Recipe for Success?

Posted on Sept. 25, 2023Carolina has begun the second year of its IDEAS in Action curriculum, aimed at teaching students everything from time management practices to ethics and artistic expression — and the skills to land a job.

By Eric Johnson ’08

The IDEAS in Action curriculum, which took years to develop and will get years of further tweaking, is Carolina’s best answer to the question of what a modern college graduate ought to know. (Illustration: Haley Hodges ’19)

On a Monday morning in April, two-dozen first-year students met in a basement classroom to figure out what to do with their lives. With more than a few still rubbing sleep from their eyes, the reticent undergrads plunged right into some deep, soul-searching questions.

Should they value money or purpose? Follow a deeply felt passion or strive for work-life balance? What is work-life balance, anyway, and is it even possible? Can you do good in the world and do well for yourself at the same time? “It already feels like time is short,” sighed a young woman with bright pink fingernails and a very large Starbucks cup. “How am I going to figure all of this out?”

Welcome to College 101, or what the University calls College Thriving. It’s a new course for all first-year students, introduced as part of a comprehensive overhaul of the undergraduate curriculum that debuted last fall. Like universities nationwide, Carolina is grappling with how to adapt a broad liberal arts education to the rising demand for job skills and career-focused degree programs.

The IDEAS in Action curriculum, which took years to develop and will get years of further tweaking, is Carolina’s best answer to the question of what a modern college graduate ought to know. It covers everything from study skills and time management to ethical values and artistic expression — and it must somehow speak to the hopes, dreams and financial worries of more than 5,000 new undergraduates who step onto campus each year.

“Our goal is to create a foundation that prepares students to become more curious, to explore disciplines and opportunities they might not otherwise have thought about,” said Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz, who spearheaded the curriculum overhaul shortly after he became dean of the College of Arts and Sciences in 2016. “There’s pressure on students today, and everybody is eager to jump on the career train. What we’re trying to do is not force students to choose a major right away, to give them some time to think and explore. We’re trying to lower the anxiety.”

Debates over curriculum are as old as higher education. The first students at Carolina were obliged to translate Latin and Greek classics alongside the study of mathematics and English literature. Following Reconstruction, UNC added history, metaphysics and logic, moral science and practical agriculture, among many others. Romance studies, economics and psychology would all have to wait until the early 1900s, and other fields took off after the post-World War II boom in enrollment, adding religious studies, statistics, city planning and more.

Writing in 1918, UNC President Edward Kidder Graham (class of 1898) argued that the curriculum is the University’s “medium for expressing its purpose,” representing nothing less than “the historic effort of civilization to create a whole free man.” A good curriculum ought to evolve alongside society’s changing needs, Graham thought, and never become just a set of “more or less worthy and dignified by-laws.”

That spirit of modernization was very much behind the decision to evaluate UNC’s previous Making Connections curriculum, which was more than a decade old and often felt to students like arbitrary box-ticking instead of a thoughtful, purposeful program of study. Guskiewicz said he wanted more than just a light update, so he gave the faculty committee working on the new curriculum a broad mandate. “Many universities start this process, realize it’s not easy or get into battles over content and decide to stick with the status quo,” he said. “We didn’t do that. We really wanted to think about what a 21st-century education should look like.”

Anxiety, exploration and jobs

Back in the basement classroom, Marsha Dopheide, an assistant professor in psychology and neuroscience at the time who led the College Thriving initiative, was doing her best to shake off the career jitters by getting students to channel their elementary-school ambitions. “What did you want to be when you were in kindergarten?” asked Dopheide, inviting the students to share reflections with one another. “How many of you are still interested in that, or are still pursuing that?”

It was part of an exercise designed to get students thinking about values and life goals and consider how their visions of successful adulthood might evolve over time. One of the oft-noted characteristics of today’s college students is that they enter school with a lot more career concerns than previous generations, worried almost from day one about how coursework and extracurricular activities will translate into rewarding and meaningful work.

Gallup, based on polling back to 2018, found 58 percent of students reported that their primary goal for higher education is to improve job and career prospects. Only about 23 percent reported “a general motivation to learn more and gain knowledge without linking it to work or career aspirations,” according to the survey.

Of course, first-year students are mostly still teenagers, and their conception of career options can be limited. In Dopheide’s class, several students expressed their desire to make good money without burning out, though no one seemed to have a clear idea of what constitutes good money. “I started out wanting to be a lawyer, because I want to be comfortable,” said the young woman with the pink fingernails. “But it’s so stressful! Maybe I need to get a stay-at-home husband,” she mused, to plenty of laughter from her classmates.

Several students expressed consternation with the career advice they’d been offered after completing a third-party online survey that gauged their interests and skills. “There’s a temptation to do the job that would make money, even if you’re not passionate about it,” offered a young man in the back of the room. “But some of these options, it’s like you’d have to pick up two jobs just to stay off food stamps.”

“We really need those moments of discovery,” said Elizabeth Engelhardt, senior associate dean for fine arts and humanities. “We want students to take that one-off course in linguistics, try a language they’ve never explored, take that intro calculus course to see if they want to move into whatever science field interests them.”

He was emphatically not planning to become a summer camp director, as the online planning tool suggested.

The ambient worry about finding a lucrative route through post-graduate life is a challenge for universities such as Carolina, where all undergraduates start out in the College of Arts and Sciences. Broad general education requirements are meant to expose students to an eye-opening range of disciplines and topics before they commit to a major or a professional degree. It’s Carolina’s way of preserving the age-old tradition of forging well-rounded, intellectually curious graduates at a time when students and families feel pressure to focus early on something that will lead to obvious job prospects.

Despite ample data showing that English majors and arts enthusiasts from Carolina make out perfectly well in the long run — surveys from UNC Career Services show about 96 percent of graduates are either employed or in graduate school six months after leaving Carolina — there’s a strong sense among students that they need to study something practical to make the time and expense of college worth it. “We understand the value of a liberal arts education, but we don’t always do a very good job of articulating it,” said Jim White, who became dean of the College of Arts and Sciences last year. “I want us to make sure arts and sciences students understand what they can bring to the job market.”

The IDEAS in Action curriculum addresses this, in part, by explaining the “capacities” that students gain from courses and requirements. Instead of prescribing specific content that students need to cover, the new approach focuses on the skills students can acquire by taking a range of courses. The Making Connections curriculum included requirements such as at least one course each in literature, the North Atlantic World, philosophical analysis, as well as others.

The revised curriculum divvies up requirements by broad academic and life skills, with categories such as Quantitative Reasoning, Aesthetic and Interpretive Analysis, and Engagement With the Human Past. Theoretically, a lot of courses from different disciplines might teach those skills, and thus meet the requirements for general education classes. If students want to knock out their Natural Scientific Investigation capacity — mastering the scientific method and applying it to the natural world — they can complete it by taking a linguistics class, a geology survey on weather and climate, or a physics course on calculus-based mechanics and relativity.

“That’s the neat aspect of the focus capacities,” said Abigail Panter, senior associate dean for undergraduate education. “No academic department owns each one, so they can be met in a variety of disciplines. If you can show you’re going to be meeting these student learning outcomes, your course will be approved for that capacity.”

The curriculum also details learning outcomes and recurring skills in plain English, an attempt to show students how academic work can translate into marketable qualifications. Every general education course includes substantial writing, practice with presentations and public speaking, and collaboration with classmates. “These are all things employers love, of course,” White said. “We’re helping students articulate the things they’re doing in the classroom in a way that’s recognizable beyond Carolina.”

Getting a committee of faculty from across campus to agree on shared learning objectives was not easy to finagle, but leaders from different departments recognized a shared interest in promoting a wider exploration of courses. Some majors at Carolina, such as computer science and business administration, are severely oversubscribed while others languish for lack of interested majors. University officials hope a capacity-driven curriculum will offer a chance for departments struggling with enrollment —such as history, English and others that have suffered from the long-term decline in the traditional humanities — to reach more students.

“We really need those moments of discovery,” said Elizabeth Engelhardt, senior associate dean for fine arts and humanities. “We want students to take that one-off course in linguistics, try a language they’ve never explored, take that intro calculus course to see if they want to move into whatever science field interests them. This curriculum really urges and directs that kind of exploration.”

The most ambitious effort to get students thinking across disciplines are the so-called Triple-I courses (Ideas, Information and Inquiry), which bring together three professors from different fields to study a broad theme from various angles. Death and Dying might bring together three faculty from anthropology, English literature and neuroscience to offer students a wide-ranging examination of how society thinks about mortality. Science for Hyperpartisan Times delves into public policy, communication and the ethics of data analysis, among other subjects.

It’s an extraordinary commitment of resources to have three professors co-teaching a course, and the University is still figuring out how sustainable the model might be. But there’s excitement about how a focus on big issues that cross disciplinary boundaries might lead to more creative energy, not just among students but among faculty.

“How can people from wildly different fields look at the same question, the same sets of data and have very different ways of coming at it?” Engelhardt asked. “You’re in a room thinking about what are the biggest, most exciting questions that these different fields can bring together. We are saying to students, ‘We offer all these different ways into this big question, this provocation, this set of data, and look what happens when you pivot around it!’ That should be a skill that’s really helpful wherever you end up.”

Learning in a 3D world

Before students get to wander into the open range of the course catalog, IDEAS in Action takes a much more prescriptive approach to the first year. There’s the College Thriving course that’s now mandatory for all first-year students, intended to help them meet their academic adviser, define goals and establish healthy habits for living and studying on campus. That course was built into the new curriculum before the coronavirus pandemic hit, and professors say it’s even more vital now because of the learning disruptions that so many incoming students endured when K–12 schools were closed and learning moved online.

“A lot of them find it super hard just to sit in a classroom for 50 minutes, engaged in discussion with sustained focus,” Dopheide said. “We’re helping them relearn how to engage with people in the 3D world, meeting them where they are, given their life experiences. If I had been through what many of them have been through, I’d be grateful for this kind of additional support.”

IDEAS in Action also requires nearly all incoming students to take English 105, now called Writing at the Research University, a composition class that prepares them for the rigors of academic research and writing. For students who arrive at Carolina after demanding high school experiences, the requirement can seem burdensome; a lot of those students used to place out of their introductory English requirement through Advanced Placement credits. But the course helps set clear expectations for how college-level work will differ from basic high school assignments, and that has proven valuable for many students. “I loved that class!” said sophomore Benjamin Kaheel, who graduated high school in Raleigh. “It was basically three big projects, and all the assignments were small subtasks for the projects. So there was no way you could get behind. I got much better at getting organized.”

There’s also a new expectation that all first-year students will take at least one seminar course, allowing them to engage in deep discussions with a faculty member and a small cohort of fellow students. Years of research at Carolina and elsewhere showed the power of small seminar courses to build student confidence and make them feel more connected to the University, but not all students had the opportunity to take the courses. They will now.

Students have four (sometimes five) years to become thoughtful citizens, critical consumers of data and rhetoric, skilled writers and presenters, engaged and aesthetically attuned contributors to arts and culture, scientifically literate and intellectually modest in understanding how knowledge is created. … It’s striking to see how much society asks of universities and the people who pass through them.

“We wanted more commonality of experience, in part out of a desire for fairness,” Engelhardt said. “We tried really hard in places like the first-year seminar to make sure we’re getting our best researchers and scholars in front of students early.”

In a move that has prompted some grumbling among students, the curriculum now requires that they attend a number of extracurricular activities — lectures, performances, exhibits — to get acquainted with all of the richness Carolina offers outside of class. “Everyone has to get out and do things on campus,” Panter said. “We know it’s good for students, and it’s a valuable habit to build.”

High-impact experiences

Carolina’s curriculum writers also zeroed in on other undergraduate experiences that were both highly valuable and unevenly available. These “high-impact experiences” — things such as undergraduate research, study abroad programs and summer internships — play an outsized role in launching graduates into ambitious careers. IDEAS in Action is designed to expand those experiences to more Carolina students.

Tara Hinton, a junior from Sylva, got involved in undergraduate research projects during her earliest days at Carolina. She has worked in a lab studying sea turtles, traveled to a field site on the Outer Banks to conduct interviews on environmental change and delved into the University’s library archives for an Honors Carolina project on the role of enslaved people in UNC history. This summer, she interned at the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center on Harkers Island, conducting oral histories about hurricanes and resilience with local residents.

“I think research is promoted really well in a lot of the science-y classes, but it’s not always the same with the humanities,” Hinton said. “Being involved in research has given me a lot more connections and confidence. I feel like I have people I can go to and places I can start after I graduate.”

She also said the experience of internships and fieldwork have deepened her appreciation for North Carolina, making it more likely she’ll pursue a career in-state after graduation. “I think just seeing how rich and beautiful our state is, both in the natural environment and in the people, has been powerful,” she said.

Panter and her colleagues in campus administration found that low-income and first-generation students were less likely to secure a high-impact experience by the time of graduation because of resource constraints and for lack of familiarity with what’s possible. Requiring courses that include fieldwork, archival research or internship placement is a way to help level the playing field among students.

Beyond Carolina

To the extent students are paying attention to any of this curricular evolution, they mostly experience it as a set of demands. Undergraduates, by and large, do not arrive on campus with strong theories about pedagogy and the University’s intellectual superstructure. “When I went to register, there were so many gen-eds I had to take!” Kaheel recalled, referring to general education requirements. “That’s stressful when you’re looking at all the [requirements] for different majors and wondering how to fit it all in.”

The more prescriptive approach to their early semesters at Carolina has been a regular complaint from some students. For those eager to dive into their preferred majors or begin work on requirements for business school or medical school, the mandatory coursework during their first year can feel burdensome. Sophomore Tejasvani Venkatkumar, one of the students who took Dophiede’s Thrive class as a first-year student, said many of her peers are annoyed at how many general education classes they are required to complete before they can focus on a preferred major. “But I like how it makes it a requirement to explore topics I would not have signed up for otherwise,” she said.

Proponents of IDEAS in Action hope more students will come to appreciate the breadth of experience in the new curriculum. They’re collecting data on what students like, how faculty members think the curriculum is working and how different classroom experiences impact the path to graduation. Everyone expects changes to the curriculum in the years ahead, refining IDEAS until it delivers on the promise of a capable and confident Carolina graduate.

One pending change is already attracting plenty of debate. Among the higher-level requirements set to take effect next year is a course called Communicating Beyond Carolina — COMMBEYOND in bureaucratic shorthand — which is intended to cultivate “careful listening, effective communication and collaboration.” This anodyne concept has become a campus hot button after some Board of Trustees members suggested it was a natural place for a class on civic discourse or debate, pushing students to engage in political dialogue and confront ideas they might disagree with. The COMMBEYOND requirement was mentioned in email exchanges between trustees and Provost Chris Clemens about the proposed School for Civic Life and Leadership, which became contentious after trustees endorsed it and faculty expressed concerns about political meddling in academic decisions.

White has sidestepped the controversy, focusing instead on the substance of the COMMBEYOND requirement and emphasizing civic education has always been important for a public university. A decision about how to introduce it is expected in the coming months, with thousands of students subject to the requirement starting in 2024. “This is basic democracy,” White said. “Democracies require that we listen to each other. You need to learn to listen, to form your own opinion, to understand why you feel that way and why others might feel differently. And you need to do this in a civil way.”

It sounds like a reasonable ask of a public university graduate, alongside the many other demands that IDEAS in Action makes of a new generation of Tar Heels. They have four (sometimes five) years to become thoughtful citizens, critical consumers of data and rhetoric, skilled writers and presenters, engaged and aesthetically attuned contributors to arts and culture, scientifically literate and intellectually modest in understanding how knowledge is created. When it’s all written out in an eight-semester plan, it’s striking to see how much society asks of universities and the people who pass through them.

“There’s just too much pressure across higher education to know what you want out of life when you’re a 19-year-old freshman,” Guskiewicz said. “I hope by the time they reach their last semester here, they can begin to believe and see who they might be. But they still shouldn’t know. They should feel ready for whatever life brings them.”

Eric Johnson ’08 is a writer in Chapel Hill. He works for the UNC System and the College Board.

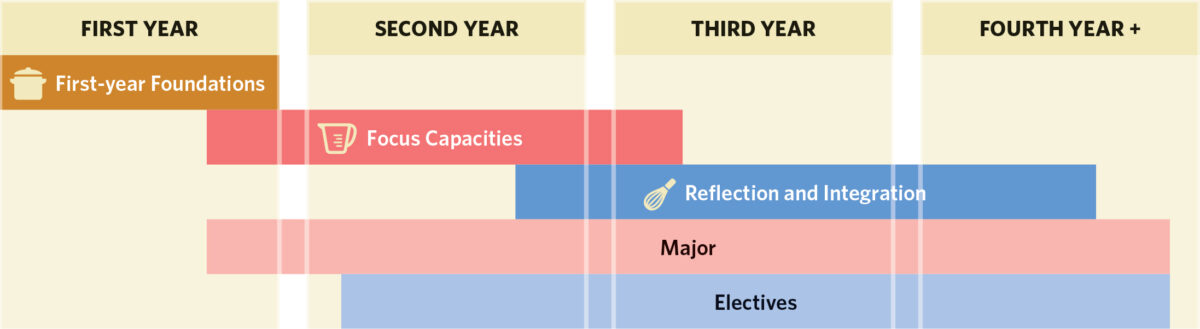

IDEAS in Action is composed of three elements: First-year Foundations help students transition to college; Focus Capacities provide opportunities to write, collaborate and present material; and Reflection and Integration call for students to put capacities into practice.

First Year Foundations

- College Thriving: Covers a range of topics including science-based strategies for effective learning, engaging with the campus community, self-care and wellness, such as mastery of basic mental health, drug and alcohol, and sexual wellness practices. Example coursework: Pass/fail course meets weekly in a small class environment

- First-Year Seminars and Launches: Incoming first-year students with no prior college experience engage with peers and instructors to learn how scholars pose problems, discover truths, resolve controversies and evaluate knowledge. Example seminar: What is Critical Race Theory? (American Studies)

- Triple–I: Ideas, Information and Inquiry: Brings together three professors from different departments so students can study a common theme from several perspectives. Example course: Science for Hyperpartisan Times (Interdisciplinary Studies)

- Writing at the Research University: Introduces students to academic writing across the disciplines of natural sciences, social sciences or business, and humanities. Example course: English Composition and Rhetoric (English)

- Global Language: Students consider the nature and structure of their native language and reflect upon their own cultural norms while gaining functional linguistic proficiency in the language of study, as well as an appreciation of the cultures and worldviews represented. Example course: Intermediate German (German)

Focus Capacities

- Aesthetic and Interpretive Analysis: Literary and artistic works allow students to step into another’s experience and broaden awareness to their realities, struggles and accomplishments. Example course: Gender and Popular Culture (Women’s and Gender Studies)

- Creative Expression, Practice, and Production: Students engage in a range of experiences to learn new techniques, use multimedia tools and create products that reflect their viewpoints and align with their interests. Example course: Photography I (Studio Arts)

- Engagement with the Human Past: Learn and evaluate how events shaping the world today have been shaped by events of the past, and how to identify the patterns of human history that shape our lives. Example course: Ancient Cities (Classical Archaeology)

- Ethical and Civic Values: Learn how different perspectives can influence our idea of what is ethical and how to think critically about how we make and justify private and public decisions and evaluate the actions of public leaders. Example course: Information and Computer Ethics (Information and Library Science)

- Global Understanding and Engagement: Analyze diverse historical, social and political exchanges that shape nations, regions and traditions. Example course: Global Christianity (Religious Studies)

- Natural Scientific Investigation: Learn how to make and test hypotheses, collect and interpret data, and communicate and defend your conclusions. Examine the rules that govern science and test the limits of our ability to investigate them. Example course: Weather and Climate (Geography)

- Power, Difference, and Inequality: Students engage with the histories, perspectives, politics, intellectual traditions, and/or expressive cultures of populations and communities that have historically been disempowered, and the structural and historical processes by which that disempowerment has endured and changed. Example course: Language and Power (Anthropology)

- Quantitative Reasoning: Understand and apply mathematical concepts in real-world situations and develop methods for using data, logic and math beyond the textbooks and equations. Example course: From “The Sound of Music” to “The Perfect Storm” (Marine Science)

- Ways of Knowing: Students explore a concept from a variety of perspectives, which will reveal patterns of thought that they may not be aware exist and tackle new experiences that teach them how to become more aware of themselves and their beliefs. Example course: Cities and Urban Life (City and Regional Planning)

- Empirical Investigation Lab: Advancements in science have made significant breakthroughs over time. Learning approaches to empirical investigation (measurement, data collection and analysis, hypothesis testing) is necessary so students have the ability to inform their communities and influence the world. Example course: Human Language and Animal Communication Systems (Linguistics)

Reflection and Integration

- Research and Discovery: Courses allow students to immerse themselves in a research project, incorporating reflection and revision to produce and disseminate original scholarship or creative work. Example course: Seafood Forensics (Biology)

- High-Impact Experience: Includes public service, study abroad, internships, performance creation or production, undergraduate learning assistant or other teaching experiences, and collaborative online international learning. Example course: Air and Space Expeditionary Training (Aerospace Studies)

- Lifetime Fitness: In this course, students practice a physical activity or sport, learn about health and well-being and have fun. Example course: Yoga and Pilates (Lifetime Fitness)

- Communication Beyond Carolina: Students learn how to persuasively convey knowledge, ideas and information to a variety of audiences across different mediums, for example, digital, oral, written. Example course: Public Speaking (Communications Studies)

- Campus Life Experience: Students experience the artistic, intellectual and political life of UNC and connect them with their academic work. Example work: Attend and interpret campus performances, lectures and events

SOURCE: UNC IDEAS IN ACTION WEBSITE

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.