Doors No Student Should Have to Open

Posted on Sept. 25, 2023by Ira Wilder

(Photo: Carolina Alumni/Cory Dinkel)

There are thousands of doors on campus I never think of opening. Doors I have no reason to enter. Doors I expect hold no purpose for me. Doors that lead to obscure offices or electrical rooms or closets.

And, truthfully, I had never seen the inside of a closet on campus before Monday, Aug. 28, when a storage closet in Greenlaw Hall, near the Pit, became my safe haven.

Greenlaw 101 is the classroom assigned to my public policy capstone class. It meets Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, at 12:20 p.m. I’m a senior, and this is the last class in my public policy major. I’m also a journalism major and spent the first three years working for The Daily Tar Heel, where I was prepared to write a story or grab my camera whenever news broke.

On that Monday, before any phones buzzed or emails pinged, the television screens, on which the professor presents lecture slides, suddenly issue a warning that I’d seen before only on the news:

“Police report an armed and dangerous person on or near campus.”

No one immediately springs into action. It takes minutes before the situation sinks in. Students remain in their seats. Some crack a few jokes. Some continue piddling with their work. But, then an Alert Carolina message from the University crosses our phone screens. We now know the danger is real.

Our professor runs to the door, pulls students in from the hallway and advises us to move away from the front door. Some students dismiss the request and leave. Others move toward the front of the classroom, away from the door. But before I know anything else, my body pulls me with about a dozen students into a storage closet within the classroom. It’s an automatic movement, as I take a bet I’ll find safety behind the door.

Ira Wilder is a senior from Henderson, majoring in public policy and journalism. He is a Morehead-Cain Scholar and an intern for the Review. (Photo: Carolina Alumni/Cory Dinkel)

We feel silly at first, entering a door we pass by without noticing three times a week. Our migration seems an erratic, desperately dramatic action. We are sure it’s a false alarm. We are sure we will be out in a few minutes.

We close the door and settle onto boxes of toilet paper and floor scrubbers. I sit on a side table. We huddle amidst brooms, mops and abandoned chairs. The quarters are tight. The shoulders of those seated rub the thighs of those standing. We refresh our phones, looking for details, for names and for locations.

Greenlaw Hall is in the center of campus, about a dozen steps away from the Pit. We are on the first floor. Three doors separate us from the heart of campus.

One of us receives a text that someone was shot in Caudill Laboratories. The building is separated from Greenlaw by the temporarily empty Bingham Hall and Wilson Library.

The room falls silent. We cannot conjure words to describe the empathy and the panic we begin to feel. “I never thought it would happen here,” one student whispers.

We hear sirens through the cinder block walls. One student offers us anxiety pills. I don’t take one, a decision I later regret.

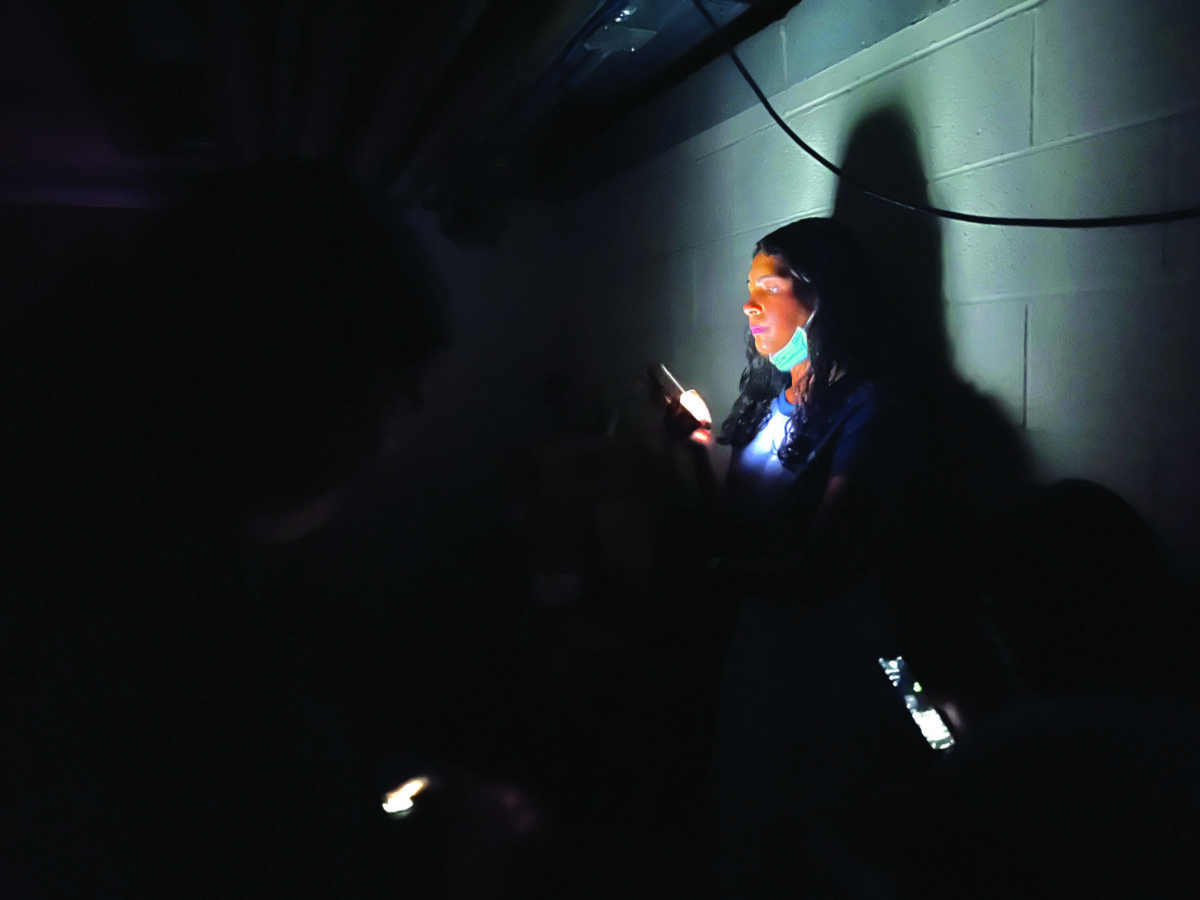

We decide to turn off the fluorescent lights, and suddenly we are thrown into a dark silence, our faces illuminated by the dim glow of our phones. Someone turns on an online police scanner. Most of us text our parents.

My parents receive a text from me, wherever they are. “There’s an armed shooter on campus; I am in a storage closet in a classroom.”

I’m sure it’s a text no parent ever wants to receive. My dad, a former Marine, replies in minutes and offers survival tips. He tells us to barricade ourselves in and to stay low. My mom, an alumna who graduated in ’92, relays updates from television news and tells us to be safe and smart. “It will all be ok,” she texts.

No one knows who the victim is. No one knows how many victims there are, if any. At one point, we hear two people are dead and 10 people are wounded.

I know two people in the closet by name, but the rest are essentially strangers. Though we are unfamiliar to one another, we are unified in confusion. I start getting texts from friends, mostly some form of “Are you okay?”

“Are you physically safe? God, I cannot imagine, I am thinking of you,” one text says.

I text friends, partly making sure they are OK and partly making sure I am not facing this tragedy alone. “We’re terrified,” I text to one friend.

“It’ll be okay,” he replies. “Just keep taking a breath in and out.”

Tar Heels are unquestionably united when we face tragedy. Loss on campus is not easy. Tragedy strikes like a snake bites an ankle: It is unexpected; it stings; and it pulls us out of autopilot.

While huddled in a storage closet in Greenlaw Hall, students checked their phones for updates, not sure what to believe. (Photo: Carolina Alumni/Ira Wilder)

In the closet, I think about when we lost three students to suicide in September and October 2021. The only way we got through it was by supporting one another, by having difficult conversations about mental health, by understanding that we are all part of a whole.

Initially, there is a lot of conflicting news. We’re not sure how many people have been wounded, how many people are dead, how many shooters there are, but we are almost certain shots were fired in Caudill.

Within the first half hour, we learn someone is handcuffed, but apparently it’s the wrong guy. Our sense of relief fades, and we realize we’ll remain in the stuffy closet longer. We sigh and inhale the faint smell of cleaning chemicals, most of our backs pressed against the cold walls.

We are not sure what to believe. The only thing we are sure of is that we fear for our lives. I hold my knees and press my chest to my thighs, trying in vain to pass the time. We hardly speak, but we can see it on one another’s faces: the look of disbelief, of trepidation. We are in a classroom in the center of campus. If an outside shooter were to wander into a random classroom, it could very well be this one.

We fall quiet for the first hour, hoping our silence will give us time to hear and prepare for an intruder.

I am the first to cry. Not necessarily because of fear, but because of those who might be hurt, those whom I have not checked on by text yet and those whose lives might be shattered. I can barely breathe. I am less concerned that I could die and more concerned about my classmates who are not in the closet with me.

This class began just a week ago, so the people I’m shoulder-to-shoulder with are all but strangers. Someone to my right hears my whimpering and hugs me without asking. An hour later, I return the hug, when, in the dark, I hear the heavy breathing that only accompanies tears.

As we approach the second hour, a professor emails a student in the closet to attend a remote class. We whisper and then giggle about the nerve it takes to make such a request. It’s the most lighthearted thought we’ve had since we crossed the closet’s threshold. It relieves some of the stress, if for just a moment.

I realize I have not moved my legs since I first sat down. I have to pull them out of entropy with my hands, straightening my knees forcibly. Some students trade spots, alternating between standing and sitting.

Passing the time in silence is not easy. Some listen to music on their headphones, some opt for podcasts. I find it impossible to do anything but text my loved ones and refresh X, formerly known as Twitter, for updates. I watch videos of police cars flooding South Road. I see a video of armed officers searching a building. I see a photo of a suspect, posted by UNC Police.

We hardly speak, but we can see it on one another’s faces: the look of disbelief, of trepidation. We are in a classroom in the center of campus. If an outside shooter were to wander into a random classroom, it could very well be this one.

Around the third hour, we get texts that police are evacuating buildings. A student somewhere on campus has a neighbor who works for the FBI, and she texts us the protocol for building evacuation. (Two officers will come to the door. They will slide their IDs under the door. You will call 911 to confirm that the person on the other side of the door is whom he or she claims to be.)

Someone in the blackened closet remarks how much more scared we would be if we didn’t have the internet to connect us to the outside world. Though this is true, the connectivity comes with a price — terrifying false information. Instead of agreeing, I remark I’m grateful the closet is air-conditioned.

Our professor, still in Greenlaw’s large lecture hall, knocks on the closet door and tells us officers have arrived at the building. We emerge from the closet and reunite with students in the lecture hall. I share hugs with classmates whom I have never touched before. It feels strange, but it’s a welcome comfort. It’s a reminder that we are all simply humans in a scary world. And truthfully, all the comfort we have is in one another.

At 4:15 p.m., more than three hours after that first alert message came across the classroom screen, we are given an all-clear. Students descend on the quad — from the storage closet, from adjoining classrooms, from other buildings. I feel naked, as if it’s wrong to be in the open air.

I hear that UNC Police Chief Brian James said in a press conference that one faculty member has been killed. One victim is one too many.

Helicopters buzz overhead. I walk down Cameron Avenue, the Old Well receding behind my back. The campus feels shattered.

Buses aren’t running, so thousands of students walk down the street toward their dorms and homes. I have never seen this many people on Columbia Street during daylight. The majority of us press phones to our ears, informing our family and friends we are safe.

As we slowly leave the crowd and melt back into our dorms and apartments, we are a dwindling team. We seek refuge in distant grown-ups. And despite our rent payments, our driver’s licenses and our tax forms, for a moment, we are children again, scared of the University we love, realizing that we have taken our campus — and its doors — for granted.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.