Back from the Abyss

Posted on April 29, 2024Rwenshaun Miller ’09 battled back from mental illness and the brink of suicide. Now he brings his own culture to help others like him — while convincing Black communities it isn’t taboo to seek treatment.

by Laurie D. Willis ’86

WARNING: This article deals with suffering from depression and anxiety, alcohol addiction and suicide. Details may be upsetting to some readers.

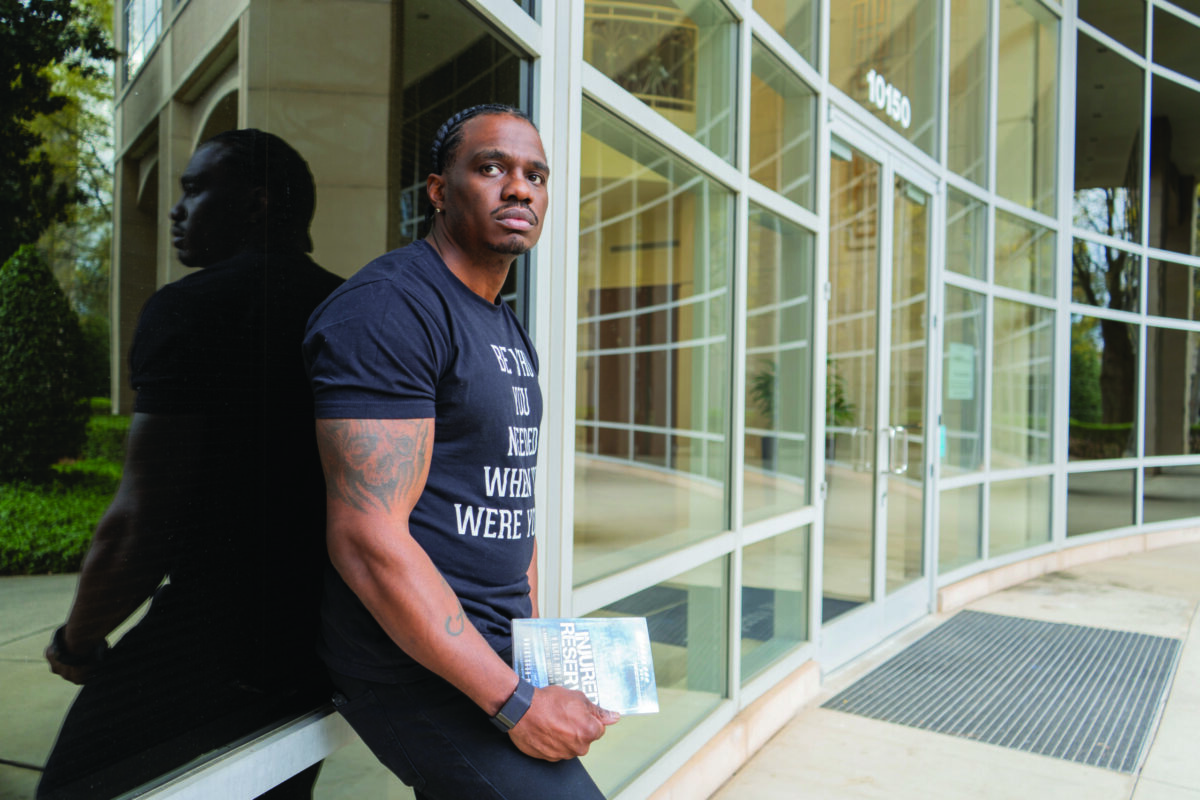

In a daily journal, Miller keeps track of his interactions, how he spends his leisure time, his feelings and what he consumes. (Photo: Robert Singh)

His mind had to be playing tricks on him, he thought, sitting in his Morrison South dorm room. Surely he wasn’t really hearing voices in his head.

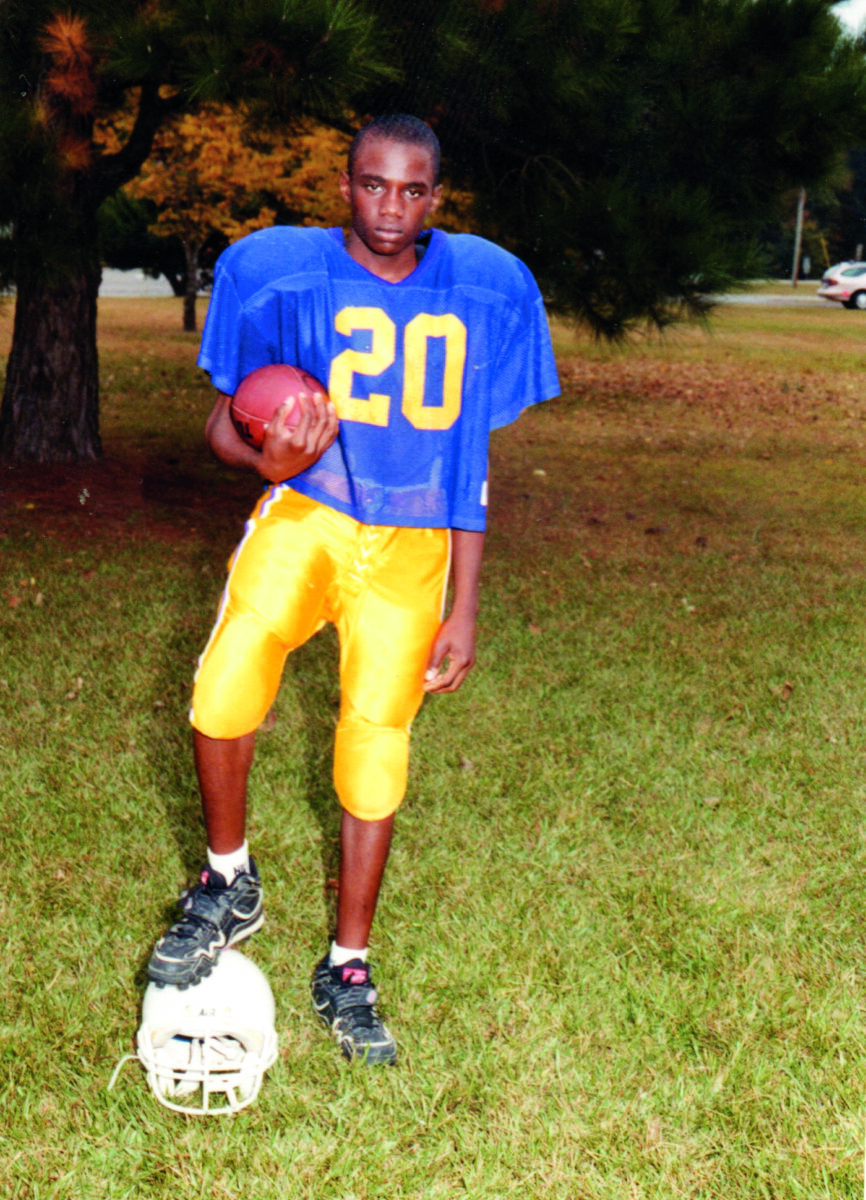

Not Rwenshaun Miller ’09, a hometown hero in Lewiston Woodville in Eastern North Carolina, a member of the National Honor Society and a star athlete in three sports at Bertie High School, where he was sixth in his graduating class.

He couldn’t be hearing voices, Miller told himself, because only crazy people hear things that aren’t there. Besides, he thought, he was a sophomore at UNC, one of the best universities in the country.

It was 2006, a time when people didn’t openly discuss mental illness, especially in the Black community where acknowledging it was taboo. So the last thing Miller wanted to do was admit he was mentally ill. Yet, like thousands of U.S. college students, he was.

The voices

“When you’re arguing with someone, and you don’t agree with them, you can just walk away. But you can’t walk away from voices in your head.” —Rwenshaun Miller ’09

Mental illness among college students nationwide has been on the rise, according to a University of Michigan study released last year that found the rates of college students reporting anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts reached the highest recorded levels in the 15 years the school has been conducting its Healthy Minds Study. About the same time Michigan released its results, Gov. Roy Cooper ’79 (’82 JD) announced $7.7 million in funding to provide additional mental health services to students at the state’s postsecondary institutions. Cooper said identifying college students’ mental distress and providing them access to treatment was more critical than ever.

The UNC System has used the money, in part, to establish an after-hours mental health hotline and training programs for suicide prevention for faculty, staff and students. Annually, the UNC System partners with independent colleges and the N.C. Community College System to host a meeting of hundreds of student affairs professionals and mental health experts to share best practices and discuss improvements to behavioral health. Another conference will be held this year.

Colleges are paying more attention to mental illness, most likely because of shootings on campus and an increase in the rate of mental illness and suicides among students.

But in 2005, when Miller’s parents dropped him off for his freshman year at UNC, students’ mental health awareness among university administrators or lawmakers nationwide had yet to command attention. Miller also wasn’t focused on it. After all, he had excelled academically and had earned a scholarship to UNC. He was a successful athlete, having earned Athlete of the Year honors his senior year in high school, Academic Athlete of the Year two years in a row, All-State and All-Region honors in the 400 meter dash and All-Conference honors in football.

When Miller was in middle school, his mother paid him $10 for every A and $5 for every B he earned on his report card. “He was breaking me,” Myra Miller said, laughing. “But he would have done well even if I wasn’t paying him.”

Miller went from being a standout athlete at a small, predominantly Black high school, to a walk-on with the football and track teams at the much larger, predominantly white UNC. “My ego took a hit as well as my identity,” he said. “Growing up, I was always considered the smart kid, a great athlete, but I got to Carolina and realized there were a lot of people there like that.”

But life at UNC was much different than what Miller experienced in Lewiston Woodville. He went from being a standout athlete at Bertie High School, a small, predominantly Black school in the neighboring town of Windsor, to a walk-on with the football and track teams at the much larger, predominantly white UNC. “My ego took a hit as well as my identity,” Miller said. “Growing up, I was always considered the smart kid, a great athlete, but I got to Carolina and realized there were a lot of people there like that.”

Miller enrolled at Carolina with aspirations of becoming a doctor, primarily because people back home thought he should. But in his first semester, his grades in his premed classes were low, and he was put on academic probation. Miller lost his academic scholarship but didn’t disclose that, or his newly acquired student loans, to his parents.

In his second semester, Miller switched his major from biology to sociology, and his grades improved. He was removed from academic probation in the fall of his sophomore year. But then more heartache: He tore his ACL in his right knee. No more football. No more track.

Miller began having trouble sleeping, and his thoughts raced. Outside of class, Miller avoided people and lied to his mother about how he was doing, feeling ashamed. Then one day later that semester, in his dorm room, Miller heard three distinct male voices in his head telling him he was worthless and no one would care if he died. Miller said he was scared and confused and thought he was going crazy. But he didn’t dare tell anyone because he couldn’t bear the thought of actually being called crazy.

“A mother knows”

Miller’s reactions are common among people with mental illness because of a long-standing stigma around it, but society is slowly becoming more accepting, said Dr. Samantha Meltzer-Brody ’03 (MPH), chair of UNC’s department of psychiatry. “There is much more openness now to discussing mental health concerns, and many people very openly share their experiences on social media and other public forums, which I believe helps others feel comfortable to ask for help,” she said.

Former UNC basketball standout Leaky Black ’22 shared in a 2022 New York Times article that he suffers from anxiety, and NBA stars Kevin Love and DeMar DeRozan have spoken openly about suffering from anxiety and depression.

But Miller kept silent about what he was experiencing. He also stopped attending classes regularly. “When you’re arguing with someone, and you don’t agree with them, you can just walk away. But you can’t walk away from voices in your head,” he said.

Miller said he now realizes he should have sought help much sooner than he did.

The voices became unbearable. Miller stopped bathing and combing his hair. Eventually, his mother suspected something was wrong. “I could hear it in his voice,” Myra Miller said. “It sounded like he was depressed. He kept saying, ‘I’m fine. I’m fine,’ but I could tell he wasn’t telling me the truth. A mother knows her child, and you can tell when something’s wrong.”

One night in fall 2006, Miller called his parents and told them someone was telling him to kill himself. Myra pleaded with her son not to harm himself. She called her niece, Joyvita Dameron, then a student at N.C. Central University, to ask her to drive to Chapel Hill and bring Rwenshaun back to Dameron’s apartment in Durham. After Myra hung up, she and her sister and brother-in-law got into the car to drive the nearly three hours to Durham.

Meanwhile, Dameron knocked on Miller’s apartment door, but he wouldn’t answer. His roommate let her in, and when she entered, she saw a shell of the man she considered a brother more than a first cousin and began crying.

The short, somber ride to Durham seemed much longer than it was. “She kept asking me what was wrong, but I wouldn’t talk,” Miller recalled. “As she was talking to me, I’m still hearing voices, and I was trying to figure out what was going on. I knew I was going crazy, for lack of a better word, but I didn’t want to admit it. It’s taboo in our community. If I vocalize it, then it becomes real.”

When Miller’s mother, aunt and uncle arrived at Dameron’s apartment, they were shocked by his appearance. He’d lost 25 pounds, smelled because he hadn’t been bathing and his hair was a mess. He refused to talk to them but agreed to go for a ride. When he realized they were taking him to a hospital, he became belligerent.

They arrived at Duke University Medical Center, where Miller inadvertently struck a nurse as employees tried to restrain him. He was sedated and placed in a straitjacket. After a few days, he started talking to the doctors, who eventually diagnosed him with bipolar I disorder with psychotic features.

People with bipolar I disorder have bouts of depression, sometimes followed by periods of severe highs and severe lows, which can precede breaks from reality. Individuals diagnosed as bipolar are advised to remove stressors from their lives. For Miller, attending college was stressful.

Miller’s mother was with him when he received the diagnosis. The doctor said Rwenshaun needed to begin therapy, start taking an anti-psychotic drug and a mood stabilizer and take a break from school. Miller took a medical withdrawal from UNC and moved to Charlotte to live temporarily with his uncle, who operated group homes throughout North Carolina for adolescents with behavioral issues. Miller was happy living with his uncle because he wanted to avoid returning home where he would most likely face questions about why he wasn’t in Chapel Hill.

Emotionally and mentally exhausted

But Miller didn’t take his prescribed medicine, and soon the voices returned. Miller’s uncle connected him with Kendell Jasper, an African American clinical psychologist whose laidback counseling approach — Jasper wore a T-shirt and basketball shorts at their first appointment — comforted Miller.

Miller, who said he had developed a distrust of most white doctors, felt at ease with Jasper. When he was young, Miller had heard stories about the Tuskegee Experiment, a 40-year federal government study that examined the effects of syphilis in Black men, who were never informed of their diagnosis or offered treatment that was developed a few years later. Many died. Miller said he could relate to Jasper and believed the therapist cared about his well-being. “His approach was completely different from what I saw in the hospital,” he said. “I talked to him right away. He made me feel comfortable, like I could trust him out the gate.”

Miller said Jasper helped him understand his diagnosis and told him, unequivocally, he had to take his meds regularly if he wanted to get better. Jasper wasn’t licensed to prescribe medicine, so he referred Miller to a doctor who could write prescriptions but was white.

Miller protested seeing the white doctor, so Jasper went with him to his first session, where he was prescribed medication. Miller continued to see Jasper weekly.

When Jasper thought Miller was ready, he submitted documentation to UNC affirming Miller had the mental capacity to return to school and was no longer a threat to himself or anyone else. Miller reapplied and was accepted, but he couldn’t return to campus until a UNC doctor assessed him and signed off on his readmission.

A 2022 survey of more than 54,000 undergraduates by the American College Health Association revealed

-

35% of students had been diagnosed with anxiety.

-

27% of students had been diagnosed with depression or another mood disorder.

-

8% had been diagnosed with a trauma or stress-related disorder,

-

3% had been diagnosed with bipolar I, bipolar II or a hypomanic episode.

Once back on campus, Miller was feeling better, and the voices inside his head were growing ever fainter. He thought he was cured. “I realize now I was just in denial, not accepting the fact that bipolar disorder was something I was going to have to live with for the rest of my life,” he said.

Before long, Miller again stopped taking his meds because he said they made him feel sluggish, and he wanted to feel normal. He stopped his sessions with Jasper. The voices quickly returned. Instead of resuming his prescription drugs, Miller started self-medicating with alcohol, drinking about a fifth of Patrón Tequila every two days. In class, he would drink the alcohol from a water bottle.

One night, he was so emotionally and mentally exhausted, Miller decided to take an overdose of his meds and went to bed, expecting not to wake up. But he woke up the next morning, and he remembers being disappointed because “I just didn’t want to be in pain anymore.”

Miller continued to drink to numb his suffering and deal with his illness the best he could. But a year later, during his junior year, he again attempted to die by suicide. He was in Charlotte at his uncle’s house, and a friend of his uncle’s found him sprawled across a bed and called 911. He was rushed to an emergency room where doctors pumped his stomach. Miller said he was angry when he awakened. “It was a drag to try to make it through the day a lot of the time, to pull myself out of bed and show up for people, or show up in front of people,” he said. “You add the voices on top of that, voices telling me I’m not worthy, and I shouldn’t be here. It was rough.”

“I had to own it”

Despite drinking alcohol regularly and maintaining an active social life during his final two years at UNC, Miller said he made his best grades. To graduate on time, he took heavy course loads his last four semesters and went to summer school. “I was a functioning alcoholic,” he said. “I was making good grades, so I was perceived as successful, but inside I was in shambles.”

After graduating with a degree in Afro American studies and sociology, Miller spent two years taking graduate classes at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, with intentions of applying to dental school. But he didn’t want to be a dentist and eventually realized he was just trying to fulfill the dreams of people back home.

In 2017, Miller stopped attending UNC-G and returned to Charlotte, where he worked for his uncle as office manager and a community support specialist. Miller said he didn’t feel fulfilled, and the voices inside his head were growing louder as his emotional pain became more acute.

“I’ve tried this three times, and I can’t even kill myself,” Miller recalled thinking. “How messed up do you have to be that you can’t even kill yourself? I just sat there and cried for about two hours.”

One night, after he’d been drinking all day, Miller decided to try again to end his life. This time he decided to shoot himself with a gun he’d purchased years before for protection. “A lot of times when people think about suicide, … they think it’s the cowardly way out, it’s weak or it’s selfish,” he said. “I can honestly attest that … I wanted the emotional pain to stop. It wasn’t about me not thinking of everybody in my life; I felt like a burden to them. I know now it’s illogical, but at that time it made perfect sense to me.”

Miller put the gun to his head and pulled the trigger. The gun jammed.

“I’ve tried this three times, and I can’t even kill myself,” Miller recalled thinking. “How messed up do you have to be that you can’t even kill yourself? I just sat there and cried for about two hours.”

The next morning, Miller called Jasper and told him about his suicide attempt. The two reconnected, and Miller resumed his weekly meetings. He also started taking his medications regularly for the first time since his diagnosis. “I realized that mental illness is something I’ll have to live with for the rest of my life, and I had to take it seriously, and I had to own it,” he said.

The color of mental health

Once stable, Miller came to the realization that his calling was to help others with mental illness. About eight months after his third failed suicide attempt, he enrolled in a master’s program in clinical mental health counseling at Montreat College. Miller said the program had only three Black professors and few students who looked like him. At Carolina, Miller said he’d been reluctant to go to the University’s Counseling and Psychological Services because he didn’t think he would be seen by a Black doctor, someone to whom he could relate.

CAPS staff see an average of 20 to 30 students a day and ask whether they have a preference in terms of identity and background of the therapist they see. Officials accommodate those requests when possible, according to CAPS officials. The CAPS Multicultural Health Program tries to be intentional about the needs of students of color and is committed to decreasing mental health stigma while increasing access to culturally responsive mental health support and services, officials said.

“Even when I was in my master’s program and they were teaching stuff about how to be a good therapist, I was like, ‘How is this going to work in the ’hood?’ ” Miller said. “My teachers couldn’t answer, so I said, ‘I’m going to take what you teach and bring my own flavor, my own culture to it.’ ”

After earning his master’s degree, Miller opened a practice in Charlotte that includes other counselors and a licensed family nurse practitioner who prescribes medication. A large percentage of the patients seen at Miller’s practice are Black. “I’ve had people come in and tell me they feel better with someone that looks like them; the staff looks like them,” Miller said. “It feels like they’re receiving care not only from someone who looks like them but from someone they feel really cares about their treatment, and I think that goes a long way.”

UNC’s Meltzer-Brody said such an approach is needed in treating patients. “It’s important that we have equity in mental health to ensure we meet patients where they are and support the best outcomes,” she said.

During the 2022–23 academic year, UNC’S Counseling and Psychological Services program saw 1,523 white students, 595 Asian American or Asian students, 360 Black students, 237 Hispanic/Latino/a students, 169 multiracial students and 98 Native American students, according to information supplied by UNC Media Relations.

Since opening the practice, which has a waiting list for new patients, Miller hasn’t looked back. Today, the man who was once afraid to admit he has a mental illness now travels nationally and internationally telling his story. Every May he holds a mental health awareness day that involves a walk and a fundraising gala. This year’s event is being held May 18 at the NASCAR Hall of Fame in downtown Charlotte.

Miller wrote the book Injured Reserve: A Black Man’s Playbook to Manage Being Sidelined by Mental Illness, which chronicle’s his life and bipolar diagnosis, while challenging the stigma of mental health in Black communities and providing solutions on how to seek help. Miller worked as the mental health expert on the global wellness team for Twitter, now known as X, until the position was phased out in November 2022, a month after Elon Musk bought the company.

For eight years, he’s partnered with DeVetta Holman-Copeland ’79 (’85 MPH), coordinator of resiliency, student development and academic success in UNC’s Office of Student Wellness, for the event “Let’s Talk About It,” which discusses how to remove the stigma in Black communities of seeking help for mental illness and gives students a chance to discuss how mental health affects their lives. Holman-Copeland said students easily relate to Miller because of his honesty and transparency.

As word spread about Miller’s practice and methods — he has a PlayStation in his office to engage younger clients and meets adults outside his office if it makes them more comfortable — it attracted more clients. Micha James, a Black single mother, first heard Miller speak about his mental illness when Miller participated in a virtual program sponsored by Blue Cross Blue Shield.

“It was the straitjacket and the bottle of Patrón that piqued my interest, because that’s not what you typically hear,” James said. “I was initially struck by him being a Black male and talking about mental health, because we don’t talk about it in our community.”

James had been searching for a therapist for her son, Michai, and thought Miller would be a good fit. Her son wasn’t presenting any mental issues, but mental illness runs in her family and in her son’s father’s family. “Mr. Miller was somebody for him to talk to, to be honest with, somebody who would be honest with him,” she said.

James said she could tell a difference in her son, now 19 and in college, after he started seeing Miller, who showed up, unannounced, at her son’s state championship football game in Kenan Stadium and later at his high school graduation. “He didn’t just show up to say he was there, but he stayed until the end,” she said. “That was appreciated. I wish we had more people doing the work that Rwenshaun’s doing, and I wish we had more Black men doing it.”

“Part of who I am”

Miller has shared his story via a TED Talk, on Instagram and through other social media platforms. He discloses part of what he’s been through to his clients so they know he understands what they’re going through. (Photo: Ted/Youtube)

Miller has shared his story via a TED Talk, on Instagram and through other social media platforms. He discloses part of what he’s been through to his clients so they know he understands what they’re going through.

Meltzer-Brody of UNC’s psychiatry department said sharing stories is “very helpful and very courageous.” Universities, she said, are doing a much better job of education and expanding resources, particularly after the incidence of mental health issues spiked during and after the COVID pandemic.

“It has to be something that we teach our kids,” Meltzer-Brody said. “We need to provide them with mental health literacy that begins in grade school and help them realize that psychiatric illness is common and that reaching out for help will lead to much less suffering and much improved outcomes.”

In retrospect, Miller said he now realizes he should have sought help much sooner than he did. He markets an original T-shirt that says, “Be Who You Needed When You Were Younger,” and another that says, “Check on Your Strong Friend,” with the word strong crossed out.

He also spends time counseling children at Hidden Valley Elementary School in Charlotte, and where he grew up in Bertie County — both pro bono.

“Mr. Miller quickly built a good rapport among the students, and they gravitated to him like he was a celebrity,” said Corey Gaines, a counselor at Hidden Valley. “He sees 12 of our students either individually or in group sessions. What he’s doing is invaluable. He’s changing the narrative.”

Casey Owens, CEO and executive director of the Bertie County YMCA, has been friends with Miller since elementary school but lost touch with him when they graduated from high school. Years later, Owens heard Miller speak at a YMCA summer camp about what he’d been through, and Owens said he cried. The longtime friends spoke privately afterward, and Owens thanked Miller for opening up and encouraged him to continue sharing his experience with mental illness.

Miller said he now realizes he should have sought help much sooner than he did. He markets an original T-shirt that says, “Be Who You Needed When You Were Younger,” and another that says, “Check on Your Strong Friend,” with the word strong crossed out.

Miller intends to do just that — and to remain healthy. In a daily journal, he keeps track of his interactions, how he spends his leisure time, his feelings and what he consumes.

“Consumption is not just food and water,” Miller explained. “The things I watch on TV, the people I talk to, how I feel before I talk to them and after I talk to them. Exercise. I have journals from six, seven, even eight years ago just to see my progress and to see things I need to stay away from.”

Miller also sponsors adult coloring parties as stress relievers and meditates and practices yoga. “I know now that bipolar disorder is just a part of who I am,” he said. “It’s not a totality. I was given this experience to create better experiences for others.”

If you or someone you know is in crisis or needs help, please call or text 988 to connect with the National Institute of Mental Health’s 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. The Lifeline provides 24-hour, confidential support to anyone in suicidal crisis or emotional distress.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.