A Man of High Office

Few, if any, historians have looked as deeply into the American presidency — and conveyed it with such flair — as Carolina treasure William Leuchtenburg.

by Jack Betts ’68

Bill Leuchtenburg did an odd thing when he was 9 years old. In the habit of keeping his own box scores for baseball games by listening on the radio, he did the same thing for the 1932 Democratic convention, recording the votes from each state for each candidate.

He found the political contestants just as interesting as those on the ball field. “I can remember the candidates were Franklin Roosevelt and Al Smith,” and he goes on to list the eight or 10 more obscure men on the ballot, as if it were yesterday. “I remember the excitement of it, being allowed to stay up late. Then in the morning, I think on the third ballot, Roosevelt coming in the victor.

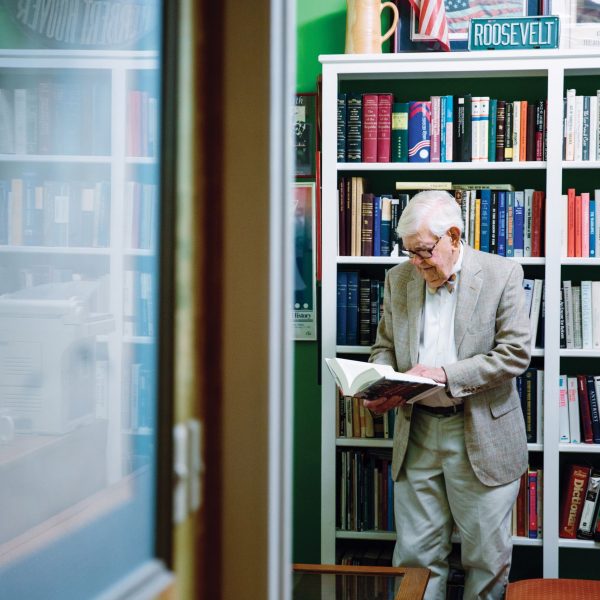

Earlier in his career, Leuchtenburg believed that it was Franklin Roosevelt who so dramatically broadened the powers of the presidency, but more recently he has written that the modern presidency began with FDR’s cousin, Theodore Roosevelt. (Photo by Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

“It seemed perfectly natural to me. We all studied American history. It was part of being a citizen of this country — what it meant to be an American boy. We were taught to revere the presidents of the past.”

During a Depression-era childhood spent poor in rough parts of Manhattan and Queens, the son of parents who didn’t make it to high school, he read whatever he could get his hands on. By the time he was 14, he was a credentialed freelancing sports writer and theater correspondent.

He managed to get three-fourths of what he needed for tuition to start at the school of his choice — Cornell — but the remaining $100 was a mountain to climb. He sold Good Humor ice cream, which was not going well until the day one of the drivers told him Roosevelt was making an appearance in the city.

The budding scholar never found out whether Roosevelt showed up, but he sold enough ice cream bars to the assembled crowd to put him over the top.

As Leuchtenburg studied, he became fascinated with politics and nearly traded in his interest in history. What he did was merge the two, and the result was an activist who marched with Martin Luther King Jr., sued President Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger over protection of historical records, and testified in the U.S. Senate against U.S. Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork. But foremost was his devotion to the events and lessons of the past — author of some of the most highly regarded books on the American presidency, and with his survey of the 20th-century presidents now on bookstore shelves, he has several more in various stages of completion. He’d worked a whole career as an activist historian before he came to Chapel Hill in 1983 to teach and write.

At 94, he has yet to figure out how to slow down.

Leuchtenburg advised documentary historian Ken Burns on Burns’ 1994 series on baseball. The two have worked together on several films, and much of Burns’ archive now resides in Wilson Library. (Photo by Jean Anne Leuchtenburg)

His long collaboration with documentarian Ken Burns continues, on a new film about — of all things — country music. Leuchtenburg advised Burns on his landmark Civil War series and his documentaries on the Roosevelts, the national parks and baseball, among others. (Burns wanted his Civil War archives to reside in the South, and he gave them to Wilson Library.)

Their work together began with the 1986 documentary about Louisiana governor and U.S. Sen. Huey Long. Leuchtenburg had given Burns a copy of his lecture on Long, and thus began a long friendship and working relationship that has thrived, with the elder historian writing memos about odd facts of history and sometimes appearing in the documentaries themselves.

Burns told the Boothbay Register last summer: “We learned a long time ago never to leave home without Bill. If this was a baseball player, Bill would be Willie Mays. He has been an extraordinary addition to our team.”

That’s an image that surely warms the heart of Leuchtenburg, a longtime fan not of Mays’ Giants but of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Still, Mays’ reputation as a player who could do it all with grace and excellence reflects a widely held opinion about Leuchtenburg’s reputation as one of the best ever at what he does.

“For millennia, people have found history indispensable to comprehending who they are,” Leuchtenburg has written. He frequently cites a saying of the Lakota tribe: “A people without history is like the wind upon the buffalo grass.”

Statesmen and scalawags

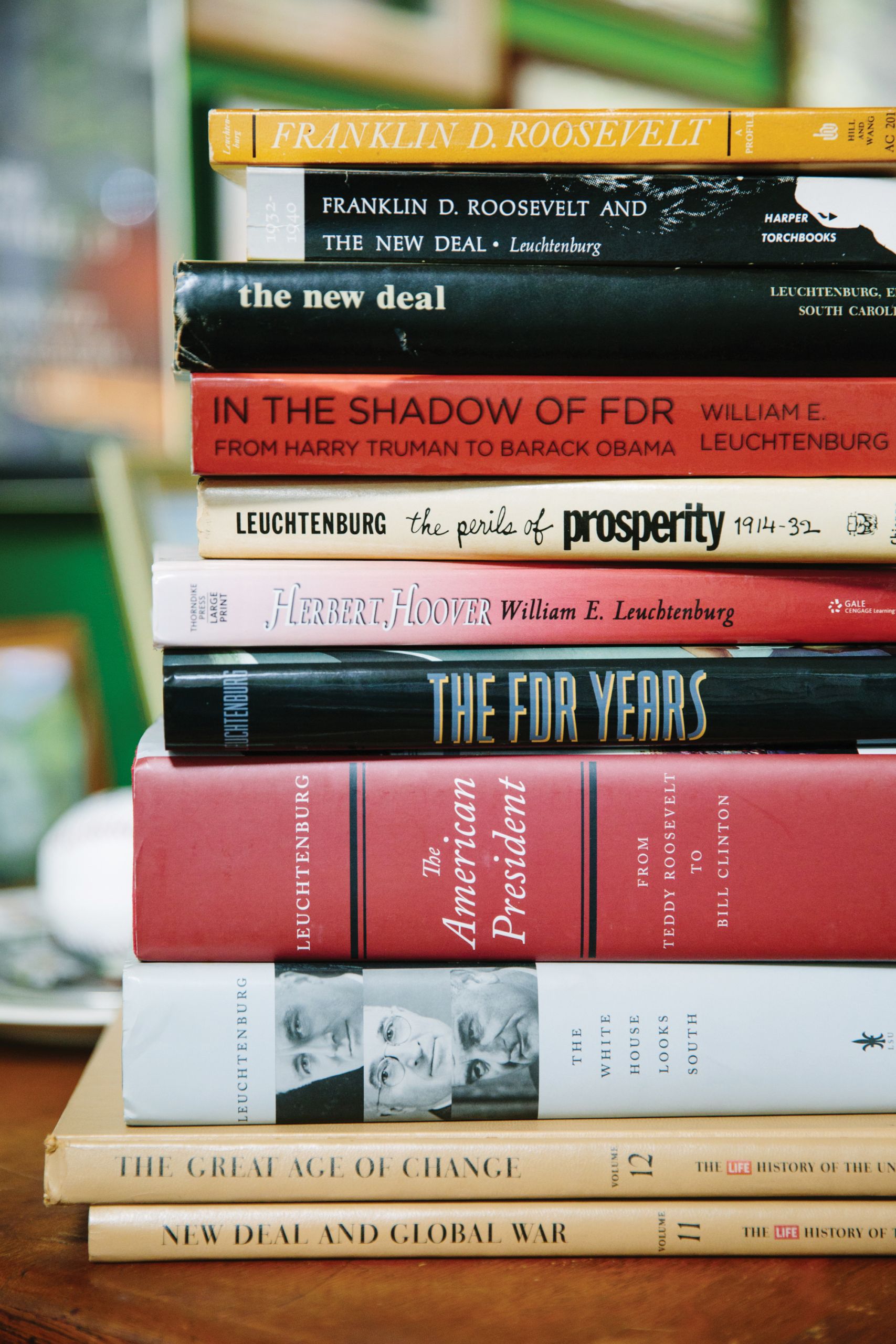

Leuchtenburg is the author of more than a dozen books on 20th-century American history. (Photo by Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

Leuchtenburg’s most recent book, The American President: From Teddy Roosevelt to Bill Clinton, published by Oxford Press a year ago, is an 812-page account of each of the presidents’ contributions to the presidency since early in the 20th century. It is packed with vivid writing, illuminated by the pithy quote, the telling anecdote and the sharply drawn point that represents high-caliber storytelling, whether journalistic, historic or in the oral tradition.

Leuchtenburg wrote that Ronald Reagan, a masterful communicator who struck a warm chord with many Americans, often had higher regard for a good story than for the facts.

“Remarkably, he found it hard to fathom why truth should be privileged over make-believe. [Reagan] spun one narrative after another that was palpably untrue. In 1985, he recalled his horror at his first encounter with Nazi death camps as a Signal Corps photographer in Europe during World War II, though he had never left the United States at any time during the war. More than once, he told the story of a heroic wartime pilot who, instead of bailing out and leaving a wounded crewman to his fate, said, ‘Never mind, son, we’ll ride it down together.’ Even when it was pointed out to him that there was no way to know what one man said to another as they plunged to their deaths, he would not be dissuaded. Reagan’s tale, it turned out, derived from the movie A Wing and a Prayer, starring Dana Andrews.”

Leuchtenburg presents an acerbic view of Bill and Hillary Clinton. For all his charm and ability to communicate, Bill Clinton, he wrote, as president often was unfocused and undisciplined, more noted for proposed initiatives than for accomplishments, few legislative achievements of any historical importance, a record riddled with missed opportunities and forever tainted by his dalliances with women. Clinton’s position in the country’s annals is secure not because of all he sought to do and did, Leuchtenburg wrote, but because he is the first elected president in the more than 100 years of the American republic to have been impeached.

Clinton, he wrote, had studied FDR’s record and hoped one day to be as well regarded. Time turned that into an elusive goal, and even his successes failed to put him in the upper tier of presidents. In his final year in office, Clinton had high hopes for a reconciliation accord in the Middle East.

“Two days after the House Judiciary Committee voted to impeach him, the president turned up in Gaza to hear the Palestinian National Council carry out its pledge to repudiate articles in its Covenant calling for abolition of the State of Israel. In subsequent negotiations during his final year in office, Clinton appeared to be making progress, but at a critical moment, [Yasser] Arafat balked. ‘You are a great man and a great president,’ Arafat told him as his days in the White House were drawing to a close. ‘The hell I am,’ Clinton replied. ‘I’m a colossal failure, and you made me one.’ ”

Nor is Hillary Clinton spared for her role in developing a national health care bill. From the outset, she had a West Wing office, a veto over major appointments and — for saving her husband from one sex scandal and preserving their marriage — an understanding that she would drive the health care proposal almost as a quid pro quo, according to one historian. She was indifferent or insensitive to how her determination to forge ahead was affecting prospects for passage of the bill, ignored the need to keep congressional leaders in the loop, and displayed an arrogance that seemed to drive away even potential Democratic votes, Leuchtenburg wrote.

Leuchtenburg in his writer’s cottage in Chapel Hill. His current projects include research on the presidency in the 19th century, which he may divide into more than one book. (Photo by Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

The book stops with the Clinton presidency in January 2001 and Leuchtenburg’s biting description of the U.S. Supreme Court’s stepping into the 2000 election to, in effect, award the presidency to George W. Bush. A month after Election Day in 2000, the court ruled 5-4 that the Florida Supreme Court had violated the equal protection clause, a decision that decided the election for Bush over Al Gore, who — as Americans were reminded following 2016’s election — had won the popular vote but not the Electoral College.

Leuchtenburg wrote that the decision seemed blatantly biased and untethered in doctrine. Each of the justices voting in Bush’s favor had been appointed by Republicans, and nothing in their past opinions squared with their reasoning in this case.

But it also was important to remember Bill Clinton’s impact on that electoral outcome: Forty-four percent of the electorate, exit polls revealed, said that Clinton scandals were important in determining their vote; not surprisingly, those who reported that uneasiness went overwhelmingly for Bush, he noted.

Earlier in his career, Leuchtenburg believed that it was Franklin Roosevelt who so dramatically broadened the powers of the presidency, but more recently he has written that the modern presidency began with FDR’s cousin, Theodore Roosevelt.

After William McKinley was assassinated in 1901, the prospect of his vice president moving into the White House horrified some people. Industrialist Mark Hanna told a journalist on the funeral train that he had advised McKinley that it was “a mistake to nominate that wild man at Philadelphia. … Now look, that damned cowboy is president of the United States.”

But few enjoyed the office as much as Teddy Roosevelt, and the public came to appreciate his attentiveness to the country’s assets.

When Congress showed no interest in preserving habitat, he acted on his own to create America’s first bird refuge — at Pelican Island in Florida. Before he was done, he added 50 more. He explained: “To lose the chance to see frigate-birds soaring in circles above the storm, or a file of pelicans winging their way homeward across the crimson afterglow of the sunset, or … myriad terns flashing in the bright light of midday as they hover in a shifting maze above the beach — why, the loss is like the loss of a gallery of masterpieces of the artists of old time.”

Our presidents, Leuchtenburg wrote in the concluding pages, have shaped the country we live in, given us reason for pride, made courageous stands during times of difficulty and sorrow. “Yet the dark underside of presidential power cannot be ignored. Too often, presidents have lied to us. Too often, they have wasted the lives of our children in foreign ventures that should never have been undertaken. They are both the progenitors and the victims of inflated expectations, and when they over-reach, they need to be checked.”

Leuchtenburg is shown with historians John Hope Franklin, John Higham and Arthur Mann at the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery march. (Photo copyright by Dennis Hopper, courtesy of the Hopper Art Trust)

Leuchtenburg, pictured above with President Lyndon Johnson in 1965, had access to the Johnson White House while he worked on a campaign against the Vietnam War. (Photo courtesy of Bill Leuchtenburg)

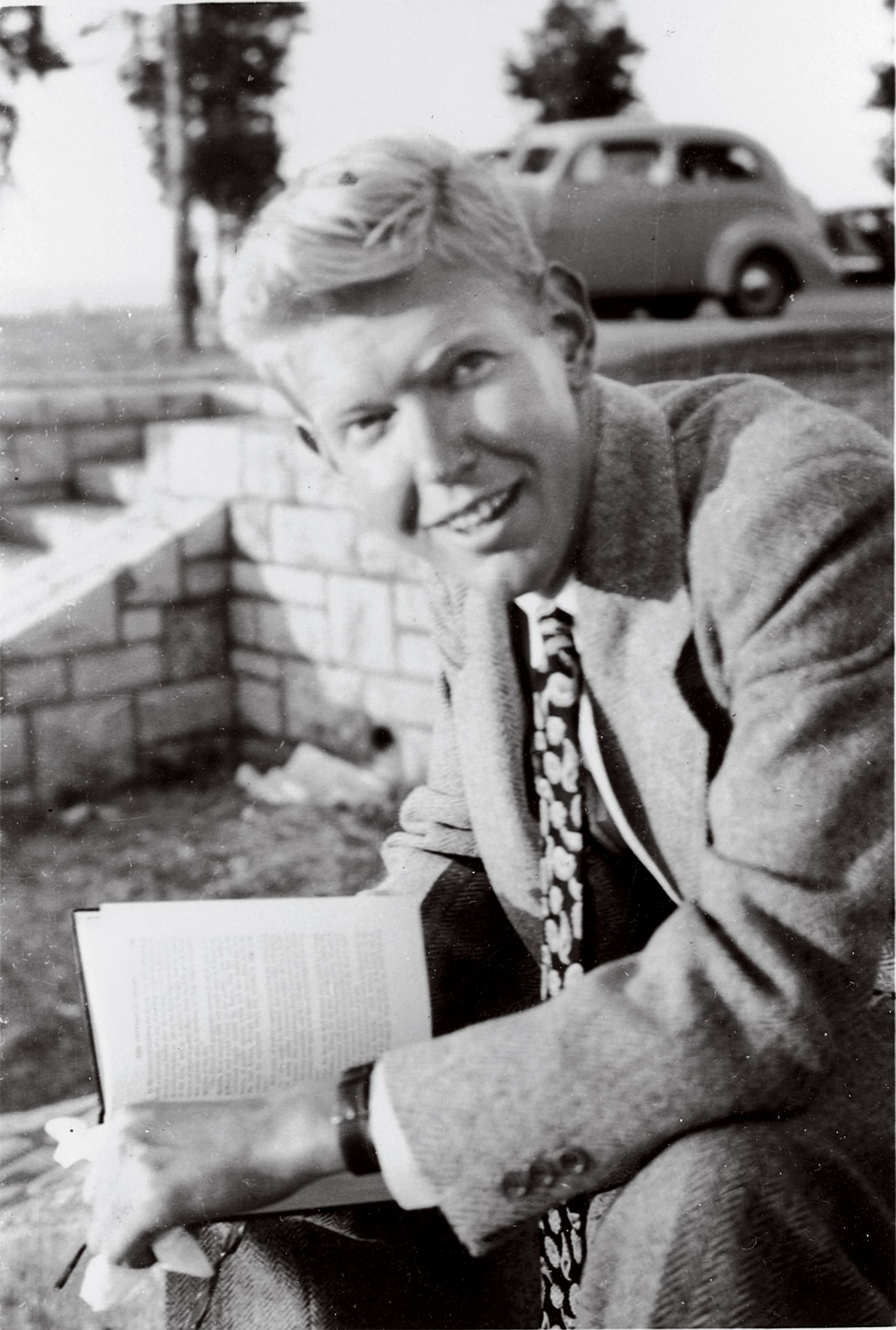

Leuchtenburg in Kansas City, Mo., in 1948 as he was managing Richard Bolling’s first campaign for Congress during a hiatus from academics. He also spent part of this time working on the field staff of a civil rights organization in Maine. (Photo courtesy of Bill Leuchtenburg)

Beyond the mere observer

Years ago, Leuchtenburg’s then-teenage stepson reminded him of the old joke that goes, “Of course, you were good in history, Dad — you were there for most of it.”

While researching and chronicling history and teaching — he lectured at Columbia for three decades before accepting UNC’s William Rand Kenan Jr. chair in history — he helped network news anchors analyze election results and post-election climates, and he supervised recollections of John Kennedy after his assassination, among other high-profile assignments. He gave Carolina nine years before retiring very gradually, and still he is sought by politicians and journalists for his expertise and by alumni groups for his talks, nearly peerless among scholars of FDR.

From the beginning of his career, he has been not a mere observer but a hands-on historian who in time would combine his scholarly research, keen analytical skills, considerable grace in both the spoken and written word, and an overriding sense of fairness with the practical experience of the grass-roots field operative. It gave him a solid background about what really happens in government and in politics and public affairs, an advantage that would inform and enliven his writings for decades to come.

In 1992, he told the Review a story of what pulled him back from veering full-bore into politics. He’d been working with Americans for Democratic Action’s effort to draft Dwight Eisenhower, then fresh out of World War II, for president — on the Democratic ticket.

“After it was all over, I said to myself, ‘Now that was an awfully silly thing to be involved in,’ ” he told the Review. “I need a little time off to think through exactly what it is that I’m doing. I realized that we knew very little about Eisenhower and, in fact, Eisenhower turned out to be a fairly conservative man, a Republican. The whole attempt was quixotic.”

Leuchtenburg was, and is, decidedly on the other end of the spectrum. A devotee of the New Deal, he already was one of the foremost FDR scholars when he left Columbia.

It’s no secret that he leans to the left, but anyone reading his books quickly realizes that he spares no one in his analyses — not FDR, not Harry Truman, not Kennedy and certainly not the Clintons. He recognizes their successes but takes pointed note of their failures of action and their inability to act effectively when presented with opportunity and demand.

He also is careful to avoid a trap that some historians encounter — the specious belief that the past will show how to solve future problems. He believes historians have a role to play — a role as truth tellers who deal in facts, which may help public officials better understand challenges.

“My conviction that historians have something to contribute to decision making rests primarily … on a much more fundamental proposition: that movers and shakers act in part because of the history they carry around in their heads,” he wrote more than 25 years ago in an address to the American Historical Association.

That version of history, incomplete at best, often is simply wrong. “Those of us who do take part in public affairs need constantly to remind ourselves that we are not omniscient and that we must never, no matter how worthy the cause, compromise our commitment to, in [historian] John Higham’s words, ‘the simple axiom that history is basically an effort to tell the truth about the past.’ ”

Jack Betts ’68 of Meadows of Dan, Va., is a former associate editor of The Charlotte Observer and a past member of the GAA Board of Directors.

Leuchtenburg dislikes being asked to make predictions, but he does not shy from what he sees as the truth. Two days after the 2016 general election, the Review asked him what he took away from the campaign. Read the Q&A.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.