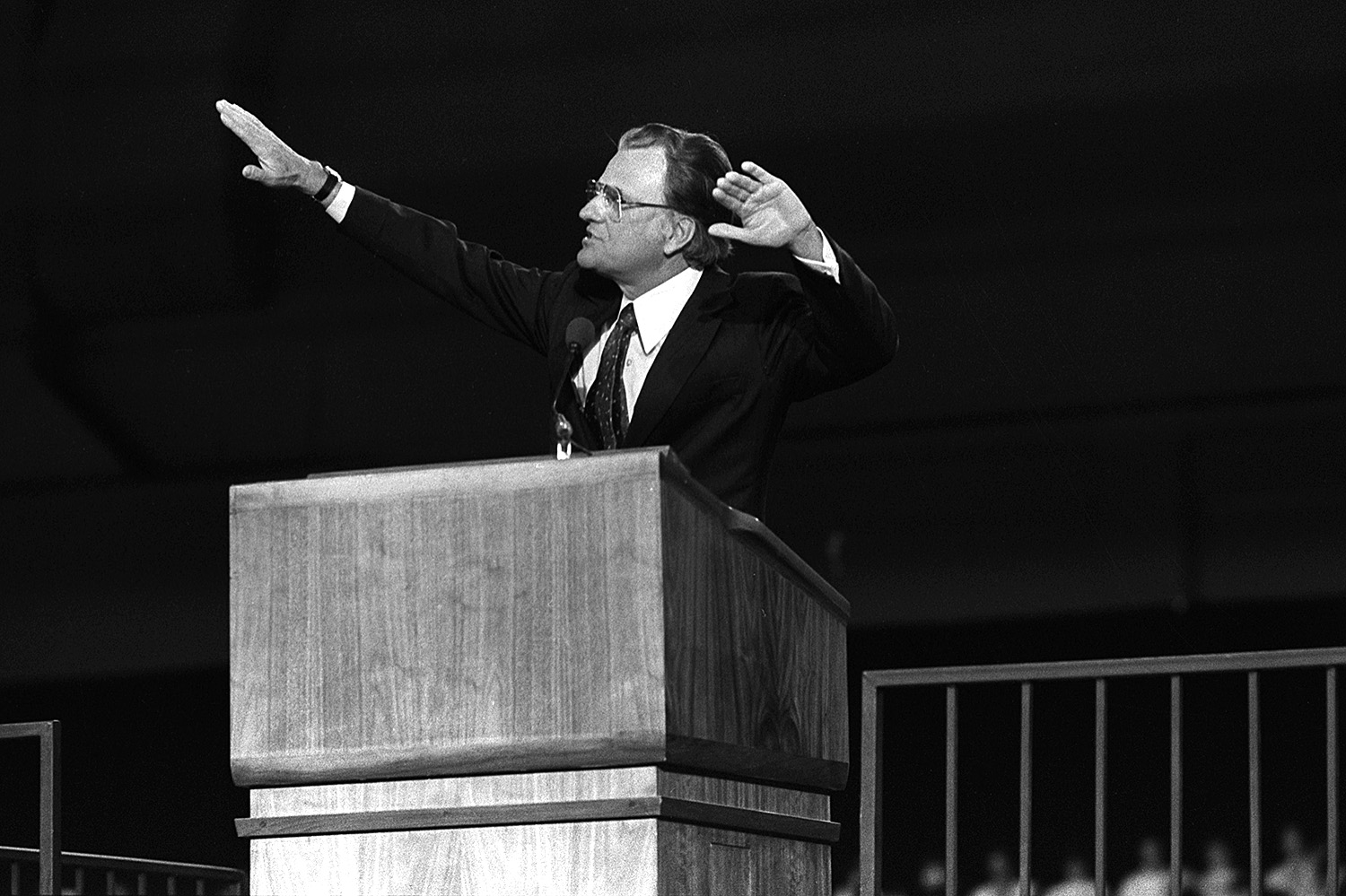

Billy Graham as Cultural Icon

Posted on Jan. 9, 2019

More than 68,000 people showed up over four days in 1978 to hear Billy Graham speak in Las Vegas. He ”meant so many different things to so many different people,” Michelle Robinson said. “He’s a pastor who we can understand in the evangelical tradition, but he’s also an American cultural icon that we can look at through so many different lenses.” (Las Vegas Review-Journal photo)

“Spiritual giants don’t come to Las Vegas.”

That’s how one local pastor dismissed Billy Graham’s plan for a spiritual revival in Sin City, according to an oral history housed in the Billy Graham Center Archives. But Graham did come, and he drew more than 68,000 souls to the Las Vegas Convention Center during the four days of his 1978 crusade.

Michelle Robinson, associate professor of American studies, is drawn to moments when cultural worlds collide in strange and unpredictable ways. (Photo by Grant Halverson ’93)

Michelle Robinson, associate professor of American studies, is drawn to moments like these, when cultural worlds collide in strange and unpredictable ways. The evangelical preacher on the Las Vegas strip; ethical dilemmas in stand-up comedy; the influence of detective stories on great literature. Her scholarship tends to focus on people and ideas that don’t fit the expected narrative.

With the death of Billy Graham last year, Robinson’s research on the North Carolina-born evangelist and his cultural legacy has taken on a new resonance. In a time of sharp divisions in both the evangelical movement and the national media landscape, she’s interested in Graham as a public figure who transcended narrow categories and achieved a level of fame usually reserved for pop stars and presidents.

“Billy Graham meant so many different things to so many different people,” Robinson said. “He’s a pastor who we can understand in the evangelical tradition, but he’s also an American cultural icon that we can look at through so many different lenses.”

Robinson has a specialty in American religious history, but her interest in Graham isn’t limited to his theology or his impact in Christian communities. She sees him as one of the 20th century’s biggest multimedia stars, able to command vast audiences in churches, over the radio, on movie screens and in print. “Billy Graham has probably spoken to more people in the world than anyone who ever lived,” she said. “Jesus has spoken to many more people in their hearts, but Billy Graham has spoken to more in person.”

Part of the discipline of American studies is thinking about cultural messages and how they’re shaped and shared. So Robinson studies Graham as both a religious thinker and a gifted performer. She sees him as a famous Southerner who brought a particular set of manners and mores to a worldwide following. And she admires him as a canny code-switcher, comfortable planning a visit to the White House or a crusade among the casinos of Vegas.

“One of the things that interested me about Billy Graham is the question of why he was important to different communities. His message was enduring, but there was a flexibility to him, as well, in terms of understanding the nature and fulfilling the aspirations of different communities when he traveled across the United States.”

In Las Vegas, that flexibility meant working with the political and business titans who profited from the city’s biggest industries. Graham was able to win support not only from churches and civic organizations but from people whose livelihoods rested on traditionally un-Christian vocations. Robinson highlighted those unlikely partnerships in a book chapter about Graham in Las Vegas.

“In their preparations for Billy Graham’s visit, crusade organizers developed strategic and mutually beneficial partnerships with casino executives,” she wrote in the 2018 volume All In: The Spread of Gambling in Twentieth-Century United States. “Graham’s visit brought new converts to the fold, drew attention to the presence of evangelicals in the casino-resort complex, and, by cultivating support from the chamber of commerce, tempered the most pejorative views of the Las Vegas Strip.”

To figure out the details of those alliances — the negotiations among local churches, the strategizing about media and outreach, the lingering impact of Graham’s crusades on the culture of a place — Robinson has done extensive work in the Billy Graham archives at Wheaton College in Illinois. “The collection is so vast that there’s enough for everyone in the world to do a project on Graham,” Robinson said. “Like every piece of paper he touched or that somebody around him wrote. It’s incredible.”

All of the time reviewing Graham’s life and work has given Robinson new avenues to explore. “A successful day in the archives is when you don’t want to go to lunch. Because everything you’re seeing — the letters that you’re looking at, the conversations that you’re getting to eavesdrop on — everything is so intriguing. I’m interested in really doing sound archival work to understand how people lived and believed and built communities.”

Robinson is considering a project on religious identities in different regions of the U.S. — how the same official faith can have wildly varying expressions across the country. She also wants to dive deeper into the rise of mega-celebrity in American life and how it has influenced so many strands of modern culture. At a time when politics and entertainment seem to be converging, exploring the links between stardom and public life looks especially promising.

“It would be fascinating to teach a class called 20th Century Icons and put someone like Billy Graham next to an FDR or next to a Frank Sinatra or Yoko Ono, and see how we think about different kinds of celebrity or notoriety over time,” she said. “That would be a great class.”

— Eric Johnson ’08

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.