Human Sexuality Counseling — A Look Back

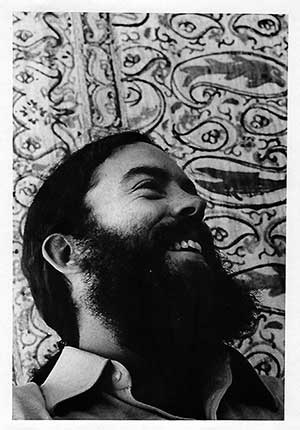

Reid Wilson ’73 started the Human Sexuality Information and Counseling Service at Carolina. COURTESY OF REID WILSON ’73

When Reid Wilson ’73 was in high school, his girlfriend became pregnant. The teens were scared because they knew they weren’t ready to be parents and were unsure of what to do. There were no legal abortion clinics at the time, so his girlfriend and her father flew to London, where the pregnancy was terminated.

A few years later when Wilson was a Carolina student, he served as the administrator of a course on human sexuality taught by Takey Crist ’59 (’65 MD). “It was an incredibly popular course,” Wilson said.

The course, and his experience in high school, led Wilson to start the Human Sexuality Information and Counseling Service at Carolina. The group, which operated out of the second floor of the student union, offered a place where students could visit or call to ask questions and receive information and counseling on sexual matters and contraception. “I didn’t want anyone to go through what I went through because of a lack of information,” Wilson said.

The HSICS received student government funding and opened in October 1971. Counselors bought a table, chairs and bookshelves, which held free pamphlets and books, as well as displays of anatomy and contraceptive devices, according to a master’s thesis by Kelly Morrow ’06 (MA, ’12 PhD), which included a section on HSICS. Wilson hung his Indian-print bedspread (see photo at right) as a partition for privacy, Morrow wrote.

In May, 16 HSICS counselors gathered in Carrboro for the organization’s 50-year reunion. Wilson, a psychologist in Chapel Hill who treats anxiety disorders, couldn’t attend in person but participated via Zoom with four other counselors. For some, it was their first time reconnecting in decades.

As they enjoyed light hors d’oeuvres, wine, bottled water and each other’s company, they reminisced about being bold enough, as students, to provide other students information on sex and contraception when talking about such subjects was considered taboo in most American households.

Not all of the counselors were students. Alice Carlton ’76 (MSW) came to Chapel Hill with her husband, a UNC grad student. She was running a daycare center, but, she said, “I was still finding my path.”

The couple saw an ad in The Daily Tar Heel that said a group of students were starting a volunteer counseling service in human sexuality. “I was a young woman who was interested in that topic,” Carlton said. “Through HSICS I found that I liked helping people, so I decided to get a master’s degree in social work and ended up with a 40-year career as a clinical social worker.”

Carlton enjoyed being an HSICS counselor but admits not realizing when she was younger how important it was to offer a confidential means for students to get information about sex and contraception without fear of being shamed.

Esquire and Time magazines considered the service groundbreaking enough to publish stories about it. “By dialing 933-5505, University of North Carolina students can get confidential information about pregnancy, abortion, contraception and sexual and marital relationships,” Time reported in August 1972. “More than 30 trained volunteer counselors answer 50 calls a week, with at least one man and one woman always on duty so that shy callers can consult with someone of their own sex.”

While national magazines took note, University administrators didn’t initially embrace the student-run service. They neither pushed back against the idea nor fully welcomed the counselors, said Wilson, who served as HSICS director during his junior and senior years.

“The University just didn’t want to deal with it,” he said. “They didn’t want to acknowledge that students were having sex.”

Bruce Baldwin, a therapist with the UNC Student Health Service at the time, was eventually appointed as the liaison between HSICS and the University, Wilson said. One year after the service was formed, gay men were also trained as counselors.

In 1973, HSICS and several co-sponsors, including N.C. agencies such as the State Board of Health and the State Department of Social Services, held the N.C. Workshop on Problem Pregnancy. Attendees were given information on resources inside and outside the state for adoption, family planning and abortion services, Wilson said. At that time, some North Carolina hospitals provided abortion services, but most known abortion clinics were in Washington, D.C., or New York City, he said.

Some prominent UNC students were also interested in becoming HSICS counselors. One was Emily Kenan ’73, whose great uncle was William Rand Kenan Jr. (class of 1894), a major University benefactor whose family name adorns the football stadium. Kenan, a retired licensed clinical social worker living in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, said her relatives were aware of her HSICS involvement but the subject didn’t often arise. She had some conversations about HSICS with her Uncle Frank Hawkins Kenan ’35, all of which were cordial, she said.

“Believe me, if he or my mother had said, ‘You’re out,’ it would have been tough,” Kenan said. “But even if they lacked understanding of our organization, they had respect. We students were a reflection of our times, came from all walks of life and felt there was such a need for this that nothing was going to stop us.”

Kenan noted the organization formed just after the ’60s, a time of anti-establishment sentiments. “Students didn’t really trust adults or want to talk to them, but they trusted us and talked to us,” she said. Counselors provided information on contraception but didn’t tell students what to do, she said.

After HSICS had been operating for a while, Carlton said, she and other counselors noticed a pattern. “The girls would call on Friday to ask about birth control, and the boys would call on Monday to ask about morning-after treatment,” she said. “There were a lot of questions about birth control because not everybody knew about it.”

Judythe Dingfelder ’77, a School of Nursing graduate, was married to an OB-GYN physician when she served as a counselor. “I thought being able to help people in this circumstance was very important,” she said. “I grew up in a home where my parents talked about this type of stuff all of the time. There’s nothing dirty about sex.”

Dingfelder alluded to what was then the anticipated U.S. Supreme Court ruling that would strike down Roe. v. Wade. “I think we’re pretty pro-choice in this country,” she said, “and I think we’re going to find that out when all of these laws are passed.”

Leif Robert Diamant ’71 (’73 MEd) succeeded Wilson as HSICS director. “HSICS tried to help keep people from getting pregnant, told them what they could do if they got pregnant, provided information about STDs and even told people it was okay to enjoy the pleasure of having sex,” he said.

Victor Schoenbach ’75 (MSPH, ’79 PhD) became an HSICS counselor in the spring of 1972. That fall when he enrolled in graduate school, he began giving lectures in residence halls and distributing handbooks on birth control and STDs.

He remembers placing booklets with information on various kinds of birth control and how to access it in a box at the entrance to the undergraduate library and taping a poster on the wall to draw attention to them. He also distributed booklets to some residence halls.

“HSICS was a foundationally important activity at a pivotal time in the history of sex education, particularly on college campuses,” Schoenbach said. “I was proud and extremely grateful to be part of it.”

In 1982, HSICS began to operate under the name Sexuality Education and Counseling Service. HSICS counselors aren’t sure when the organization disbanded.

— Laurie D. Willis ’86