When They Both Were Wanderers

Posted on April 30, 2018

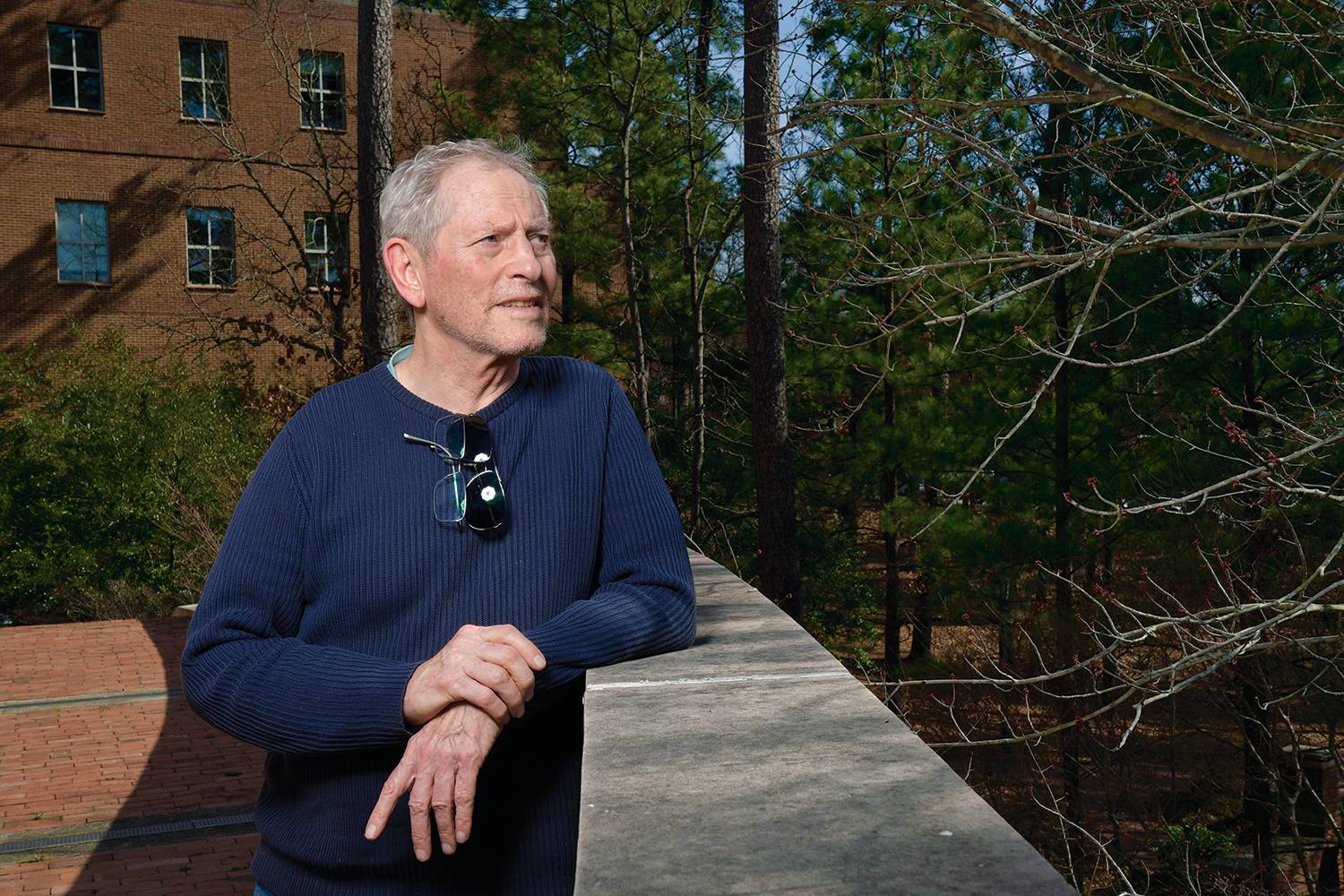

“I didn’t know much about her,” Cary Raditz ’68 said of his initial introduction to Joni Mitchell. “I was not a fan.” (Photo by Grant Halverson ’93)

They made an unlikely pair. Joni Mitchell already had written some of her greatest songs — Both Sides Now, Chelsea Morning, The Circle Game, Big Yellow Taxi. She’d had flings with famous musicians, including Leonard Cohen, David Crosby and Graham Nash.

Cary Raditz ’68 had morphed from a bowtie-wearing Beta Theta Pi to a serious English major, hanging out with an arty crowd and making honor roll. After graduating, he took a copywriting job with an ad agency, but that wasn’t the answer. He soon told his boss, “Life’s too short, I want to travel.”

A charismatic Southerner, as anonymous as the singer was famous, Raditz was destined to have two songs devoted to him on what many consider Mitchell’s greatest album.

In early 1970, feeling smothered by fame and grasping fans, Mitchell sought respite in Europe. She traveled from Athens to a hippie community around the caves of Matala, Crete. Raditz had hitchhiked with a girlfriend from Germany to Matala late the previous year. They settled into one of the numerous caves there, where he made leather sandals to sell. When he returned from a side trip to Afghanistan, his girlfriend was gone, and the cave community was buzzing about a famous singer’s arrival.

“I didn’t know much about her,” Raditz said. “I was not a fan.” To his annoyance, many around him “began acting silly,” mooning over their new celebrity.

By this time, Raditz was a cook, bartender and dishwasher at Delfini’s Cafe, where shepherds drank, danced and smashed glasses by night. He thinks Mitchell may first have seen him being blown out the cafe door when a co-worker lit a cigarette near a faulty propane stove.

Joni Mitchell’s song “Carey” was inspired by her time in Crete spent wth Cary Raditz ’68.

Mitchell, explaining the origin of the song Carey (she misspelled his name) to a 1972 audience, said she entered Delfini’s “and standing behind the counter was this great-looking guy with a great mane of red hair, and a little gold heart in one ear, and a little gold loop in the other ear, and a soiled gray turban on his head.” When she asked where to put her litter, “he took it out of my hands, and with a really ferocious look he threw it all over the floor. … So I liked him immediately, you know, and we became very good friends.”

Raditz says he was surprised to find that Mitchell “wasn’t arrogant or pretentious.” After watching a sunset together, he recalled, “I said, ‘Want to go drinking?’ We went to the Mermaid Cafe,” not far from Delfini’s. “We got really drunk, and she went back to my cave.”

Raditz says Mitchell was seeking refuge from fawners more than she was romance. He was a gruff sort back then, allowing no one in his cave without permission. “It gave her a modicum of privacy,” he says.

She stayed two months, sketching out songs on her dulcimer while Raditz worked at Delfini’s and made sandals. They traveled around Greece, shopped at markets and cooked. “She made me the worst oatmeal I’ve ever had in my life.”

In April 1970, Mitchell invited friends to the cave for Raditz’s 24th birthday. “She sang me this kind of ditty, Carey, on her dulcimer, which I thought was really cute.” He had no inkling that it, and he, would become famous. He’s also the “redneck on a Grecian isle” who “gave me back my smile, but he kept my camera to sell,” according to California, another song on her acclaimed album Blue.

Raditz is also the “redneck on a Grecian isle” who “gave me back my smile, but he kept my camera to sell,” according to Mitchell’s song “California.”

From the start, Mitchell made it clear she wouldn’t stay. (In Carey she sings that “it sure is hard to leave here, Carey, but it’s really not my home.”) Still, Raditz said: “I was really sad to see her go. I was falling in love.”

Mitchell returned to California but sent him a plane ticket to join her. He stayed awhile, meeting Crosby and Nash, who “weren’t very happy about this intruder.”

Raditz returned to Europe, and in November Mitchell invited him to a concert at the London Palladium. There she told him, “I’ve fallen in love with James Taylor.”

“I said, ‘You’ve finally come to your senses.’ ” Raditz had seen Taylor perform at Carolina fraternity parties with his early Chapel Hill bands.

Raditz eventually became a New York-based international banker and spent years working in Africa. He managed his investment strategy practice, taught yoga in Nairobi, married and had three children. He and Mitchell remain friends, he says, and talk now and then. Meanwhile, he’s immortalized in her songs:

Carey, get out your cane. I’ll put on my finest silver. We’ll go to the Mermaid Cafe, have fun tonight. I said, oh, you’re a mean old daddy, but you’re out of sight.

— Charles Babington ’76

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.