears when working the lathe, which spins the wood at up to 2,500 revolutions per minute. Not long ago, a large piece of wood split in half while Moll was spinning it on the lathe. A chunk hit his mask, shattering it, and Moll required a few stitches.

The path to UNC

Moll was born in Wuppertal, in what was then West Germany. Both his parents were pediatricians. When he was 5, his family moved to Papenburg, Germany, near the border with Holland.

He graduated from the University of Freiburg Faculty of Medicine in 1986. By then, he had already traveled extensively. As a high school senior, he went to Ogden, Utah, on a student-exchange program. He spent his final year of medical school studying in London.

After graduating, he went on to a residency in pathology in Aachen, Germany, for a couple of years. Then, almost as a lark, he applied to American medical schools for residencies. “I had a friend in Germany who had taken the American residency exam and passed, while bragging about how difficult it was,” Moll said. “So, I took the test just to show him that I could pass, too.”

He did. An avid hiker, Moll applied to schools that were sufficiently close to mountains and settled on Duke University for an internship and residency in internal medicine from 1989 to 1992. He stayed at Duke for another three years and completed a hematology-oncology fellowship. He met his wife, Jackie Vaughan Moll ’88, while she was working as a nurse at the Durham Veterans Administration hospital. They married in 1995 and had their reception at the Carolina Inn.

Moll’s garage workshop is full of half-finished projects and pieces of native and exotic wood in various states of readiness for turning. You can see here why woodturners like to say, “Let’s make some shavings.” (Photo: Carolina Alumni/Cory Dinkel)

The couple wanted to live in Europe and returned to Germany. “We loved Berlin, but I didn’t like the university medical system at all,” Moll said. “It’s very hierarchical — the boss knows it all and needs to make all the decisions. Whereas in America, the chief is more of an administrator, and specialists have more independence.” He accepted an offer from the UNC School of Medicine, where he’s now worked for 23 years.

He compares his field to detective work. “The thing that’s fascinating about hematology is that you’re not focusing on just one organ,” he said. “Hematological diseases can present with neurological symptoms or blood clots. The kidney can be involved. There can be pregnancy complications. As a hematologist, I’m consulted by every other specialty.”

That proved true with the outbreak of COVID-19, which can cause blood clotting in the lungs. “That was the reason patients had to be intubated and many died,” Moll said. “We developed an algorithm to determine how to prevent blood clots with blood thinners, which patients should be given blood thinners and what the proper dosage is.”

The stories behind the wood

In 2011, Moll was flying to a medical conference when he struck up a conversation with his seatmate, an amateur woodturner. Moll was intrigued by the intricacy of the work and reached out to the Woodturner’s Guild of North Carolina, a group of 100 or so hobbyists that hold meetings twice a month.

“Stephan emerged as a real talent,” said Chris Boerner of Angier, who’s been turning for 30 years and previously served as president of the guild. “When he was starting out, I’d give him feedback on proportions and finishes, and we’d collaborate on projects. I’ve bought a couple of pieces from him — his signature wood drops, which are really cool.”

Those pieces resemble drops of blood, though Moll said that wasn’t his intention. “I just like the shape, the look of them, the feel,” he said. But his work has caught the attention of two hematology-focused medical societies — the Anticoagulation Forum and the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis — which have commissioned several of his wood drops.

Moll turned these pieces from Davie Poplar. The Davie’s campus prestige notwithstanding, tulip poplar wood isn’t especially prized by woodturners. (Photo: Carolina Alumni/Cory Dinkel)

Few woodturners can make a living by their craft alone. Pieces by David Ellsworth, a Weaverville-based turner and teacher who founded the American Association of Woodturners, can sell for tens of thousands of dollars. But hobbyists typically get a few hundred dollars for commissioned work or pieces they sell at local art fairs.

“Selling isn’t about the money,” said Durham-based turner Marc Banka, who accompanied Moll on the walnut tree-chopping expedition to Selma. “It’s about the validation and to get rid of these stacks of bowls in my house.” It’s also about getting better at one’s craft, a never-ending education. “I got into woodturning because I didn’t want something I could master in two weeks,” Banka said. “Woodturning is akin to being a musician and handling an instrument. There are always ways to improve.”

Woodturning is not an inexpensive hobby. A lathe and other necessary tools can cost up to $50,000, Moll said. But there are always deals to be had on the secondary market. “Unfortunately, there’s not a lot of demographic diversity in woodturning,” Moll said. “It’s mostly a hobby of retired, white males.” But because woodturners tend to be older, Moll added, “that also means there’s a bunch of good, used equipment around.”

Moll hasn’t pursued much formal woodturning education. He’s taken a few private lessons from Alan Leland, a Durham-based instructor and practitioner, and dutifully attends the guild meetings, which offer demonstrations. “A lot of people watch stuff on YouTube, but I don’t,” he said. “There’s also American Woodturner magazine, but I don’t subscribe to it. I don’t learn as much from reading.” This summer, he hopes to take a course at John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown, in western North Carolina.

Moll has bought wood on only four occasions, and he pointed to a piece of redwood, one of his favorite species, which he had purchased. “It looks bland at first, and it’s surprisingly light,” he said. “But it has a fantastic structure.” Often, it’s the connections from his day job at the hematology division on Manning Drive that lead to interesting material. A friend who’s a nurse practitioner in Visalia, California, gifted him large chunks of an olive tree. On another occasion, a patient sent him three different woods from Hawaii.

Moll’s wood drops look like blood, but he said the resemblance was unintentional. (Photo: Carolina Alumni/Cory Dinkel)

For Moll, the long hours in his studio aren’t the only rewarding part of his craft. It’s also the personal connections he’s forged and an evolving perspective of the natural world. “Woodturning is not just about turning wood, it’s about the whole story behind the wood,” he said.

In an email, Moll wrote he enjoyed meeting the people who live on the properties where the trees he later uses to sculpt pieces had once stood and learning about their history and the tree’s past. He studies the historic uses of various tree species — how, for example, the Phoenicians used cedar for their ships. He was planning a side trip with a guide during an upcoming medical conference in Bangkok to the city’s Wood Street, famous for its various woodcraft merchants. He’s able to notice details about trees that he never would have a decade ago, he said.

“What I’ve found,” Moll said, “is that I walk differently throughout the world now, and I look at trees in a different way.”

Battered But Not Broken

For nearly 200 years, alumni, students and professors have predicted the Davie Poplar’s demise.

The prophecy linking the fate of the Davie to that of the University’s gives one pause, for the campus’s most iconic tree likely has just a few years left, according to University arborist Tom Bythell. (Photo: Mark Terry ’95)

You know the saying: So long as the Davie Poplar stands, the University will thrive, but if the tree falls the school will crumble. The prophecy linking the fate of the Davie to that of the University gives one pause, for the campus’s most iconic tree likely has just a few years left, according to University arborist Tom Bythell. The symbolic tulip poplar on McCorkle Place is widely considered to be more than 300 years old and has long outlived the typical lifespan of its species.

Tulip poplars are lucky to make it to 200 years, which makes the Davie’s longevity remarkable, said Bythell, who has tended UNC’s trees for more than 25 years. In 2020 he received the C. Knox Massey Distinguished Service Award, which recognizes “unusual, meritorious or superior contributions” by University employees. “All bets are off for how much longer Davie will survive,” Bythell said. “No one thought it would be here this long.”

Many of the stories surrounding the tree are apocryphal, including if a couple kisses while sitting on the marble bench at the base of the Davie, they will marry. The most well-known legend has it that William Richardson Davie, the founder of the University, happened upon the tree in 1792 when looking for a site for the new campus. Davie, along with other members of the search committee, rested in the tree’s shade, and according to Archibald Henderson’s 1949 book, The Campus of the First State University, “regaled themselves with exhilarating beverages,” took a nap, and then “unanimously decided that it was useless to search further … no more beautiful or suitable spot could be found.”

In fact, Davie wasn’t among the eight committee members who scouted potential sites, and, on that day at least, there was no boozy respite. Rather, the choice came down to simple economics — Scottish-born James Hogg, a land speculator, organized his North Carolina neighbors, including Christopher Barbee, who enslaved Black people and was the largest landowner in Orange County at the time. Barbee’s holdings included the land that is now McCorkle and Polk places. Hogg and his neighbors offered 1,100 acres of land, $780 and 150,000 bricks for the construction, according to UNC Library’s History on the Hill.

One of the earliest recorded mentions of the tree after the University opened comes in an 1853 letter from William Moseley (class of 1818) to a former professor. “I would like to visit the Old Poplar, in the right of the path leading from the Chapel to Dr. Caldwell’s,” wrote Mosely, who served as an N.C. state legislator and the first governor of Florida. “Is it still alive?” Moseley’s reference lends some support to the purported 300-year-plus age of the tree, which hasn’t been scientifically verified.

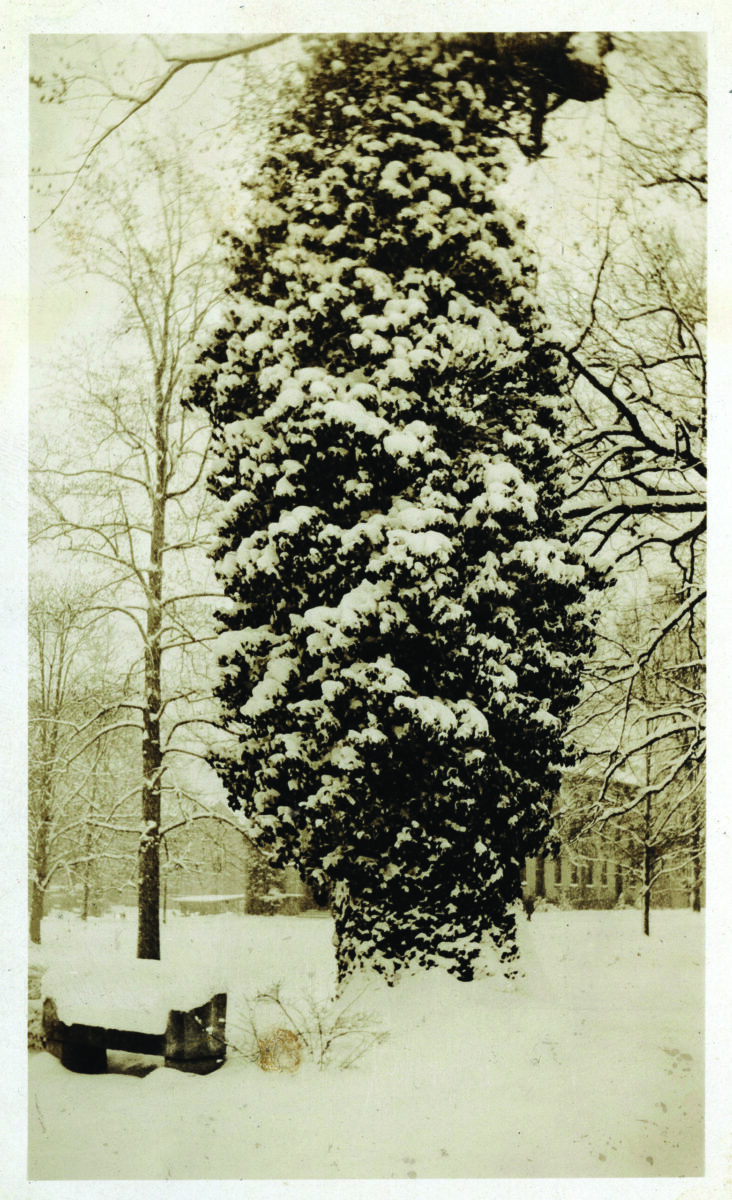

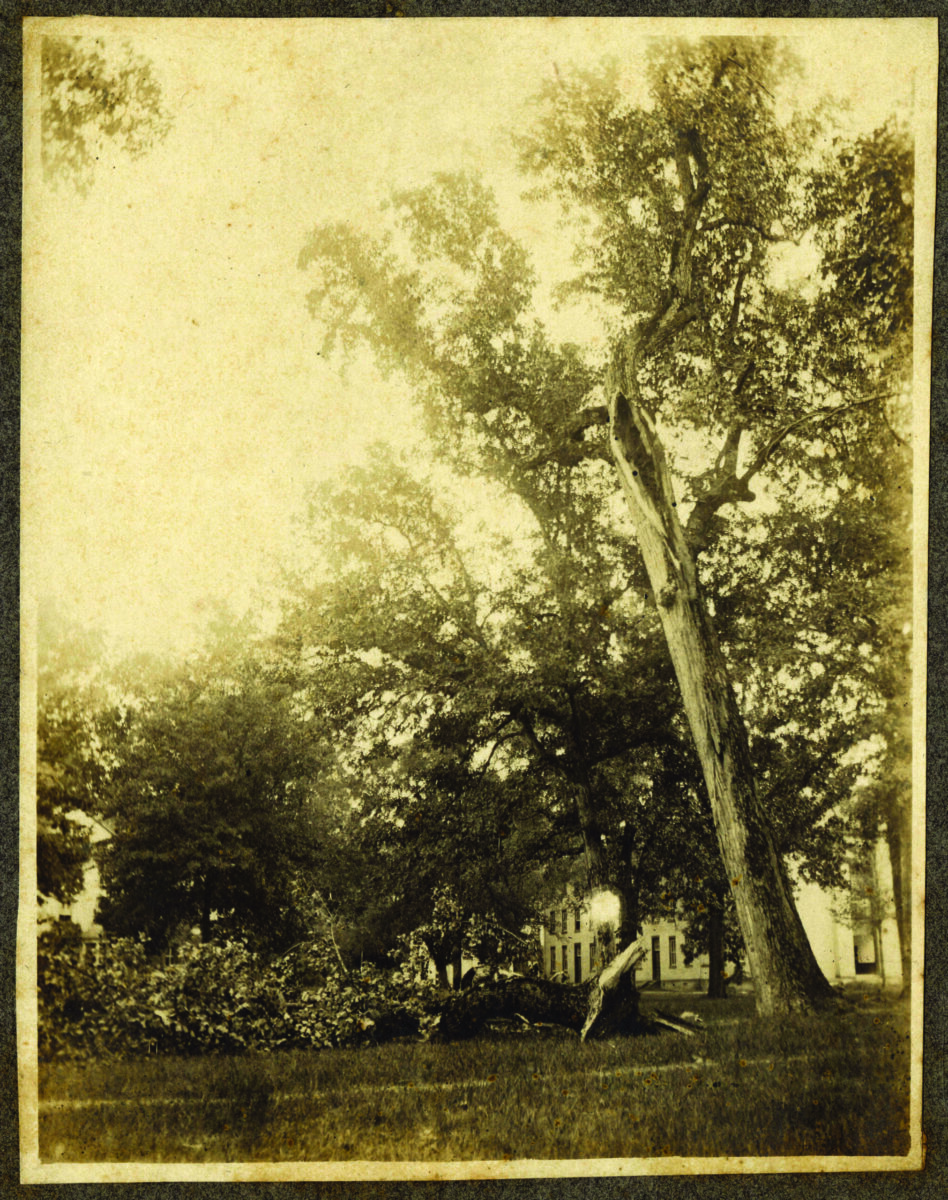

The Davie Poplar circa 1927 (Photo: UNC Library)

Toward the end of the 19th century, the tree became commonly known as the Davie Poplar, a moniker allegedly given by the poet and journalist Cornelia Phillips Spencer.

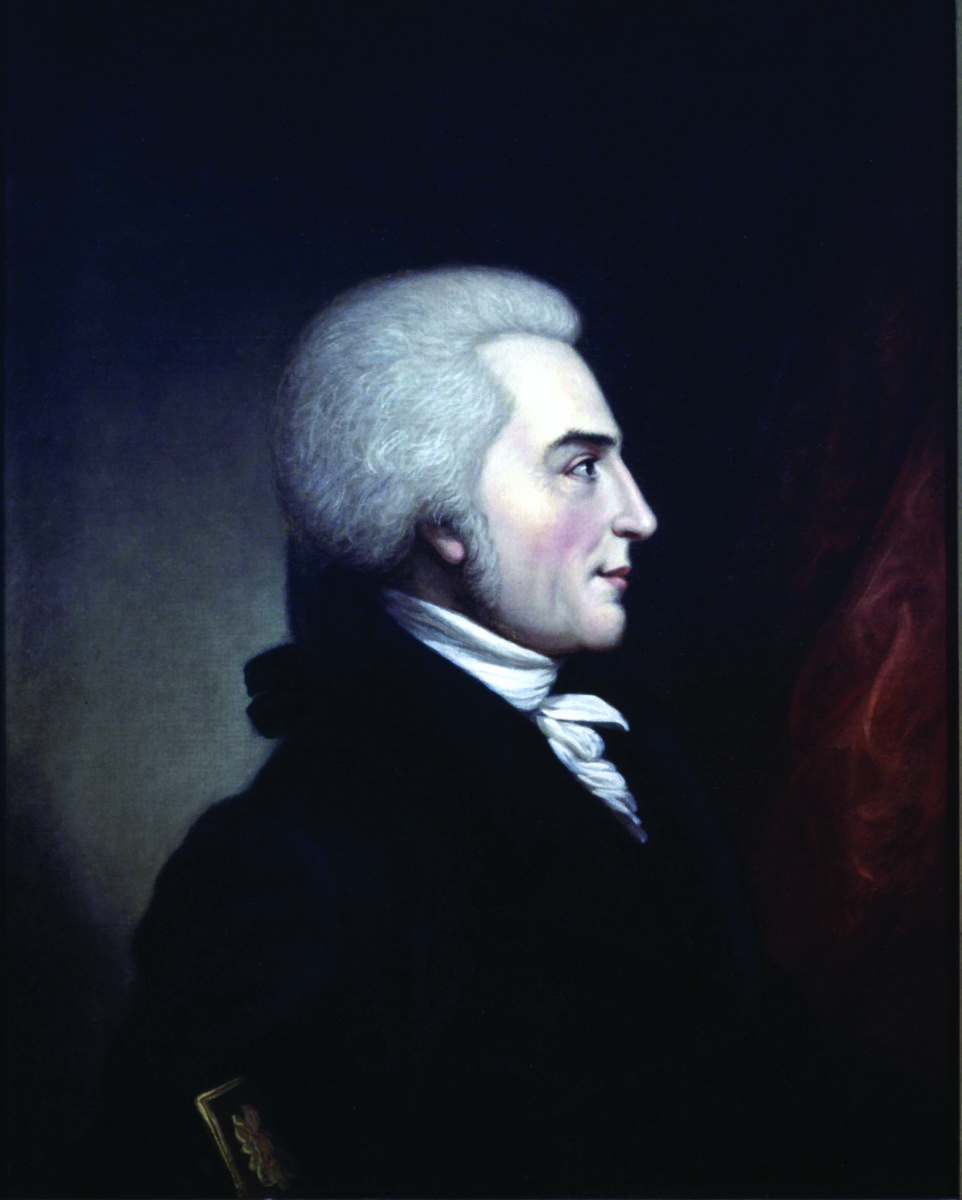

Davie, a lawyer whose Scottish family emigrated from England to South Carolina in the 1760s, “was a gallant cavalry officer in the Revolution,” according to former UNC president and professor Kemp Plummer Battle’s History of the University of North Carolina. Davie served in the N.C. General Assembly, was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia and served as governor from 1798 to 1799 and as minister to France. Davie served on the University’s Board of Trustees from 1789 to 1807 and received UNC’s first honorary degree in 1811. He retired to his South Carolina plantation, home to more than 100 enslaved people. Recent campaigns have aimed to remove Davie’s name from state landmarks; not one has targeted the University.

The Davie Poplar has had outsized significance for generations of UNC students and employees. “The University belongs to all of North Carolina,” Jim Dickens ’51, a former member of the Carolina Alumni Board of Directors told the Carolina Alumni Review in 2013. “And the Davie Poplar is a reminder of that fact.” For some time in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, students would assemble under the tree after Commencement and smoke a “Pipe of Peace,” according to Battle. New graduates would take puffs and then ceremonially hand the pipe to rising seniors.

The tree’s demise has been long-predicted. An article from the April 1918 issue of the Review noted that in 1844 a student, Edmund DeBerry Covington, penned a poem predicting the tree would soon die. In 1997, UNC Botanical Garden director Peter White told the Review that the University “should already be planning for the demise of Davie Poplar” by preparing for a funeral and displaying parts of its “corpse” in a museum.

The tree has had some close calls. In 1873, it was struck by lightning; in 1898, high winds took down two branches; and lightning struck again in 1918. “I’ve seen pictures of the tree after that last lightning strike,” Bythell said. “It looked like a stick, and I’d have guessed it never would have come back.”

In 2017, the grand old tree suffered a burned trunk from a small bomb.

(Photo: UNC/Jon Gardiner ’98)

University administrators also were dubious, which is why they took a graft from the tree and planted Davie Poplar Jr. about 100 feet northeast of the original on March 15, 1918. At the accompanying ceremony, Battle read from Moseley’s letter that referenced “the Old Poplar.” Davie Poplar III was germinated from a seed from the original and planted in front of Alumni Hall in 1993 during the University’s bicentennial. In 1996, Hurricane Fran further damaged the original Davie. In 2017, a young man set off a small, crude bomb at its base, scorching its side.

But perhaps the most persistent threat to the Davie, as well as to the other trees on campus, is soil compaction, Bythell said. “For more than 200 years there have been people walking over the Davie’s footprint, the roots that extend out two-and-a-half times a tree’s height,” he said. “The accumulation of all that impact is harmful for a tree’s health.”

Sometime in the 1950s or 1960s, before Bythell came to UNC from Princeton University, where he was also the head arborist, groundskeepers cabled the Davie to several nearby trees to support the poplar. “But the cables didn’t really accomplish anything,” Bythell said. “In fact, the trees that were connected to the Davie all came down.”

Prior to the cables, groundskeepers in the 1920s considered pouring concrete into the Davie’s hollow trunk. “But a structural engineer from N.C. State advised against it, arguing that shifting the center of gravity likely would bring it down,” Bythell said. Various articles published throughout the years have claimed that concrete was poured inside the Davie, but Bythell is doubtful. “It’s just a rumor,” he said.

Contrary to poplar belief: The Davie is most likely not filled with concrete. (Photo: UNC)

In addition to the prominent Davie relatives on McCorkle Place, there are many others off campus. For the University’s bicentennial in 1993, sixth-grade students from each of the state’s 100 counties were presented saplings from the Davie to plant across the state. English professor Christopher Armitage dressed up as William Davie and rode in on horseback, and men’s basketball coach Dean Smith handed out the saplings. The North Carolina Botanical Garden grew the saplings and several hundred more, giving them to alumni. Whenever the Davie falls, its many descendants will live on.

But just when might it topple? Bythell joked that he’d like the Davie to hang on until his planned retirement in five years. But the likeliest scenario, he said, is that a huge storm will deal the fatal blow. “Fran was a while ago, and it ripped out whole sections of trees,” he said. “Eventually, we’re going to get another big storm with a great downburst and a lot of impact.”

Logical and inevitable as this may seem, the Davie Poplar has, so far, proven wrong the prophets of doom. Recall Edmund Covington, whose 1844 poem said the tree would soon fall. In a strange twist of fate, only a year after his poem was published, Covington died from pneumonia at the tender age of 22.

Timeline of the Davie Poplar

1789

American Revolutionary officer and lawyer, William Richardson Davie, introduces bill in the state legislature to establish a public university in North Carolina.

1792

As several stories tell it, “Father of the University” Davie, and other members of a committee meet under the Davie Poplar on a warm summer day to pick a site for the University. They eat a picnic lunch, regale “themselves with exhilarating beverages provided by hospitable neighbors” and after a nap decide there’s no more beautiful or suitable spot that could be found. The story is most likely not factual. Some reports say Davie wasn’t present.

1818

The Old Poplar was flourishing, according to an 1843 letter written by Gov. William Moseley (class of 1818).

1844

UNC student composes a poem about the Davie in Scottish dialect, predicting the “Auld tottering frien’ ” and “I grieve your course is run.”

1873

Lightning strikes, splitting the Davie’s bark from top to bottom.

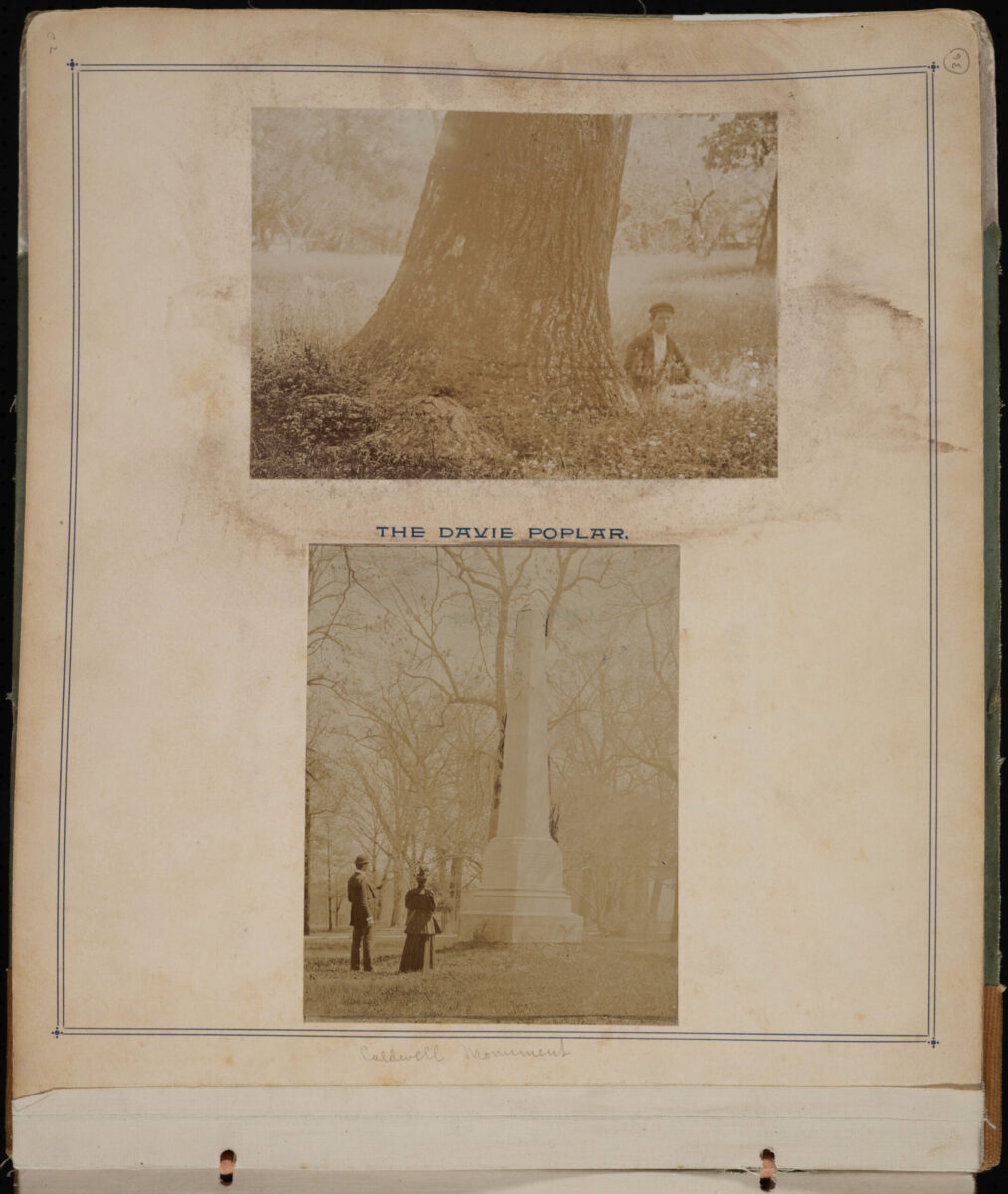

The poplar circa 1892 in a photo album by Kemp Plummer Battle (class of 1849)

1891

Former UNC president and history professor Kemp P. Battle (class of 1849) describes “one of the most interesting occasions of Commencement,” the tradition of recent graduates smoking the pipe of peace under the Old Poplar. “The circle of fine-looking young men, in caps and gowns under the classic tree; the friendly smoking of the ‘Pipe of Peace,’ … ”

1895

Sometime in the late 1800s, Cornelius Phillips Spencer, who was instrumental in reopening the University following reconstruction, gives the tree its current name, the Davie Poplar. The name sticks.

1898

A severe windstorm tears off two large branches.

Davie Poplar circa 1902

1902

Aug. 6, “a fierce wind from the northeast” breaks off two more large limbs. “There was general grief because the symmetry of the Old, or Davie, Poplar was destroyed … and it appeared that the loss was irreparable,” according to the History of the University of North Carolina, Volume II.

1917

Sixty-five members of the graduating class (51 were absent due to entering the federal service for World War I) gather in June under the Davie for last class exercises and “a final whiff of the class pipe,” according to the Alumni Review.

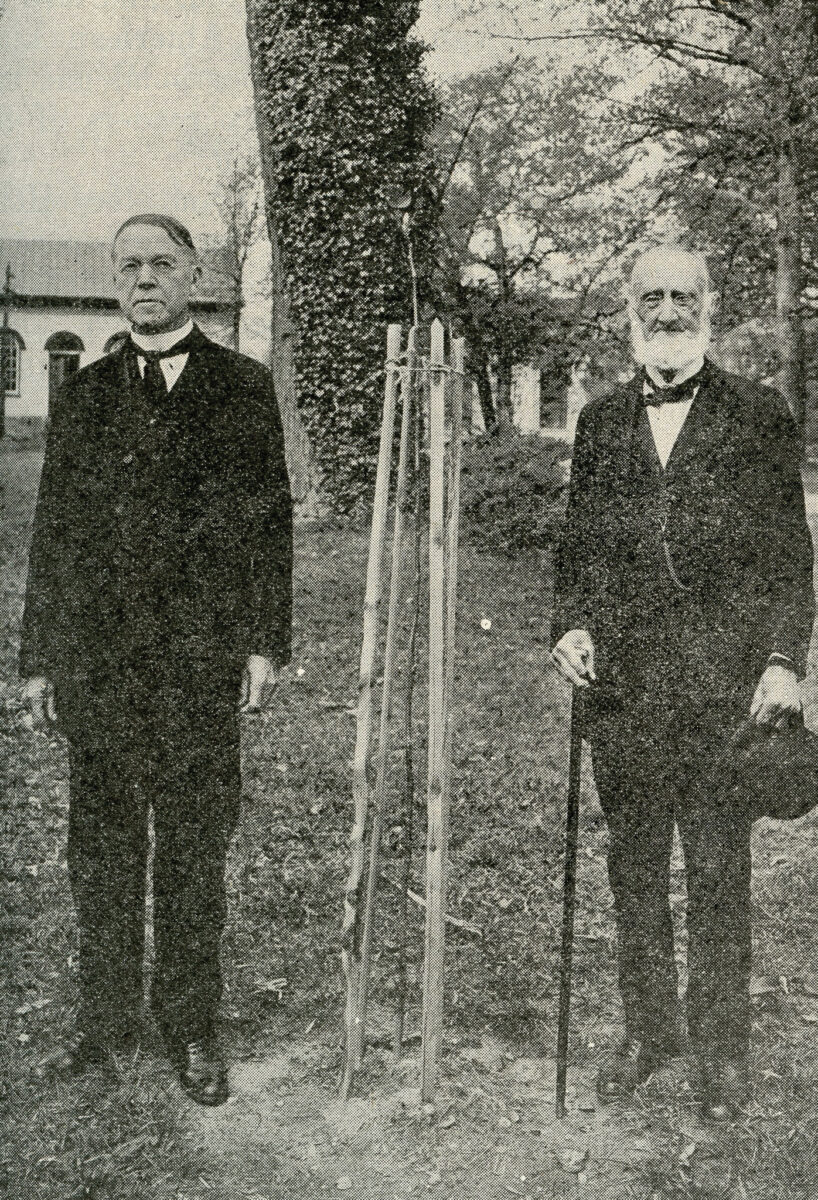

Davie Poplar Jr. planted in 1918.

1918

The Davie is again struck by lightning. March 16, class of 1918 plants Davie Poplar Jr., grafted from a branch of the original, next to its parent.

1925

June 8, class of 1925 holds graduating program under the Davie. That year’s edition of the Yackety Yack yearbook describes the Davie Poplar as “Nature’s Pisa-like commemoration of William R. Davie.”

1944

Large limb falls in storm.

1954

Hurricane Hazel hits Chapel Hill Oct. 15, uprooting a huge oak that held a supporting guy wire connected to the Davie. The tree withstands the storm.

1961

Seven and a half tons of wood trimmed from the Davie. Cables are attached to the Davie and connected to surrounding trees for support. A Fayetteville newspaper editor suggests the “carcass” of the tree be preserved in bronze, like “baby shoes.”

1966

Ice storm damages the Davie.

1963

Class of 1918, which planted a sprig from the original Davie Poplar when they graduated, place a bronze plaque at the foot of Davie Poplar Jr., which was reported at the time as having grown taller than its parent.

1977

Sometime in the late 1970s, an irrigation plan is put into effect and likely saves the tree during the drought of 1986.

1993

During the University’s bicentennial, legendary basketball coach Dean Smith hands out Davie Poplar seedlings from a flat-bed truck to sixth-grade school children from each of North Carolina’s 100 counties.

1996

Davie Poplar withstands Hurricane Fran. Hundreds of trees on campus and surrounding area did not.

2017

A crude bomb at the base of the Davie explodes and burns the tree’s bark. A professor is injured trying to put the fire out.

2023

University Arborist Tom Bethyll says the Davie likely has just a few years left and will likely succumb to a big storm.

Sources: Alumni Review; Carolina Alumni Review; University Report; University Libraries; UNC A to Z; University publications.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.