Master Class

Posted on May 5, 2017

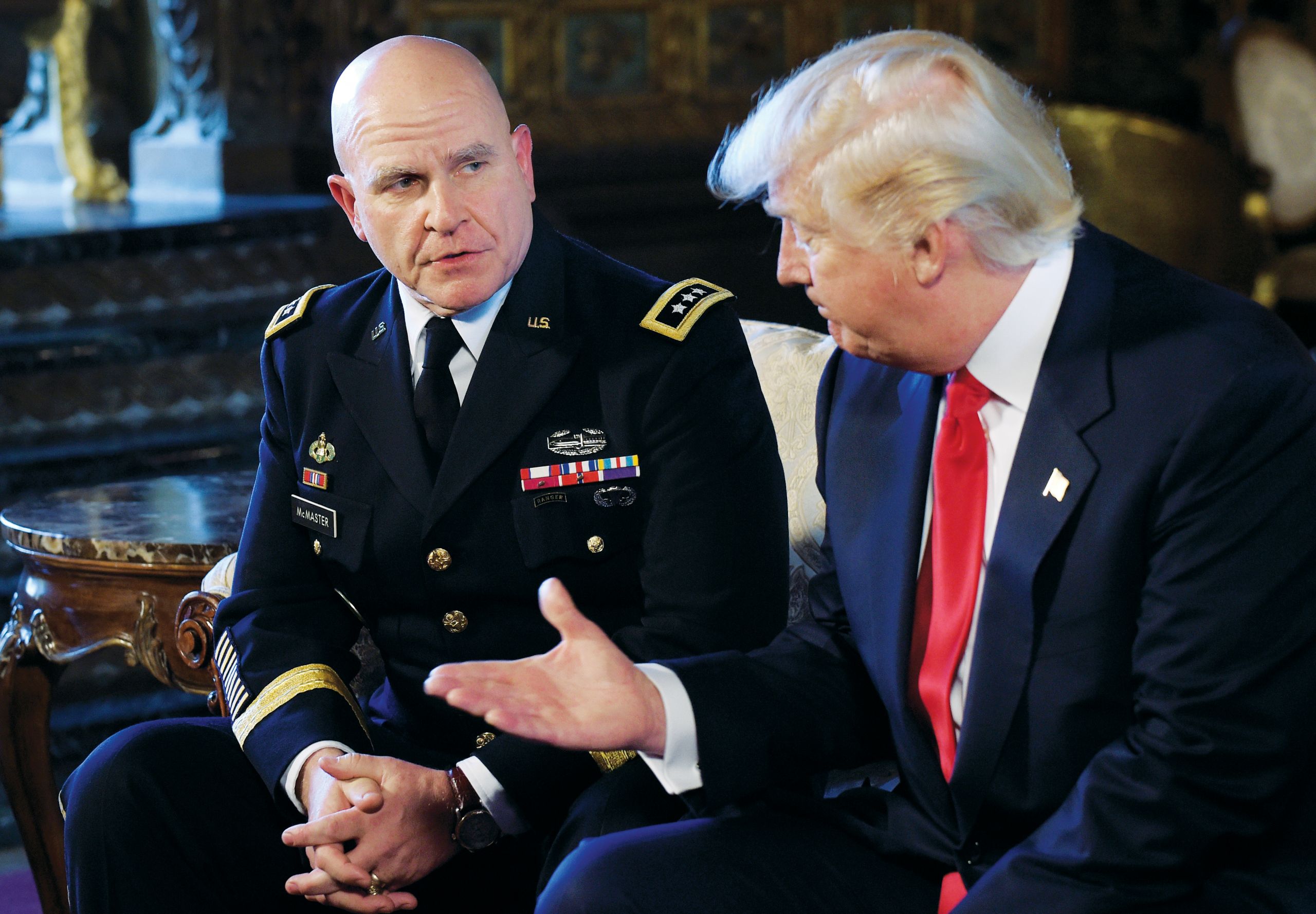

President Donald Trump and H.R. McMaster at the Feb. 20 announcement. It marked the first time senior military officers have held the positions of national security adviser, defense secretary and homeland security chief at the same time. (AP Photos/Susan Walsh)

The president’s national security adviser impressed his Chapel Hill teachers as a warrior and as an intellectual. They’re certain he’ll need both skill sets in the White House.

by David E. Brown ’75

He was a “firecracker” who overworked assignments and loved a lively argument with professors and classmates alike. In an academic program full of highly motivated people — especially fellow military officers — he was rated at the top.

He came to Chapel Hill an Army captain with a bold idea for a master’s thesis. When he left, the people who read it wondered whether he had torpedoed his career. It became a best-selling book. And he has the three stars of lieutenant general on his shoulder.

Those same people have high hopes and great expectations for H.R. McMaster in the hypersensitive job of national security adviser. They’re wondering again — not about whether he’s smart enough or has keen enough instincts or can make critical decisions under fire, but whether he can survive disagreements he might have with the commander-in-chief.

“It’s rare to have the combination of qualities that made you outstanding on the battlefield and also the patience to sit and write history with primary sources,” said Tami Biddle, who taught McMaster in a UNC-Duke joint program in military history as he pursued his 1994 master’s degree and subsequent 1996 doctorate.

“He was clearly on the fast track, on the way to being a rising star in the Army. He dove into the work and never looked back.”

Michael Hunt, professor emeritus of history, recalled: “I think what everybody else has commented on — he’s a very bright guy. He took a seminar with me on U.S. foreign relations, and I think he came out as the best performer in the class. I usually don’t give out straight honors, but he got one. I was quite impressed by his performance.”

Hunt added: “I wonder if Jimmy the Greek is putting odds on H.R.’s prospects” of long-term employment, given McMaster’s reluctance, as well as President Donald Trump’s, to back down.

On Feb. 20, Trump appointed McMaster, with whom he had no previous ties, to replace the ousted Michael Flynn after Flynn was found to have held back information that he had talked with Russia’s ambassador. It is the first time senior military officers have held the positions of national security adviser, defense secretary and homeland security chief simultaneously.

Biddle, Hunt, former Duke professor Alex Roland and classmate Wayne Lee — who now heads Carolina’s curriculum in peace, war and defense — all call him “H.R.” All except Hunt remain in touch with him. Lee and Biddle, a professor of national security studies at the U.S. Army War College who has been teaching senior Army officers for 16 years, were talking with McMaster about his next career move shortly before the appointment.

‘Tell them we can’t stop’

In February 1991, McMaster was in command of a unit that made tank battle history in the Persian Gulf War, helping make the Battle of 73 Easting a standard in attack strategy classrooms.

He was supposed to locate the enemy, report what he found and fall back. He was not supposed to advance beyond 70 easting (a north-south coordinate line measured in kilometers). When McMaster reached that point, he received a radioed warning from a subordinate.

“I responded, ‘Tell them we can’t stop. Tell them we’re in contact and we have to continue this attack. Tell them I’m sorry,’ ” McMaster recalled in a blog post in 2016. “We had surprised and shocked the enemy; stopping would have allowed them to recover. As Erwin Rommel observed in Infantry Attacks: ‘The man who lies low and awaits developments usually comes off second best. … It is fundamentally wrong to halt — or to wait for more forces to come up and take part in the action.”

The Army awarded him the Silver Star for performance in action against the enemy. That’s what he brought with him to graduate school. That, and his thoughts about the way Washington had handled Vietnam.

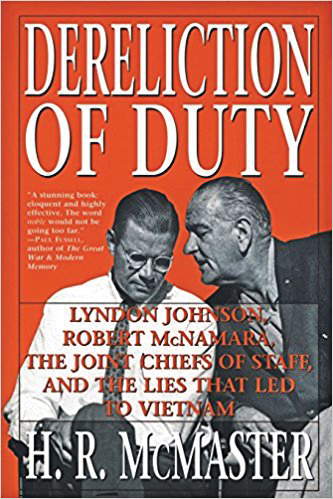

McMaster’s 1997 book was adapted from his thesis and doctoral dissertation.

“I wondered how and why Vietnam had become an American war — a war in which men fought and died without a clear idea of how their actions and sacrifices were contributing to an end of the conflict. When I arrived at Chapel Hill, North Carolina, in 1992 to begin my graduate work in American history, I began to seek answers to those questions,” McMaster wrote in his 1997 book, Dereliction of Duty: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam, which was adapted from his thesis and doctoral dissertation.

“I was overwhelmed with the amount of work he did,” Roland said. “His appetite for hard work is just incredible, and he’s a very smart guy. He can absorb enormous amounts of research material. I advised him not to do it in the way he was doing it. He had a compelling accumulation of evidence. But it was very confrontational and very in-your-face, and it said that the whole Joint Chiefs of Staff had been guilty of dereliction of duty.

“I mean, he hadn’t quite settled on that thesis with that confrontational language yet, but it was very obvious what he was concluding and what he was arguing. And we said that this is likely not to be career-enhancing. It showed not only the prodigious research skills but a willingness to marshal that evidence in support of a very aggressive and troubling conclusion from the point of view of the Army.”

Biddle said: “Without question, a bold thing to do. I suspect he knew he was risking his career.”

Military officers who aspire to teach at West Point are sent to get a master’s, and that’s the direction McMaster was heading. He left Chapel Hill after two years, having packed the doctoral class work into that time, and two years later he had polished the thesis into a dissertation.

“Three years is fast for the PhD,” Hunt said. “Two years is very fast.”

“He was extremely productive — very, very energetic,” said Lee, who was in the joint military history program on the Duke side. “He would generate hundreds of pages in assignments that were 40 pages.”

Roland said McMaster arrived at full throttle.

“I have this vivid recollection that the first time we ever met we got into a rather unpleasant disagreement that started in class and spilled over after class, and I learned years later that graduate students stayed even beyond that” and carried on the dialogue.

“We had several warm exchanges about the relative merits of scholarly intellectual pursuits and professional military pursuits. He became the quintessential soldier-scholar who is equally conversant in both fields. And he’s used both capabilities to good purpose to become the kind of broadly based, thoughtful, knowledgeable, informed military officer that we imagined in our dreams.”

Roland added: “H.R. is a man who knows his own mind. He listened carefully, as he always does, to our criticisms and advice — and then went right ahead with what he was going to do anyhow.”

Hunt also recalled McMaster’s confident eagerness to go toe-to-toe.

“We had really entertaining, engaging discussions of our differing views. He was very critical of [President Lyndon] Johnson and [Secretary of Defense Robert] McNamara and [national security adviser McGeorge] Bundy, the civilians, and thought the Joint Chiefs had failed to stand up to them and was very critical of the Joint Chiefs. I was pretty direct in challenging him, and he was forceful in his responses. We had really good exchanges. Forced me to think about some issues and, for all I know, it forced him to refine his argument.”

When McMaster made general, Roland was surprised.

“I never imagined that he would be a flag rank officer. And the reason I didn’t was — perhaps it was my own underestimation of the military establishment in general and the Army in particular — but H.R. is an independent thinker, a critical thinker, and he has the strength of his convictions, and he will stand up against the conventional wisdom if he thinks it’s wrong. All my experience with the modern military is that the mavericks like that who think for themselves and are not afraid to speak out — they end up on the rocks.”

His teachers characterized him as never being a careerist — he didn’t seem to care whether something he did blocked his way to a promotion. His attitude was: “If I don’t get it, so be it. I’ll prosper where I am.”

McMaster, who directed Army forces in the Tal Afar offensive in Iraq in 2005, gives first aid to an Iraqi soldier injured when he entered a booby-trapped house. McMaster used a then-controversial counterinsurgency strategy for dealing with militants in Tal Afar. (AP Photo/Jacob Silberberg)

Back to war, and to Washington

After two years at West Point, the Army wanted McMaster back in the “muddy boots” army. And again, he stood out.

As a commander in Iraq, he’s credited with writing the manual on how a strategy of counterinsurgency can be effective against terrorists who plague the civilian populace. One of the persistent criticisms of Vietnam strategy was failure to win the “hearts and minds” of local people who could help a foreign fighting army.

Killing the enemy is only part of a successful mission, McMaster thought. You also have to “clarify your intentions to people by developing relationships, by action, by dialogue with people and by addressing local grievances,” he told a reporter at the time. “This means being out in the city. We could stay in our F.O.B. [Forward Operating Base] and eat mini pizzas and ice cream and redeploy in a year, but that won’t win the war.”

It is this dual military personality — the man who faced off against Iraqi tanks in the desert and hammered them until they surrendered, and the military history intellectual who understands the rules and when to break them and go outside the box — that makes the people with whom McMaster studied fascinated about his prospects for success in the Trump White House.

As Hunt said, “Action heroes and intellectuals” often are opposites.

Wayne Lee wrote an op-ed piece after McMaster’s appointment in which he explained: “They will disagree about the fundamentals of U.S. strategy. In essence, Trump’s strategy for the physical security of the United States against attack by terrorists is ‘body-based.’ It’s a sort of non-lethal version of what the military calls ‘interdiction.’ … His hope is to literally stop every body that might be a threat from entering the country.

“In contrast, McMaster is an expert practitioner of the much more subtle, traditional counterinsurgency strategy, which is based on hope and persuasion rather than fear and interdiction. … Traditional counterinsurgency promotes a vision of a more hopeful future and then protects and supports a wide enough population in a given war zone that the silent majority among them, persuaded by that hopeful message, will provide intelligence against insurgents. … McMaster is wise enough to recognize that total interdiction of individual threats is an unattainable goal — as American attempts to interdict North Vietnam’s support for the guerrilla war in South Vietnam proved.”

McMaster’s naming of a senior official who will write the administration’s national security strategy seems to endorse that philosophy. Nadia Schadlow, appointed in March, asserts in a new book that the U.S. in military interventions repeatedly errs in not following tactical operations with reconstruction.

The Review asked Lee, Biddle, Hunt and Roland how they thought the dynamic between president and national security adviser might play out.

“The problem now is the only people that Trump really seems to trust are billionaires and military men,” Hunt said, “so our best hope to getting somebody with a level head is probably getting a military guy in the [National Security Council]. I hope H.R. can convince him that there’s virtues in a carefully considered policy process.”

Hunt has hopes for the teaming of McMaster with Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and Homeland Security chief John Kelly, both retired Marine generals.

“I think they should be a potent bloc, and you can imagine a cabinet or a crisis meeting. The three of them, I think, would have a great deal of weight if they watch each other’s backs, which they are likely to do.”

When officers leave the military and go into the political environment, Biddle said, “they’re walking into a different world, much less ordered, structured. That complicates his life a little bit, or maybe a lot,” because he still must stay within what she called “military norms.”

“He’s going into a situation that’s very interesting. Basically, the White House is divided into factions, and H.R. is going to have to decide who he deals with. What we have to hope is folks are going to be willing to listen. I’m really rooting for him.”

Roland said: “One of the things I am sure of is he has enormous integrity and willingness to speak truth to power. So he will not do anything in that position that will compromise what he perceived to be his duty, not only as an Army officer but as a citizen.

“He’s also spent 30 years in a bureaucracy that’s difficult to navigate, and he does not lightly challenge authority. He believes in authority. He believes in the chain of command. He has respect for his superiors — their positions, if not their personalities. He’s obviously figured out how to get along with people. I was surprised when he was promoted to general at all, and I kept getting more surprised as he was promoted up to three-star general.

“And that suggested to me that he has a real gift to think independently, to speak his mind and still to learn to get along productively in these very, very tense and contentious cohorts of senior military leadership.”

Lee: “He literally wrote the book on being blunt on giving advice to the president.”

Hunt pointed out that in the first days after his appointment, McMaster “made the rounds at the NSC trying to reassure the staff, kind of calm their anxiety, which sounds very much like him. If their experience is anything like mine, they’ll find an even-keel guy who can follow their arguments and challenge their arguments and synthesize their arguments and present them effectively to Trump. If anybody’s got a chance, I guess he does.

“I really wish him well. I think the situation is a bit dire. I’ve got a fair number of contacts in Washington and the city is just simply — at least on the foreign policy side — I think deeply anxious about what’s going to happen — what a Trump foreign policy’s going to look like. So if H.R. can come in and calm the waters a little bit that will be an accomplishment in itself. And if he’s able to guide Trump along a bit to a safe harbor somewhere then that will be even better. It’s a big job, I think, at a dangerous, anxious time.”

David E. Brown ’75 is senior associate editor of the Review.

More on McMaster

More on McMaster

-

“The Lesson of Tal Afar,” The New Yorker, April 10, 2006.

-

“Harbingers of Future War: Implications for the Army with Lieutenant General H.R. McMaster,” video from the Center for Strategic & International Studies, May 4, 2016.

-

“Trump Gets an Upgrade at National Security Adviser,” The Atlantic, Feb. 20, 2017.

-

“McMaster’s takeaways: Don’t lie, don’t blame the media, don’t rely on an inner circle,” Politico, Feb. 21, 2017.

-

“McMaster As National Security Adviser Is A Good Choice, Exum Says,” NPR, Feb. 22, 2017.

Road to the White House

As of mid-March, three additional Carolina alumni had taken jobs in the Trump administration:

-

Michael “Mick” Mulvaney ’92 (JD), 49, of Fort Mill, S.C., is director of the Office of Management and Budget. He was elected to the U.S. House in 2011, becoming the first Republican since 1883 to represent South Carolina’s 5th Congressional District, a position he held until his confirmation as OMB director.

-

Kristan King Nevins ’13 (MBA), 38, of Washington, D.C., is chief of staff to Karen Pence, wife of Vice President Mike Pence. Beginning in 2006, Nevins served as the chief of staff to former first lady Barbara Bush and later worked for the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy.

-

Ray Starling ’02 (JD), 40, of McLean, Va., is special assistant to the president for agriculture, trade and food assistance. Starling previously was chief of staff for U.S. Sen. Thom Tillis, for whom he worked when Tillis was speaker of the N.C. House, including as Tillis’ senior agriculture adviser.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.