Tough Choices

Posted on March 2, 2022

Illustration by Haley Hodges ’19

Time’s running out on how UNC will keep its financial promise to low-income students.

by Eric Johnson ’08

In June 2017, then-Chancellor Carol L. Folt took the stage in Chapel Hill for a special announcement. The University had won the Jack Kent Cooke Prize, a million-dollar award that earned Carolina national headlines for its commitment to low-income students.

“The University has given generous financial aid and many additional programs to attract these students and help them graduate,” said Harold O. Levy, a longtime advocate for affordable education and president of the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation. “It provides low-debt, full-need financial aid and admits students on a need-blind basis. Very few colleges do that.”

At Carolina, that exceptionalism has long been touted as a point of pride and an expression of deeper values. “It’s not just something we want to do, it’s really something we must do,” Folt said that day. “It is our responsibility to create access and opportunity and open those doors wide.”

“I think we’re probably good without taking any severe actions for the next few years,” said Rachelle Feldman, who led the Office of Scholarships and Student Aid for the last five years and was promoted to vice provost for enrollment in January. “Beyond that, if we haven’t figured out another source, another model, another fundraising strategy that really works, we’re going to have some tough choices to make.”

—Rachelle Feldman, vice provost for enrollment

Access and opportunity don’t come cheap. In the 2017–18 academic year, just after celebrating the Cooke Prize, the University spent more than $96 million of its own money on grants and scholarships for low- and middle-income students, funding beyond state and federal grants that make up the bulk of financial aid at most colleges. That money bought UNC national recognition, supported a student body where more than 45 percent of undergraduates qualify for need-based aid, and made possible the Carolina Covenant, a celebrated program that allows low-income students to graduate with little or no debt. “It is this University’s deepest commitment,” Folt said.

But by 2020, UNC’s aid spending had fallen by nearly $15 million as policy changes and budget constraints pressured one of Carolina’s signature strengths. As the University pledges to complete its latest fundraising campaign with a drive to collect more scholarship dollars, its commitments to financial aid may be threatened in just a few years.

“I think we’re probably good without taking any severe actions for the next few years,” said Rachelle Feldman, who led the Office of Scholarships and Student Aid for the last five years and was promoted to vice provost for enrollment in January. “Beyond that, if we haven’t figured out another source, another model, another fundraising strategy that really works, we’re going to have some tough choices to make.”

The paradox of flat tuition

For two decades, starting in the 1990s, financial aid at Carolina was supported by setting aside a portion of tuition revenue to cover grants and scholarships for low-income students. UNC’s aid policy covers tuition and fees for needy students, and supports housing, meals, travel and technology expenses.

The tuition set-aside was the linchpin supporting all of Carolina’s aid programs, said Shirley Ort, who oversaw UNC’s aid office from 1997 to 2016. “Being able to meet full need, having the courage to launch the Carolina Covenant — our best-value ranking was really built on that tuition set-aside,” she said.

Even as in-state tuition nearly doubled from 2008 to 2018 , the percentage of low-income and first-generation students on campus increased, and graduation rates improved. UNC was consistently ranked a best-value college by Kiplinger’s and Princeton Review because tuition remained low by national standards and was complemented by generous aid for those who needed it. To this day, most UNC students don’t borrow anything to attend, and debt among those who do is just over $20,000 on average — almost $10,000 below the national norm. “We felt like we had a model that worked,” Ort said.

That began to change in 2014, when the UNC System Board of Governors — determined to halt rising tuition and skeptical about one student’s payments offsetting another student’s costs — capped the amount of need-based aid that UNC could draw from tuition revenue.

And in 2017, the BOG froze resident tuition hikes. UNC’s undergraduate annual tuition rate of $7,019 has been flat since the 2017–18 academic year, and the absence of new revenue has squeezed the financial aid budget. The reduction has been partially offset by more federal funding, but overall support for need-based grants is down by about $12 million — nearly 9 percent — since 2018, even as the portion of needy students held steady. The Office of Scholarships and Student Aid responded by cutting the estimated cost-of-attendance, reducing the average amount awarded for living expenses and increasing the standard amount of loans some students are offered.

“The cap on tuition does reduce the amount of money available for aid, but it also helps keep our education incredibly affordable, so it cuts both ways,” said Nate Knuffman, vice chancellor for finance and operations. “It has certainly put some pressure on our other sources of funding.” The increasing cost of aid comes largely from non-tuition expenses such as housing and dining, which have continued to rise without a defined set-aside to support needy students, Knuffman said.

The University has been looking for aid funding from whatever nontuition sources it can find, leading to year-to-year uncertainty about what level of scholarship support can be sustained. “Every time we have to find other sources that aren’t tuition or private dollars, that’s money that could have gone to something else, so it’s a much harder tradeoff,” Feldman said.

Ort, who retired in 2016, said when she left there was so much pressure to keep UNC’s value rankings that “nobody wanted to be the person who said, ‘We can’t afford to do this next year.’ But there wasn’t a permanent source of support.”

There still isn’t, but Knuffman said that no drastic measures are yet on the table to change UNC’s promise of meeting full need for all admitted students. For years, the University’s aid office has provided a menu of options to reduce spending, from small increases in student borrowing to reducing Carolina Covenant eligibility for out-of-state students. There’s no universal definition for meeting “full need,” so the most obvious way to reduce spending is simply to define “need” in more stringent ways.

Knuffman insisted that any shifts in aid would stay within UNC’s tradition of fair access. “We will protect activities central to Carolina’s mission,” Knuffman said. “Meeting full need is a core value.”

“Once you graduate and you’re not struggling to pay back student loans, you really have the financial and professional freedom to do something meaningful. That’s the true gift of the Covenant.”

—Larry Thi ’13

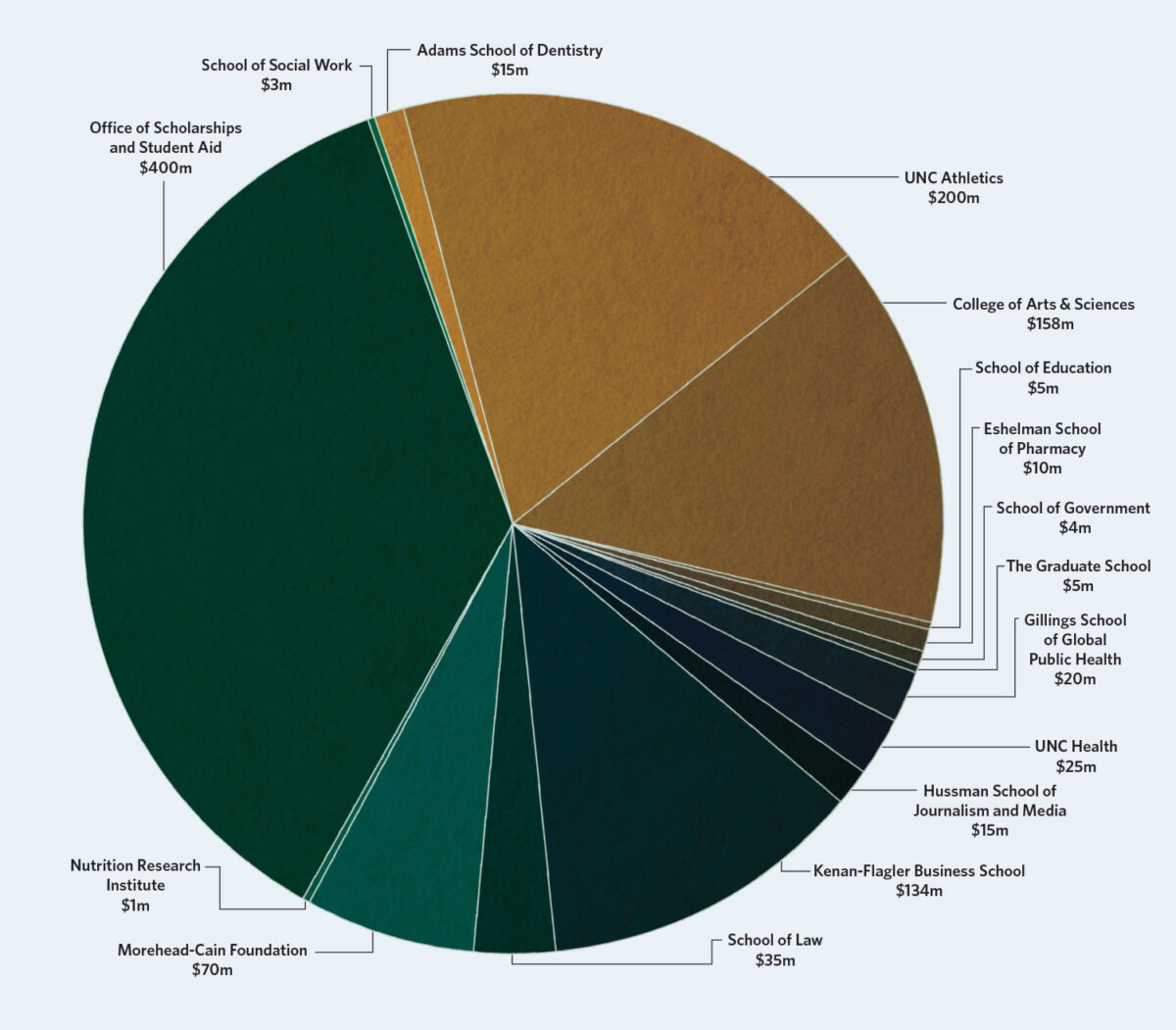

Campaign for Carolina Scholarship Goals: The goals for the 16 schools and units under the Carolina Edge scholarships initiative total about $1 billion. The Office of Scholarships and Student Aid has the biggest goal and has raised half of its target. Source: University Development Office. Data as of Jan. 9, 2022

Aid and competition

Generous aid is also a competitive advantage. In the strange economics of higher education, the best universities in the country aren’t the ones that charge the highest tuition, but the ones that can afford to offer a free or reduced-price education to many of their students.

That’s because need-blind admission — the ability to recruit and enroll the best students you can find, regardless of their ability to pay — is standard practice at highly selective colleges. Schools that promise generous, full-need financial aid are far more competitive than those that depend on every tuition dollar to keep the lights on. Duke, Princeton, the University of Virginia and the University of Michigan have aid policies that are generous to low-income students, much like Carolina’s.

“Generous financial aid is one of the most important things we do to stay competitive,” said Feldman, who directed financial aid at the University of California-Berkeley before coming to Carolina. “It’s key to our remaining a top-tier university.”

Because UNC focuses on serving state residents — 82 percent of its undergraduates are from North Carolina — it enrolls a much needier student body than most of its competitors. North Carolina has a lower median income and a higher poverty rate than the national average, and the University makes an effort to recruit broadly across the state. Twenty-three percent of UNC students are eligible for federal Pell Grants, designated for the lowest-income students and a widely used measure of economic diversity in higher education. At both Duke and the University of Virginia, about 13 percent of students are Pell-eligible.

The fact that UNC reports some of the highest graduation rates nationwide, even with a more economically diverse cohort of students, is a reflection of its aid policies. When the Carolina Covenant program began in 2004, promising a debt-free education for students near the federal poverty line, there was a significant gap in graduation rates between low-income students and their wealthier peers. Since then, as the Covenant expanded from 224 students per class to more than 700 this year, the disparity has nearly disappeared. The program added faculty mentors, internship grants, and an alumni board that helps students build career networks after graduation. “Because they don’t have the worry of how they’ll afford to remain in college, they’re able to engage more in high-impact experiences,” said Candice Powell ’06 (’21 PhD), director of the Carolina Covenant program. “It’s our commitment to being who we say we are, as a public institution.”

Larry Thi ’13 came to Carolina as a transfer student from community college, drawn in part by the University’s promise of meeting full need. “I wanted to go to a place that was academically rigorous and also a place with good financial aid,” Thi said. “Carolina has a really strong history of supporting low-income students and first-generation students, and that really rang true to my experience.”

After graduating, Thi eventually landed a job at the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation — the same organization that awarded UNC the million-dollar prize for its aid programs. He’s now the first chair of the Covenant’s alumni advisory board. “There’s so much good work that needs to get done in the world, and I get to be an asset to my community,” Thi said. “Once you graduate and you’re not struggling to pay back student loans, you really have the financial and professional freedom to do something meaningful. That’s the true gift of the Covenant.”

‘A big, aggressive goal’

The University’s $4.25 billion Campaign for Carolina featured the Covenant prominently as part of a push for more scholarship dollars. With tuition revenue for aid limited, campus leaders have cited donor support as critical for keeping Carolina affordable. “Carolina is one of the last truly public universities,” Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz said in 2019. “We will build upon our commitment to access and affordability.” He pledged to raise a billion dollars in scholarships as part of the capital campaign.

In January, UNC announced the Campaign for Carolina had hit its overall goal of $4.25 billion ahead of schedule. But for the Carolina Edge scholarships, slightly more than $816 million of the $1 billion goal had been raised as of late January. Most of the 16 schools and units in the initiative are on track to meet their individual goals or have already met them. Meanwhile, only half of the $400 million goal for the Office of Scholarships and Student Aid, one of the central pillars of the campaign, had been raised.

“It was a big, aggressive total goal,” said David Routh, vice chancellor for development and the architect of the University’s capital campaign. He also said raising money for scholarships, which are a shared resource across campus, is a challenge because the University’s fundraisers and major donors are typically tied to specific schools or programs. Deans work to keep those dollars within their own domains. There’s less incentive to raise money for scholarships, which are funded through UNC’s central budget and don’t directly benefit a specific school or academic program. (See “What Are You For?”)

Routh said he is optimistic that the University’s fundraisers can “pick up our share of need-based scholarship support” before the campaign draws to a close by the end of the year. “These are really good kids the university wants, and it’s in our best business interest to compete for them.”

Every school and department benefits from financial aid because it supports their students. Figuring out how they should pay to support it is an ongoing discussion for the finance office. “We’ve got some work to do in bridging that disconnect,” Knuffman said.

“In the near future, I think we’re on solid footing. We do have some work to do to ensure that our aid budget is sustainable longer term.”

— Nate Knuffman, vice chancellor for finance and operations

A stopgap, not a solution

The Campaign for Carolina has landed some marquee scholarship gifts. Long-time donors Steve Vetter ’78 and Debbie Vetter ’78 created a $20 million grant program for military-affiliated students, with the GAA contributing another $2 million to that effort through the Lt. Col. Bernard W. Dibbert Scholarship. Former UNC System President Erskine Bowles ’67 gave $5 million to start the Blue Sky Scholars fund for middle-class families.

Some of the largest scholarship gifts of the campaign have been directed at particular subgroups — middle-income students, military-affiliated families — which helps alleviate pressure on the aid budget but doesn’t fully replace the general-purpose funds that make it possible for UNC to meet the full need of all admitted students. And even the most optimistic fundraising scenario wouldn’t bring in enough endowed gifts to fully back the University’s aid commitments.

The amount of the University’s endowment devoted to scholarships and student aid — nearly $420 million as of last October — generates roughly $15 million in expendable funds each year. That’s a sizable contribution, but it doesn’t come close to covering annual costs of more than $80 million.

“Private funding is crucial, but it doesn’t fundamentally change the model of how we’re going to pay for financial aid,” Feldman said.

Carolina can keep its expensive promise to low-income students for now, but there are real challenges ahead. “In the near future, I think we’re on solid footing,” Knuffman said. “We do have some work to do to ensure that our aid budget is sustainable longer term.”

Eric Johnson ’08 is a writer in Chapel Hill. He works for the College Board and the UNC System, and he worked in UNC’s Office of Scholarships and Student Aid from 2013 to 2018.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.